Pulitzer Center Update June 12, 2017

Gender Lens: Fundraising Proposals and Pitching

Journalists and media professionals packed the room on June 4, 2017, the final day of the Pulitzer Center's 2017 Gender Lens Conference to hear directly from editors on how they select pitches at the Fundraising: Proposal and Pitches Workshop.

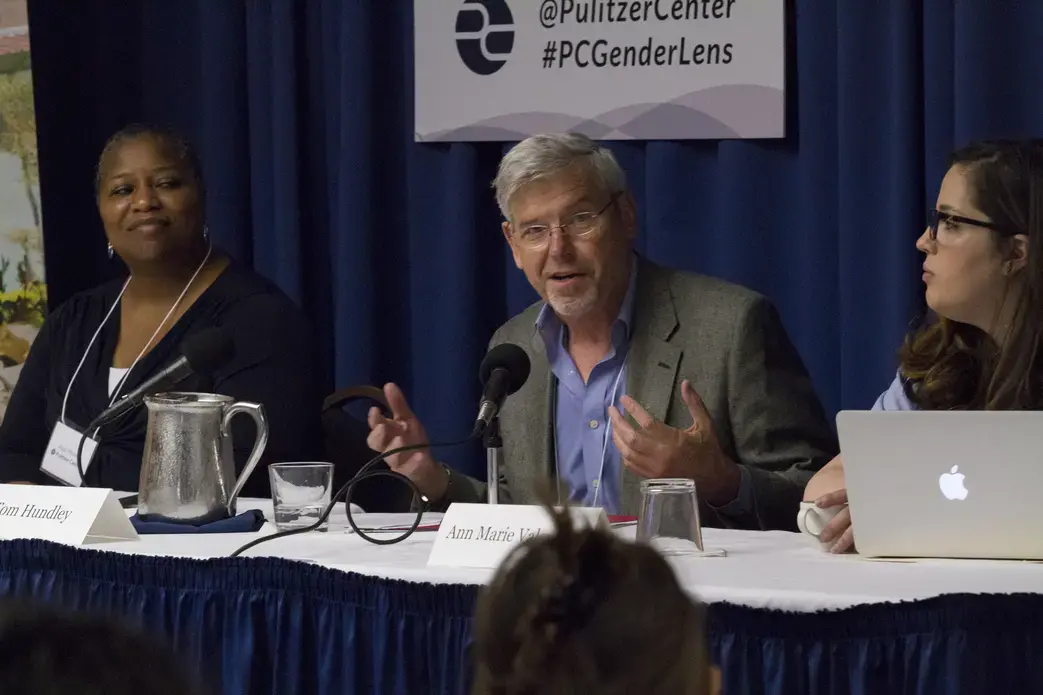

Pulitzer Center Capital Campaign Director Joan Woods moderated the panel, introducing Senior Editor Tom Hundley, and International Women's Media Foundation Senior Program Officer Ann Marie Valentine, both of whom are instrumental in the grant selection processes at their respective organizations.

"We get about five or six hundred applications a year, and we have the resources to support about 120, 150 projects," Hundley told the audience. "The really crappy part of my job, the part of my job I actually hate is, I have to say no to a lot of really good projects. So what I'd like to talk about today is how to get your story idea over the hump."

Upon rejection, many grant applicants often question what they did wrong, why their project didn't make the cut. Both Hundley and Valentine encourage grantees to try again, because, as Hundley explained, "even if you do everything right, you still might get turned down. Either because we simply don't have the resources to support every good story that comes our way, or because I wasn't smart enough to see the real merit of your proposal. I hate to think of how often that must happen. I see a few people shaking their heads." Previous Pulitzer Center applicants in the audience—both successful and not—chuckled in agreement.

Both panelists gave hope though, addressing "how to avoid the obvious mistakes and deal-breakers and what goes into a really good pitch." Each organization distributed tip sheets on how to formulate a successful pitch.

Hundley shared his process for sending "fairly anodyne" rejection letters. "I leave the door open."

He did share a less anodyne rejection letter from 1984 written by an editor at San Diego Magazine giving what Hundley described as "tough love" to veteran, multiple Pulitzer Center grantee Jon Cohen. The letter opened with, "Dear Mr. Cohen, Cute. But give me something I can use." It ended with "Marketing, marketing, marketing. Go to work, bozo."

"That's an editor who really cares, really," said Hundley. Over seven years and more than 2,000 story pitches, his favorite was one from Nell Freudenberger for a nonfiction piece published in Harper's on India's disappearing Parsi community. The pitch length was double the Pulitzer Center's limit of 250 words, which the audience later challenged, but captured his attention with a stark, carnal lede describing the Parsi tradition of exposing their dead to vultures, embedded within a lyrical and thorough explication of the Zoroastrian community's place in history and the grim prospects for its "demographic future."

"It's beautifully and economically written. She shows me in the first few sentences that she's a polished writer with the skills necessary to write for a publication [she's pitching]...second...in those 500 words she demonstrates that she knows how to organize a piece of writing. It has a lede...it has a nut graf, this is the graf that tells you why the story is important, why it matters, why you should read it all the way through, and why the Pulitzer Center should fund it." It included historical background, proving Freudenberger's knowledge of the subject, and conveying the significance of the story while creating a strong sense of place. It sketched a basic arc for the story, including main characters and what they'll have to share.

Pitches will vary for photographers and documentary makers, but these are the basic, most necessary ingredients.

Valentine dove into IWMF's wide variety of grant opportunities, outlining the annual Courage in Journalism and Photojournalism awards, the Elizabeth Neuffer Fellowship, and reporting initiatives in the African Great Lakes region and Latin America, which include a hostile environments and first aid training, and a week and a half of in-country reporting in those regions. Each of those regional initiatives also offers year-long in-country fellowships for journalists based there.

The "biggest opportunity" IWMF offers comes from the Howard Buffett Fund for Women Journalists, which receives between 500 and 800 applications per round, twice a year. The Fund considers applications "for anything from books, documentaries, podcasts, investigative reporting, language classes, conferences, hostile environments trainings. So talking about an application the Buffett Fund can be a bit difficult because we try our best not to be prescriptive in what you may want to do." An example of a project that received support from the IWMF's Buffett Fund is the Argentinian fact-checking site, Chequeado.

The basic proposal elements Hundley outlined are the same for the IWMF, but the details really depend on the project. "But the larger goals of the Buffett Fund are to fund projects that focus on under-reported but critical global issues." That said, the IWMF selection committees "are really most attracted to projects that take a larger global issue and bring it down to a more human, nuanced scale."

Whereas at the Pulitzer Center, Hundley selects a shortlist from the week's applications and reviews them for final selection alongside Executive Director Jon Sawyer and Managing Director Nathalie Applewhite, the IWMF pushes applications first through selection committees composed of volunteer readers including former grantees and fellows, and working journalists, and then onto a formal committee.

But in a pool of so many applicants, what helps journalists stand out? Woods asked the panelists to share advice for younger, early-career journalists as they try to get in shape to apply for Pulitzer Center and IWMF grants.

What the IWMF likes to see "are proposals that have a little more editor collaboration at the front end....If you can succinctly describe some measurable goals and deliverables and a timeline in which you'll submit them, if you're upfront about the challenges that you might face and how you plan to navigate them, and that includes any security risks...For the Buffett Fund, we encourage people to include stipends to pay themselves for their work. But also be realistic."

One of the biggest pitfalls for IWMF applicants are pitches that try "to do too much. So they may pitch their own website, along with a training, and a video, and a series of stories, and it's just too big to get your head around."

Questions from the audience covered a wide range, from inquiry into opportunities for mentorship between applicants and grantees, to if it's ever okay to share information for free, to why organizations require letters from editors when editors are wary of accepting pitches without a funding plan.

Valentine joked that the IWMF usually refers people first to the Pulitzer Center. She added that they do want more pitches from international journalists wanting to report on issues in the U.S. Hundley laughed—the Pulitzer Center's mandate is to support international reporting, so he offered to send the many applicants that don't fit the bill to IWMF.

Valentine noted a common insecurity she sees among IWMF applicants. "You are qualified to apply for grants just like everybody else. You might not get a grant your first time out of the gate. But I see a lot of people coming to us sort of asking for validation on their ideas...it's really hard to say. We could get a stellar batch of 800 amazing applications which will make the competition more difficult, or we could get a bunch of duds and you might win a grant."

Hundley had a shorter nugget of advice. "For young journalists, I have two words: Ben Taub. You saw him last night. I think he's 25. No, seriously, that's unfair."

In response to Hundley's remarks, Pulitzer Center grantee Jina Moore, now a global women's rights correspondent for BuzzFeed News, asked a question that sparked productive discussion around privilege and the objectivity of the grant selection process.

"Ben's a tremendous journalist," she said. "But it doesn't escape my notice, especially in this room and at this conference, that the kind of stratospheric opportunities that Ben has had the advantage of tend to fall in the laps of white men from elite institutions. And I wonder if you guys know about mentorship networks that those of us who don't come into these spaces with that kind of privilege could avail ourselves of." The crowd applauded.

"I think we're all very aware," Hundley said. "Applicants send us their CVs, we note where they've gone to school, their race and ethnicity, you know, you can't help it—we noticed that there is a clear advantage to people who have gone to elite schools. And we actually do try to counterbalance that."

Another lively back-and-forth centered on the power of the nonprofit journalism community to leverage its burgeoning urgency to hold outlets accountable for paying journalists adequately, on time, or at all.

For Pulitzer Center grantee Elliott Woods, publications are asking more and more that he find a way to fund story pitches with a grant. "That doesn't bother me very much when it's a little tiny magazine that I know doesn't have very deep pockets. It bothers me alot when I know that it's a magazine that has a midtown Manhattan office and where everyone gets their lunches expensed. I don't know if that actually happens...but I worry about that dynamic…I wonder what you all feel about that as you become increasingly important to this business for even major publications...And I also wonder about the question of grantmaking organizations becoming in that way a second set of gatekeepers, and how you're navigating that."

As Hundley explained, the Pulitzer Center sees its role as covering "the hard costs of doing the story. We're not paying you for your work. We're not giving you a stipend. That's up to them...you've got to pay the writer or the photographer for his or her work."

Valentine agreed. "It's a slippery slope...I think in supporting the journalist, we never want to be in the position of picking up the media organization's slack where they fail."