Editor's note: Saudi Arabia's religious landscape has sometimes appeared as a monochromatic terrain of pious Muslims following an intolerant, puritanical version of Islam. If that picture was ever accurate, it is certainly not today.

Saudi Arabia is in the midst of a slow but major social transformation in part because its largest-ever "youth bulge" is reaching adulthood. This transformation involves changes in the religious attitudes of ordinary people as well as shifts in the relationship between the House of Saud and its official religious establishment. The time when the state could use religion — instead of bald repression — to enforce uniform social behavior and impede political action has passed.

This is Part One of a five-part series to be published in the coming days.

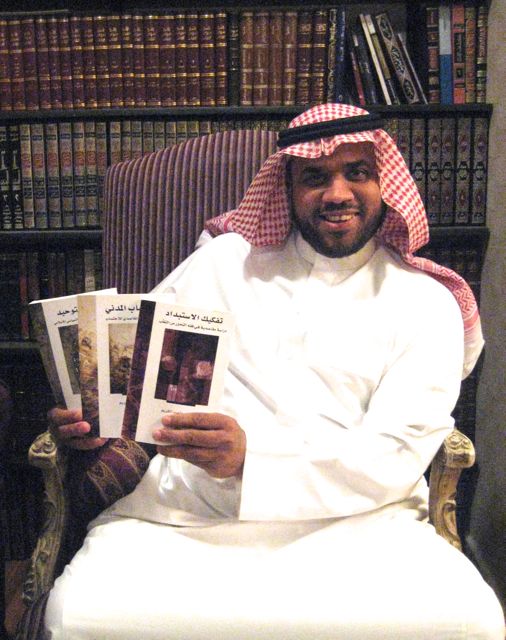

RIYADH, Saudi Arabia — When Hamza Al Salem was in his 20s, he could recite the Quran from memory, wanted banks shut down because Islam bans the charging of interest and vowed to avoid non-Muslim countries when he traveled.

"I was a very pure, fundamental Wahhabi," said Al Salem, whose university-level religious studies were in the ultraconservative Wahhabi approach to Islam named after the 18th-century Islamic reformer Muhammad bin Abd AlWahhab.

Today, Al Salem, 48, is a public critic of how Wahhabism, the kingdom's official version of Islam, is practiced and of the role played by its clerics who have considerable sway over the kingdom's public sphere, enforcing strict gender segregation through the religious police, and inhibiting many forms of recreation, such as cinemas. Their anti-intellectual, ultra-orthodox version of Islam also acts to dampen Saudi creativity and impede government modernization programs.

Al Salem does not want to abandon Wahhabism, he explained in an interview in his Riyadh home. Rather, he wants to bring it to fruition so that it reflects the Islam he believes was proclaimed by Prophet Muhammad.

For Al Salem, that means an Islam that puts no intermediaries between a Muslim and God, leaves Muslims free to make their own moral judgements about right and wrong and that treats 14 centuries of Islamic legal rulings as guides, not obligations to be slavishly imitated.

"I always say Wahhabi thinking is excellent," said Al Salem. "It's exactly the way Prophet Muhammad wants Muslims to be."

But Al Salem contends that the kingdom's official religious establishment has not applied it correctly.

"If they can prevent anything new, they'll prevent it," he said. "And that comes from their way of thinking and of just repeating old fatwas [religious rulings]."

Al Salem is an example of the critique that is percolating — sometimes above the radar, sometimes below — in Saudi Arabia's religious landscape. He is one of the Saudi religious and intellectual figures challenging Wahhabism, or how it is applied.

Their critiques are not all the same. Some are politically oriented, others more theological. Some write books; others tweet. And they mostly are solitary voices with little or no contact with each other.

Besides Al Salem, other contemporary critics include assistant professor of Islamic jurisprudence Mohammed AbdulKareem, novelist Turki Al Hamad and writer Abdullah Al Maliki.

They are not pioneers. After the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, perpetrated mostly by Saudis, and Al Qaeda's violent insurgency in Saudi Arabia from 2003-2006, many Saudis openly called for religious reform and charged that Wahhabi teachings were fostering extremism.

Historian Hasan Al Maliki, for example, charged in his books that negative portrayals of non-Muslims in Wahhabi-influenced school curricula was fostering extremism. And in 2007, writer Mansour al Nogaidan opined in the Washington Post that "Islam needs a Reformation...It's time to accept that God loves the faithful of all religions...and to call for a bold renewal of our faith as a faith of goodwill, of peace and of light."

Stephane Lacroix of Sciences Po in Paris, an expert on the kingdom's religious scene, has written about the coalition of liberals and Islamists who began demanding political reforms in the late 1990s "while expressing unprecedented criticism of the Wahhabi religious orthodoxy."

In addition to historian Al Maliki and writer Al Nogaidan, this coalition included Wahhabism critics such as former judge Abdelaziz Al Qasim and literature-professor-turned-political-activist Abdullah Al Hamid.

Their efforts culminated in a detailed petition sent to then-Crown Prince Abdullah Abdulaziz in 2003 that called for political reforms including elections, the rule of law, freedom of speech and assembly.

When he became king two years later, Abdullah ignored these political demands. However, he launched reforms in education, sent thousands of Saudis overseas to study, loosened restrictions on the press, partially reined in the religious police, and began allowing women a greater role in the workplace and public life.

These moves were unpopular with many clerics, who also did not like seeing their king meeting with Pope Benedict XVI in 2007 and hosting an international interfaith conference in Spain.

As a result, Abdullah's royal court mostly ignored the standard bearers of Wahhabism, whether independent clerics or those employed by the state. These religious authorities also have lost credibility in recent years, especially among young Saudis, who say their religious rulings, or fatwas, are not grounded in real life.

"Criticism of Wahhabism is increasing," said a Saudi who works in higher education. "I always say on Twitter that the Wahhabis...have to do self-criticism. Renew and review. This is best way."

Those who publicly criticize Wahhabism today have a larger audience than their predecessors did because of the Internet, which has opened Saudi minds and melted the kingdom's isolation. But they still risk retaliation, depending on how daring or political their writings are.

Liberal novelist Turki Al Hamad, a long-time critic of Wahhabism, was arrested in December 2012 and held for five months for tweets that the government deemed went too far. One of them, translated by Guardian journalist Brian Whitaker, read: "The Prophet came with a humanitarian religion but some changed it into anti-human religion."

Mohammed AbdulKareem, another critic, was jailed briefly in 2011 and one of his three books, Deconstructing Authoritarianism, is banned in the kingdom. Although he remains on the faculty of Al Imam Muhammed bin Saud Islamic University, a bastion of Wahhabi thinking, he no longer is allowed in the classroom.

In an interview, AbdulKareem said that his main thesis is that "we cannot build a society…[where]...security is above justice. No. We need to have justice above security. This is the most important theory that we need to change in our Islamic traditions and preaching."

He sees "a big change" in Saudi young people who "are looking for individual freedom and rights, not for religion," he said. "It's clear to me that because of the Arab Spring, people discovered the ideas of human rights and individual freedom. Why do you expect that people would return to religious trends when...these trends and religious institutions didn't pay attention to human rights and the freedom of the people?"

By contrast, although Al Salem has written scathingly in Saudi newspapers about Wahhabism he suffers no reprisals. This stems in part from the fact that he steers away from politics. Also, as someone trained in religious studies, he argues his case for reform in the same religious language used by religious officials.

In an interview, Al Salem said that his views began changing when he spent seven years in the United States, getting his masters and a doctorate in international finance at Clark University in Worcester.

"In the United States, I started opening up and looking around," he said. "After a time, I found that a lot of Islamic [legal] rulings don't make sense because they are human opinions and not based on the Quran or Sunna."

Sunna refers to the written traditions and customs of the early Islamic community, which includes the sayings of Prophet Muhammad.

He also came to believe that Muslims are harmed when clerics issue rulings on every small detail of life because this keeps them from resolving problems and moral issues on their own. "I think when you are raised completely not to think in a very huge part of your life...it doesn't make sense," he said. "It's very difficult to live all of your life just listening [to clerical rulings] and if you do not allow your mind to think, you cannot be independent, creative and analytical."

He also faults Wahhabi clerics for making too many things religiously forbidden, or haram. While some acts are clearly and always sinful, such as adultery, other acts are not, such as sitting alone with a woman. In the latter case, Al Salem said, Muslims should decide on their own to do those acts or avoid them as temptations to sin. "For example, no one should ask me why I am sitting with a woman," he said. "That's not your business. I evaluate the situation and I found it's okay."

Al Salem, who is a consultant for the Advisory Board for Economic Affairs, which is attached to the king's royal court, also said that he has concluded that the Islamic ban on interest is not based on a correct reading of Islamic scriptures.

"I have a very strong, valid argument on interest," he said. "If they just go to the [religious] scholars and ask them formally, officially, 'If Hamza is wrong, tell us,' the scholars cannot say 'Hamza is wrong.'"

But Al Salem contends that the official religious establishment cannot accept his arguments on interest because it would lose public confidence. "That would make a huge collapse in the minds and hearts of people and they would start waking up," he said.

To understand the fundamentals of Islam's moral message, which are found in the Quran, Sunna and the practices of Prophet Muhammad's companions, Al Salem recalled, "Mohammad Al Wahhab said, 'Use your mind."'

That is why, he added, "I'm Wahhabi one hundred percent."

Part Two: Arab nationalism finds a new audience in Saudi Arabia