Project October 30, 2012

Along the Burma Road: Soft Power and Piracy

Country:

On the morning of October 5, 2011, two Chinese barges bearing loads of apples, garlic, and some $1.5 million of methamphetamine drifted slowly down the Mekong River into the Golden Triangle to run drugs, gamble, and kill off unwanted ethnic minorities. As they passed the Sam Puu—the island redoubt of the "freshwater pirate" Naw Kham—the crew gathered on deck. Soon they heard the throaty growl of speedboats coming from somewhere out in the mist. First one, then another, then a third brightly painted boat came into view. As they hove to, the men in the boats fired their guns into the air and motioned for the barges to cut their engines.

What happened next depends on who you believe. In April 2012 Naw Kham, the notorious "freshwater pirate" of the upper Mekong, was arrested in Laos and extradited to China for the murders of the Chinese crews. Prominent Thai politicians have publicly charged a "rogue" Thai paramilitary unit with the massacre. The truth, if it ever comes out, will reveal much about the shifting geopolitics of the Golden Triangle, the notoriously lawless region of the Mekong where Laos, Burma, China, and Thailand all meet.

The Golden Triangle has changed a lot since its heyday as the cradle of the world's opium trade. The Chinese alone account for over 1 million tons of shipping along the Mekong. And that figure doesn't include the vast trade in illicit goods. The renewed drug trade has allowed the ethnic militias within the Burmese side of the Golden Triangle to continue funding its civil wars with the ruling junta. It is also funding a growing backlash to the heavy hand China employs in the region. As the volume and value of both licit and illicit trade have increased, so have the incentives for pirates like Naw Kham—a shadowy figure tied to the Shan ethnic militia—to extort a portion of the lucrative trade. Elements within the Thai and Burmese governments are widely believed to be complicit in the rampant river piracy, and the local population has hailed Naw Kham as a hero for standing up to the regional hegemon.

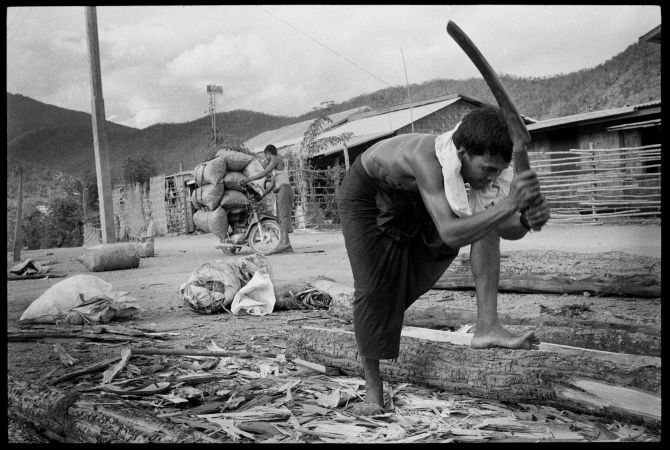

In July 2012, journalists Jeff Howe and Gary Knight traveled to Southeast Asia to report on the rapidly shifting geopolitics of Southeast Asia. One component of the trip entailed reporting on the Mekong killings, both in Bangkok and in the Golden Triangle. But another component took a broader tack: Analyze the pervasive influence of China, not only in the shipping along the Mekong, but in the soft power it exercised in countries such as Burma, also known as Myanmar.

To that end the pair traveled to Mandalay, where they began a journey along the Burma Road–first built by British and Chinese to keep Chiang Kai shek's forces supplied as they battled the Japanese. This effort failed; not long after bombing Pearl Harbor the Japanese invaded Burma in one of the most destructive campaigns of the war. The British and the Japanese are long gone now, but Burma now serves as a different kind of crossroads, where Chinese, Indian, and increasingly, Western governments and businesses jockey for diplomatic and economic influence. Burma is in possession of both strategic geography—offering China access to the Indian Ocean and a chance to bypass the troubled Malacca Straits by which 80 percent of its imported oil now passes—and riches in the form of rare minerals, natural gas, and oil.

-

×

English

English