With unfailing precision the desert measures out time in forevermore repeating segments.

It is the age-old pace of almond orchards that are pearled with flowers now and in two weeks will be glaucous with miniscule teardrop nuts. Of goats kidding in the greening fields. Of babies born and dying of malnutrition and disease. Of the three-hour predawn trek to market as stars wink out one by one in the paling sky and the earth rings under the donkey's hooves. Of lavish weddings and meager harvests and raids by foreign invaders.

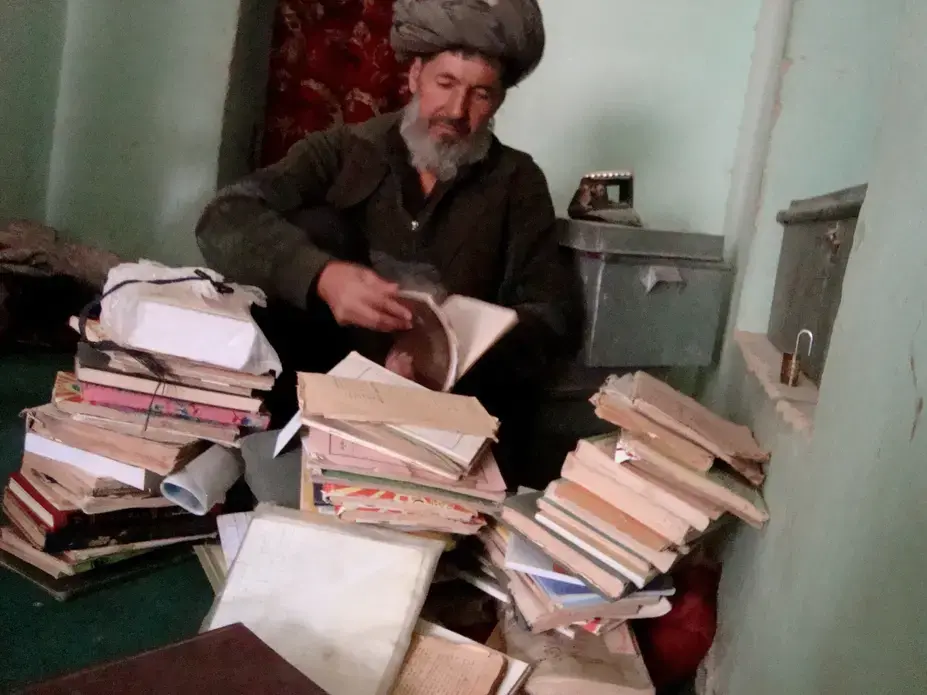

As a village timekeeper, Hussein Ali is a bit of a bumbler. The milestones he has recorded in his scrapbooks over 40 or so years are sporadic and of varied consequence. The entries reflect his own notion of what merits documentation in his farming village of ten-score crooked clay streets twisting past walled orchards and irrigation ditches foamy with snowmelt. There's the 2009 reelection of President Hamid Karzai -- and the wedding of the son of Ghiaz Bai and the daughter of Mullah Faizullah on the 22 of mesan, Persian year 1389.

There's the record of the storm five years ago, during which two of Karaghuzhlah's 10,000 people died of terror in the desert. An entry that describes last month's frightening nighttime raid by American troops in helicopters, who took away one suspected insurgent and created many new enemies, villagers who gathered by water pumps and mosques to swear revenge the next morning. A brief bio of Ahmad Zahir, the Afghan pop star who was killed in a car accident in 1979.

"Everything I find of importance for posterity I keep here," Hussein Ali says. He opens a scrapbook randomly to the page where some 20 years ago he summarized, in four or five handwritten paragraphs, the history of Italy.

The villagers call him, deferentially, the Historian.

Outside the smoky guestroom of the vast family compound the Historian shares with his 70 relatives, almond petals flitter down to the dust. Inside, unshelled almonds from last year's harvest glow dully in pewter saucers. The time for planting and the time for reaping, the past and the future, converge.

Afghanistan can feel like a temporal Grand Canyon, a land in which you can journey through millennia in a matter of hours. In the mornings I buy ice-cold pomegranate juice at city shops and head to villages where the fastest mode of transportation are the donkeys on which men travel to market towns on bazaar days and barter tumbleweed for rice. It is also a land that has been at war nearly perpetually since the beginning of recorded history, a fact that fuels doubt that Afghanistan, which has withstood scores of invasions and fratricides with time-earned tenacity, can ever find peace.

Artifacts of invasions past and present tower over the northern Afghan desert. Within an hour's drive from Karaghuzhlah rise the eroded walls of an enormous Kushan castle. Buddhist stupas. The ruins of Balkh, wrecked first by Alexander the Great, then by Genghis Khan -- whose massacre of the city residents heaped the fields with so many dead that, in the words of the historian Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini, "for a long time the wild beasts feasted on their flesh, and lions consorted without contention with wolves, and vultures ate without quarrelling from the same table with eagles." A 12th-century Arab minaret, which, some records indicate, doubled as a watchtower. The empty shell of Takht-e-Pul, an 1850s fort whose walls, bisected by the road that connects the cities of Balkh and Mazar-e-Sharif, served as ideal ambush cover first for the anti-Soviet mujaheddin, then, in turns, the Taliban and anti-Taliban guerrillas. The most recent additions are the 15-foot concrete blast walls of a NATO military base near the Mazar-e-Sharif airport, now housing thousands of American troops.

I pilgrimed to Karaghuzhlah to ask the Historian how he thinks the war here will end -- or go on forever.

"Everything takes time," he says. "But we need a government that is more concerned with the needs of its people."

In the decade since the U.S.-led invasion, billions of dollars of international aid have poured into Afghanistan. Mansions and exquisitely manicured gardens have gone up in Kabul. Still, no paved roads lead to Karaghuzhlah, and no power lines connect it to Afghanistan's spotty electric grid. Tiny village mercantiles sell matches from Pakistan, soap from India, and long-life coffee cakes from Iran. Hussein Ali's brothers, almond and wheat farmers, complain that the government is allowing imports to take over domestic markets. They bring their almonds -- they grow seven different varietals -- to market by zaranj moto-rickshaw; the 20-mile trip to the nearest town takes more than an hour.

"In the past," Hussein Ali offers a historical perspective, "we went by donkey and it took four hours."

The Historian has committed to memory hundreds of history books in Dari, the language mainly spoken here. At one point his library was "too big and heavy for one donkey to carry," but a group of Soviet soldiers piled it in the dust and burned it at some point in the 1970s. (Though not, he points out, before taking with them his gilded 17th-century copy of the Koran, a gift from his father.) We chat a bit about his pet subject, Afghanistan's incessantly warring rulers.

His favorites are Ahmed Shah Durrani, known as the Father of the Nation, for expanding Afghanistan's borders from the Oxus to the Arabian Sea in the mid-1700s; his son, Timur Shah, who is remembered fondly for transferring the capital to Kabul (and less fondly for having violated the Pashtun code of honor when he tortured to death two conspirators even though they had sworn the oath of loyalty to him on the Koran); and Amanullah, who proclaimed Afghanistan's independence from the British empire in 1919. Strong men. Often ruthless men.

I point out that none of these rulers had brought peace to Afghanistan. Hussein Ali pauses to think.

"The only peaceful ruler we had was Zahir Shah," Afghanistan's last king, the Historian says at last. "We had no war for 40 years. But he did nothing for his people. Instead, he preferred to go hunting and live in luxury."

Zahir Shah's bent for luxury appears to have been an inherited trait. In the evening, absurdly yet fittingly, I find myself in the company of the last king's young cousin. The king's cousin is a real estate mogul; he has been drinking since morning. His wife in Kabul, he explains, does not allow him to drink -- for reasons of health or faith I never learn -- so he does his bingeing on the road. I try to have a conversation with him but he is too inebriated. Also, there is live music in the room: a keyboard player who sings into a microphone outfitted with an '80s disco-style delay, and a boy of about 12 who plays tabla fabulously.

After a few attempts to outshout the music (and sneaking one more scoop of the king's cousin's crème brûlée-flavored ice cream) I retire to the bedroom and fall asleep to drunken revelry downstairs and the sinister rumble of B-52s above.

I awake the next morning to blood-orange dawn and calls to morning prayer, amplified by megaphones at mosques all over the city. As they have done for centuries, dozens of muezzins begin intoning their intricate cadences simultaneously -- and, it seems as the sun crowns above the Khorasan plains, at precisely the right time.