Margaret Nakyanzi, 54, lives in a small mud-wattle house roofed with a mix of old and new corrugated iron sheets in Gomba, about 80 miles south of Uganda’s capital city, Kampala.

Nakyanzi had relied on her son, Robert Ssenyonga, 20, for survival. However, he died in July 2020, a week after he was allegedly hit with a gun on the forehead by a Local Defense Unit (LDU) soldier who was implementing government coronavirus lockdown Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs).

When he left home in December 2019 for a manual job in Buikwe district, where the fatal incident happened, 46 miles east of Kampala, Ssenyonga promised his mother that he would work hard and support her.

The army denies that Ssenyonga was beaten by the soldier. However, interviews with five people, including an 18-year-old friend he was transporting on a motorcycle and a woman who took him to the hospital, implicate an LDU soldier.

At about 10:00AM on July 7, 2020, Ssenyonga borrowed a motorcycle and headed to a nearby trading center, a friend who was with him on the motorcycle said. The friend (who asked not to be named) said Ssenyonga asked that they go together and he accepted.

They rode less than two kilometers before meeting two LDU soldiers at a checkpoint.

“They stopped us. Ssenyonga reduced the speed and when he was about to stop, the LDU soldier hit him on the head. He may have thought that we were going to run,” Ssenyonga’s friend said.

Both fell down, the friend said. Ssenyonga hit the right side of his head and arm on the tarmac, while the friend sustained injuries on the knees and elbow.

“The LDU who remained on the roadside told his colleague that he had done a bad thing, which is out of order,” the friend said.

The gun’s butt stock was damaged. Three people interviewed by this reporter challenged the army to show the gun that the LDU soldier had. The spokesperson for the LDUs, Bilal Katamba, said the gun broke because Ssenyonga rammed into the LDU.

“We are still investigating the incident. And because of our seriousness, we are still detaining the soldier until investigations are complete,” Katamba said when he was told of the witnesses’ accounts. Katamba did provide details of where this soldier is detained. He is uncertain when investigations will be completed.

Ssenyonga’s friend said he was interviewed by officials from a government human rights organization. An official handling the case refused to comment. Doctors at a hospital where Ssenyonga was first examined also declined to be interviewed, saying they did not want to be involved in a “controversial” case.

Ssenyonga’s mother, Nakyanzi, wept in an interview, calling her son her last hope. The mother was fond of “Hello, how are you, Mum?” calls from Ssenyonga, the last coming on the morning of the day he sustained fatal injuries. Ssenyonga also regularly sent his mother money to buy food and other basic needs.

“Robert had promised to make life better for me. It pains me a lot to see the promises shattered. They are no more,” she said. She is uncertain “if government can fulfill all that my son had thought to do for me in the coming years.”

More than a dozen relatives and victims of LDU soldier human rights abuses during the pandemic shared similar stories of tears, pain, and a sense of injustice.

Presented as a panacea to insecurity in urban areas when they were recruited in 2018, Local Defense Unit soldiers in Uganda have been at the forefront of human rights abuse allegations during the implementation of coronavirus curfews and restrictions. Between March and mid-July 2020, when Uganda registered the first coronavirus death, LDUs and other officers were accused of killing 12 people. Six were allegedly killed by LDUs and five deaths were blamed on security agencies.

It’s not unheard of for civilians to die at the hands of security agencies. More than 50 people were killed by security agencies following spontaneous protests in November 2020 after the arrest of pop star-turned-politician Robert Kyagulanyi (aka Bobi Wine), who attempted to unseat Uganda’s president, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni. The president, who has been in power since 1986, promised an investigation into the killings.

Promises Made to be Broken

Mariam N. (whose last name has been withheld for security), 37, a resident of Mityana district, 43 miles from Kampala, said she did not receive the medication that army representatives had promised to deliver. “We meet soldiers at the district. They registered our names, promising that they will take us for treatment. Since then, we have never heard from them,” she said. Mariam said she was beaten by LDU soldiers while returning from a clinic to buy medicine. As she displayed the scar from a wound she said she sustained in the beating, she said she could still feel pain in her left leg and back.

Francis Ogwang Munu, 65, a resident of Oyam district, 169 miles north of Kampala, was severely beaten by LDU soldiers in June 2020. He died hours later. This is the only LDU murder case that was expeditiously prosecuted in the army court. The soldier was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. The family says imprisoning the offender is not enough. For his family, justice will not be attained without compensation.

“We don’t know where these soldiers are being imprisoned,” Munu’s brother said. “We, as lay people, could not follow them to see if they are in prison.” If there is to be justice, he said, “government must compensate for the death of Ogwang Francis,” who was a father of 13 children. The culprits were charged with a criminal offense that does not permit compensation. To pursue compensation, the family must file civil litigation.

“What pained and still pains me,” Aloyo Hadija, 43, a fruit vendor in Kampala, said, was being clobbered by LDU soldiers. She had been among a group of traders permitted to continue operating when Museveni announced a total lockdown in March 2020. She was beaten on the first day of the implementation of a total lockdown. The images of women yelling while defenselessly being beaten gripped the nation and caused an immense uproar. The head of Uganda’s army apologized, calling the handling of women “high-handed, unjustifiable, and regrettable.” But it was just the beginning.

When LDU Soldiers Became a Menace

The army said it had been keeping records of human rights abuses by LDU soldiers. These included five cases of death, according to documents shared by the deputy army spokesperson in October 2020. This list, however, does not include a motorcycle rider gunned down by an LDU in Masaka, 130 kilometers south of Kampala. He was riding with a woman, who was suspected of having an affair with the motorcycle rider. She was the wife of the LDU soldier. The motorcycle rider was killed by the army after refusing to surrender.

Other abuses registered by the army, according to documents from the deputy army spokesperson, include 14 cases of assault, one of threatening violence, and one of damaging property with menace. The army records show that 31 soldiers have been prosecuted for these cases.

Ugandan human rights lawyer Nicholas Opiyo says these cases are a tiny proportion of the abuses that might have been committed by LDU soldiers. There is no organization that has tracked or created a database of abuses as they occurred in Uganda.

There remain video clips of human rights abuses shared on social media that have not been investigated. For instance, a woman falling off a motorcycle after allegedly being beaten by an LDU was posted on Facebook. The army said it has failed to identify the soldier in this incident. “We are still investigating where it was exactly,” Katamba said.

Social media, Opiyo says, is a powerful tool that enables anyone with internet access to capture and share evidence of human rights abuses. He says those sharing information should provide credible evidence for prosecution. “Those of us who defend human rights rely on credible information. If you’re posting an attack by LDU, let it be credible. Provide names of places, names of individuals and time so that we are able to respond.”

Curbing Crime

Starting in August 2018, LDU soldiers were recruited to curb rising crime in urban areas, especially murders and kidnappings. “When you’re patrolling and fighting crime, you’re working at night when most people are at their homes asleep. You interact with few people,” Katamba, the LDU spokesperson, said. LDUs had been trained to operate at night until the implementation of coronavirus lockdown measures made it necessary for them to operate during the daytime and brought them in closer contact with the population, the army argues. The army pledged to do better, but cases such as the beating of Francis Ogwang Munu and the Robert Ssenyonga incident happened months after numerous promises were made.

If evaluated on fighting crime, which they were recruited to do, the army says, LDU soldiers have performed well. “To our biased evaluation, they have performed beyond expectation. We must give them credit for that performance,” Katamba said. LDU soldiers arrested 5,808 suspects in the Kampala metropolitan area between May and December 2019, the first year of their work.

Between March and September 2020, the LDU soldiers arrested 1,693 suspects while they were implementing coronavirus lockdown regulations.

The army also recorded 79 incidents when security personnel were attacked by residents between March and June 2020, highlighting the perilous situations they often encounter. Residents often pelted stones at soldiers, according to army documents.

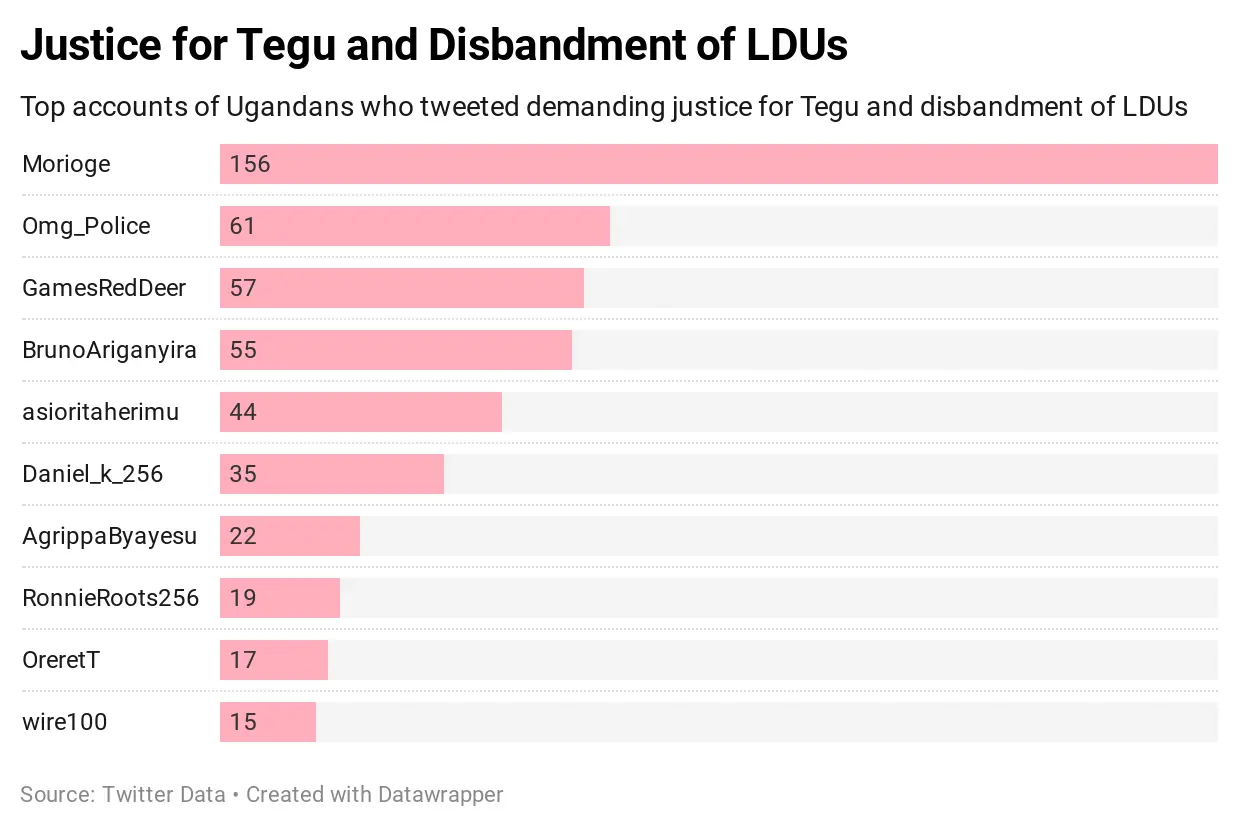

A tipping point ensued following the death of a university student, Emmanuel Tegu. The family claimed he had been beaten by LDU soldiers while sauntering home at night in early July 2020. However, surveillance camera footage revealed Tegu was not beaten by LDUs and that the accusation was false. He was beaten by a private security guard who was guarding a bank. As an enraged public demanded justice for Tegu on social media, they also demanded the disbandment of LDUs. The soldiers were recalled for a short refresher training on human rights less than a fortnight after incessant disbandment calls.

LDU soldiers have since been redeployed to execute their core mission of fighting crime at night. For those still calling for their disbandment, Katamba says, “LDUs cannot be wished away.”

Ignorance and Fear

The pursuit of justice calls for victims or their relatives to file complaints, provide supportive evidence, and follow up on case progress. After interviews with this reporter, more than half a dozen victims and relatives hastened to ask for advice on how and where to register complaints. Others were clearly scared. A relative of Munu, who was allegedly killed by LDU soldiers, has been calling to ask whether this reporter has accessed useful information that can help the family in pursuit of compensation.

Victims fearful of retribution have chosen to remain silent. “You see someone with a gun—I can’t attempt to compare myself with such a person. I have no power and there is nothing I can do,” Christine A. (whose last name has been withheld for security), 48, a fruit vendor in Kampala said. She reluctantly accepted to be interviewed, claiming that a soldier had warned her to shut up.

Mariam, who says she was beaten by LDU soldiers, said she has not filed a case in court because of fear. The dilemma these victims are enmeshed in is a tell-tale of the dearth of free legal aid services in Uganda. It also speaks to the lack of knowledge about how to make use of available organizations.

Sylvia Namubiru, executive director of Legal Aid Service Providers (LASPNET), a consortium of various legal aid providers in Uganda, says a victim must start by filing a case or directing a free legal service provider to institute it. “You enter into a crime case on instruction, you can’t instruct yourself,” she said.

And the fact that victims don’t know how and where to find legal providers, Namubiru said, “confirms the fact that legal aid service is just a drop in the ocean” in Uganda. This predicament leaves injustice unserved and human rights abuses unchecked.

There have been fewer incidents involving LDU soldiers since their redeployment in late August 2020, following a short course on human rights. “We see a different approach to the new LDUs who are back on the street. They are more restrained,” Opiyo, the human rights lawyer, said. But communities that were assaulted don’t want them anymore.

“To me personally, even in the community, we can’t allow LDUs back. It’s still too early for the community to forget their brutal acts,” Tom Ayor, the clan leader in Oyam district, said. The community has lost too many of its own.