One of the favorite cooking spots at Rusila Posala’s house has always been under the mango tree in the backyard.

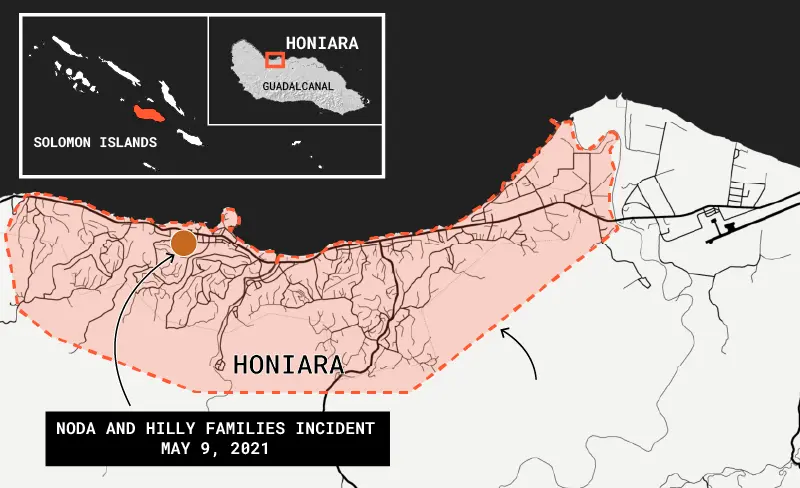

So it was the place that, on May 9, 2021, parishioners from the Seventh Day Adventist Church congregated to cook the meals they would deliver throughout the Solomon Islands capital of Honiara as part of a Mother’s Day fundraising event. The money would go to the church’s youth group, in need of a PA system for its community events. It was a pretty typical Sunday for the churchgoers.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Maeverlyn Pitanoe, 50, finished up the last of the cooking—some cabbage—at the base of the tree. Posala’s nephew Raziv Hilly and Charles Noda, another friend, held out their plates.

Something below the fire started hissing.

Then, the U.S.-made 105mm projectile that had been in the ground since the 1940s blew up.

Shrapnel ripped through the three churchgoers, and continued on, slamming into other people dozens of feet away.

Charles, 39, suffered a yawning, bone-baring wound on his thigh. Some of Maeverlyn’s fingers were severed, her arms streaked with gaping wounds. The 29-year-old Raziv’s legs were cut off at the knees, a piece of metal driven into his back.

The people of Honiara know it’s futile to call for an ambulance. So the churchgoers rallied, fashioning tourniquets of rags and clothing. They loaded the badly wounded trio into a convoy of private vehicles and raced through the heart of the city to the National Referral Hospital.

Raziv died shortly after 3 p.m. His family said he prayed all the way to the hospital. Charles died a week later of sepsis—blood poisoning.

These were not subsistence farmers from rural outposts who died that day in the hills above the country’s largest city. The bombs are killing citizens from all walks of life and across the islands.

Raziv was a civil engineer with the Ministry of Communication and Aviation, a leader in his church’s youth group. Charles was a father of four and an accountant in Honiara.

They were both from well-connected, well-to-do families in the Solomon Islands. They’d earned degrees at colleges overseas and had flourishing careers. Both were leaders in their church and potentially, many attest, of the country.

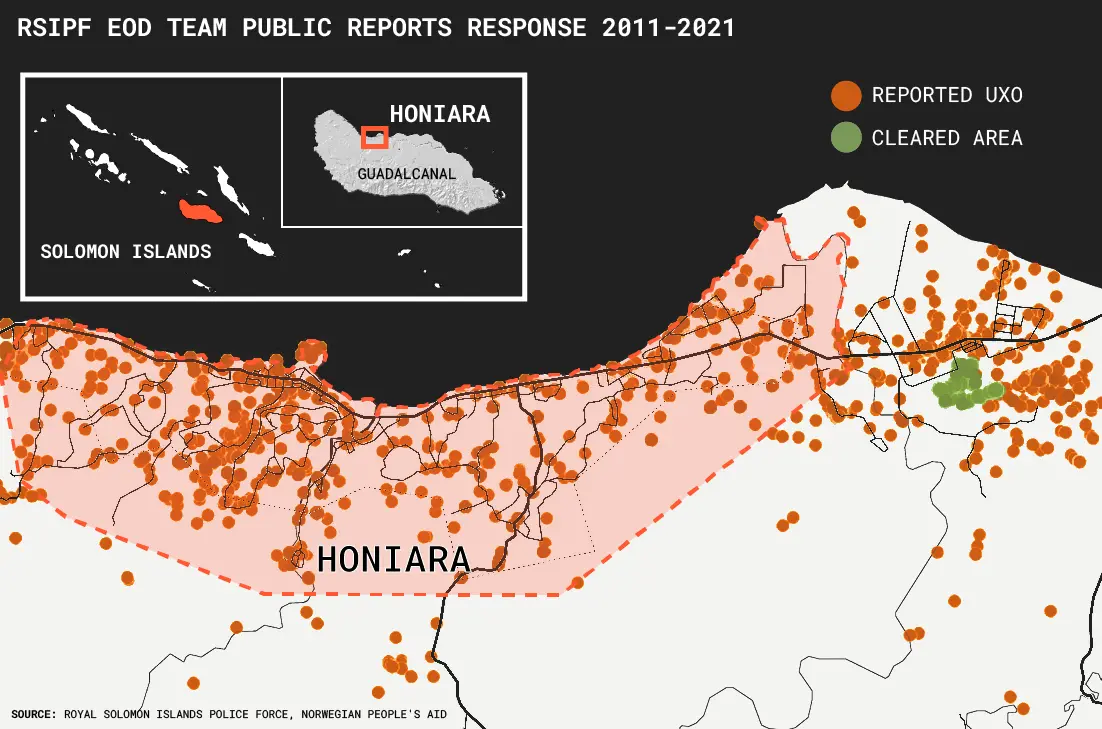

Their deaths and the deaths of at least four others last year have served as a wake-up call to people in the islands where researchers estimate more than 20 Solomon Islanders are killed every year by World War II-era unexploded ordnance as they fish, farm or cook over an open fire.

In the sprawling South Pacific archipelago, experts say what may add up to millions of pounds of bombs and other deadly devices were simply abandoned by the Japanese, the Americans and their Allies when the war ended nearly 80 years ago.

Now, people are finally acknowledging that no one is safe, and that the country needs help—both financial and technical—to find and remove the massive amount of leftover UXO.

The first step, by all accounts, is a long-needed survey of where the bombs are. Most of them lie unseen a few feet beneath the surface. But, as happened to the Honiara church group, they are beginning to emerge as weather and other environmental factors slowly uncover them.

Australian, Japanese and U.S. diplomats in Honiara are quick to assure Solomon Islanders and journalists that clean up is a priority that will be shared among them all. They meet regularly to discuss the issue but insist that systematic removal can’t begin until a survey provides an understanding of the scope and cost to find and destroy the explosives strewn throughout the country.

The U.S. actually started a survey in 2019 but it was cut short when two of the survey leaders were killed by WWII explosives in a Honiara apartment. The surveyors, with the humanitarian organization Norwegian People’s Aid, which specializes in demining, died when an explosive they were tinkering with in their apartment blew up.

The Solomon Islands government stopped the project and any work that was being done on UXO removal outside of the government police bomb squad’s day-to-day responses.

With the survey on hold, other UXO efforts in the Solomons also faltered. One of those was a two-phase program conducted by Japan, which was intended to complement American efforts, focused on equipment, education and infrastructure.

“Our goal is the same, to take all of the UXO out of this country,” says Yoshida Norimasa of the Japanese Embassy in Honiara. “People say it’s not realistic, it’s too many UXOs.”

Once the survey is complete, the U.S., Japanese, Australian and Solomon Islands governments intend to target the most populated areas first, Norimasa says. Then the effort will extend outward.

Norimasa says Japan may also consider building a facility much like the police bomb containment compound known as Hells Point in Munda, in Western Province. Earlier this year, Japan donated two new pickups and other equipment to the police explosive ordnance disposal team that is headquartered there.

Last year, Australia announced a $10 million package that includes a specialized excavator, further training to international standards and an upgrade of Hells Point.

Still, the question remains why it has taken so many decades for the countries that left the bombs behind to come back and clean up their mess.

Norimasa offers little in the way of explanation saying, simply, “It’s so regrettable that we couldn’t do anything for so long.”

U.S. officials are quick to point out that aid is delivered at the request of governments. It’s only been in the past 10 years that the Solomon Islands began asking for help. Solomons officials acknowledge they didn’t really know how to go about it.

For the U.S., those requests are typically filtered to the State Department’s Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement, under the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs.

Geary Cox, OWRA’s manager for the South Pacific, says work done in 2010, by the Office’s Quick Reaction Force, which deploys around the world, seemed to create greater awareness throughout the Pacific. That’s when some money started flowing into the country.

“Why did assistance not come earlier? Well, we hadn’t received a request,” Cox says.

But while tens of millions of dollars in congressional funding for UXO removal has been directed to countries such as Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, money for the Solomon Islands has been piecemeal and no Pacific nation has been specifically targeted.

More recently, the U.S. has renewed discussions with the Solomon Islands police about the national survey and the process is expected to resume in 2023.

The U.S. has agreed to spend $1 million for another contractor to perform the survey, but it has yet to award the contract. Proposals were due in September.

The request for proposals on file with the State Department’s OWRA includes restarting and completing the survey as well as providing more advanced training to the Solomon Islands bomb squad and providing storage sites for bombs at police stations around the country. Generally, the work seeks to boost regional security, civilian security and “promote U.S. foreign policy interests.”

Cox says the underlying goal of the likely “multi-year, multi-million dollar” contract is to not only find and document UXOs throughout the islands but also empower the local police bomb disposal team to continue its work.

“The Solomon Islands EOD teams are a model for how national capacity can continue to be available to address these issues,” Cox says. “The next phase in growing that capacity is to talk about systematically understanding it and then addressing it.”

Cox says given the “good relationship” that has been fostered between the U.S. and Solomons, it’s more a question of when, not how, a long-term solution comes about.

“I think that we are interested in a long-term investment and solution to the problem,” Cox says.

Golden West Humanitarian Foundation is vying for the contract, along with several others, including the Halo Trust, a British-American nonprofit focused on clearing several former war zones across the world.

As Halo’s Head of Programme Development, Simon Conway travels around the world scoping former war zones for the organization’s work. In August, Conway spent two weeks in the Solomon Islands to get a better understanding of the country’s problem.

Conway is former co-chair of the Cluster Munitions Coalition, which successfully campaigned for the implementation of a treaty banning the use, sale and production of cluster bombs in 2008, called the Oslo Convention.

Until now, the Solomon Islands has barely figured in conversations on the international stage, Conway says.

“Frankly, I was shocked by the level of contamination,” Conway says, as well as the similarities to other former battlegrounds. “People have been living in close proximity for a very long time—they don’t plant plants with deep roots, they don’t build fire pits too deep.”

Experts say that any long-term solution for the Solomon Islands, a collection of nearly 1,000 separate islands, will require significant coordination by any organization that joins the Solomon Islands bomb squad in removal and disposal.

The Australian NGO SafeGround, a co-recipient of the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize as part of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, believes having a centralized hub of bomb disposal technicians, which includes international surveying and disposal outfits, is the best option.

The NGO’s co-founders John Rodsted and Mette Eliseussen have worked around the world and have spent almost a decade advocating for the Solomon Islands.

“It’s too big for one operator,” Rodsted says. “Someone could go to New Georgia (island), someone could go to the Shortland Islands—get really stuck into this stuff and really fix the problem.”

WWII’s Legacy: Prosperity?

The plan to re-start the survey is encouraging to many in the Solomon Islands and their allies in the NGOs that work to clear land mines and explosives from former war zones.

But it still seems to be low on the U.S. priority list for the Pacific region. Instead, top U.S. officials seem most intent on devising and funding programs that keep China from gaining a political and military foothold in the region that the U.S. has long considered its own strategic turf.

When the Allies and Japan met in Honiara earlier this year to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the U.S. landings in the Solomon Islands, little was said publicly about the deadly legacy of UXOs that are spread throughout the islands.

In August, Hawaii Congressman Ed Case commemorated the war through a resolution that lauded the U.S. effort in World War II and the fact that “the Solomon Islands and Japan and the broader Indo-Pacific have lived and prospered under 3 generations of democracy.”

The resolution made no mention of the leftover ordnance. Nor did it recognize that, in fact, the Solomon Islands is the second poorest nation in the Pacific and has faced political instability since gaining independence from the U.K. in 1978.

Its health care system is inadequate. The government is unable to provide reliable services like water, sanitation and education, along with other basic human needs.

In an interview, Case says the country’s “prosperity” is still better than what it would have been if the U.S. hadn’t taken it from Japan in WWII.

That doesn’t mean the Solomon Islands is where it should be, he adds.

The U.S. has neglected its relationship with the Solomon Islands for decades, he says. It never established a U.S. embassy there and in 2000 pulled its Peace Corps presence, leaving Solomon Islanders with little U.S. aid.

“I think we deserve criticism for not being fully engaged in the Pacific, in particular,” Case says.

In 2019, Case and other members of Congress created the Pacific Islands Caucus to try to address the U.S.’s waning presence in the Pacific and to increase long-term sustained engagement in the region.

In 2021, the caucus supported the Blue Pacific Act, introduced by Case, which would direct $149 million a year through fiscal year 2026 toward climate change and resilience, press freedom, public health and education, among other things.

The measure hasn’t passed, but Case says some of that money could go to provide assistance in the area of UXO.

“We do assist countries with their UXO. I’m not going to sit here and say that that’s at the level that it should be,” Case says, adding that the responsibility belongs to Japan and other countries involved in the war in the Solomons, not just the U.S.

But with China continuing to make diplomatic inroads throughout the region, Case’s resolution landed at a time of geopolitical uncertainty for America. U.S. concerns came to a head in May, when the Solomon Islands signed a security pact with China.

Case says the Solomons’ “path towards an alliance with China” isn’t fair and doesn’t recognize the sacrifices America made three generations ago.

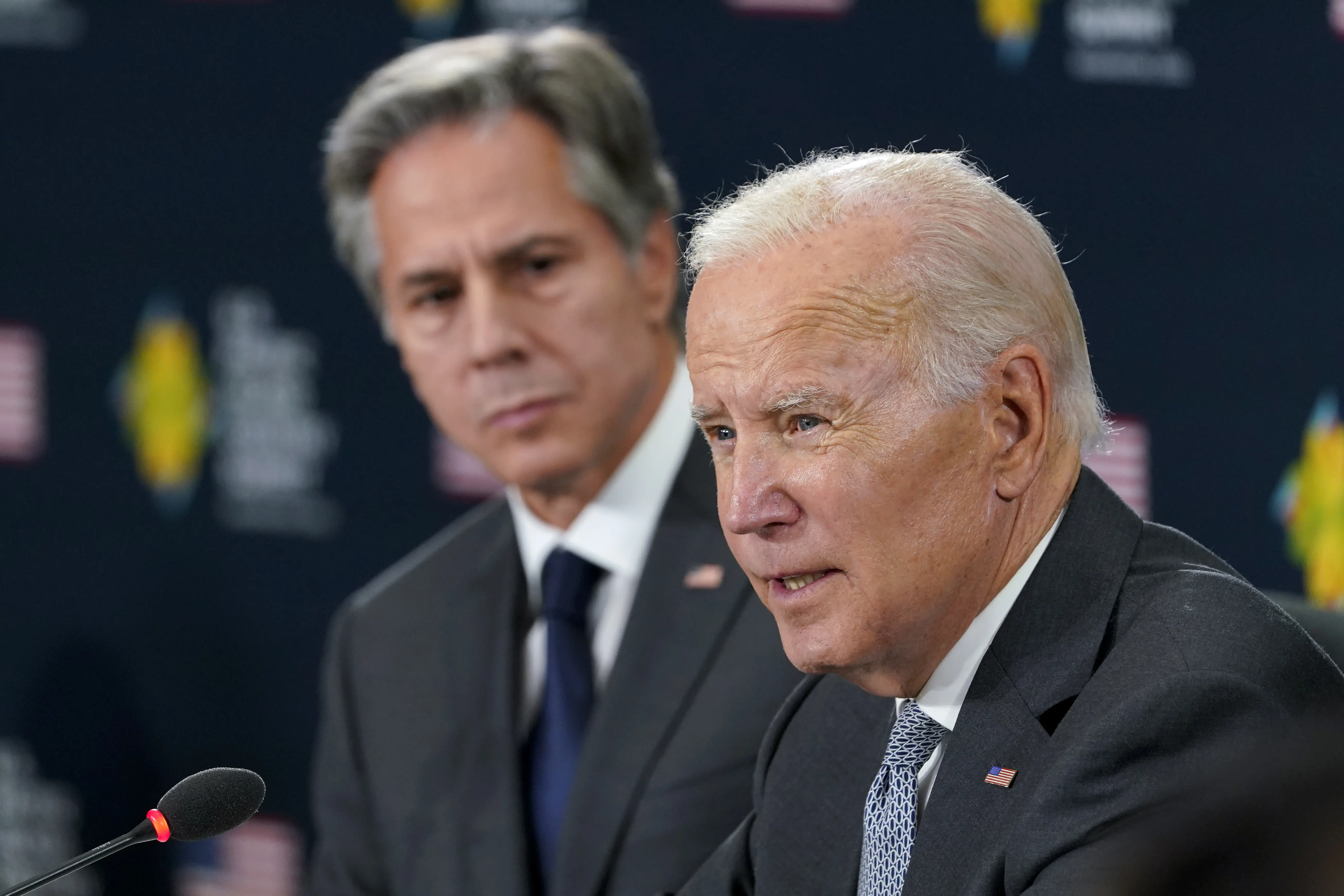

The White House has launched a charm offensive in response, hosting a Pacific Leaders Summit in Washington, D.C., in late September, where President Joe Biden announced the first-ever Pacific Partnership Strategy, which came with $800 million in commitments. In an accompanying 16-page strategy, a single, vague bullet point mentions the U.S. commitment to “war legacies.”

The most sustainable response, according to former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, is to ensure the Department of Defense mandates UXO recovery and remediation in its budget because the defense budget fluctuates and its priorities shift as political pressure changes.

“The fact is there are generations of people, particularly in our country, that have no idea about the kind of battles that were fought in the Pacific during WWII,” Panetta says. “Therefore it’s hard for them to (understand) why the U.S. should have a responsibility to clean up a battlefield that was necessitated by the Japanese attacking us at Pearl Harbor.”

No Data On Victims

In the Solomon Islands, victims and their families are desperate for help. Not only are they losing loved ones, they are also losing breadwinners, key members of their families whose loss compromises the entire family’s well-being.

Miriam Noda watched her husband Charles die in National Referral Hospital a week after the blast at the church.

She fled Honiara with her four children, to her home village on Malaita, 70 miles from Guadalcanal. Now, she sells popsicles, grows her own food and lives off her late husband’s pension to get by.

Meanwhile, in Honiara, Raziv’s family still has questions. It wants to see action, some form of help or public recognition, in lieu of money.

Raziv was Alicia Kenilorea’s brother. Her father-in-law, Sir Peter Kenilorea, was the country’s first prime minister. Her brother-in-law an influential member of parliament. Despite her family’s political connections, it is no easier to get help in the aftermath of a UXO tragedy.

Kenilorea says the Solomon Islands government needs to be an advocate for its citizens. It needs to stand up for them and be more proactive in helping to end the problem, she says.

International conventions and organizations exist to specifically address issues similar to the Solomon Islands’ UXO problem. But the Solomon's government has not had the wherewithal to take advantage of those opportunities.

Rusila Posala

Raziv Hilly's aunt

Alicia Kenilorea

Raziv Hilly's sister

Victim assistance is one of the key elements of the international treaties that seek to deal with UXOs and land mines. Re-engaging with the annual mine action conversations in Geneva could help the Solomon Islands, possibly even opening the door to victim assistance funding and programs that exist throughout the world.

None of the governments responsible for leaving the deadly ordnance behind offers any kind of medical or financial assistance to the Solomon Islands victims. Private help is sometimes available for a fortunate few, like Isiah Tengata and his son Senri, whose case caught the attention of private medical professionals and an international civic organization.

The U.S. Congress does appropriate money for victims of UXO, but not in the Solomons. The Senate Appropriations Committee has set aside $85 million for Laos, which stipulates monies be allocated to victims. It also specifies that $30 million be set aside in Vietnam to assist victims of UXO and Agent Orange.

A treaty signed in 1991 between the U.S. and the Solomon Islands might have been able to help victims in the islands, with a direct provision for “just and reasonable compensation” claims from victims of acts or omissions by U.S. forces.

The Solomon Islands never adopted laws to take advantage of the treaty, so it is an ineffectual agreement, according to Solomon Islands lawyer Joseph Foukona, who is also a University of Hawaii history professor. It was signed at a time of political tension, a period when the prime minister dismissed several members of his cabinet and the country’s economy was suffering.

For now, Solomon Islanders and their advocates are banking on the U.S.-funded survey to create a new awareness and subsequent action based on more reliable data collection. The islands’ police agency and public health system would be able to get a more complete picture of the situation, rather than treating UXO death or injury like a freak accident.

“And that’s always very often taken as if there is no victims, there are no accidents, and that is not the case,” says Mette Eliseussen of SafeGround, which has worked extensively in the Solomon Islands and knows the situation as well as anyone.

“It’s really important to start documenting the victims […] but also see what we can do to help them.”