Top financial managers at Boys Town have earned more than most peers working at the country's largest nonprofits.

Two men who have long managed Boys Town's vast investments, including its separate nonprofit endowment holding more than $1.1 billion in assets, have been paid generous salaries as employees by the nonprofit and also as subcontractors through their own private investment firm.

Compensation for Phil Ruden, chief investment officer at Boys Town and executive vice president of its endowment, and Michael Eglseder, former vice president of investments and treasurer of the endowment fund, already exceeded that of many of their peers in the nonprofit world before Boys Town's endowment paid their private firm, Prodigy Asset Management of Omaha, Nebraska, as a subcontractor in 2021, according to an annual compensation report provided by Candid, formerly called Guidestar.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund critical stories in local U.S. newsrooms. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

In 2020, the compensation package of Ruden, a Boys Town employee for at least 41 years, for his work at Boys Town and on behalf of the endowment totaled $751,657. Eglseder's was $628,259, tax returns show.

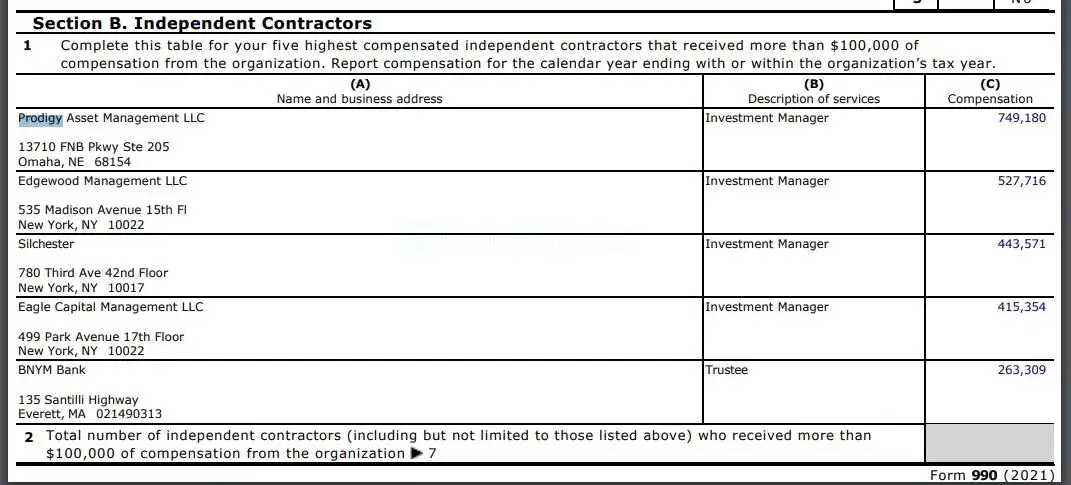

In 2021, Boys Town lowered the two men's salaries, but made a separate $750,000 payment to Prodigy, where Ruden and Eglseder are cofounders and managing partners, according to the company's website.

Ruden was paid $460,327 by Boys Town in 2021. Eglseder earned about $200,000 before he left Boys Town in April 2021, according to the last publicly available tax return of the endowment, called Father Flanagan's Fund for Needy Children.

The combined decline in compensation for both Ruden and Eglseder from 2020 to 2021 was about $720,000. But the payment to Prodigy Asset Management exceeded their losses by $30,000. The 2021 tax filing was the most recent publicly available. The Register requested tax forms from 2022, but Boys Town did not respond.

The nonprofit also did not respond to a request for comment and explanation. Nor did Ruden and Eglseder.

Boys Town is a multifaceted nonprofit that has programs and services that span human services, health care, research and education. According to its tax filings, decisions about executive compensation at Boys Town are made by a subcommittee of its board of trustees and include comparisons with similarly qualified people in similar jobs. It's unclear what comparisons Boys Town used.

Other than its tax forms, however, little has been made public about Father Flanagan's Fund for Needy Children, an endowment that holds most of the nonprofit's fortune and distributes grants of about $46 million annually to the landmark home in Nebraska that includes 50 family-style foster homes on the Boys Town campus west of Omaha.

The fund is not analyzed or rated by most charity watchdogs. In 2021, its board was made up entirely of Boys Town insiders: CEO Rod Kempkes, the Rev. Steven Boes, Chief Financial Officer Judy Rasmussen, Ruden, Eglseder and other top executives.

In 2021, three New York investment firms and one Massachusetts bank, BNY Melon in Everett, also were listed as subcontractors, for a total cost of $1.65 million to manage the endowment's portfolio.

Ruden and Eglseder, meanwhile, made more than peers at some of the largest high-asset charities in the U.S. In 2021, Brian Rhoa, the chief financial officer of the American Red Cross, which has $3.9 billion in assets, earned compensation of $594,976. Mark Sutton, chief financial officer of United Way Worldwide, earned $348,681. The treasurer for Feeding America, the No. 1 charity on Forbes' 2022 list of the top 100 charities based on annual fundraising, received a total of $435,180, tax records show.

Median executive compensation at the largest nonprofit organizations in the country — those with annual revenues of more than $50 million — was $293,000, based on 2021 figures, the most recent available to Candid, which publishes a compensation report annually. Executives in the Midwest tend to earn the least, with a median income of $111,000, according to Candid, the nonprofit tracker formerly known as Guidestar.

A nonprofit can do business with an insider, but its board has to take certain precautions to make sure the transaction is in the nonprofit's best interest.

Gordon Fischer, an Iowa City attorney with expertise in nonprofits, said there are ways nonprofits can pay leaders as subcontractors, "but it is very out of line ethically."

Since 1969, the IRS has had prohibitions for 501(c)(3) charities against self-dealing, forbidding anyone with substantial influence over a charitable organization, including members of the board of directors and employees who manage the organization, from benefiting excessively from the organization beyond salary or wages.

The IRS has said compensation that is "reasonable and necessary to carrying out the exempt purpose of the private foundation shall not be considered an act of self-dealing if it is not excessive."

The tax form has a specific place where a nonprofit is supposed to indicate "yes" if it engaged in "an excess benefit transaction" with a "disqualified person" who directs or manages the organization.

An excess benefit transaction, according to the IRS, is a transaction in which an economic benefit is provided by the tax-exempt organization, directly or indirectly, to or for the use of a disqualified person, and the value of the economic benefit provided by the organization exceeds the value of the consideration received by the organization.

That box was checked "no" on the Father Flanagan's Fund for Needy Children tax form, and the form does not disclose Ruden and Eglseder were partners in Prodigy. It does say Ruden and Eglseder had a business relationship with the fund.

The IRS is prohibited from commenting on any specific taxpayer or entity. Experts on nonprofits said charitable organizations are required to disclose excess benefit transactions on their tax forms to avoid the appearance of self-dealing.

According to Prodigy's website, Ruden and Eglseder created their private investment firm in 1993, while they were working at Boys Town. It's unclear what work Prodigy did for the endowment at a time when Boys Town was already paying both men to manage its investments. It's also unclear how they divided their time between the two entities.

Ruden has run Boys Town's investment program since 1986. According to Prodigy's website, he also restructured Boys Town's portfolio and is an expert in hedge funds and private equity.

"The first thing the IRS looks at is, are there any checks going back to board members? Because that's self-dealing," said Jeri Holmes, an Edmond, Oklahoma, attorney who has worked with nonprofits for 20 years.

Reviewing the endowment and Boys Town's 990 tax forms, Beth Gazley, a faculty member at the Paul H. O'Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University and a Ph.D. who has done research on nonprofits for decades, said she didn't see any explanation of how Prodigy was selected as an investment manager.

"They can’t make their own compensation decisions. All compensation has to be reported somewhere. If they own Prodigy that is also being compensated," she said. "If (Ruden and Eglseder) are owners in that company, I think the only way this might work for the IRS or attorney general is if they can prove that they aren’t disqualified people."

The most important principle for the public in evaluating nonprofits is transparency for the donor, Gazley said. But increasingly organizations have spinoff organizations, public and private, that can mask the greater picture.

If the public doesn't know about separate nonprofits or related businesses, the public doesn't see the whole picture, and that makes assessing a nonprofit like Boys Town difficult, she said.

"Are they deceiving people? That’s a stretch," she said. "But are they being as transparent with donors as they could be? That‘s a fair question to be posing to them."