TAPACHULA, MEXICO—Rosa Gonzalez arrived in the shelter here after leaving her native El Salvador suddenly in late summer, fleeing her small town with her older brother and a few possessions, hoping to avoid becoming yet another murder statistic at the hands of her country’s violent gangs

Rosa’s problem hadn’t started with the gangs, but with her husband. He drank, and when he was drunk enough he liked to beat up Rosa. One night, earlier in the summer, he came home and beat her up again. For Rosa, it was the last straw. She took her two kids and left. He begged her to come home, but she refused. Then, desperate, he swallowed poison, was taken to the hospital and died.

She was racked with guilt, but there was another problem: His suicide triggered the fury of his brother, a high-up local gang leader. “They blamed me,” she said. Rosa—who asked me to not to use her real surname for this story, for her safety—went into hiding, living with a friend in another neighborhood. But the gang members started threatening her 28-year-old brother. Gangs in El Salvador have deep reach, holding entire communities in their grip, and they often follow bloodlines for revenge. She knew neither she nor her brother would be safe if they stayed. She took her kids to a family member’s house and left them there. Then she and her brother fled their town, fled El Salvador and kept traveling north.

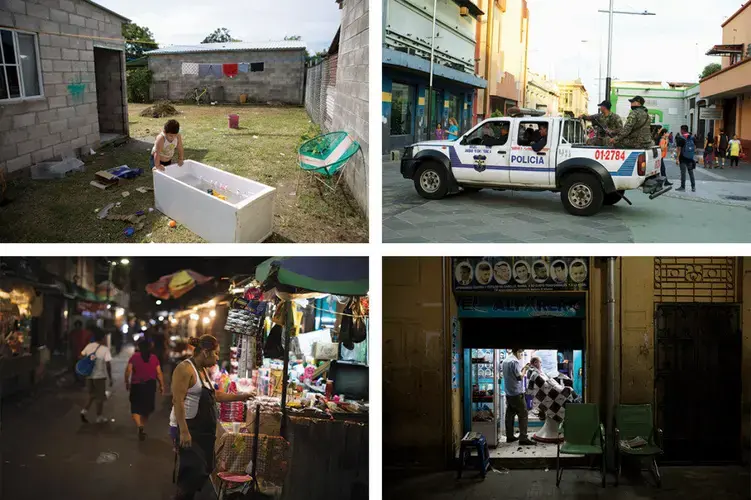

I met Rosa in this small city in the southwestern state of Chiapas, Mexico, in September, almost two months before the thousands-strong “migrant caravan” came through—mostly Central Americans moving toward refuge in the United States. Tapachula is a popular way station for people fleeing Central America for the United States, and Rosa spoke to me in the modest eight-room shelter where she’d been living for a little more than a week. The shelter is an open-air compound where dormitories packed with bunk beds, a kitchen and a cafeteria surround a central courtyard, and it is filled with migrants like her, almost all of them Central Americans forced out of their homes by local violence and in search of safety. Some, like Rosa, are heading for the United States; others are making alternate plans.

If Rosa had been forced to leave a year ago, she told me, she would have brought her children with her on the journey. She’s guarded when she talks about them, showing little emotion, as if she’d fall apart if she let herself think too much about her kids. But she had watched Salvadoran television news reports about what had happened north of the border, with children—some still breast-feeding, some still too young to talk—taken away from their mothers and fathers after reaching the U.S. side. The stories were heavily covered in El Salvador, as they were in the United States—in newspapers, on social media, on television. “With them there,” she told me about leaving her kids behind, “you at least know they are OK and who is taking care of them, and you might even get to see them again one day.” Maybe she’d send for them if things worked out in the United States. Maybe one day things would be different in El Salvador and she’d go back home. For now, it was all theoretical; all that mattered was keeping everyone alive.

Across Mexico and Central America, the calculations of millions of would-be immigrants are shifting, as the Trump administration makes a series of restrictive moves designed to stanch the flow of undocumented migrants into the United States. President Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful wall” hasn’t materialized (long sections of the wall pre-dated his presidency), but he expanded Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s priorities to include undocumented immigrants without criminal convictions, leading to a spike in immigration arrests. His 2017 travel ban, though it largely didn’t apply to Latin America, drew the world’s attention to tougher new U.S. policies. Most recently, and most dramatically, the administration began separating parents detained at the border from their children. The family separation policy prompted outrage and dominated the daily news in the United States, before it was suspended in mid-June. Still, the White House is reportedly considering a new plan that would give apprehended family units a choice after up to 20 days of detention: either indefinite detention together, or separation.

For decades, U.S. immigration policies and border enforcement strategies have been based on deterrence: If you make conditions unpleasant for migrants and make sure people know about them, the thinking goes, people will decide against trying to enter the country illegally. Trump himself has made it no secret that he’d like to end migration at the source. At the United Nations General Assembly in late September, Trump said the only solution to the “migration crisis” would be for people to stay and “make their countries great again.” On Monday, after news reports surfaced of the caravan traveling from Central America, Trump blamed “our pathetic immigration laws” and tweeted threats to cut off aid to Central American countries because they were “not able to do the job of stopping people from leaving their country.” The Trump administration was banking on the rumors and news of family separation making their way to Central America and stopping would-be migrants in their tracks.

Is it working? While it might seem like a rational approach to immigration restrictionists in the United States, the strategy looks a lot different from the other side of the U.S. border.

Most experts agree that would-be immigrants like Rosa aren’t deterred in significant numbers by American policies, no matter how tough, because the threats they’re fleeing at home are far more frightening. And the numbers certainly indicate migrants are still coming. In May, before the height of the family separation coverage, 9,485 family-unit members—the way immigration counts parents and children traveling together—were apprehended along the southern border. In August, in spite of the intensive news coverage of family separations, 12,774 were apprehended. In other words, after three months of American and Central American news saturated with the stories of family separation, border apprehensions of parents with their children actually increased 35 percent. And in September, more than 16,000 family units were apprehended at the border—the highest number on record.

Yet Rosa’s story suggests that the reality is more complicated—that would-be migrants are aware of these policies, and are, in fact, changing their plans. In certain ways, this deterrence strategy is working—yet not necessarily in the way the U.S. government may intend.

In early September, I traveled to El Salvador, one of the largest sources of unauthorized immigrants crossing into the United States in recent years. (Last year, almost 50,000 of the roughly 304,000 people apprehended at the U.S. border were from El Salvador—a country of only 6.4 million.) There, I spoke with dozens of recent deportees from the United States, as well as others considering the trip for the first time. I also traveled to Chiapas, a key stop on the well-beaten Central American migrant path, to talk with dozens more travelers moving through the congested immigration hub.

To hear these men and women talk, it’s clear that, in a way, Trump’s policies are being received just as he expects them to be: Migrants seem to be more apprehensive about the journey than ever. But that doesn’t mean they’re staying home. Some, like Rosa, are choosing to leave their kids home and migrating without them. Some are moving through more dangerous routes if they do want to continue on to the United States—discarding the long-standing practice of turning themselves in to Border Patrol and applying for asylum. And in some cases, they are avoiding the United States: They’re deciding to settle in other countries, like Mexico or even Canada.

The picture that emerged, as I spoke to migrants and prospective migrants, is of a set of nations—from El Salvador and Honduras up through the United States and Canada—becoming even more entwined than they already are, with families further stretched and spread across borders. This might not be what Washington intended, but history shows that immigration is complex and hard to manage, and Trump’s policies are almost certain to have effects we haven’t begun to grasp.

Like Rosa Gonzalez, Roberto Quinones has learned to live with the uncertainty and instability of leaving his kids behind. (He also asked to use a pseudonym.) I met him on a September Friday in San Salvador, as he and 134 other deportees were unloading from a U.S.-funded plane from the States and boarding buses headed for the deportee reception center. There, they were shooed into an air-conditioned waiting room; given a number and their belongings, which were stuffed into mesh laundry bags labeled with the deportees’ names; and told to wait for their turn to be processed back into Salvadoran society.

Roberto had made the decision to go to the United States this past spring. This was after Trump had started cracking down on immigrants, but before the most visible height of the family separation policy. He had left his kids behind in El Salvador because of the dangers of the trail, and also because of shifting U.S. policies; under Trump, he figured, who knew what awaited him there?

In 2017, ICE deported more than 18,000 Salvadorans from the United States. Three times a week, a planeload of people—ranging from 60 to over 300—is deported from the United States to El Salvador. Approximately the same number arrive each week via bus from Mexico, which intercepts and deports migrants en route to the United States.

Roberto had left for the States four months earlier; it took him only a week or so to make it across the border, but he was apprehended almost immediately and was put in immigration detention, first in Texas, then in Chicago. He first heard the news about the government’s forcible separation of migrant children from their families in detention; he met another detainee whose child had been taken away by authorities at the border.

His reasons for leaving El Salvador are at once particular and astoundingly common. In his country, Roberto told me, the rules are clear: Ver, oir, callar—look, listen, keep your mouth shut. (This is a common Salvadoran refrain when explaining the gang regime.) To support himself while he was in school to be an accountant, Roberto drove a taxi. But his town—which he declined to name—was hot with gangs. Being a taxi driver shepherding people here and there at all hours of the day meant he’d seen and heard too much, which made him nervous.

He left taxi driving and started working in the family restaurant. But it didn’t take long for the gangs to find him there, and to start charging astronomical renta, or extortion payments, from a restaurant that was barely staying afloat. He got married and had a child; the gangs kept harassing him, so eventually he left for Panama, and then for Guatemala, where he worked banana harvests. “I was studying to be an accountant,” he said. “And there I was in Guatemala, loading huge crates of bananas on my back.” Meanwhile, the fact that he had left only made him more suspicious to the gangs, as if he had something to hide. When he was in Guatemala, his brother died; it wasn’t safe for Roberto to come home for the funeral. After that, he missed the birth of his second son.

Though its homicide rates have been decreasing over the past three years, El Salvador still has one of the highest murder rates in the world, with neighboring Honduras very close behind. These murders are, in large part, committed by the gangs. Salvadorans are routinely pressured into gangs and forced to pay renta—if they don’t, they risk being killed. Police and gang members are now in a perpetual standoff.

“I didn’t go to the U.S. at first because I knew how hard it was for immigrants there,” he said. But he couldn’t make a living in Guatemala or Panama, and at home he was sure he’d be killed. In the United States, even without papers, he’d be able to earn enough money to support his family—and do it in relative safety. “You can make $9 an hour there,” he told me. “Can you imagine?” He spent time trying to find the best, most trustworthy coyote—a human smuggler—but that put him out $9,000. He had only $4,000, his life savings, so he borrowed the rest.

Roberto’s wife and kids would pick him up from the reception center in San Salvador once he had been fully processed, but the family wouldn’t be going back home to their town that night. “No, no way,” he said. They would find a hotel in San Salvador. He couldn’t go back. He would spend some time sorting himself out—staying with church friends, or even inside the church itself for safety—and then he’d go again. (His $9,000 fee to the smugglers got him two tries, and then a discount on the third try. Since he was caught the first time, he has another shot without paying more—and it’s also in his coyote’s best interest to find a way to get him there without being caught.)

That night, once his number was called and he’d been processed—interviewed by the police and by immigration authorities, offered help finding jobs and a ride to the bus station—he’d finally get to see his kids. “What day is it?” he asked me, suddenly panicked. The sixth, I told him. He broke into a smile; his son was turning 2 in two days, and he’d be here for it.

I asked him directly whether Trump’s policies had had any effect on him—or would discourage anyone he knew from heading north. “I don’t think so,” he told me. “No, not at all.” When he was detained in Chicago, he saw the iconic cityscape, including the Chicago River, out the window as he was transported to detention. “I’d never imagined something so beautiful,” he said. But if he had his choice, he’d give up all that beauty and possibility just to be with his kids. Unfortunately, he doesn’t have that choice. “Better to see your kids every now and again than to never see them again,” he said, referring to the risk not of separation, but of being killed.

If Roberto finally makes it to the United States on his second or third try (and, he said, who knows—perhaps he’d try a fourth or fifth or sixth time, if he could scrape up the resources), he’ll work, pay off his debts and send money home to support his family. Perhaps he’ll send for his kids, but that depends on his circumstances and what’s happening in the United States. A long-term plan is a luxury of the certain.

One thing that has changed as a result of Trump’s policies, my interviews suggested, is the calculation of how, exactly, to cross the border.

Migrants face a decision: Do they try to slip across undetected by border authorities, or turn themselves in to claim asylum? For the past several years, the conventional wisdom among migrants from violence-torn Central America has been to turn themselves in and request asylum; coyotes have even instructed migrants to do so as a matter of strategy. After the Trump administration began criminally prosecuting those who asked for asylum after an illegal entry, some migrants chose to claim asylum in the legal way administration officials suggested: at official border crossings. But reports soon surfaced that migrants were getting turned away or told to wait.

Meanwhile, asylum policies are swiftly changing under Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who has deemed gang violence and domestic abuse—reasons many Central Americans are fleeing to the United States—largely insufficient grounds for asylum. The majority of U.S.-bound migrants I spoke to told me that they weren’t going to turn themselves in: Better, the information among migrants goes, to avoid the U.S. authorities altogether by finding a way across the border and making a run for it. (This change in strategy comports with the statistics: Researchers have found that harsher asylum policies do reduce the number of asylum applicants in the long run.)

The problem is that the places where people manage to cross undetected—where there are more limited patrols and as of yet no border fence—are among the most dangerous passages into the interior of the United States: high, dry mountainous areas, or sweltering desert passes in California, Texas and Arizona. In 2017, 412 migrants were found dead along the U.S.-Mexico border, an increase from the previous year’s 398—a figure more worrisome because migrant crossings overall were down in 2017 as Trump took office. These deaths, of course, only include those officially documented by federal authorities; many more could have been lost to the elements—swept away by the Rio Grande, eaten by animals, buried or their bodies not yet discovered.

Migrants are using their intel to take different routes through Mexico, too. According to Ruben Figueroa, a migrant rights advocate living in Chiapas, those migrants who are taking the journey alone without the help of a coyote, and who don’t want to apply for temporary transit paperwork in Mexico, are now crossing into Mexico through more remote territory on the gulf side of the Guatemalan border. They are also, increasingly, using sea routes, which makes the journey riskier. Migrants are often packed onto overloaded boats that travel far offshore to avoid detection.

Whatever gets them north, as quickly as possible and undetected. Whatever obstacles are put in their way, desperate migrants will find a way through—or around, or beneath.

But if the migration routes are becoming more complex and more dangerous, there’s also anecdotal evidence that the deterrence policy is working—not discouraging migrants from leaving, but rather diverting their paths away from the United States and instead settling in Mexico or even heading farther north to Canada.

A number of the Nicaraguans I met in Chiapas were taking this last tack, telling me they weren’t even trying for the United States. Sweeping civil unrest broke out in Nicaragua this past spring—not gang violence, as in El Salvador and Honduras, but the violent precursor to a more traditional civil war.

According to historical precedent, this would give them a relatively clear-cut asylum claim in the United States. But many Nicaraguans I met seemed skeptical of that option. “I can’t trust that your country can protect me,” a heavyset Nicaraguan father told me in the shade beneath a tree at Jesus el Buen Pastor, a shelter in Chiapas, amid the patter and shouts of little Salvadoran boys playing gangster. Pah pah pah pah pah pah, a 6-year-old shouted while staring down the barrel of a green plastic pipe. Under Trump, the man clarified, he felt it didn’t matter what his circumstances were; he was certain he’d be deported back home to the danger he’d left. Instead of settling in the United States, he was planning to cross through the country and into Canada.

Nearby, the little boys’ imagined assassination continued, and after a while, we all stopped our conversation and looked at them with some concern. Then the Nicaraguan father turned to me and, after a moment, asked, “Are you CIA?” I laughed, but he wasn’t kidding.

Later, I spoke with the little gunman’s mom: The boy had seen his father murdered right in front of him back home. Sometimes he would talk about what happened at the shelter, but his mom told him to hush. Who knows who’s around, she thought, who is listening, who might find out who they are? Under the new asylum policies, she would have only a slim chance of asylum, but she was heading for the United States all the same. She still saw it as the best option.

While the plan to pass through the United States to Canada is somewhat rare, over the past several years, more and more migrants are opting to stay in Mexico instead of continuing on to the United States, a choice becoming only more common in the wake of family separation. “Increasingly, Mexico is not just a country of transit or origin, but a destination country,” said Salva Lacruz, from the Tapachula office of the human rights and legal aid organization Fray Matias.

From 2013 through 2017, the number of asylum applications in Mexico increased by a factor of 11, from 1,300 to more than 14,000. Immigration experts and authorities like Mark Manly of the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees say that increasingly restrictive U.S. policies in recent years, coupled with increasing violence in Central America, drove the boom in asylum applications to Mexico. According to Lacruz, asylum applications in Mexico are likely to increase in the years to come, both because of increased enforcement at the U.S. border and because many Central Americans are now acting on their emigration plans after holding off on them while Trump took office, taking stock of what his new policies would mean for them.

Delmis Sarina Melendez and Jory Cartagena, parents of two children from the seaside city of La Ceiba, Honduras, are two people who have both applied for asylum to stay in Mexico rather than cross the U.S. border. Outside a shelter in Chiapas, they told me that they were headed for Tijuana, where Jory’s sister lives. They were waiting for their asylum paperwork so they could continue north, but they had outstayed their limits at not just this but at all the local shelters.

With everything they had seen on TV and heard on the radio about the children taken away from their families in the United States, they said, there was just no way they’d go there. “The sacrifices one makes to try to live in my country, and then after all that, to have to leave,” Delmis said, and trailed off. She’s pretty, with dark eyebrows and a wide smile, and was dressed in a red bandeau floral dress, as if she was at the beach rather than lingering outside a migrant shelter in a state of limbo. “Imagine, only leaving with just a suitcase, leaving everything, coming to a place where you know no one? And plus, with kids?” Her lip quivered as she spoke.

Staying in Mexico presents its own challenges. Many landlords in southern Mexico look down on Central Americans, or fear that they are connected to gangs, and won’t rent to them. Last week, Delmis said, they had sorted out an apartment they could afford while they waited for their asylum decision. They met the landlord, bags and children in tow. “Where are you from?” the woman asked them. When they told her they were from Honduras, she recanted. “Oh, no, I’m sorry, but no,” she said, “not after everything you people have done to my country,” and shooed them out. The xenophobia against Hondurans and Salvadorans, this mother told me, “is deep.” I’ve seen it and heard it, as well, during my time in Chiapas. “But at the same time, I understand her,” Delmis told me. “The same people she’s afraid of have ruined my country, too.”

The number of Central American asylum seekers hasn’t risen only in Mexico, but also in neighboring countries. In Panama, Costa Rica and Belize, the number of asylum-seekers from Northern Triangle countries—Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala—rose to 4,300 in 2016.

Some of the migrants I met didn’t have plans to stay in Mexico long term but were there to apply for a humanitarian visa—a visa that will buy a limited amount of time in Mexico without being deported. Some will apply to stay in Mexico forever, but many will use the time to organize themselves for their more-than-1,000-mile journey up to the northern border—to earn some money, figure out the safest route, perhaps even hire a guide or buy a plane ticket, since the roads are so dangerous. Migrants have figured out that with this temporary Mexican visa, they can’t be arrested by the authorities en route to the United States and deported back home to danger—though they can still be harassed, extorted and bribed. It can take a few weeks or months to get the humanitarian visa processed; in the meantime, the people wait in and around Tapachula.

Starting around 3 a.m., on a side street with a hill sloping down toward a river outside the offices of COMAR, the government agency that processes asylum paperwork, the line for these visas began to form. Migrants got up from wherever they were sleeping—in the city park, in a shelter, in an apartment they were lucky enough to manage to rent—and posted up on the sidewalk until the sun rose and the office building opened, like waiting for concert tickets or in a bread line.

Imelda Lima, a mother of two in her 30s, and her friend Zhully Alfaro, whom she’d met in Tapachula, surveyed the line. (They also asked me to withhold their real names, out of fear of people from their hometowns finding them.) Imelda was in the line with her two daughters, ages 6 and 10.

Zhully pulled out her cellphone and opened to her photographs, then showed me a photo of a young man, dead and lying in a pool of blood on a crude tile floor, a bullet hole in his head. “That’s my nephew,” she said. “They tortured him, then they killed him,” she said, referring to the gang that ruled in her hometown in Honduras. They’d later sent the photos as a threat. It was unclear to Zhully why the young man was targeted, but his murder went largely uninvestigated: a relatively typical case in Honduras, where impunity reigns and police sometimes lack the vehicles or fuel needed to get to crime scenes at all. She gave me his name. “Look him up,” she told me, so I could be sure she wasn’t lying. I didn’t think she was lying, but later I did look him up: a 25-year-old man, murdered, stripped, left for dead. He had no identification on him when he’d been found, and the morgue brought him in as an unknown.

In Imelda’s neighborhood in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, the North American gang called Barrio 18 was king. Members patrolled the streets, monitored people’s comings and goings, and charged renta to individuals and businesses, sometimes all but bleeding them dry. As has long been the case with gangs in Central America, to get on the wrong side of Barrio 18—not paying your renta, crossing a gang member, declining to join the gang or to become a gang member’s girlfriend—was to risk death, rape or dismemberment. The local Barrio 18 boys, many emblazoned with tattoos to mark their membership, commandeered her house for their operations; they came over one day and told her to leave.

Imelda and her daughters fled, and for the moment, they were living with a woman in Tapachula who gave them food and shelter in exchange for help around the house. It’s a generous arrangement, Imelda said, but it was sure not to last long. And, she said, they don’t feel safe, even here. Just the previous Friday, Imelda told me, she saw a guy with “18” tattooed on his forehead, right here in Tapachula. “I was running from them in my country and now they are here?” she said.

The night before, as they waited in the visa line, it had been drizzling; she laid her daughters on the sidewalk, covered them with their jackets and held an umbrella over them so they could sleep without getting too wet. Eventually, some guys ahead of them in line took pity on them and gave them their makeshift tarp to lie on—just a ripped-up, sturdy green bulk dogfood bag with an image of a well-groomed pooch and a smiling, light-skinned lady.

At the time I spoke with her, Imelda was planning on staying in Mexico, but the possibilities were open. Once she got papers, she’d try going farther north in Mexico to find work and a more stable situation. She couldn’t bear the thought of being separated from her kids. But if she couldn’t make it in Mexico—or if her life was threatened again—she could be forced to try her luck in the United States, and risk having her children taken away from her.

By the time I was back home in California, Imelda messaged me to say she was moving into the shelter on the other side of town in Tapachula. “I know that God will help us forward,” she wrote.

In El Salvador, away from the steady, determined march of migrants through southern Mexico, I knew there was a crucial piece of the story that I had to seek out. Was anyone actually doing what Trump suggested and just staying home?

Given that most people in El Salvador are fleeing violent criminals, hardly anyone is open about their thought process before they leave. As a result, it was difficult to find anyone admitting that they were close to leaving and then decided against it. Despite these difficulties, I did find one person who was deterred.

I was introduced to Arnovis Guidos Portillo through the photographer with whom I worked for this story, Jose, who lives in El Salvador. Arnovis, a 26-year-old man living on the country’s coast, had his 7-year-old daughter, Meybelin, taken away from him at the U.S. border this past spring.

By the time I met him, Arnovis had already become something of a news figure: At the height of the family separation news blitz, he had been featured in the Washington Post and the Guardian, and was spotlighted in a PBS “Frontline” episode on family separation at the border. His story was a particularly extreme one, and he’d been willing to talk to the press.

He’d crossed into the United States with Meybelin, his brother-in-law and his brother-in-law’s 6-year-old daughter. All four were separated into different facilities; Arnovis told me he nearly lost his mind. Nearly a month went by in detention without Arnovis hearing anything about his daughter, her whereabouts, whether she was safe or even alive. When ICE officials pressed him to sign the paperwork agreeing to his own deportation, he said he wouldn’t sign unless it guaranteed he would be reunited with Meybelin. They told them that if he signed the papers, he’d get his daughter back and could go home. But when he was shepherded onto the plane in Texas headed back to El Salvador, there was no Meybelin. “I told you not to fail,” his mother said to him when he came back to El Salvador empty-handed, his daughter stuck up north. After a long legal battle, Meybelin was eventually sent back to El Salvador.

Arnovis had fled El Salvador because of problems with gangs; now that he was back, the stories about him made him higher profile in his town, and this was not a good thing. The way he saw it, the gangs believed journalists were paying him for his story, making him an even bigger target.

Originally, Arnovis was planning on heading back to the United States. There was no life for him in El Salvador with gang members wanting him dead. It was exceedingly difficult for him to find work; the Salvadoran economy was stagnant, and he had to move in secret lest he be recognized by one of the gangs. He had also come under investigation by Salvadoran authorities for endangering his child on the way north to the United States, a rare circumstance, given how many families send their children north each year. He felt under assault from all sides.

When we spoke, Arnovis had decided he couldn’t go to the United States again illegally—certainly not with Meybelin, after everything the U.S. government had done to tear them apart. But he also wasn’t sure he could try it on his own. He couldn’t bear the thought of being apart from his daughter again or another spell in detention. The lawyers from RAICES, a legal organization in Texas, that helped get Meybelin out of detention and back to El Salvador, were seeing whether they could apply for asylum paperwork for Arnovis. For now, he said, he was waiting.

The Trump administration’s deterrence plan centered on the idea that it could make an example out of separated families. If one family separated at the border could discourage thousands from making the same trip, the policy could have been an effective deterrent, at least, if still objectionable on humanitarian grounds. But in the one case I found, that ratio was 1 to 1. The one family I talked to who had experienced the policy was the same family deciding, for now, to stay put.

Elsewhere, the northward ambitions of Roberto and Rosa were still underway, creating new families split by borders. Arnovis wasn’t ready to leave his daughter again, so he was stuck in El Salvador, worried for his life. For now, he would wait for a miracle: papers, some kind of legal pathway out of the country. And he still had a destination in mind. Despite everything, he was still hoping to end up in the United States.