In North and South Carolina, sea-level rise is most noticeable in counties along the coast, where beaches shrink, dunes disappear and homes crumble, but the effects of climate change reach well inland. “Beyond the Beach” is a seven-part series examining the health toll that climate change is already taking on the people who live and work in the Carolinas.

The project is a partnership of The News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina, The State in Columbia, South Carolina, Columbia Journalism School and the Center for Public Integrity. Funding support for “Beyond the Beach” came from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School, also contributed to the project. Funding for CJI comes from the school’s Investigative Reporting Resource and the Energy Foundation.

Pamlico County, wedged between its namesake sound and the mouth of the Neuse River, is surrounded by water on three sides and is a target for hurricanes that sweep up the North Carolina coast.

In 2011, Hurricane Irene made landfall near Cape Lookout and dropped more than 17 inches of rain over part of Pamlico County. Flood waters inundated Pamlico County homes, including those in Vantisha Williams’ old neighborhood.

When the floodwaters receded, mold growth followed. And that, Williams believes, triggered her daughter Nazri’s asthma. Nazri was then 3 years old.

“I remember making sure her nebulizer machine wasn’t wet,” Williams said.

Breathing problems and asthma medications are constants in the life of her family, which now includes twin 4-year-old sons Jonathan and Jeremiah. After storms, everyone starts coughing, she said.

“The humidity, the debris everywhere, the wetness, it could be making the asthma worse,” Williams said from her Bayboro home. Health problems also are compounded by storm-related power outages that prevent the children from getting their breathing treatments.

In Eastern North Carolina, more people make trips to hospital emergency departments for asthma treatments than in any other part of the state, say researchers at East Carolina University. The researchers have been focusing on the connection between climate change and asthma, a chronic inflammatory disease, in the eastern counties.

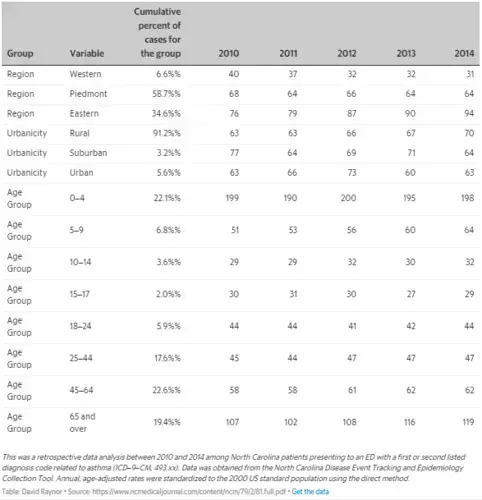

A study of asthma-related emergency room visits from 2010-2014 found that, as a group, eastern counties had the highest rates of hospital emergency department visits, compared to Piedmont and western counties. More than 90 percent of emergency department visits were from rural counties, according to the research published in the North Carolina Medical Journal in 2018.

Asthma-related emergency department visits trended up in eastern counties over the five years, while they were largely flat in the Piedmont and trended down in the west.

Greg Kearney, an environmental health professor and one of the paper’s authors, said in an interview that mold growth in the aftermath of flooding is part of the problem.

“There’s no doubt that is a huge asthma trigger,” he said.

Climate Change Affects Mold, Asthma Patients

Housing, air quality and other environmental factors contribute to ill health. Kearney said the connection between climate change, severe hurricanes and asthma in eastern North Carolina is being discussed a lot more since Hurricane Matthew in 2016, Hurricane Florence in 2018, and Hurricane Dorian in 2019 drenched North Carolina.

“Indirectly, climate change is impacting asthma through flooded homes and creating housing problems that people can’t afford to fix,” he said.

“When things start to heat up, that’s when the mold really takes off. People who have allergies or asthma really suffer the most.”

The North Carolina Climate Science report produced last year said it is very likely that hurricanes hitting the state will bring heavier rains. All that rain, in turn, will increase the likelihood of freshwater flooding. The North Carolina climate scientists report said continued sea level rise is virtually certain. Higher sea levels and extreme hurricane rains will increase storm surge flooding.

Preparing for and picking up after hurricanes is a part of life in Pamlico. Pamlico High School sports teams are called the Hurricanes and business signs point to Hurricane Barber and Hurricane Boatyard. The Neuse River and creeks that attract boaters and recreational fishers to Pamlico are the waters that threaten homes and health in storms.

“We’re surrounded by creeks,” Williams said. “All of that starts to rise when the surf comes in. That’s basically what floods us.”

Pamlico has lots of older houses, Williams said, and even when water doesn’t rise high enough to get into living spaces, it seeps in underneath. “It just kind of sits,” she said.

Other Factors That Trigger Asthma

But the region is also rife with other environmental factors that trigger asthma.

The North Carolina Climate Science Report says absolute humidity will increase as the climate changes. Humid air can be an asthma trigger.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Georgia and North Carolina universities looked at connections between air quality and asthma deaths among North Carolina children. Between January 2001 and the end of 2016, 81 children from age 5 to 19 years old had asthma as their primary cause of death, researchers found. They reported a connection between high humidity and those asthma fatalities.

They also looked at percent relative humidity across three ranges. At the highest range, 81.2% to 95.9%, they found that each percentage increase in relative humidity was associated with a 16% increase in the odds of fatal asthma.

Fifty-four percent of the children who died were boys, and 82% of the children who died were Black, the Georgia and North Carolina researchers found.

Age-Adjusted, Asthma-Related Emergency Department (ED) Visits by Region, Urbanicity, and Age Group (per 10,000 Persons per Year)

Kearney’s research says that eastern counties with the highest asthma rates were also the poorest counties with a high proportion of Black residents.

The shock from the historically wet and destructive hurricanes of a few years ago may be fading for inland residents, but many people in coastal counties continue to live with the after-effects.

Randolph Keaton, executive director of Men and Women United for Youth and Families, said his organization is still working with families to get hurricane-damaged homes repaired. The non-profit helps people in Bladen and Columbus counties with Hurricane Florence disaster relief.

The COVID-19 pandemic has slowed home repairs.

“We still have roofs that need work,” he said.

“With COVID and these houses still damp, then with weather like this that’s so hot and humid, the crawl spaces in these houses are terrible,” Keaton said in an interview with the N&O this summer. “It really creates for poor people a double whammy.”

Keith Graham is a senior case manager at Men and Women United working with families in Bladen and Columbus on home repairs. A dozen people still have mold problems, some of them severe. A problem with getting work done is that the mold remediation costs more than half the home value.

People with respiratory problems are living in homes with visible mold, Graham said.

“It’s in the attic, there’s mold in the walls, under the house,” he said.

In another home, a child is living in a home with a recurring mold problem, Graham said.

“They’ve done several things to treat it. It’s still there.”

Limited housing options and pandemic restrictions this spring and summer meant to encourage people to stay at home meant some families were trapped in houses that were making them sick, he said.

“Before, they were busy. Now they’re stuck at home and it’s even more depressing,” Graham said.

Mold: ‘The Smell Was Unbearable’

Hurricanes Matthew and Florence drove Shalonda Regan and her family from their home in South Lumberton after Hurricane Matthew in 2016 brought historic flooding to the Lumber River. Water inundated neighborhoods that had not been flooded in previous hurricanes, including Regan’s.

Regan, who works for a non-profit after-school program, said three feet of contaminated water flooded the split-level home.

“It was like a really bad, brownish-red color,” she said. “The sewage had come in. The smell was unbearable. Those were conditions I couldn’t be in.”

FEMA had deemed the house livable because the upper level of the split-level house wasn’t flooded, Regan said. She couldn’t live there because the mildew triggered her asthma.

She lived in her mother’s boss’s unoccupied apartment for a month, she said, before she was able to move back home.

Two years later, Hurricane Florence dropped more than 22 inches of rain on parts of Lumberton, flooded the river and damaged hundreds of buildings in Robeson County.

Hurricane Florence didn’t do as much damage to the family home, Regan said. About a foot of water came in, and she didn’t have to stay away from the house for as long.

Regan said her asthma has improved, though she still carries an inhaler.

Months after Florence hit, Vantisha Williams’ boisterous sons were still fighting back-to-back asthma flare ups. Her daughter complained of constant headaches.

You can tell by the smell when major flooding has hit Pamlico, Williams said.

“Even though the storm passes, that water is still around,” she said. “It smells different around here. It’s just a stench. Then you have the sewer water come up. It’s just a lot. Some people lived in their houses after they were wet. They didn’t want to leave their houses and they didn’t have any place to go.”

This story is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative. For more information, go to pulitzercenter.org/connected-coastlines.