For two weeks in February, Seoul’s downtown streets were awash with right-wing protesters opposing the government’s efforts to reconcile with North Korea. The marchers, mostly middle-aged and older, clutched bullhorns and balloons and waved South Korean flags. One banner, done up in a style typical of Korean funerals, mocked the South Korean president, saying that with liberal Moon Jae-in in charge, “reunification with communists is no problem.” A few even carried large posters supporting his recently impeached predecessor, who still has a small cultish following in the country. The protesters clogged the downtown area during rush hour and even attempted, albeit unsuccessfully, to block the motorcade carrying North Korea’s delegation to the closing ceremonies for the Olympics.

The overwhelming majority of South Koreans are skeptical about prospects for peace with Pyongyang, but it’s South Korea’s hard right, a small minority of the population, that is leading the opposition to the government’s outreach to North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. They are highly mobilized and—not unlike America’s own conservatives during the Obama years—in something of a chrysalis. What exactly will emerge on the other side is unclear.

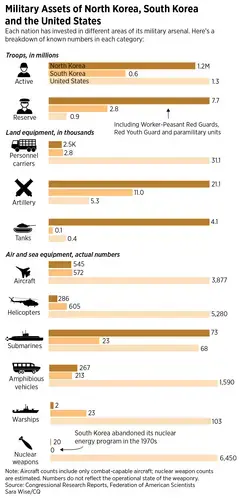

What is apparent, however, is that the evolution of South Korea’s conservatives will profoundly affect the future of the U.S. alliance, the country’s prospects for pursuing a nuclear weapon and the stability of the entire East Asia region. To protect the country from Kim’s nuclear arsenal, South Korean conservatives are campaigning for the return of U.S. short-range nuclear weapons that the United States withdrew from the peninsula in the early 1990s. The only other alternative, some in the hardright camp argue, is for South Korea to develop its own nuclear bomb.

“We have to do either one of them in order to maintain our dignity as a nation,” argues Cheon Seongwhun, a former national security adviser to President Park Geun-hye, who was impeached in late 2016. Either option would undoubtedly make it more difficult for the United States to navigate the tangled web of potential security disasters in East Asia. All the more reason, argue South Korean analysts, for Washington policymakers to start paying active attention to what is developing beneath the radar in Seoul.

Were South Korea to pursue a nuclear weapon, it would have cascading negative effects for the United States and the global nonproliferation order, which is already teetering. There is strong reason to believe that Japan, which has its own security concerns regarding North Korea, would be tempted to acquire its own nuclear weapon. Japan, which already produces nuclear fuel, would have a jump-start on a nuclear weapons program. It could spur Taiwan, another advanced nuclear state in East Asia that Beijing claims as its territory, to get its own nuke.

“China will raise hell,” Andrei Lankov, director of the Korea Risk Group, says over cups of sweetened tea in his cluttered office at Kookmin University, where he teaches. “For China, it will be seen as a life-and-death issue. They will stop at nothing.”

North Korea’s nuclear weapons are already an enormous security concern for the United States. An East Asia where South Korea, Japan and even Taiwan all have nuclear arsenals that are aimed at North Korea and China, with missiles pointing right back at them from Beijing, would be a much greater nuclear nightmare than anything seen during the dark days of the Cold War.

President Moon, a onetime activist and former human rights lawyer, enjoys strong approval ratings and his ruling Democratic Party is expected to do well in local elections this June. But Moon, who was swept into office in a special election in 2017 on a tide of public disgust with his conservative predecessor’s corruption, has embarked on a high-risk, high-reward foreign and domestic agenda. If things go badly for Moon over the next few years, particularly on the North Korea front, it likely won’t be long before conservatives are back in power, a position they have occupied for most of South Korea’s 70-year history.

Moon backs President Donald Trump’s planned spring summit with Kim. But there are many risks for South Korea. Trump, an inexperienced nuclear negotiator with little interest in or patience for wonky policy details, could rush to make a deal with Kim that would destabilize South Korea and the alliance. Trump could strike a deal, for instance, that would halt North Korea’s work on a nuclear intercontinental ballistic missile targeting the United States but leave the rest of Pyongyang’s weapons programs intact, including the shorter-range ballistic missiles that could strike South Korea and Japan.

Contrary to both Moon and Trump’s optimism about the prospects for a diplomatic breakthrough with Pyongyang, Cheon and most South Korean conservatives see “zero possibility” that Kim Jong Un would give up his nuclear weapon capabilities.

Chronic Insecurity

Most South Koreans say they would support their country developing a nuclear weapon. And more and more independent South Korean strategists worry about the reliability of U.S. security guarantees now that North Korea is on the verge of an ICBM. These voices are expected to only grow louder and stronger, particularly as Seoul questions the United States’ commitment to its security.

Trump cast doubt on the countries’ relationship in a March fundraising speech, when he implied the United States would withdraw some of its troops from the Korean Peninsula if South Korea didn’t give him what he wanted on the trade relations front.

“We have a very big trade deficit with them, and we protect them,” Trump said, according to a Washington Post report. “We have right now 32,000 soldiers on the border between North and South Korea. Let’s see what happens.”

Though trade has complicated the bilateral relationship before, Trump is the first U.S. leader to explicitly link economics with the security alliance. His comments are deeply disturbing inside South Korea, where even longtime experts of the U.S.-South Korea alliance quietly and anxiously confided that they don’t know what to make of the political events happening inside the United States.

Kim Hyun-wook, a professor of American Studies at the Korea National Diplomatic Academy, a government-run school that trains South Korea’s diplomats, says it is Trump’s “America First” trade policies that are the biggest threat to the alliance.

Comments by other senior U.S. officials like CIA Director Mike Pompeo, now Trump’s pick to lead the State Department, and former National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster have many in South Korea wondering. Inside Seoul, officials and experts see Trump’s new National Security Adviser John Bolton as even more problematic. In a March interview with Fox News, the combative former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations derided the South Koreans as “like putty in North Korea’s hands.”

Senate Armed Services member Lindsey Graham of South Carolina last year told NBC News, “If there’s going to be a war to stop [Kim Jong Un], it will be over there. If thousands die, they’re going to die over there. They’re not going to die here.” The famously unreserved Republican hawk followed up those comments by telling CNN in March that “all the damage that would come from a war would be worth it, in terms of long-term stability and national security.

While Kim Ji-yoon, who leads the right-leaning Seoul-based Asan Institute’s polling research, says she doesn’t think the Trump administration would actually initiate a limited strike on North Korea—which the overwhelming majority of experts agree would escalate into a full-blown war with a death toll not seen since the days of World War II—she doesn’t understand why Graham and other top U.S. officials have made so many careless remarks about South Korea’s security.

“What Korean people hate most is being neglected or being taken for granted,” Kim says. “It’s hard to explain in English, but it’s a really sensitive feeling that you basically want to be recognized as an important ally.”

But even if Trump and lawmakers like Graham weren’t making troubling remarks, South Korea likely would still be plagued by insecurity—as it has throughout its decades-long security relationship with the United States.

Decades of Stress

In the early 1970s under the direction of South Korean dictator Gen. Park Chung-hee—the father of Park Geun-hye—South Korean scientists began developing a nuclear weapons program. At the same time, South Korea and the United States were negotiating terms for the continued deployment of U.S. forces in the South with Washington eager to draw down its presence and reduce its security assistance, which Park opposed.

The Ford administration learned about the nuclear program in 1974, according to a recently declassified State Department report. Over the ensuing years, Washington worked both to shut down the channels providing South Korea with its nuclear weapons technology and threatened to pull its military and economic support if the weapons work continued. President Jimmy Carter took a different tactic in 1978 when he backed off a pledge to withdraw U.S. troops. Park finally shut down the official program. Still, secret nuclear weapons-relevant experiments took place in the early 1980s.

That history offers useful lessons today about what really motivates South Korea’s major defense decisions—and also what kinds of threats and inducements can keep Seoul tethered to the United States.

There are also significant parallels to nuclear development in Europe in the 1950s.

Though Washington tried using security guarantees to talk London and Paris out of developing their own independent deterrents, the Soviet Union’s then-conventional military advantage over Europe, plus its rapid advances in nuclear and missile testing, were ultimately too unnerving.

“We are exactly following the same path that Western Europe took 50, 60 years ago,” says Cheon Seongwhun, the former adviser to President Park. He leans forward and speaks urgently throughout an hour-long interview because, he says, he feels passionately about the United States understanding South Korea.

“What Korean people hate most is being neglected or being taken for granted.”

Cheon doesn’t want South Korea to get its own nuclear weapon, but he thinks the United States should be more sympathetic to the security situation in Seoul, noting that North Korea represents a much more direct threat to the South than the Soviet Union ever did to Western Europe.

But the United States traditionally has resisted giving South Korea the type of explicit security guarantees officials there have sought. In alliance talks on U.S. extended deterrence, which includes nuclear weapons, ballistic missile defense and conventional military capabilities, Obama administration officials “always refused to get into specific discussions” about the circumstances under which the United States would use its nuclear weapons to defend South Korea, says Choi Kang, vice president of the Asan Institute and a former South Korean government defense strategist.

The United States, Choi says, has never provided details, saying only that any decision to use nuclear weapons is the exclusive domain of the U.S. president.

That hasn’t sat well in South Korea, where officials wonder if Trump or a future U.S. president would hesitate to use nuclear weapons to protect the South. And so, for those South Koreans who believe that the bomb is the ultimate form of deterrence, being under the U.S. nuclear umbrella doesn’t feel quite as secure as it once did.

Nurturing Process

As a former deputy assistant secretary of Defense for East Asia during the Obama administration’s final years, Abraham Denmark took part in multiple alliance meetings with South Koreans on U.S. extended deterrence.

“I participated in these conversations a lot and understood where our South Korean allies were coming from,” says Denmark, now with the Woodrow Wilson Center. “Their security is dependent upon another country and it makes perfect sense that they would seek that reassurance.”

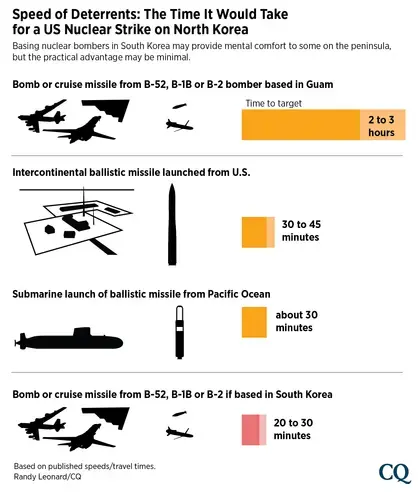

Denmark says the United States tried to give South Koreans more confidence, including issuing regular statements on the health of the extended deterrence options, increasing the number of deployments of strategic bombers to the Korean Peninsula and Guam, and bringing South Korean delegations to the United States for tours of key U.S. nuclear weapon sites.

But it never seemed to be enough for the Park government. “We tried to do a lot and our Korean allies were always trying to figure out new ways to explore this issue,” he says.

The problem, as U.S. and South Korean experts explain it, is that South Koreans need increasingly stronger and stronger reassurances from the United States. What worked a few years ago is no longer good enough, and even if the United States were to grant some conservatives their wish and redeploy tactical nuclear weapons to the peninsula, it wouldn’t be long before the South Koreans would start calling for something else, like the permanent home-porting of a U.S. ballistic missile submarine at the Busan Naval Base.

For now, the Moon government says it feels good about the strength of the U.S. alliance, despite concerns last year and even as recently as January that Washington would ignore Seoul’s wishes and carry out a limited attack on North Korea to halt its ICBM progress.

Kim Kyung-hyup, a member of Moon’s party who serves as vice chair of the Foreign Affairs and Unification Committee in the Korean National Assembly, laughed and shook his head when a CQ reporter pressed him for his honest opinion about Trump.

Speaking through a translator, Kim says he disregards Trump’s flippant remarks and pays attention instead to the formal statements the U.S. government issues about the relationship with South Korea, which are largely in line with decades of bipartisan foreign policy toward Seoul, as well as the feedback and information received from the Pentagon and State Department, which is also mostly unchanged since the Obama administration. “All of those multi-channel supporting centers can prevent spontaneous decisions of Donald Trump,” he says.

Going Nuclear

In the ongoing debate over the future of South Korea’s national security strategy, it is emotional arguments, not logical ones, that are likely to have the most salience.

South Korean conservatives, including Hong Joonpyo, current chairman of the main opposition Liberty Korea party, have seized on the nuclear weapons issue to distinguish themselves from Moon and his liberal government.

If the Moon administration bungles the North Korea issue, as previous liberal governments have done with their own failed “sunshine” policies of aid-for-denuclearization, South Korean conservatives could be elected back into power, as most experts agree is eventually inevitable.

Traditionally, about 40 percent of South Koreans are conservative and 25 percent to 30 percent are liberal, according to Kim Ji-yoon, the polling expert.

“They will resurrect and [South] Korea will still be a conservative country, thanks to North Korea,” she predicts.

Just as Republicans were hardened during the Obama years, reacting to what they viewed as dangerous liberal overreach in both the domestic and foreign policy realms, South Korean conservatives are trying out various policy arguments against Moon as he embarks on a risky diplomacy push with Pyongyang. But it’s the organized and mobilized hard right and not the moderate conservatives in Seoul who have the microphone right now.

South Korea has never had the historical aversion to nuclear weapons that neighboring Japan has had. For decades, South Korea was pronuclear, viewing the United States’ use of the atomic bomb in the final days of World War II as the thing that finally freed the Korean Peninsula from the yoke of Japanese colonization. It’s only in the last few decades, and particularly under the influence of the Obama administration, that the language of nuclear nonproliferation and nuclear security became a common public value, experts say.

Traditionally, security issues such as North Korea and the U.S. alliance affect South Koreans’ voting decisions more than comparable defense matters do for American voters, says Woo Jeong-yeop, a polling expert with the conservative Sejong Institute.

During an interview at his organization’s spacious offices on the outskirts of Seoul, he notes that even some South Korean liberals are open to a domestic nuclear weapon because they view it as a sovereignty issue and a way to wean themselves off relying on the United States for their defense. Historically, South Korean conservatives have been much more pro-United States than liberals.

Support for “South Korea’s nuclearization” has slowly ticked up from almost 56 percent in 2010 to nearly 65 percent in 2016, according to Asan Institute polling. Both pronuclear and anti-nuclear analysts agree, however, that support is mostly lukewarm, with the hard right being the most fervent nuclear backers.

Conservatives argue this latent support could be “catalyzed” into an active political movement if the North Korean nuclear crisis worsens and public doubts grow about the reliability of the U.S. security umbrella.

On the other hand, liberals say the existing tepid support would likely fade if South Koreans were better informed of all the economic, diplomatic and security tradeoffs the country would make in order to secure either a U.S. tactical nuclear weapon deployment or, and even more so, an independent atomic arsenal.

Still, the most notable increase of support for some sort of nuclear weapons option has been found within South Korea’s elites, including a small number of liberal academics. And as South Korea—unlike the United States—has a largely top-down political culture, the views of the party leadership are largely adopted by the rank-and-file.

“More and more people in the opposition party subscribe themselves toward indigenous nuclear capability,” says Choi. “That’s a big change.”

The principal opposition party Liberty Korea has yet to take an official position on South Korea having an indigenous nuclear weapons program and is focusing its efforts instead on trying to rally public support for the redeployment of U.S. gravity bombs. But if the United States refuses to listen to these calls, then the party would be open to pursuing a nuclear weapon with the goal of achieving parity with North Korea, says Jeong Nak-keun, the chief researcher for security studies at the Yeouido Institute, which is affiliated with Liberty Korea.

Duyeon Kim, a senior research fellow with the Korean Peninsula Future Forum who has done considerable research on whether South Korea will try to acquire a nuclear weapon, says it’s likely the country’s pro-nuclear voices will be increasingly empowered if the United States tries only to contain—rather than dismantle—North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

Considering Kim Jong Un’s nuclear fervor, it’s hard to see how the “go nuclear” argument does not gain more support in South Korea. Lee Jung-hoon, professor of international relations at Yonsei University and an adviser to the South Korean Foreign Ministry, predicts that Pyongyang’s behavior toward South Korea will likely grow more belligerent and coercive once it views itself as a “genuine, bonafide nuclear power.”

“Can you imagine … ?” Lee asks, a note of incredulity rising in his otherwise carefully modulated voice, as he conjures the prospect of a North Korea confident that its nuclear powers have made it untouchable — not the least against South Korea. Such a future would be “extremely difficult” for South Korea to tolerate, he says. “If not, then something is wrong with us.”

What to Do

While U.S. lawmakers are laser-focused on the North Korea danger and the potential for Trump to begin a war with Pyongyang, only a few, like Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Edward J. Markey, are paying much attention to South Korea’s latent nuclear proliferation potential.

There is no quick and easy solution, but Washington policymakers are not without options to respond to the evolving security situation in South Korea. Despite its liberal government, giving short-shrift to South Korea’s pro-nuclear arguments, as was possible during the Obama years, is no longer feasible, analysts agree.

There is an argument to be made that redeploying U.S. tactical nuclear weapons would be a good deal better than allowing South Korea to develop a nuclear weapon, with the potential domino effects that would cause in Japan and Taiwan. But that scenario is still years away, in large part because the Moon government has little interest in such a hawkish response to Pyongyang.

The nuclear issue in South Korea could come to a head in 2022 if the country elects a pro-nuclear conservative president, giving the United States four years to mollify South Korea’s security concerns.

Denmark says the U.S. should not put itself in a position where it feels like it has no choice but to redeploy nuclear weapons to the South. “My sense is there are a lot of steps between here and there and the U.S. should be proactive about pursuing them,” he says.

Those steps include significantly increasing the amount of time U.S. ballistic missile submarines and heavy bombers spend in the Western Pacific, a move that would send a strong message to both China and North Korea about the United States’ commitment to South Korea. The United States could also create a consultative body similar to NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group where nuclear policy, planning, doctrine, operations and incidence management can be discussed in greater detail with Seoul, according to a December policy brief written for 38 North by Richard Sokolsky, a former longtime official with the State Department’s prestigious Office of Policy Planning.

“We are at a threshold of North Korea becoming a genuine nuclear state and that is a whole new ballgame than what we’ve been dealing with in the past,” says Lee Jung-hoon of Yonsei. “Are we ready for that? Not the way we’ve been responding, no. So we need change, a new approach.”

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Rachel Oswald

As the United States and South Korea search for a way to resolve the North Korean nuclear weapons...