Citizens in the Pacific nation are growing frustrated with continued deaths and injuries. But government officials point to more pressing needs and political turmoil.

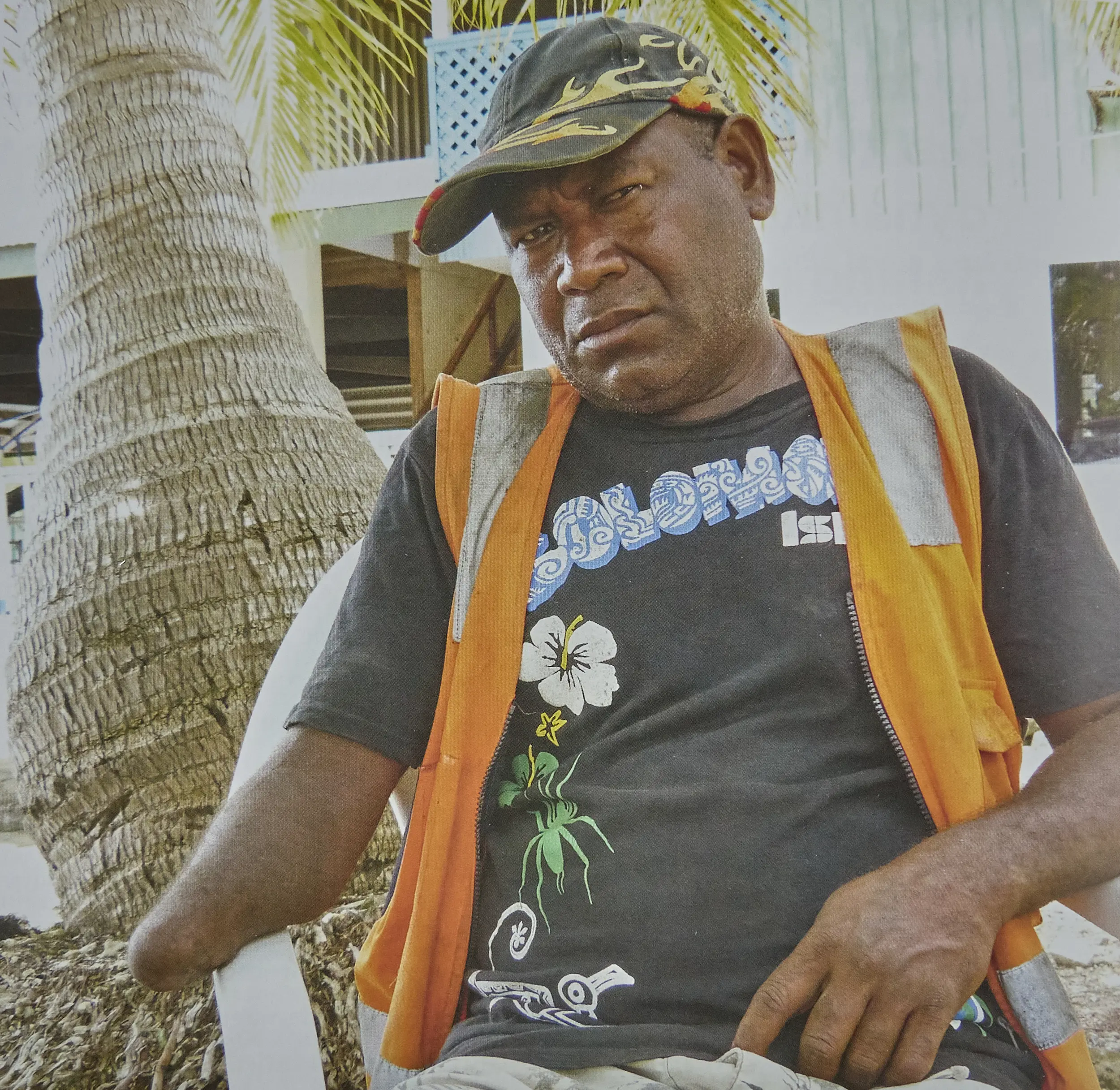

Isaiah Tengata frequently reminded his children to steer clear of the rusting bombshells littering their neighborhood atop a ridge on the outskirts of Honiara.

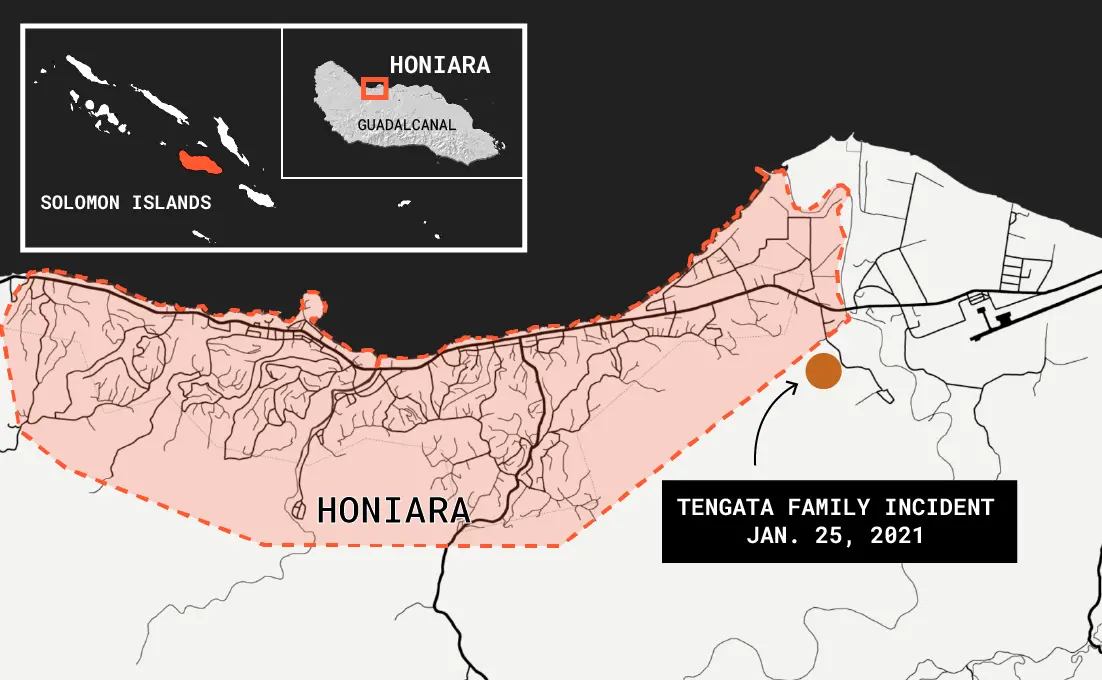

But after school on Jan. 25, 2021, his bright and spirited 11-year-old son Senri ignored his father’s warnings. Senri and his friends noticed what turned out to be a cache of 28 American 81mm mortars while playing in a boggy basin, 100 yards from the Tengata home. The dart-shaped World War II projectiles were apparently unearthed during the previous weeks’ rains.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Senri says his friends begged him to leave them alone. But he grabbed one. The muck-covered insides fell from a hole in the bomb that previously had been plugged by dirt. It was white phosphorus, akin to napalm, known for the horrific wounds it causes.

Before Senri could stop it, the putrid chemicals flowed over his hand and arms, smoking as they ate through layers of skin.

A neighbor found Senri and stripped off his burning clothes, then carried the howling boy home to his father. Isaiah bundled Senri into his cousin’s car and they sped to the hospital.

His father still recalls the drive and his son’s smoking skin. Senri remembers the pain, so anguishing that it’s no wonder white phosphorus is restricted under international laws.

Now, Senri’s arms are scarred from his elbows to his fingertips. His left hand is permanently clenched in a fist, his fingers fused together.

The once-lively boy is now quiet, and he gazes into the distance when speaking with a reporter.

Bombs and other remnants of WWII have become a part of everyday life, buried in the landscape and absorbed into reefs. Fishermen have learned to extract explosives to increase their catch. Children scour the jungle for helmets to wear and tanks to play on. Locals scavenge metal from shipwrecks and downed airplanes. War buffs curate WWII museums to make money from visiting veterans and tourists.

In the year following Senri’s accident, at least six Solomon Islanders were killed by WWII bombs. Countless more were injured.

The rash of explosions within less than a year has prompted islanders to call for the U.S. and Japan to finally clear the South Pacific nation of unexploded ordnance that was left behind nearly 80 years ago.

But the Solomon Islands government has also failed to effectively deal with the bombs that are strewn across large sections of the country. It’s one of the poorest nations in the Pacific and Solomons’ officials acknowledge they have never really understood how to work with international treaty organizations that might be of some help. And the government officials don’t have any idea how much UXO is present or even where it is; no surveys have been done and no records have been kept.

The country has faced many challenges since it gained independence from Britain in 1978. The government is unstable, its leaders change frequently.

But the UXO problem is finally starting to get some attention, thanks in part to nongovernmental organizations that are advocating for more help for the country and its citizens.

Setting A Standard

Four years ago, the Solomon Islands government put in place a comprehensive UXO policy, drafted to ensure the safety of its citizens, reduce the bombs’ impacts on the environment and minimize the socio-economic impacts that they bring.

A 36-point action plan called for government representation at international meetings related to land mines, cluster munitions and conventional weapons. The Solomon Islands would also start regularly sending reports to the treaty organizations, something other countries had been doing for decades.

The new policy also required the development of national UXO standards, to oversee the search and disposition of bombs throughout the country.

But little progress has been made on the action plan. International consultants who had been helping with the plan were caught by the coronavirus pandemic and couldn’t return to the islands to help finalize it.

Personnel and funding has been lacking for many items, says Karen Galokale, permanent secretary for the Ministry of Police, National Security and Correctional Services, which coordinates the policy.

The reality is that the Solomon Islands has bigger problems than the deaths of 20 people a year from unexploded ordnance. It’s easy to continue ignoring a situation that’s been going on for decades when health care, education, social services, domestic violence and even corruption are more immediate concerns.

Long-time politician Silas Tausinga, of Western Province, resigned from his political party at the end of last year because he didn’t trust Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, who’s also the leader of the ruling Our Party. In recent months, the government has faced accusations of corruption.

Tausinga, now back in his hometown of Munda, is critical of his colleagues and the political system, as well as their constituents. Votes are bought, politicians are rarely present in their constituencies and corruption is part of the everyday life of a politician, he says.

Still, Tausinga says UXO is not a trivial concern.

Tausinga has grown up with the bombs. They are stacked at the foot of trees, buried in the sandy isles around Munda and they sit in dumpsites on the ocean floor.

“Let me put it this way: I want the people who dropped them to come back and pick them up again,” Tausinga says. “Take them home or take them somewhere that’s not dangerous to our people.”

Besides grappling with significant social issues, the Solomon Islands is also being courted by China, which is trying to get a foothold in the Pacific through diplomatic overtures.

University of Hawaii history professor Joseph Foukona, who’s from the Solomon Islands, says Solomon Islands officials have been intent on the China-backed 2023 Pacific Games — a multi-sport event held every four years in Oceania — as well as debating whether the 2023 national elections should be delayed until 2024.

“They’re more focused on gaining political capital,” Foukona says. “Their focus is more on the games and elections.”

Absorbing The Legacy Of War

Tarcisius Kabutaulaka spent much of his childhood in Honiara, surrounded by the relics of World War II.

The University of Hawaii professor is from Guadalcanal’s southern coast but attended boarding school on the border of Hells Point, an old munitions depot next to Honiara International Airport.

Kabutaulaka remembers explosions coming from Hells Point. He could hear them from his classroom, a repurposed Quonset hut built by the U.S. Marines. He and his schoolmates would search the forest for guava, helmets and military regalia. They watched John Wayne films left by the U.S. servicemen.

WWII airstrips became domestic airports, Quonset huts became classrooms — everything was put to use, including unexploded ordnance. Bombs became makeshift fireworks, trophies, even a tool for fishing.

Kabutaulaka’s Boy Scout troop helped Japanese officials find the remains of soldiers killed in battle, around Honiara, but everything else — bombs included — remained.

Kabutaulaka says Solomon Islanders never really knew there was a way to solve the issue of bombs littering their country.

“I’m not sure people accepted it, but they simply came to assume that nothing can be done about it,” says Kabutaulaka, the former head of the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at the University of Hawaii.

“When they realized that there’s something that can be done about it, then it became a problem.”

Fishing With Dynamite

The issue of UXO is perhaps most apparent in the Solomon Islands when it comes to fishing, which provides one of the main food sources in the island nation.

Solomon Islanders discovered soon after the war that the most efficient fishing tackle is old bombs and munitions.

“Dynamite fishing” was outlawed in 1972 but remains a common practice throughout the nation, difficult to regulate when people are spread across hundreds of islands and police presence is limited.

An estimated 500 fishermen regularly search for UXOs, which they saw open and take out the material inside. They fashion explosives out of plastic bottles, light a fuse and throw them in the water.

But the old weapons of World War II sometimes hold chemicals like mustard gas or white phosphorous.

Too often, someone dies. Sometimes they lose a hand or an arm or are seriously burned.

Just last year, two men were killed on Christmas day, while harvesting explosives in the off-limits area of Hells Point.

But the pay off can be too lucrative to resist. One bomb can bring in a catch worth about $240. The average Solomon Islander earns less than $2,400 per year.

The best market is for reef fish, so most dynamite fishermen target the reefs that surround the islands. But the use of explosives in the sensitive environment raises serious concerns for the near-shore ecosystems in the country, home to the second-most diverse population of coral species.

Dynamite fishing is dangerous and illegal but it continues because it ensures a sizable catch and profit, says Melchior Mataki, permanent secretary to the Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management and Meteorology.

Perpetrators risk three years imprisonment and $120 fine under the fisheries act.

But many fishermen have another strong motive: desperation.

Lush But Killer Land

While fishing is crucial to the country’s food supply, farming is even more prevalent. About 80% of the people in the Solomon Islands rely on agriculture to survive. That puts much of the population at risk of encountering an unexploded munition as they work the land in the vast rural areas, far from any medical help.

Farmer, businessman and political leader John Kwaita has 2.5 acres between Edson’s Ridge and the airport. The lush landscape is good for crops like sweet potato, cassava, taro and yams, as well as fruit and other vegetables.

“It’s good farmland … You have the ridges, then you have the rich valleys, which run down from the mountains,” Kwaita says. “It’s very nice and green. But it’s very dangerous.”

That’s because farmers slash and burn: They tear down existing greenery, burn the detritus, then plant. But open fires — commonplace in agriculture and cooking — are problematic.

When the community leader and his team first cleared his land, they burned the remains in a bonfire. It exploded, sending shrapnel hundreds of yards. Luckily no one was hurt, he says.

Stories of people hoeing their gardens and striking bombs are common. Kwaita now urges community members to light their fires at night, when people are not around, and keep tilling the land, but only a foot deep.

Kwaita grew up on his native island of Malaita, where he was surrounded by remnants of war, though he cannot recall any death or injury resulting from them.

But over the past two years, it’s been different.

“All of a sudden, it feels like they’re coming up to the surface,” Kwaita says. “And it doesn’t take much effort to strike one.”

Kwaita is president of the opposition United Party, started by the country’s first prime minister, and wants his community to act as a model for the rest of the country. He is in the process of implementing programs that address health issues and domestic violence, mainly through education. UXO is part of that.

As a developing nation, the Solomon Islands has many problems that aid organizations already help to address. But not when it comes to the bombs.

“You can build airports and you can build roads. You can do whatever. But it doesn’t fix this. This is something we have to live with — and the next generation,” Kwaita says. “No one should blame anyone for the war. What’s done cannot be undone. We just have to deal with ‘now.’”

Building, With Bombs Everywhere

Not too far from the Tengata family’s home, Michael Macca and a team of private explosive ordnance technicians scan a local parish’s land, next to the Mataniko River, as children return home from school.

Macca was asked to survey the land before the parish builds a house. Safety concerns have been renewed since at least six people died last year when old munitions exploded.

He’s doing it for free, as a favor to the church. But it’s also good training for his new operators.

The crew draws lines with string to create one-meter lanes on the 50-square-foot clearing, before an operator walks up and down between them. The operator scans the area with an imported German metal detector. Another follows behind, spraying paint where the detector croaks to life. Some wear Kevlar jackets, others don high-visibility vests.

Once the grounds are marked, they begin to dig.

Macca started his company, Safe Signals, in 2018, after 18 years with the police bomb squad. In those four years, he has located 366 projectile explosives from around Honiara and about 6,000 bullets. Grenades and mortars are the most common explosives he’s found.

“They’re sort of a regular UXO here in the Solomon Islands,” Macca says, noting about 100 grenades have been recovered.

Safe Signals is not allowed to dispose of the bombs. The already-busy police bomb squad is the only entity in the country allowed to do that.

Equipment has been a massive investment for Macca. His two metal detectors cost more than $43,000. But they are needed to find explosives of all types and sizes that could be up to 24 feet below the surface.

The company charges approximately $1.20 per square meter for businesses and government ministries and $0.23 per square meter for private residences.

“It might be cheap enough for a business house or those who have the money,” Macca says. “For normal farmers and people in the Solomon Islands, it’s still too expensive for them.”

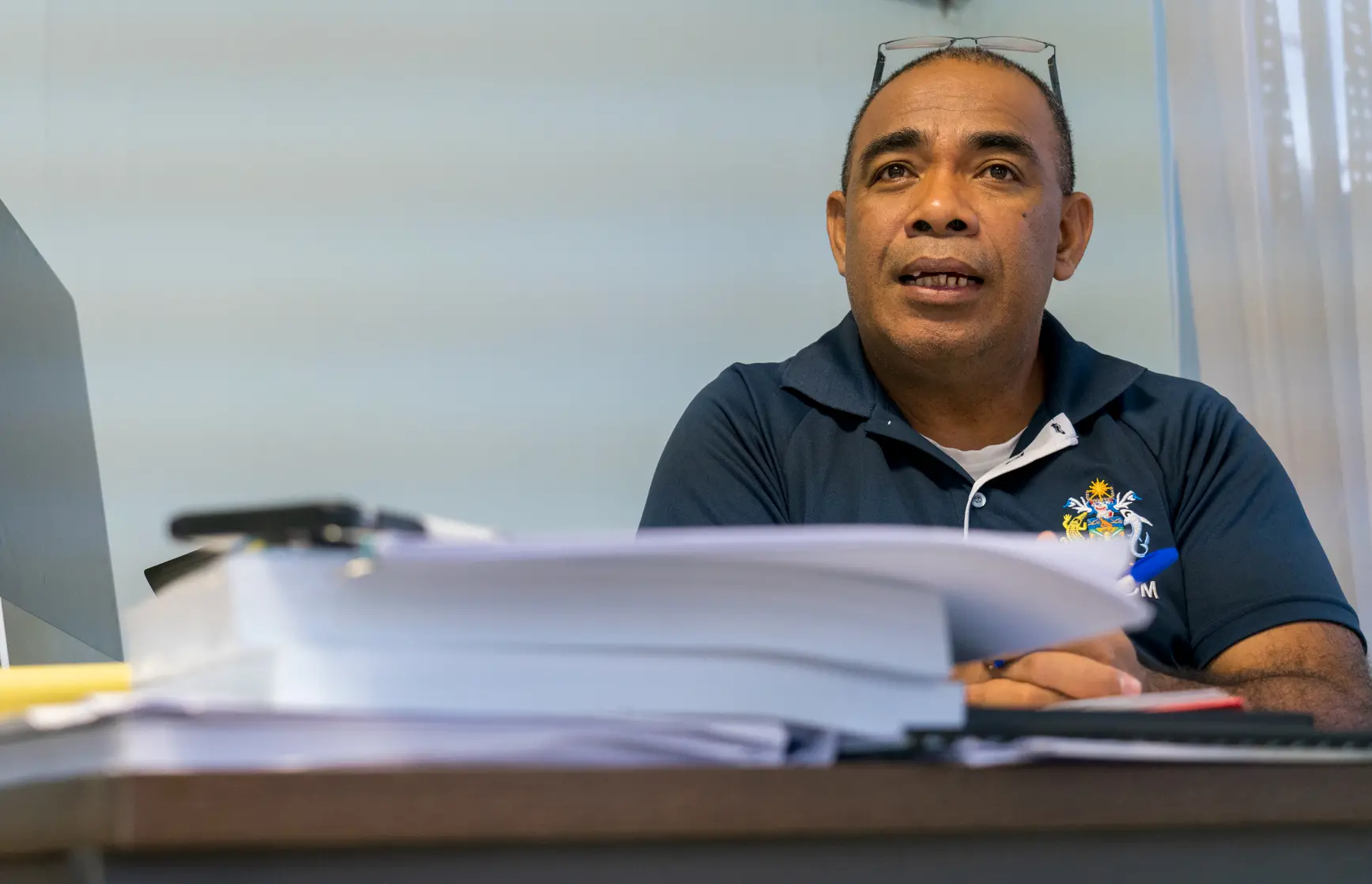

There is speculation that the government will mandate pre-building surveys, as the Ministry of Lands, Housing & Survey readies a new National Urban Development Policy.

The policy, if it were to include pre-building surveys, would stretch an already-overstretched ministry that is contending with a fast-expanding city and several housing developments, according to Robert Misimaka of the MLHS.

But Misimaka acknowledges UXOs are a public health issue. He knows that people are dying on their land doing daily tasks, and that something needs to be done about it. The current urban migration, from the outer islands to Honiara, only underscores the need.

That is especially worrisome because the city is growing eastward, toward the key stockpiles and battle sites of WWII, as Solomon Islanders search for work and money — economic opportunities are slim outside Guadalcanal.

But any requirement for a survey before building will likely be meaningless, says UH history professor Joseph Foukona, who spent his early years at the same school in Honiara as Kabutaulaka, also a UH professor.

The Solomon Islands government’s only land is in Honiara, on perpetual estates, which it leases from landowners for 75-year terms. As the leaseholder, it will be able to impose surveying terms on large swathes of the city, though it will not have the ability to dictate what happens outside the city boundaries — like in eastern Tenaru, the area around Hells Point — as most of the country is private land.

“If you go to Tenaru now, there’s houses everywhere,” Foukona says. “Back then everything was raw, untouched. Now it’s people building — with bombs everywhere — unplanned.”

Some Much-Needed Help

Isaiah Tengata knew calling an ambulance was pointless as U.S. white phosphorus burned into his 11-year-old Senri’s arms. He was just lucky his cousin’s car was close by, so they could make it to National Referral Hospital, more than four miles away.

The road is plied by taxis and white vans, transporting people like Isaiah in and out of the city. But ambulances, typically trucks in medical livery, are an infrequent sight. And even less so throughout the rest of the country.

The Solomon Islands has a universal health care system, but the lack of ambulance service is just one shortcoming. The NRH is plagued by lack of funds, staff, beds and facilities and mismanagement.

If bomb victims are fortunate to have a vehicle available, their chances of survival are higher but still slim, according to Dr. Rooney Jagilly, a surgeon who has worked at NRH for 30 years.

This year, when Honiara was hit with Covid-19, the 350-bed hospital buckled from the demand. Patients died on the floor.

Jagilly estimates no more than 10 victims of UXOs are treated at NRH each year. But neither the hospital nor the government keeps track.

The reality is many bomb victims die before reaching the hospital, Jagilly says. Bombs are designed to kill people efficiently, and even in the best situations with good health care, people die before they can get help.

But even if they don’t, their chances are still not good.

“The injuries are usually very horrific, with the bomb blasts: Open chest wounds or amputated limbs, an unrecognizable face,” Jagilly says.

And what the hospital can do for them is limited by its lack of resources. “There are cases which we would probably be able to save if we had a small high-dependency unit, an intensive care facility,” he says.

It’s not just a lack of equipment. It’s a lack of expertise. There are five general surgeons to service just over 700,000 Solomon Islanders, one for every 140,000 citizens, along with their small teams of surgeons in training.

Compare that to Oahu, which has 64 general surgeons for about 1 million people, one for every 15,000 people. And even that is considered a shortage in Hawaii.

In the Solomons, there are 300 populated islands without ready access to medical facilities, let alone adequate care.

Senri Tengata was fortunate to survive. But he still needs help.

Life Changed, Forever

The father of six children, Isaiah weeps out of exasperation and anger as he tells the story of what happened to his son. His once lively boy has retired into himself and Isaiah fears for his only son’s future. This year his wife died of Covid complications, making life even harder.

He also fears for the family’s safety. He discovered two bombs in their backyard a couple of weeks ago. He does not know if they are live. And he doesn’t know what to do with them, since he hasn’t seen the bomb squad show up.

Senri sits next to him, intermittently fidgeting with his fused fist and tucking it between crossed legs.

He loved school, particularly math, and liked soccer. He played goalkeeper. He was a typical kid from the Solomon Islands.

But he has not returned to school since he picked up the bomb. He’s too embarrassed. He cannot play goalkeeper anymore.

He needs help: extensive, daily rehabilitation sessions and surgery, among other things. He was supposed to undergo rehabilitative treatment at the National Referral Hospital after he was discharged, but Isaiah could not juggle his job at the Ministry of Finance with what would have been an extra two hours travel by foot and bus to NRH.

“It’s a burden. I’m only one man,” Isaiah says. “I’m starting to worry there won’t be any help for my boy.”

But Isaiah believes help has to come: From the U.S. or Japan or Australia or the Solomon Islands own government.

Senri was discharged from the hospital after a month-long stay. Two days later, his civil servant father wrote a letter to the police, with a note from their surgeon detailing the lifelong effects the injuries would have — physically and psychologically. He hoped the police would be able to connect him with the U.S. or Japan or Australia, to get some sort of help to fix his son’s fused hand and get compensation for the cost of his son’s month-long hospital stay.

A month later, he wrote the U.S. Ambassador to Papua New Guinea — the closest embassy. Hospital fees were crippling and his son needed help.

Now, he has been offered glimmers of hope. Soon after he sent his letter to the U.S. Embassy, he was contacted by an Australian physician in Honiara.

Then came a consultation with Australian doctors in Honiara, and a Rotary group organized passports for the family – purely out of goodwill — in the hope flights and surgery could be organized for Senri. The Australian government, nor any other, has been involved.

Most recently, at the end of August, Isaiah received a call to take his son to the U.S. Navy’s Mercy Ship, which stopped by Honiara, where he received a round of laser skin treatment.

Finally, the advocacy of various foreign medical professionals, working on their own time and dime, brought Senri’s case to Rotary Oceania Medical Aid for Children, funded by members in Australia.

The organization has taken on Senri’s case, which means surgery in Australia is imminent. After surgery, he faces arduous and long rehabilitative care.

And bombs are still in the family’s backyard.