Editor's note:

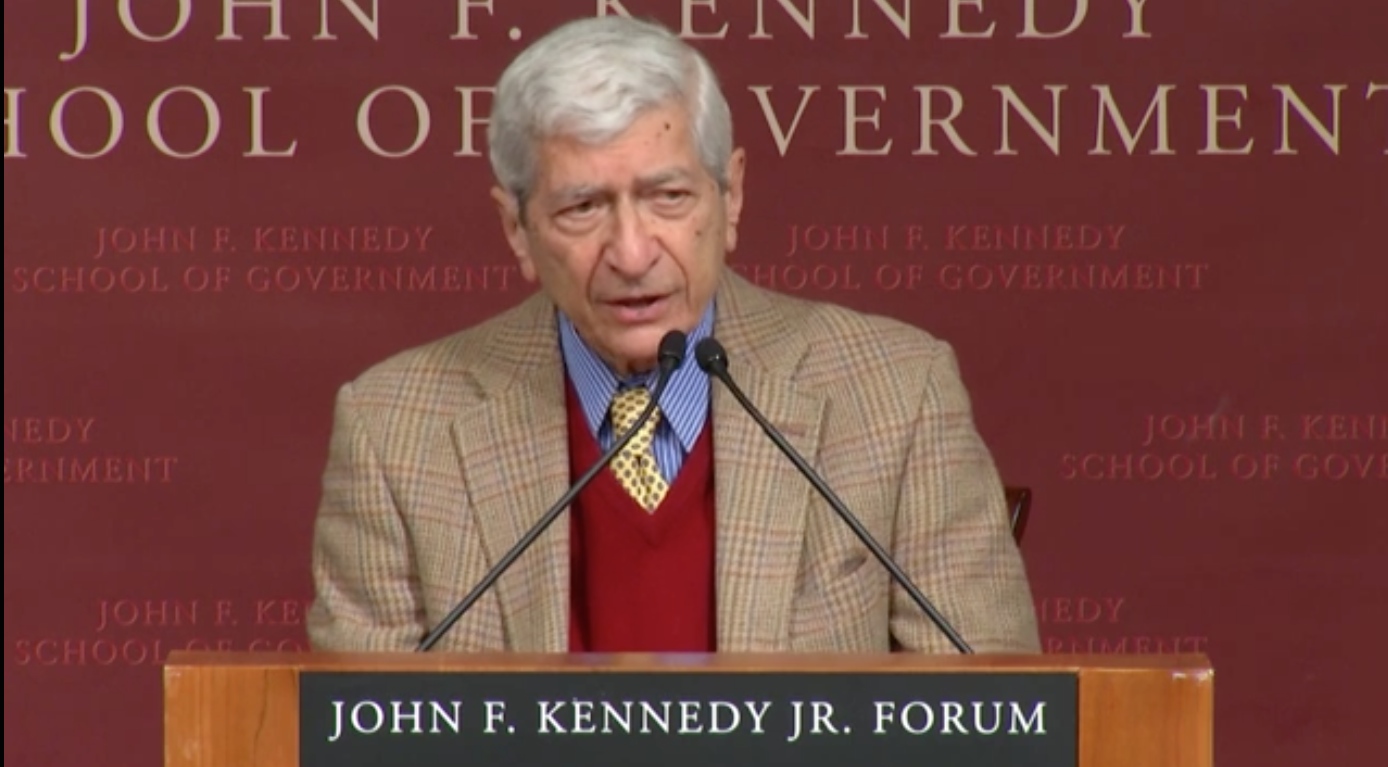

On Tuesday, March 3, Pulitzer Center Senior Advisor Marvin Kalb was awarded the Goldsmith Career Award for Excellence in Journalism. The awards presentation took place at Harvard's Shorenstein Center on the Media, Politics and Public Policy, where Marvin served as director between 1987 and 1999.

Current director Alex Jones, in presenting the award, paid tribute to a storied career that has stretched from work at CBS with Edward R. Murrow to a slot on Richard M. Nixon's "Enemies List" and authorship of 12 non-fiction books. His latest, due this June, is on the crisis in Ukraine.

"The word most often associated with Marvin Kalb these days," Alex said. is 'distinguished.'"

In his remarks, reprinted below, Marvin reflects on the journalism of Murrow's time, the journalism of today, and where we are headed tomorrow. At the Pulitzer Center we benefit from Marvin's wisdom and counsel every day. We celebrate with him and Mady this latest, much deserved, recognition.

Jon Sawyer, Executive Director

You can watch Marvin Kalb's speech here.

Let me start with two stories about a journalist and the craft we call journalism. There may be something in these stories for us to think about.

The first story takes us back to December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Edward R. Murrow, the CBS journalist then covering the London blitz in the early days of World War II, had a dinner date with President Roosevelt, made weeks before. He was sure it would be postponed, given what had happened earlier that day. But Roosevelt wanted to hear about how the British people and the British government were holding up during the blitz. Murrow was informed that dinner with the president was still on, but it might not start till after midnight. Was that OK? Yes, it was.

During dinner and after, Roosevelt asked Murrow about the Brits and the blitz. Then, he turned to Pearl Harbor. Murrow, like most Americans, knew only what the White House had released earlier in the day—the surprise Japanese attack, American casualties, ships and planes lost. No more. We did not have "live" broadcasts back then. We could not see the destruction, nor interview people caught up in the confusion and turmoil. Roosevelt, setting no ground rules--what was on the record, or off-- proceeded to fill in many of the blanks—the number of ships sunk, the number of planes destroyed, ("on the ground, by God, on the ground," Roosevelt lamented), and of course the number of Americans killed and wounded. These were not exact numbers. They were estimates—it was still too early after the attack--but exact enough to paint for Murrow a dismal, depressing picture of an unforgettable moment in American history. There was no longer any doubt in his mind that the US was going to enter World War II.

Roosevelt also told Murrow that on December 8, he would go to Congress and request a declaration of war against Japan—the last declaration of war, by the way, ever requested by an American president, though we have been in many wars since. But that's another story.

When this extraordinary briefing was over, Murrow left the White House with a question on his mind. He had a great story. No doubt of that. Roosevelt had never said, "off the record." In fact, there were no ground rules at all. Murrow could have gone to the CBS bureau and done the first report on the true costs of Pearl Harbor. In fact, maybe that was what the president really wanted (and expected) him to do. Roosevelt was, after all, no innocent in press management. He understood the game of politics, and the role of the press in it.

But Murrow did not do a broadcast. He returned to his hotel room to think about what had happened to America that day, on December 7, 1941, and then to think some more.

Later in the morning, Murrow went to Capitol Hill to hear the President request a declaration of war. That night, on CBS radio, Murrow's report was a work of art—rich with detail, much of it still new, thoughtful, well-written, important.

Question: What would the Murrow of today do with this kind of presidential exclusive?

My second story also concerns Murrow. Only the date and location have changed. It is now April 12, 1945 (the day Roosevelt died, by the way), and the place is Buchenwald, a Nazi death camp, liberated that day by General Patton's Third Army. A small group of reporters, including Murrow, visited Buchenwald. He smelled death ("evil smelling," he later wrote). He saw corpses stacked like cord wood. He saw men too thin, too weak to get out of bed—12-hundred men in a stable built to hold 80 horses.

During this visit, Murrow did something he would not normally have done. He had won a lot of money the night before, playing poker, and he kept giving it away, small gifts to the liberated prisoners who approached him. On reflection, it's clear Murrow was overwhelmed by what he had just seen—what man was capable of doing to other men.

When he left Buchenwald, Murrow could not find the words to report on his visit. Other reporters could, and did; but Murrow could not. For three days, he suffered with a search for the right words. When he found them, he composed one of the greatest reports in the history of broadcast news. I hope everyone here will take the time to listen to it. In fact, with the rise of Islamic fanaticism and anti-Semitism in Western Europe in recent months, this may be the right time to listen to Murrow on Buchenwald.

"Permit me," he began, "to tell you what you would have seen and heard had you been with me on Thursday. It will not be pleasant listening. If you are at lunch, or if you have no appetite to hear what Germans have done, now is a good time to switch off the radio." Then, with a contained passion, delivered with his characteristic staccato beat, he described the camp, the emaciated bodies, the anguished look in the survivors' eyes. He hoped his words, the pictures they drew, could somehow convey the reality of a Nazi death camp. But he wasn't sure.

He closed with these words: "I pray you to believe what I have said about Buchenwald. I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it, I have no words."

Another question: How would the Murrow of today deal with a Buchenwald-type story? Perhaps a more appropriate question would be—can there be a Murrow today? Someone who has a December 7 exclusive, with the president, no less, and doesn't report it? Someone who could wait three days before telling the story of Buchenwald? My sense is CBS would not take kindly to that kind of reporting.

In the journalistic arc from Murrow to, let us say, Brian Williams, it could be argued that not only the business of journalism but the very definition of journalism has changed dramatically and irrevocably. In, out, next—that is the rapid, relentless rhythm of contemporary news-making. In, out, next. On the other hand, thinking, reflection, perspective—that's all well and good but not for now, and maybe not ever.

It could also be argued that journalism as a craft has not changed at all. Only the technology has changed. Like the Gutenberg Bible, like the telegraph in the 1840's, like the Internet today, the technology keeps changing, but not the craft of journalism. It is still the same effort to find out what's going on, and tell people about it.

Maybe, 20-30 years from now, when we look back upon this time, we'll learn the true impact of the digital age on our democracy. We already know its impact on journalism—fewer newspapers, tighter budgets, continuing cutbacks, personal anxiety, less respect for the industry and its product. Fighting this obvious and depressing trend is the mushrooming of alternative journalistic enterprises, mostly on websites, which provide not only jobs but hope for the future. I have in mind GlobalPost, for example, and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, where I currently hang my hat, and others such as ProPublica. Everyone is trying to find a workable, sustainable financial model for modern journalism. Of course, a friend with a fat wallet often helps—the Washington Post knows about that.

This is not exactly the right moment to sit back and figure out where we are in American journalism. In the last month or so, we have all lost a courageous journalist in CBS's Bob Simon, a remarkable journalist in columnist Arnaud de Borchgrave, an incredibly talented journalist in David Carr of the New York Times. We have also lost, if that be the right verb, Jon Stewart of Comedy Central, the man more undergraduates turn to for their daily news fix than any other TV performer. And we have all watched the evening news on television descend another step toward irrelevance, when NBC's chief anchor man, Brian Williams, was forced to step down for six months—I think it will be a lot longer—charged, charitably put, with a modern TV version of self-aggrandizement. Clearly he exaggerated his role in covering the Iraq War and the Katrina storm, something other anchors, such as Fox's Bill O'Reilly, have also been accused of doing. On talk shows, Williams seemed to boast about his role as a reporter, the risks he faced, the courage he showed—all, I suspect, in an effort to beef up his ratings for his nightly news program, forgetting that, whether on talk shows or nightly news, he was the face of NBC, and many people believed him. O'Reilly, in a similar situation, reacted by fighting back fiercely, and then watching his ratings soar by 10 percent. Why did Williams do what he did?

One, because he is a terrific story-teller. He loves to spin a yarn. And, two, the pressure of ratings drive TV anchors, newspaper columnists, probably even university professors, to push the boundaries of truth-telling to attract a wider audience—sometimes for no reason more compelling than the desire to get a return invitation. Truth in the digital age has become a slippery commodity, exploited, expanded and manipulated for maximum personal or professional advantage.

My concern is the effect of digital reporting on our democracy. In the mid-1990's, I did a research paper for the Shorenstein Center called The New News, my modest attempt to explain the changes then rocketing through the industry. Looking back, I realize I barely scratched the surface. We have, in fact, been living through a revolution in communications, unlike any the world has ever seen or experienced before. It's Gutenberg to the n-th power. It affects everything—reality and our perception of reality. We see and understand things through the many prisms that compose the digital age—the ubiquitous iphones, Twitters, social media, Instagrams, and all the rest: new today, discardable tomorrow. Nothing any longer seems durable. Books become relics overnight.

We are understandably fascinated by the new news, the new technology, the digital age. But so is the Islamic State. So are Presidents Obama and Putin. The world is now wired for instantaneous communication, everyone searching for, and expecting, immediate answers and gratification. But think for a moment about the consequences. For example, a morning Poroshenko comment in Ukraine becomes instant fodder for analysis, and decision-making, often by journalists and even by presidents. What's new here is the speed, and the effect of the speed. It has come to be expected that, by the noon briefing, or sooner, the administration will have produced an official policy statement, or an evasive non-statement, in response to Poroshenko's comment.

Let's say the question is: Should we send lethal weapons to Ukraine? Yes, says a ready Senator McCain. He's on television more than some anchormen. Yes, echoes a Washington think tank, Brookings in this case. No, for God's sake, implore a few professors. If someone is keeping score, the yes's seem to be winning the debate. Mid-afternoon, and an always reliable source hints that the President is close to a decision. By evening news time, the White House says, definitively, that the president has not yet made a decision—that he is still "thinking" about sending lethal arms to Ukraine. Reporters frown. They've heard this all before. Their copy reflects their impatience. They write, or broadcast—The President is again wishy-washy—he cannot make a decision. He is indecisive, a poor leader. This judgment is made in Washington; it becomes instantaneous wisdom in the rest of the world.

Tom Brokaw calls this the "big bang theory" of modern day journalism and, I should add, public policy deliberation. Presidents, frustrated by much of this often mindless chatter, seek new ways to go around the mainstream media directly to the voter—an unfortunate pattern of evasion that presidents from Richard Nixon to Barack Obama have employed to duck the inquisitive reporter. Put off by the headline writers, understandably perhaps, and aware that only 20% of Americans between the ages of 18 and 24 actually read a daily newspaper, President Obama now prefers to give interviews to targeted audiences—generally websites, such as Re/Code, Vox, Buzzfeed, or, more recently, You Tube, where younger audiences get their news. The websites are quick and appealing, and so far anyway, demand little of him. Dan Pfeiffer, Obama's media guru until recently, was absorbed at the White House primarily with politics in the digital age. "We're on the cusp," he said, "of a massively disruptive revolution." A revolution, I suspect, that will also have profound consequences for our democracy. Rather than deliberate, if necessary slowly and carefully, we are pressed into quick decisions by the relentless demands of digital technology, where little priority is reserved for the careful consideration of policy options, even those of war and peace.

I know that we have all survived, some of us have even prospered, as a result of earlier technological revolutions, and maybe we'll survive this one too. The thing is, we don't know. In a revolution, such as this one in communications, we can't know till it's over. Crane Brinton used to say the same thing here about the French Revolution. But when it is over, I fear, we may only be left with a tattered, fragile version of our once vibrant democracy.

Allow me, for a moment, to invoke Murrow once again. Way back in 1958, when his best days as a reporter were behind him, Murrow wondered whether the new technology of his day –namely, television—was helping or hurting our democracy—whether it was raising educational levels, making people smarter, more knowledgeable, about national and world affairs, or whether it was doing no such thing? He concluded that television, in the preceding decade, had failed the American people, producing, in his words, "decadence, escapism and insulation from the realities of the world in which we live." I think Murrow, were he alive today, would find little reason to change his judgment. And with what is now called cable news, he would, I suspect, be even more inclined toward his original judgment.

He did advance a possible solution. I advance it again this evening, but I don't think it represents our salvation, even if accepted, and acted upon—and that is, that each of the 20 or 30 major corporations sponsoring radio and TV programs devote an hour or two every year to the networks for a discussion of important issues, like presidential elections and war and peace. That would represent minimally 20 or 40 hours of additional programming on these issues, all without the usual six-minutes/an/hour set aside for commercial breaks. That would also represent a big step forward toward elevating television news from where it is today to where it still could be. Murrow's idea was not accepted in 1958, and I doubt that it would accepted today either.

Murrow's concerns, though, ought to be explored. He described the American people as "wealthy, fat, comfortable and complacent." True then, probably today as well. He then quoted columnist Heywood Broun as saying, "No body politic is healthy until it begins to itch." Murrow in this sense wanted us to itch, and what produced the itch, as he saw it, was good television. It has awesome potential and its influence and power are still pervasive. It has even invaded the iphone, the new wristwatch, and much else.

But, in Murrow's view, "if…this instrument is good for nothing but to entertain, amuse and insulate, then the tube is flickering." Then, he added this short paragraph, which has been quoted endlessly. "This instrument can teach, it can illuminate; yes, it can even inspire. But it can do so only to the extent that humans are determined to use it to those ends. Otherwise, it's nothing but wires and lights in a box." Today, we know, it's wires and lights in a cloud, no longer a box, but the same challenge beckons to the leaders of American media—and, as important, to American journalists operating under severe financial and technological pressures.

We are still a free and open society, and, in my experience, the best lubricant for a free and open society is a virile, unafraid press, doing its constitutionally-guaranteed job of finding out what is going on and telling us about it, even if people in authority do not like what you are telling us. With a free press, the sky's the limit. Without it, we are, to quote a former president, in deep doo-doo.

I close now with a story about my undergraduate days at the City College of New York. I took a course in creative writing, thinking one day I could be a writer. Professor Teddy Goodman was my teacher. He asked his students to write short stories, measuring them all, in fits of wild exuberance, against James Joyce. Every week a student or two would read his short story to the class, invite comments, good or bad, and then Goodman, standing in the back of the room, would walk to the front and pronounce, yes, you may be a writer one day, or no, enroll in a dental school.

One day my turn came. I read my story. I thought it was pretty good. A few students agreed, and then came the Goodman moment. He strode to the front of the class. I thought I saw a mischievous look in his eyes. He asked for my story. I handed it to him. He glanced at it, looked at me, and pronounced, "this is a very promising story." And then he paused, but for only a moment, before proclaiming, in a loud theatrical voice, "for the wastebasket," at which point he threw my story into the waste basket. I was left in a state of shock, my mouth open, tears forming, before I rushed out of the room only to hear Goodman shouting after me, "Kalb, all you will ever be in life is a journalist."

Poor Teddy Goodman. He didn't realize he had just paid me the ultimate compliment.

Thank you.

You can watch Marvin Kalb's speech here.

You can listen to Edward R. Murrow's report from Buchanwald Concentration Camp here.