The ancient Oxus River, today called the Amu Darya, is one of the longest rivers in central Asia, traversing the region as it flows more than 1,500 miles from the Pamir Mountains in the east to its terminus in the Aral Sea. The river forms part of the particularly volatile border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, which is considered to be the main drug route from Afghanistan to the West. Crossing one of the few checkpoints between the two countries alone with a Leica camera and notebook (her “only weapons”), photojournalist Monika Bulaj once startled an Afghan soldier enough to make him forget to stamp her passport. “But,” she says, “he gave me a cup of tea. And I understood that his surprise was my protection.”

In Afghanistan, Bulaj travels by foot, horse, yak, and by hitching rides on trucks when she can. But it was “walking through the forests of my grandmother’s tales” in her homeland of Poland that first sent her on the road. There, she found “a soul of places.” That was nearly three decades ago, and she hasn’t stopped yet, trekking from Eastern Europe to central Asia and beyond, through the Caucasus and the Middle East to Africa, and even the Caribbean.

Her effort to “give a voice to the silent people” earned her Italy’s National NonViolence Award in 2014—making her the first woman recipient—for “shedding light on humanity living in the most hidden yet most evident boundaries on Earth.” This includes the Kalasha, polytheists who offer animal sacrifices in seasonal celebrations, secluded along the Afghanistan–Pakistan border.

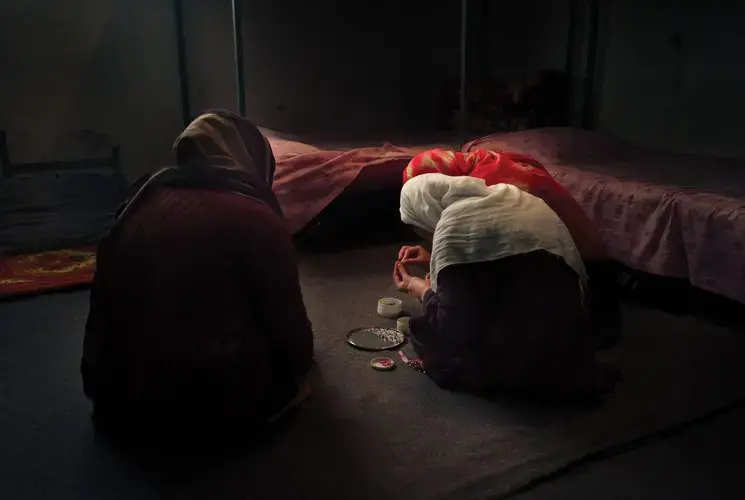

Though they are the third largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, Hazara are also historically among the most discriminated against—in particular, the majority Shiite Hazara. The Hazara were sold into slavery as recently as the nineteenth century. They were subject to religious and ethnic cleansing into the twenty-first century and remain susceptible to attacks by the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), suffering abductions, extortions, violent deaths, and other abuses.

Bulaj has also photographed the effects of forced migration in western China and elsewhere. In a 2003 attempt to protect the headwaters of Asia’s three major rivers—the Yellow River, the Yangtze, and the Mekong—the Chinese government launched a controversial initiative to relocate Tibetan nomads to urban housing in newly constructed villages. The results have been predictably frustrating: There’s little use for the pastoralists’ grazing traditions in the new settlements and government services, including education, are offered in Mandarin rather than Tibetan. In the meantime, this large-scale social-engineering experiment has cost the government upward of $3 billion and resulted in a widening income gap among the urban and newly rural Chinese. Set against the backstory of this bureaucracy are Bulaj’s images of a people in transition, struggling to retain their traditions and sense of self while also trying to assimilate in their new home.

The Old Believers of Romania, who make up less than one half of one percent of the population, have also faced imposed relocation and violations of their linguistic rights. As Christians, the Old Believers (sometimes called Old Ritualists) maintain the liturgical and ritual practices of the Eastern Orthodox Church before its reformation of the mid-seventeenth century. Yet they persist in practicing their religion—the core of their identity—despite centuries of persecution.

In Khushpur, called the “Vatican of Pakistan,” the All-Pakistan Don Bosco Football Tournament, organized in response to 9/11, now draws more than thirty teams from across the country. The tournament is interreligious: Muslims and Christians play together as a way of promoting peace and interfaith dialogue. Christians and Muslims serve as referees and linesmen. For seven days, the teams play soccer, share meals, sing, dance, and pray. It is these “shared sacred places along the borderlands of monotheism” that Bulaj seeks to highlight through her work, showing that the divisions in humanity don’t always divide.

– Allison Wright