The photography for this project was supported by the Pulitzer Center and Catchlight.

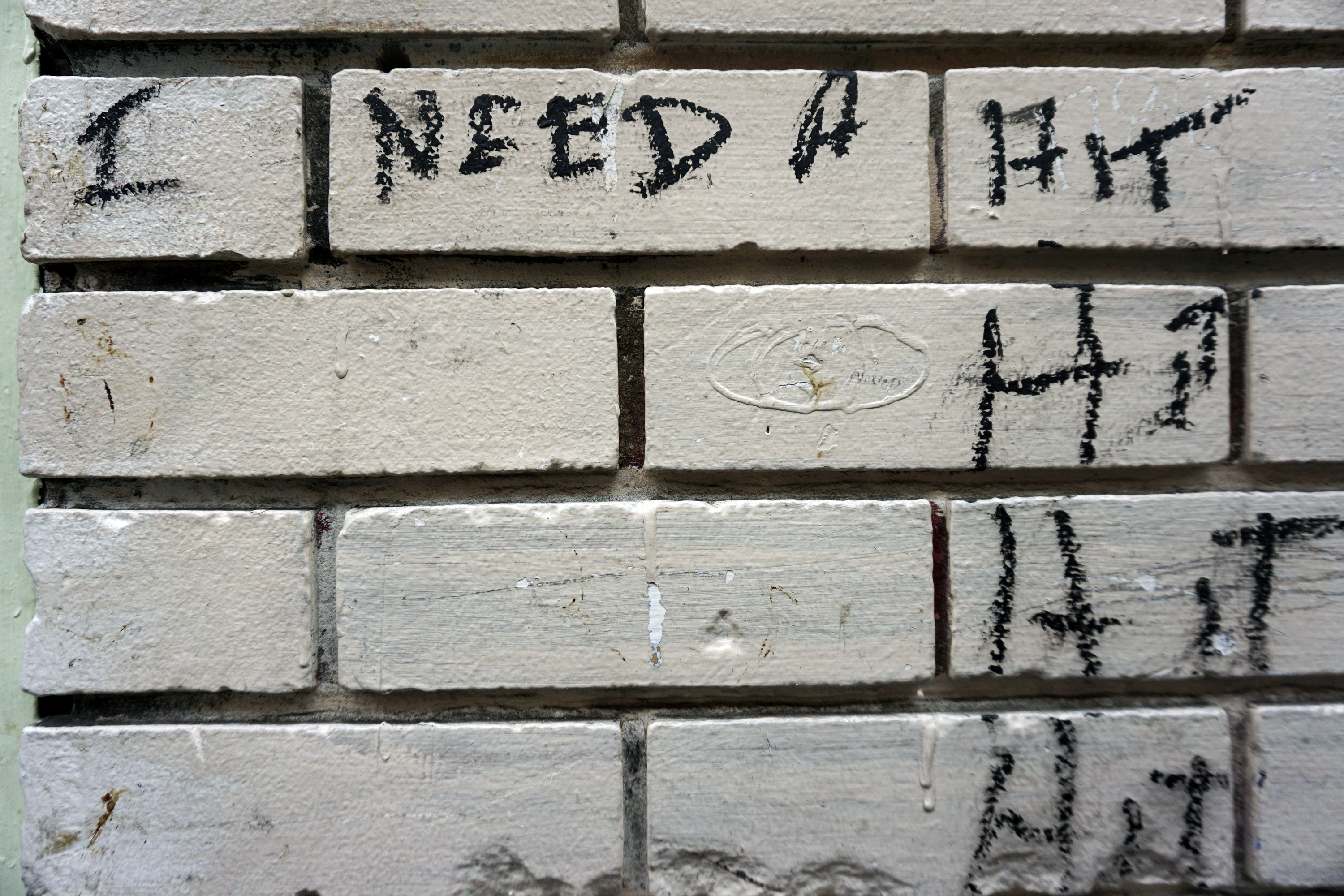

Nowhere is the stark social divide that defines San Francisco in 2018 on display more than in the Tenderloin. The neighborhood has long been synonymous with drugs, prostitution, and homelessness, and it’s now the city’s final frontier for gentrification. It’s not uncommon to spot young, mostly white employees of tech giants stepping over used syringes and human feces on their way to the office.

Eugene Riley knows the Tenderloin as well as anyone. A 25-year-old with the build and personality of an oversized teddy bear, he was raised nearby and still lives here. Now he walks the streets in an orange vest picking up litter, raking leaves, and pulling weeds for the city. He landed an accounting internship in college, but after he pleaded guilty last year to having a concealed pistol in his car, this job is what was available.

I met Riley in the Tenderloin early on a crisp, clear morning in mid-September. He was one of eight students enrolled in a photojournalism workshop for formerly incarcerated people. Our plan was to link up with another student and their instructors, then spend the day shooting pictures of people in his ’hood. We gathered at a coffee shop a few blocks from San Francisco City Hall, across from a federal courthouse.

“This is the trap—people shootin’ up right in front,” Riley said. “And the f—up part is that’s the federal building. The feds is right there. They don’t even care, though.”

He proceeded to give a detailed breakdown of the neighborhood drug markets. Each street had dealers selling different products: We started on the heroin block, wandered through the prescription pill block, and proceeded down Market Street, where he said an entire menu of illicit substances—from cocaine to crystal meth—is available, if you know who to ask.

“You got four corners,” Riley said, gesturing toward men with backpacks hanging out on the street. “If you want some crack, it’s a different block, down closer to the Carl’s Jr.”

The dealers eyed Riley’s camera and my notebook with suspicion, but he was more nervous about the local cops. It was a “jump out day,” he said, which meant officers would be busting low-level dealers and anyone deemed suspicious. He said it happens every Tuesday and Thursday, and it inevitably leads to young, black men like him getting hassled. He’s on probation until 2020, and worried that any contact with police will escalate and lead to an arrest, which would land him back behind bars.

California has overhauled its criminal justice system over the last seven years, reducing penalties for certain lower-level drug and property offenses and prioritizing prison and jail space for higher-level offenders. The recidivism rate fell 2-3 percent amid the changes, according to statewide estimates, but even with significantly more progressive job training programs and services than other cities, nearly a third of inmates released in San Francisco County still end up returning to jail in three years or less.

With states across the country gradually embracing criminal justice reforms, California serves as an example of how former inmates can remain trapped in the system. While successful overall — fewer Californians are being imprisoned, and there’s been no significant increase in crime—ex-prisoners are still struggling to reintegrate into society and permanently break the cycle of arrests and incarceration.

A recent study of inmates from 30 states by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 68 percent were rearrested within three years of release, and 83 percent were picked up again within nine years. Meanwhile, 4.5 million people—roughly one out of every 55 adults in the country—are on probation, parole, or another form of community supervision.

Riley and his workshop classmate Chris Shurn, a 36-year-old from Oakland released on parole in May after serving nine years for robbing a weed dealer, believe the system is setting them up to fail. Both men are eager to move on with their lives. They have jobs and are enrolled in Project Rebound, a program that’s helping them get back into college. But they still live in constant fear that a minor slip-up will get them locked up again.

Shurn, who is short and stocky with flecks of gray creeping into his beard, is still dealing with the consequences of a drug possession charge from three years ago when he was in prison. (He pleaded guilty but says he was wrongly blamed for a small baggie of meth found in a dorm area of his cell block.) In addition to restrictions that come with his parole, he’s been ordered to work for the state, which he expects will involve picking up trash by the freeway.

“Basically, it’s today’s chain gang,” he said. “I have to go to work, I have a family, and I have to go to this other job I don’t even get paid for. It’s exhausting. It’s getting out of one trench and going into another one. If I miss a day or f— up their rules, I could go back to prison.”

Research on the impact of California’s reforms suggests Riley and Shurn are right to wish for a clean break with the system. According to a recent report by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California, the re-arrest rate for offenders who receive “split” sentences with jail and state supervision is nearly 8 percent higher than for those who do “straight” time — usually a longer sentence, but with fewer post-release restrictions.

The report notes that “while it could simply be easier to detect reoffending” when someone is on probation or parole, it also leads to more “non-criminal violations,” which means everything from failed drug tests to missed meetings to merely being on the wrong block in the Tenderloin on the wrong day of the week.

When I called the San Francisco Police Department to ask about the “jump out day” that Riley mentioned, Officer Robert Rueca said there was no such thing. But he did say that the police are “constantly” patrolling the Tenderloin and hopping out of their cars to make arrests.

“That happens on a daily basis as we see a crime being committed, whatever that crime might be, we exit our vehicle as expeditiously as possible,” Rueca said. “Every level of crime is being addressed, whether it be strictly quality-of-life issues to the most serious of offenses, we're dealing with that.”

Walking around with Riley and Shurn, it’s easy to see how a random encounter could escalate into trouble. They are both at ease in the street, chatting up drug users and homeless people just as easily as they do a businesswoman taking an afternoon coffee break, but there’s an edge to some of the interactions.

Down the block from a transit hub, we pass a disheveled man who is slumped over and unresponsive. His friends are yelling and trying to wake him, and one dashes off in search of Narcan, the opioid-overdose antidote. Paramedics show up and deliver the medication, jolting the man back to consciousness.

Their teacher, photographer Brian Frank, advises them to stop taking photos at the request of the man who overdosed, but he appreciates the hustle. “Boom. Right in the face,” he says. “You know how long it takes to get most students to do that? These guys were just doing it from day one.”

As we walk away, Riley points out a group of Latino street dealers who he says were watching us closely throughout the encounter. He doesn’t like the way they’ve been looking at us, but he understands that they’re just protecting their turf.

“This is their store,” he said. “They gotta be on it every single day. It’s not a nice, warm, loving environment. You gotta have that bully mentality. It’s like this bag of weed or coke or heroin or whatever is your food for the day. It’s your shower. It’s your bed. Your livelihood is dependent on making it gone at the end of the day.”

Riley knows what that’s like, from experience. His mom struggled with addiction and kicked him out when he was young. He was in a group home when he finished middle school, then bounced around among six high schools in four states. Despite his nomadic upbringing, he showed promise as a student and a violinist. He recalls with pride the time his school band played Bach for Sen. Dianne Feinstein, but he says his heart was never in it.

“My motivation for playing it was so I could leave school,” he said. “They let us play in like the old folks’ homes, and we used to get free McDonald’s. I did it for that.”

He dropped out of college before he could finish his degree in accounting and ended up back in his old neighborhood, where he was arrested on the gun charge during a traffic stop last year. He claims the gun actually belonged to a passenger in the car, but he told the police it was his in order to keep his friend, who was on parole, from getting a long sentence. Riley had a clean record and says he knew he wouldn’t get much jail time. He ended up serving four days and pleaded a felony down to a misdemeanor.

“It changed how people treat me,” Riley said of his arrest. “They say when you go to jail, you get to find out who your real friends and family are. I was looked down on for being stupid. It was a very unsupportive situation. It was definitely a turning point as far as the type of people I had around me.”

He was homeless for a time, couch-surfing around in the homes of friends, but his job with the city now earns him enough to pay for a small apartment, known as a “single room occupancy,” which means it’s a bedroom with a shared bathroom down the hall. He plans to go back to school, but Shurn is worried about him.

Shurn has more than a decade on Riley, and he’s been in and out of prison his entire adult life. He hopes his young friend doesn’t end up going down the same path, but he sees Riley in the streets and understands what he’s going through.

“I see the struggle and the things he do, it actually brings back a lot of memories,” Shurn said. “When you get older, you look at things differently. You weigh the scales. Is this worth it? Do you got it in you? If you get caught, can you do the amount of time you’re gonna get?”

Shurn had some experience with cameras before the photojournalism workshop. He was featured in “San Quentin Film School,” a 2009 documentary that followed nine inmates at the notorious prison as they took a class on filmmaking and produced their own movie. He’s also profiled in “Life After Life,” a documentary that chronicles the lives of three men after their release from California prisons.

Riley described Shurn as having “charismatic energy,” and it showed when he was chatting up people on the street. On one block, we encountered a rail-thin woman who had blood smeared across her face. It would have been easy to keep walking and avoid eye contact, but Shurn paused to strike up a conversation.

She didn’t give her name to Shurn or want to have her picture taken at first, but soon she warmed up to him and he had her striking poses like a fashion model. “I need that smile again,” he said. “You playing me. You know you got a beautiful smile.”

The woman told Shurn that her drug of choice was meth, and judging from her appearance and behavior, she’d been using. He gave her a pep talk before parting ways.

“Come off these streets,” he said. “You do what you do, but come off these streets. Sober up, save some money and don’t spend it on no man, either. You don’t need no dude to make you a complete woman. You’re the most important person in your life. Some people get it backwards and say it’s their kids or their husband, but you’re no good to them if you ain’t right. Do something for me and get it together.”

The woman was so moved that she leaned in to give Shurn a hug and kiss, which he awkwardly tried to avoid by using his camera as a buffer. As we walked away, Shurn said he felt obligated to say something to her because she had given us “a glimpse of her reality.”

“Photography captures a moment in someone’s life, s— that we take for granted,” he said. “Before I could take pictures, but I wasn’t sure what I should be taking pictures of. I didn’t think people would be interested in the shit I’m used to seeing every day.”

Riley has a similar gift of gab, but his instructors have noticed a difference in the way people on the streets of the Tenderloin interact with him, like he’s still too immersed in their world to get a free pass to document everything he sees.

“Chris is more of an OG now — people see him and say things like, ‘Oh, you’re doing school now? Keep it up,’” Frank said. “With Eugene, people are like, ‘Yo, you’re still out here on the block. You can’t be taking pictures.’”

Riley had no real photography training prior to the workshop, but he was clearly eager to learn the trade. Frank and another professional photographer, Justin Maxon, spent the morning giving him tips and light and framing, which he seemed to soak up.

Frank and Maxon said both students show tremendous promise, but there’s no clear path for them to find full-time jobs in the hypercompetitive field of photojournalism.

They would certainly bring valuable perspective to coverage of criminal justice and homelessness. The situation in the Tenderloin has received national attention recently, with the New York Times visiting the neighborhood and describing “developing-world squalor” on one especially gritty block. It was intended to be a microcosm of the growing chasm between rich and poor in the nation’s tech capital, but some readers criticized the story because it focused on complaints about “street people,” without including the voices of drug users and sellers. Shurn and Riley found and heard dozens of those voices in a matter hours.

Shurn said he’d like to launch his own film production company some day, but in the meantime he’s working the swing shift at a factory, trying to provide for his wife and young daughter, and doing his best to stay out of trouble.

Riley wants to get a bachelor’s degree in Africana Studies from San Francisco State University, but he’s not exactly sure where that will take him. When I asked about his dream job, he said he was just trying to make it another 10 years without getting killed or locked up.

“I never even thought about having a dream job before,” he said. “I guess I always dreamed of working for myself or having my own company. If I make it to 35, we’ll see what happens.”