In 2000, Naomi Oreskes, a geologist by training, was working at the Scripps Institute for Oceanography in San Diego, an organization with a long history of climate change research.

"All the scientists around me spoke about climate change as if it were a settled matter. Proven scientifically. Manmade," recalls Oreskes, a renowned Harvard professor specializing in the history of science. "Yet I noticed that in the media, the issue was reported as if there were a big debate over whether it was even real. That contrast led me to the work I published in 2004."

Oreskes, whom The New York Times has called "one of the biggest names in climate science," did what any interested party could have done then, but didn't. She counted the scientific papers on climate change — 928 at the time — and determined that not one disagreed: all found that climate change was real, underway and manmade. She exploded the myth that any debate existed. The media took notice; and she, of course, came under attack from climate science deniers.

Bad idea. Oreskes is nothing if not tough, thick-skinned and fearless in proclaiming the truth as she sees it, based largely on her abiding confidence in the scientific method. In 2010, she co-authored "Merchants of Doubt," with Erik M. Conway, which exposed how the same people who lied about the dangers of smoking, did the same for acid rain, and now for climate change, placing corporate profits above public health. And winning the war of public opinion.

In an exclusive interview with Mongabay, Oreskes offers her candor and scientific insights into likely the most daunting challenge facing humankind — coping with current political denial and inaction, against the dire scientific reality of a rapidly warming planet.

Mongabay: The Paris Agreement signed by 195 countries last December has been hailed by many as an historic breakthrough. But scientists are loathe to give it much credence, and environmentalists like Bill McKibben have been dismissive. Where do you stand?

Oreskes: It's tricky. I certainly understand scientists who look at it and say, "It's just intentions, it's just talk, there is no penalty for noncompliance. How can we take this seriously?" A lot of scientists think in forms of definiteness, so this is tough for them. They don't like ambiguity.

So it's not surprising to me that the science community has had trouble seeing this as a success. But I think that's wrong. This is a political document, it's a political agreement. And essentially, it says for the first time—and this is really important—that all the nations in the world are saying climate change is real. It's serious and it's a threat to the prosperity of mankind. That alone is huge.

Mongabay: Curiously, the corporate world seems more accepting. What do you make of that?

Oreskes: One of the things businesses have been waiting for, for a long time is a clear signal from political leaders that they are going to take climate change seriously. If you are a corporation trying to decide whether to invest in energy efficiency or emissions controls—or maybe you're a Shell or BP and you're really trying to decide if the time has come to change your business model—it's hugely important to believe that governments are committed to this. Future tax structures are going to favor non-carbon-based energy.

Mongabay: Oil dropped $7 a barrel the day after the Paris Agreement was signed.

Oreskes: Bingo! So I think that's something the scientific community doesn't fully understand. The market responded, right? The Paris Agreement is a statement of intent, and those are important, too. Before you can act, you have to decide to act. This is a decision to act.

Does that mean the world will act, or act in time? Of course not. So that's where the work has to be done now. But I think it's a big mistake for scientists to be dismissive of this agreement.

Mongabay: In 21 years, this is the first time forests have been mentioned in a United Nations climate document. It's always only been about reducing emissions. REDD+ is mentioned specifically.

Oreskes: Yes, but forests have been on the radar screen, and part of the scientific conversation, for a long time. When I give talks, I ask: "What country has done more to reduce emissions than any other country?" People almost always say Switzerland, or Sweden, or some other nice Nordic place. But the correct answer is Brazil because of the efforts they've made to control deforestation.

Forests have been on the [UN] radar, but having it become formalized and official, that's important. It makes it clear that countries like Brazil, Indonesia and the United States—if we take up the goal of reforestation—that these countries have a very important role to play in this future.

Mongabay: Do you find the voluntary nature of the Paris Agreement, the lack of enforcement mechanisms, concerning?

Oreskes: I do, but not in the way you might think. It doesn't concern me that it's voluntary in principle. At the end of the day, any agreement isn't worth the paper it's written on if it's not enforced by the people who committed to it. The UN has no authority to impose a carbon tax or emissions trading system. Only national governments or the European Union have that kind of authority. At some level, it has to be implemented on the level of the nation states that are part of the agreement.

But the reason [the voluntary aspect] upsets me is because of the role of the United States. The reality is that the U.S. has been the single biggest obstacle to a huge amount of potential [for dealing] with climate change. It goes back to Kyoto, where we insisted on emissions trading as the appropriate mechanism, convinced Europeans to go along with that, then we scuttled the accord at home. And again, we're playing an obstructive role, saying we will only agree to something that's voluntary. So even though we [in the U.S.] like to act like we're a great international leader on this issue, not only have we not led, we've been an obstacle. That's sad and depressing as an American who loves my country.

Mongabay: And then there's the Supreme Court's unprecedented recent decision to stay the implementation of President Obama's EPA mandates to control emissions from coal.

Oreskes: That 5-4 decision [a week before conservative Justice Scalia died] was absolutely a political decision at so many levels — something the conservative wing insists they are above.

The Circuit Court did not agree with this. The Supreme Court itself had told the EPA that under the Clean Air Act, it was required to carry out these mandates. They had sent it back to EPA, which was the correct reading of the law. And now they are saying we ought to wait until all the legal challenges are finished. That could take forever. It's just so hypocritical that it makes my teeth hurt.

Mongabay: New York and California U.S. attorneys are looking into suing fossil fuel companies for lying to shareholders about what they are said to have known all along about the connection between burning fossil fuels and their contributions to global warming. Will such a suit get any traction?

Oreskes: Based on what evidence we have so far—we haven't had a trial yet—it certainly appears that there has been a misrepresentation to shareholders regarding climate risk.

SEC regulations require corporations to make sure shareholders are aware of issues that can potentially represent a financial risk to the value of the company and its shares. So if the company knew that climate change meant there could be stranded assets, then they have had an obligation to share that information with shareholders. Now they might argue that until recently there was no credible threat of stranded assets. But that becomes a judgment call.

Mongabay: Explain stranded assets.

Oreskes: Assets you can't sell. This applies to oil, gas and coal concessions that they are sitting on, or reserves of oil, coal and gas that they may not be able to sell, or [for which] the value may decrease dramatically. If Exxon has reason to expect that could happen—they had an obligation to tell their shareholders.

Mongabay: Given the Paris Agreement, given the potential lawsuits, given the growing global consensus around the reality of climate change, and the urgency for action, do you believe we're at the tipping point for fossil fuels?

Oreskes: It's the nature of tipping points that you don't know if it happened until you look back on it. The amount of information out there now is so overwhelming, and changes are already happening, it should be the tipping point.

This is why I have such a low opinion of Exxon Mobil. I think they have placed themselves in what I call the "tobacco position." Even now with mountains of scientific evidence and damage being done, they are still dug in.

But they have alternatives. They can stop looking for new oil and gas reserves, and shift to renewables or carbon capture and storage. It's not like there is nothing else they can do to make money. But it would require a massive shift on their part, and [there would be a lot] to explain to their shareholders [as to] why it's time now to make this change. They can do it. But there is no sign that they will. And that's the tragedy here. They could do the right thing.

Mongabay: This leads me to a tricky question. Barack Obama is the first U.S. president to do much of anything about climate change. Yet he continues to approve the further exploration of fossil fuel reserves through fracking and offshore drilling. How do you make sense of his environmental legacy?

Oreskes: I don't make sense of it. John Holdren, Obama's scientific adviser, has told me the President understands these issues. That he gets it. But it's very difficult to square that circle. Because if you really understand this issue, you can't understand the [president's] decision to open up areas for new [oil] exploration.

Obama claims to have an energy and climate policy. But he doesn't. He has an energy policy. When he announced a long time ago that he was going to have an "all of the above" strategy, that was an energy policy, not an energy and climate policy. If the United States is just worried about energy then we can frack for gas and oil, we can burn coal. We have huge energy reserves in our country.

If we are worried about energy and climate, it's a very different picture.

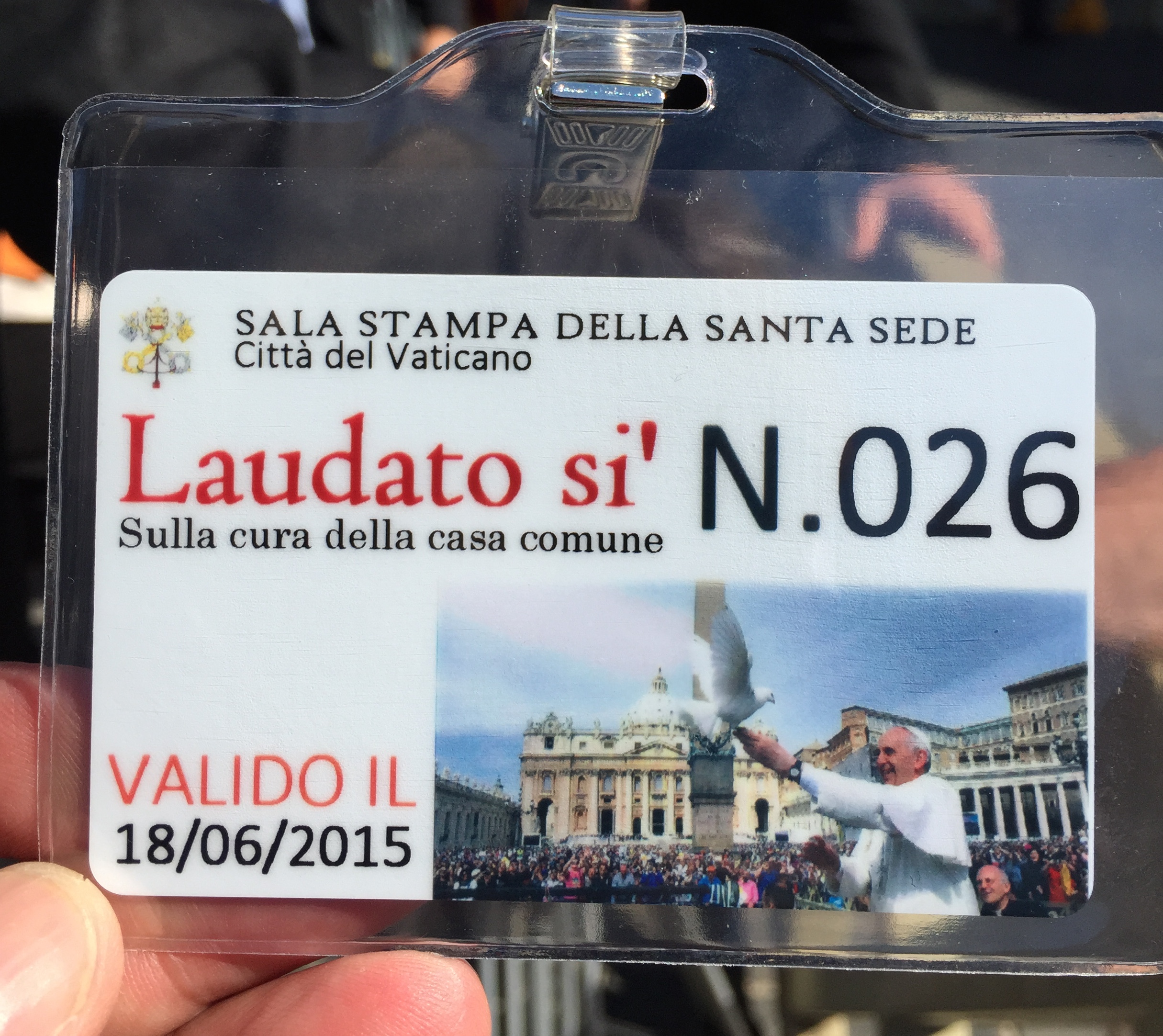

Mongabay: You wrote the introduction to the U.S. release of Pope Francis' historic papal encyclical Laudato Si, On Care for Our Common Home. What resonates most with you about that document?

Oreskes: Linking climate change to poverty has been incredibly powerful. I think Pope Francis hopes it will help empower other political leaders who want to speak out on this issue and feel like they are not alone. It hasn't had a dramatic affect yet. But everything always takes longer than I think it should.

One of the ironies of this document is that the polls show so far that the majority of [U.S.] Catholics did not recall their own priest discussing Laudato Si in church on Sunday. But it's getting out there. I don't think we know yet the full extent of [what] this encyclical will be. But I think it's significant.

Mongabay: I have a simple question as we wrap up: How much hope do you have?

Oreskes: That's a trick question!

Mongabay: I know. So much damage is already baked into the climate system.

Oreskes: That is true. You know the joke: an optimist is the person who thinks this is the best of all possible worlds, and the pessimist is someone who fears that it is!

I am intrinsically an optimistic and energetic person. But it's difficult to stay optimistic in the present moment, especially in the face of continued denial of people who should know better. I think that's disgraceful and shameful. It's also upsetting and depressing when you look at the impact of climate change already underway.

It's more like I feel sad. There is a kind of sadness associated with the fact that at some level, we've blown it. We had the opportunity 20 years ago to act on this issue before climate change was locked in. We knew what to do 20 years ago.

It's a cliché to say that knowledge is power. It's not true actually. Knowledge is knowledge. In our society, knowledge resides in one place, and for the most part, power resides somewhere else. And that disconnect is really the crux of the challenge we face right now.

Mongabay: You want to end on that note?

Oreskes: No! I don't want to end with that. What I want to say is that at the end of the day, pessimism is not acceptable. It becomes an excuse for giving up. And I reject it.

We cannot give up the fight because it's not too late to avoid the worst damage, and there is still a lot to fight for and save and protect, including the opportunities for our children to have lives as good and prosperous and beautiful as our own. I don't know the remedy. And in me, this is cause for anxiety, if not downright pessimism.

Mongabay: That's a much better way to end.

Oreskes: Ok, good. Laughs