The COVID-19 pandemic forced almost 90 percent of the world's museums to close their doors for varying lengths of time, affecting over 85,000 institutions. Nearly 13 percent may never reopen again, according to UNESCO.

With the help of 16 freelance journalists, the Pulitzer Center-supported Prairie State Museums Project set out to highlight the pandemic's impact on museums across the state of Illinois, focusing on the role these institutions play in local communities.

A part of the Pulitzer Center's "Bringing Stories Home" reporting initiative, the Prairie State Museums Project "drew our attention because it was unique," according to Pulitzer Center Senior Editor Tom Hundley. He noted that while media coverage during the pandemic focused on the world's largest museums in Washington, New York, and Paris, the experiences of local institutions need to be told as well.

"The struggles of one museum in a mid-sized city in Illinois is not going to attract much notice, but when you bundle a dozen or so of such museums together in one project, then you've got a story with real heft, a story that touches a lot of people and a lot of places," Hundley said. "It is exactly the kind of important but under-reported [story] that defines our mission. The Prairie State Museums Project has a lot of moving parts, but it has been very well organized and executed from the start, and we are delighted with the results so far."

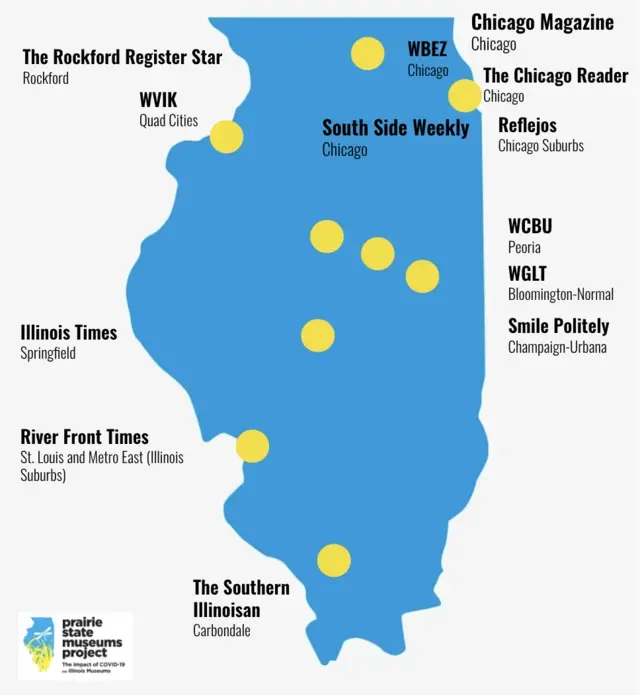

Ultimately, the project produced over 30 articles for 13 state publications and one national media outlet. Its reporters documented the diversity of Illinois's museums and the communities they serve, telling the stories of cultural spaces from a Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house in Rockford to the Katherine Dunham Museum in East St. Louis.

To learn about the origins, mission, and execution of the Prairie State Museums Project, Pulitzer Center General Intern Ethan Ehrenhaft spoke with Project Director and Principal of Resilient Heritage Daniel Ronan. The following Q&A between them has been edited for clarity and length.

Ethan Ehrenhaft: What was the significance of covering Illinois museums in the middle of the pandemic?

Daniel Ronan: The reason why I took on this project was to really support museums at a time when a lot of sectors are hurting. Museums are one of the longer-affected sectors because they have to close first and then they stay closed the longest. In many ways, arts and culture are not considered essential. To me, I think arts and culture are definitely essential. I wish people understood that [museums] bring a lot of value to their communities from an economic and cultural aspect. I wanted that to be the focus of this project, pandemic or not.

As someone who's lived in Chicago for seven years now, I have noticed this upstate-downstate divide. That divide is very present in the cultural makeup of our state. I thought that a statewide project in particular could bring together journalists in a way that arts and culture bring together people. I hope that one of the legacies of this project is that we think about Illinois as a broader state and start to forget about the things that divide us and come together around supporting the things that are very meaningful to our communities, both in Chicago and downstate, from Chicago to Carbondale.

EE: Your project description talks about how "both museums and journalism are the bedrock of an informed democracy." I think the media has reported frequently in recent years on the struggles of local journalism and how essential it is to state-level democracy. Do those themes and struggles run parallel to those of local museums? Do museums occupy this similar niche in local communities?

DR: Yes, I would say local journalism and museums are quite similar in the sense that they offer a space for people to listen to and debate ideas. We've lost those spaces in many ways, as we lose a local town paper or a cultural institution. It's become really apparent to me that Americans are starting to rethink the need for those spaces. I would hope that projects like this elevate the idea of having spaces to talk about the issues of our day, because they're only getting more numerous. Without those forums to raise an idea, I think we lose a sense of who we are.

As Americans, we're always supposed to be questioning and pushing new ideas, but if we don't have a forum or a space to do that in, how can we? I feel that [local museums and journalism] are similar in many ways. I don't think Americans necessarily see the value in either until they're gone. But I do believe that we are coming to a point where hopefully that change may be on horizon.

EE: Journalism and museums are both institutions that can hold the areas around them accountable. Did you get a sense of that with this project?

DR: It's interesting because there's this idea of journalism of being impartial and unbiased. I think what we've seen is that the systems that govern our society are never unbiased. Museums are critical in having us realize where our biases are and show us that that takes conversation, that takes dissection, and that takes work to get at who we are and why. Good journalism does the same thing.

A good exhibit and a good article in the Sunday paper do wonders for how we act towards one another and how we associate ourselves with the duties we have as citizens. In many ways, I think there are parallels to be had between museums and local journalism, because it activates a part of ourselves.

I read a newspaper, and I learn about an interesting issue. I go to an exhibit, I have that same sort of feeling: "wow, I didn't know about that topic." It could be an art exhibit that shows me someone's personal experience in a conflict zone or a history exhibit about women's suffrage. There are so many ways that both stories from the paper and stories from museums can inspire one to action. That's sort of a feeling I wanted this project to bring to someone who sees the diversity and representation of this project and is inspired to continue seeing museums and their work.

EE: This project's 16 journalists come from such a range of backgrounds and experiences in the field. How did you go about remotely recruiting and organizing a team of this size?

DR: I spent a lot of time pulling it together and it was very much a nonstop [process]. What I tried to do was identify news outlets from across Illinois that really spoke to the broader geographic and community diversity of the state. I was successful in getting some news outlets and wasn't successful with others, but considering the short timeline I'm happy that 14 of the news outlets agreed to participate.

What I did was I leaned on the news outlets themselves to select freelancers that they've worked with before, noting Pulitzer and my desire to make a more representational journalism field. [We] really tried to make sure that the journalists on this project reflected the diversity of Illinois and more importantly, I would say, that these journalists reflected where coronavirus has had the most impact, and that is in communities of color, where there are more infections and more deaths as a result of COVID-19.

That was very important to me, because the Pulitzer Center and I both agree on diversifying the field of journalism, but also it's important that the stories of communities of color are reported on, period. I don't necessarily think that happens and I wanted that to be a project outcome of this collaboration.

In addition to that, [there is] this idea that having diverse perspectives and experiences represented across the journalists allows for better journalism in the collaboration context. Because people bring new ideas to the conversation, people have different ways of seeing issues. I think it made the stories all the more meaningful and the news coverage really stands on its own in representing that idea.

EE: What are some ways the pandemic has changed communities' relationships with museums and how will museums have to adapt their programming going forward?

DR: I think many of us who've been in quarantine have been left out of our traditional cultural places. We haven't had the opportunity to connect with those spaces, which I think has left us seeking new outlets for our need for culture. Honestly, there's tons of people watching Netflix right now, but that is a form of culture and storytelling. What I'd like to think and what I've started to see is that there's this move of the museum space to online interactions or experiences.

I think that's great because it's upping the accessibility of the institution. It poses some questions at the same time for these institutions about whether they need to monetize that experience, or how they're going to monetize it, to help their bottom line. As the pandemic has come in and changed the idea of what it means to visit the museum, I would also like to think, as we go back to some semblance of normal, that people also begin to value or value even more this physical, visceral relationship of experiencing museums in their actual space.

That, I think, has something to do with how communities see themselves. You'll notice it on this project. Three large cultural institutions in Chicago—the National Museum of Mexican Art museum, the DuSable Museum of African American History, and the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts & Culture—are spaces that these communities created for themselves to be heard. I think that's a really critical story when it comes to valuing these institutions as places for one's culture to be not only heard, but valued. During the pandemic, I'd like this to be an exercise in valuing these places even more.