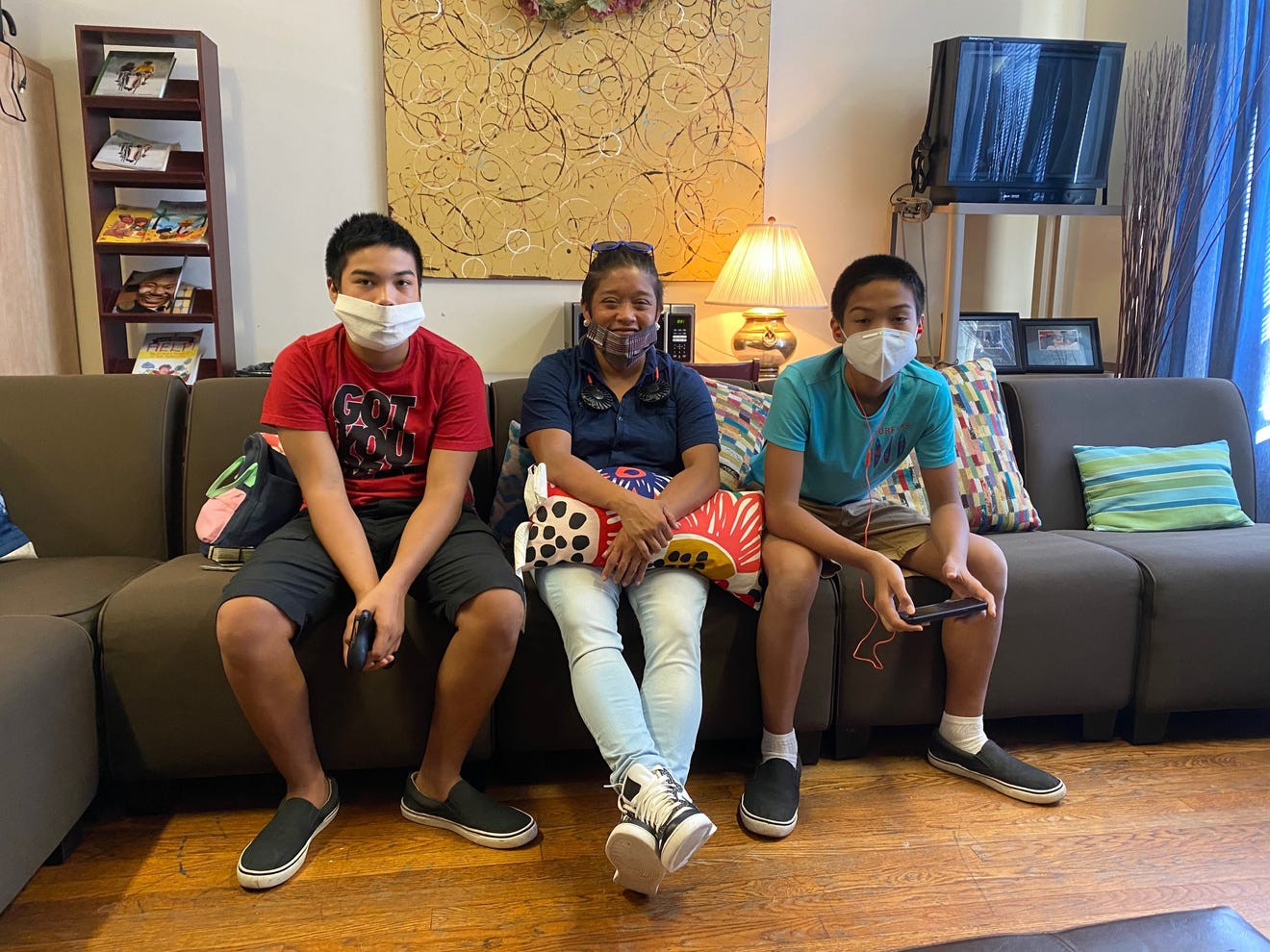

If the state of Florida wants future leaders in STEM — science, technology, engineering and math — the Paco family offers potential. Bradin, age 12, sits at one end of a couch on the second floor of a church and talks excitedly about how researchers found a 26-foot worm off the coast of New Zealand in 2018.

“Scientists are doing some weird stuff,” he says. “They collided human DNA with pig DNA.”

Bradin’s mom, Marica, softly mentions how his teachers suggested he might be gifted and a candidate for advancement. “He’s extremely smart — we’re always bumping heads,” Marica grins. “He knows everything.” Marica herself has a penchant for engineering; she is counting the days until she can start an electrician’s apprenticeship at Mayport. Her other twin son, Cole, sitting to her right on this sweltering Wednesday morning, has a strong interest in math.

Like so many other families in this state, these three have fought to keep their educational plans intact as the coronavirus invaded. It has not been easy.

“I used to do good in my science class when I had to go to actual class,” Bradin says. “Ever since virtual school started, I was failing. I was doing bad in labs.”

Bradin rallied and passed all his classes at Kernan Middle, but now there’s a difficult choice to make about whether to return to face-to-face learning. He and his brother would “rather be in school.” Mom has serious reservations about that.

“I’m glad we had a choice,” she says. “I don’t want my kids returning to school with this COVID-19. It’s too much of a risk factor.”

But Marica and her boys don’t quite have the same dilemma as most Florida families. Their situation is more unique than most.

They are homeless.

Marica, Bradin and Cole are staying at a shelter in town, arranged through Family Promise – a nonprofit, interfaith hospitality network providing temporary assistance for families with children either at risk or experiencing homelessness. They must stay in one bedroom at the shelter for most of their days, as group settings are now unsafe with coronavirus cases spiking all over the state. Marica recently got a job working at a local grocery store – a godsend as she waits for her apprenticeship to start – but the extra work she desperately wants is tempered by her desire to spend time with her boys.

And that dilemma will only deepen if she chooses virtual learning. Keeping the boys away from physical school means the boys will have to spend their days at their aunt’s, in public housing. Marica doesn’t love that option, but the alternative might be quitting her job and sacrificing her apprenticeship.

“My kids had never done virtual before,” Marica says, nodding toward Cole. “He’s more shy, and so it’s harder to help him.”

The in-school experience worries her even more. What if they get sick? How can she even know that the school buses are safe?

“It’s not that I don’t want them to go to school,” she says. “I have to make sure their safety and well-being comes first. That’s my job as a parent.”

The pandemic has brought a perfect storm to homeless families across the region, the state, and the nation. The shuttering of schools has deprived homeless students of not only the routine of daily learning, but also a place of shelter, food, and safety. Students experiencing homelessness could at least count on a meal and air conditioning when school was in session. Now, for many, there is truly no safe place. How do you follow stay-at-home orders when there’s no home to stay in?

“How do you do virtual school,” asks Shannon Nazworth, chair of the state council on homelessness, “when you live in a tent?”

Even the last-resort locations for homeless families bring obstacles or peril. “If you’re sleeping in your car and it’s hot,” asks Family Promise development director Beth Mixson, “would you feel safe rolling down a window?” Shelters can overcrowd. Many parks are closed. (Where do you go to the bathroom if public restrooms are shuttered?) Bus stations offer no social distance guarantees. And those who are couch surfing can’t know how long before they are kicked out. At the church where the Paco family is gathered for this interview, there is a large room with several made beds and closets … but’s it sits empty overnight because it’s no longer safe to fill with families. Hotels around town have stepped up to help, and the First Coast Relief Fund has been reactivated, but those aren’t long-term fixes. The Pacos stayed at an In Town Suites until the money ran out. Marica then called 211 and found Family Promise.

“We didn't have immediate space because we aren't an emergency shelter,” says Tiffany Adams, family support program manager. “I called her and we did an assessment and went from there. We ended up getting an Uber for her to make it downtown from the beaches.”

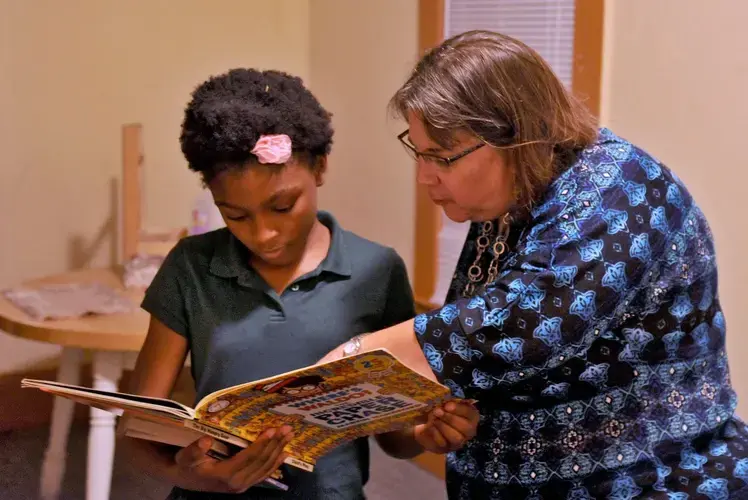

Family Promise did a lot more than that: everything from procuring laptops for the boys from the school district to tracking down Marica’s birth certificate to storing the Paco family belongings while they checked in at the Trinity Rescue Mission. Adams’ colleague, Regina Knighton-Miller, even drove the family to appointments.

“They have literally helped me with everything,” Marica says.

What they can’t help with is a year’s worth of uncertainty every single day: How many hours per week should Marica clock in at the grocery store? How many hours per day should the twins spend at their aunt’s house? How do they get regular exercise in a shelter? (The boys do sit-ups every morning.) How do the boys stay up to pace socially when they never see their friends? How do they continue their religious education? And most pressing of all: should the kids go to school in person?

Student homelessness was a crisis in Florida and around the nation long before COVID-19 arrived. According to the Shimberg Center for Housing Studies at the University of Florida, the poverty rate among school-aged children rose from 16 percent in 2007 to 22 percent in 2015, and the number of students in Northeast Florida identified as homeless increased more than 50 percent in the past decade. And that itself may be an undercount; there is a discrepancy in how student homelessness is tabulated.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development uses a “point-in-time” method that counts homeless on the streets or in shelters on a specific night of the year. This does not include students who live in hotels or couch-surf. So while HUD reported a decline in homelessness among families from 2017 to 2018, the Department of Education reported 1.5 million homeless children and teens during the 2017-18 school year – up from the prior school year.

One thing seems beyond doubt: for a sizeable number of families across America, the Great Recession of the prior decade never ended.

And it got worse in some pockets of Florida. Hurricanes Maria, Irma and Michael displaced many families from the Keys to the Panhandle, and problems persisted long after the cable news cameras were packed away. Now throw in an opioid crisis that spiraled out of control over the past several years, and wages that didn’t keep pace with the price of housing. In the five years beginning with the 2014-15 school year, student homelessness rose from 2,166 to 3,770 in Duval County, and from 73,417 to 91,675 statewide. That was before the pandemic.

“A lot of parents are in jobs that are temporary,” says Tricia Pough, who has worked to serve the student homeless population for Duval County Public Schools for 20 years. “The stock market may be going up but they still can’t find those [stable] jobs. And the rent is going up.”

The effects on academics aren’t difficult to imagine. Students experiencing homelessness in Florida averaged nearly twice as many absences as students with full housing and full lunch. And every teacher and parent knows absences lead to academic difficulty. The Shimberg Center reports homeless students pass their classes in ELA, Math and Science roughly half as often as fully housed and full-lunch students. The Pacos know the struggle all too well; Marica would wake up in the middle of the night in the shelter to find Bradin sitting in the glow of the laptop screen, trying to stay on top of everything.

“A majority of our students love school,” says Pough. “And they’re doing great. But this adds another obstacle to what they’re already going through.”

There’s a blend of chaos and paralysis during this pandemic that makes concentration difficult for everyone, but that’s lessened for those of us who can close a door on the rest of the world. The Paco family has four individual beds, which they’ve pushed into one large bed to give themselves more room to walk around during the day. It’s not exactly conducive to studying or reading.

“I can’t stand being in the shelter,” Marica says. “It’s extremely hard.”

Marica’s been through worse. She arrived on the U.S. mainland with her parents from Guam in the early 1990s. They settled in Georgia, and she married there. But she says that relationship turned abusive and she left in what she still calls her “Independence Day.” She developed a heart condition and moved south to Jacksonville to be closer to her older daughter and her sister – who has ailments of her own.

“Everything we’ve had, we’ve lost in a year and a half,” she says. “We really don’t have much stuff – just the clothes.”

It’s been tough on the kids, too. A few schoolmates figured out that the boys were homeless when they got onto the bus near the hotel where they were staying, and one mockingly offered a dollar. “Bradin almost punched him,” Marica recalls.

There is good news: Marica’s new job at the grocery store, along with her electrician apprenticeship at Mayport, offer a glimmer of a path to stability. The more she works, the closer she gets to a place of their own. But she says if it wasn’t for the ability to send her boys to her sister’s for the school day, she would quit her job. She just doesn’t want Bradin and Cole at further risk – even if it means more months in the shelter. She says she is not sending them into the school this semester, no matter what.

The boys may want to go back to school in person, but they do understand. To be homeless is to have almost no control over anything, and to be homeless during this pandemic is to be even more adrift. Still, the boys don’t act up or act out. During the interview at Family Promise, Bradin continually pulls up his mask to cover his nose, even though he’s more than six feet from anyone. Cole fights to stay alert, even at 10 a.m. Eventually he relents, closing his eyes and laying his head back onto the couch.

“She has two boys that displayed respect during all this,” Knighton-Miller says, “and it is rare when teenagers are humble to what's going on around them.”

There is hope. The boys love their teachers and their teachers love them. Bradin and Cole are not lost in the eyes of Kernan Middle School. The district is invested in making all students feel as normal as possible, if possible. “We want them to feel just because they’re in that situation doesn’t mean they’re treated differently,” says Pough.

Maybe in 2021 there will be two comfortable places for the boys – their school and a new home.

“When we have our house,” Marica says, “I’m just going to stare at the walls for a whole week.”

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.