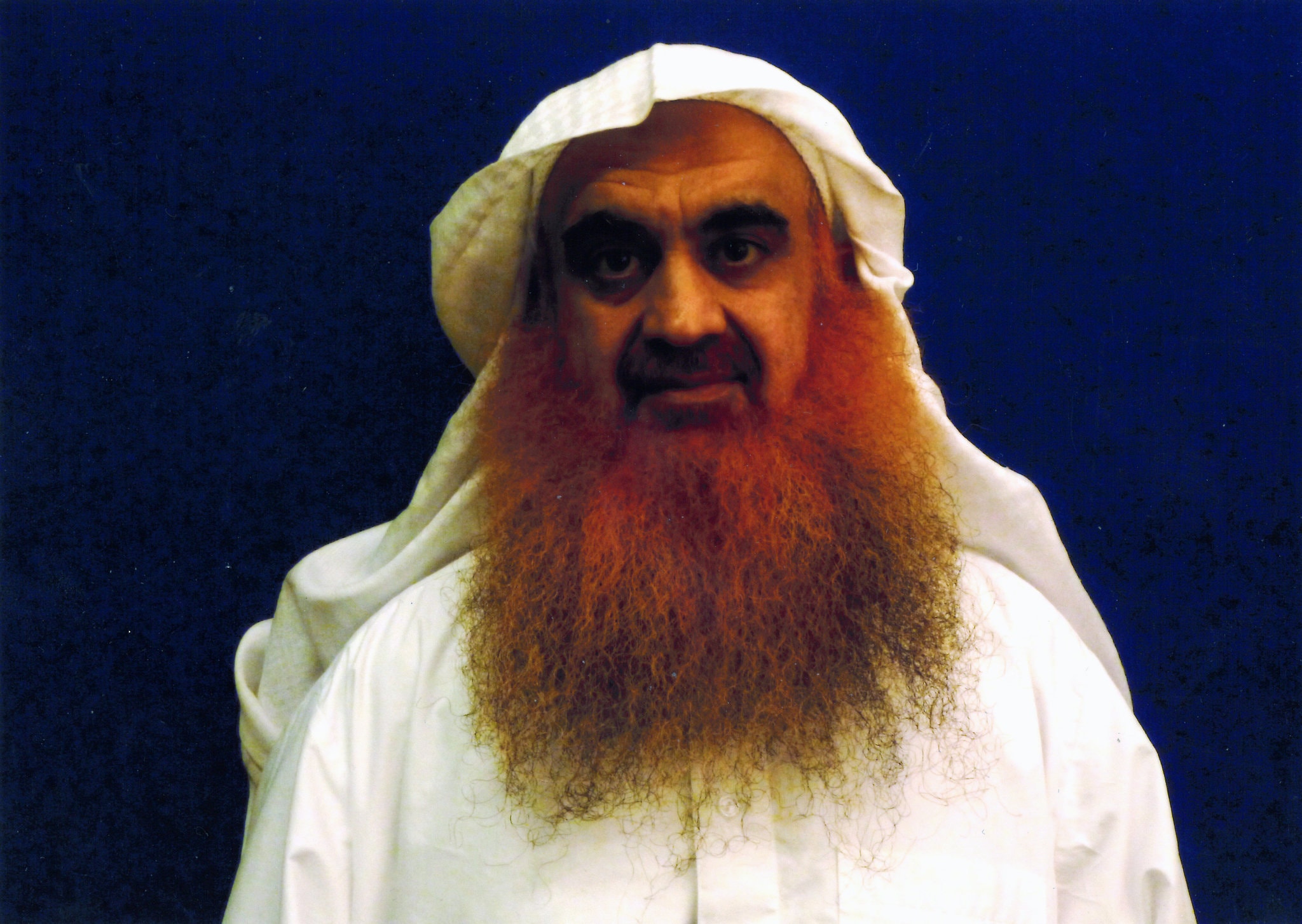

GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — By the time the C.I.A. delivered Khalid Shaikh Mohammed to the military prison at Guantánamo Bay in 2006, it had already extracted confessions from him through interrogations that included waterboarding, rectal abuse, sleep deprivation, and other forms of torture.

But none of what Mr. Mohammed said during his three and a half years in secret C.I.A. prisons could be used in the military commission trial where he would face on charges stating that he was the architect of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. So within months of his arrival at Guantánamo Bay, the Bush administration had F.B.I. agents questioned him and other Qaeda suspects to obtain fresh, ostensibly lawful confessions. Prosecutors called the new interrogators "clean teams."

Now defense lawyers in the Sept. 11 case—which has been stuck in pretrial hearings since 2012 and will not go to trial before next year—are stepping up their arguments that those teams were not so clean after all.

They say that they have growing evidence that the F.B.I. played some role in the interrogations during the years when the suspects were in the secret prisons by feeding questions to the C.I.A., and that the C.I.A. kept a hand in the case after the prisoners were sent to Guantánamo. The result, they contend, is a blurring of lines that undercuts the assertion that the confessions extracted after torture could be legally separated from those given by Mr. Mohammed and his four alleged accomplices to the F.B.I. at Guantánamo.

The defense teams cite documents turned over to them under court order showing that the F.B.I. was involved in the case when the prisoners were being held by the C.I.A., from 2002 to 2006. Then, after President George W. Bush had them transferred to United States military custody at Guantánamo, the C.I.A. continued to control or influence the detention of Mr. Mohammed and the other men, the documents suggest.

The extent of the cooperation between the two agencies is a matter of dispute, some of it carried out in closed national security court hearings. But the intermingling of their work, defense lawyers say, means that the statements the suspects gave the F.B.I. should be ruled inadmissible.

The intensifying battle over the confessions, which prosecutors say are critical to their case, is just one way that the legacy of torture continues to shadow the effort to get justice for the 2,976 people killed by the Sept. 11 hijackings. And it highlights how the military commission system has struggled to decide complex legal disputes, leaving the case unlikely to be decided even by 2021, two decades after the attacks.

"The clean teams were a fiction from the very beginning," said Cheryl Bormann, the lawyer for Walid bin Attash, a Saudi-born man accused of serving as a deputy to Mr. Mohammed in the hijacking conspiracy. "There was no separation. It's all one big team."

The first public information about F.B.I. and C.I.A. collaboration on interrogations involving the five alleged Sept. 11 conspirators emerged in a December 2017 pretrial hearing that challenged whether one of the defendants, Mustafa al Hawsawi, was subject to trial by a military tribunal rather than a federal court. Mr. Hawsawi, a Saudi man who was captured in Pakistan in March 2003 with Mr. Mohammed, is accused in the joint capital trial of helping the hijackers with travel and finances.

Abigail L. Perkins, a retired F.B.I. special agent, said at the hearing that she had reviewed some of Mr. Hawsawi's statements to the C.I.A. before she interrogated him in January 2007 as a member of a clean team, four months after his September 2006 transfer to Guantánamo.

She also said that while Mr. Hawsawi was held incommunicado at the C.I.A. black sites, the F.B.I. fed questions to C.I.A. interrogators to ask their captives.

A partially redacted transcript of a national security hearing held last summer at Guantánamo also shows that F.B.I. agents questioned Mr. Hawsawi during his time at a C.I.A. black site but hid their affiliation from him. At that hearing, a prosecutor also disclosed that information the government had given defense lawyers to prepare for trial commingled F.B.I. and C.I.A. information that came from the Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation Program, the formal name of the black sites, leaving the impression that it had all come from the C.I.A.

Prosecutors say the F.B.I. agents who questioned the terrorism suspects at Guantánamo in 2007 did so independently of what happened during the period when the defendants were tortured.

Even though the United States government "put together the aspects of law enforcement, intel, and military, for the purpose of gaining information, and ultimately obtaining a criminal case against these men in military commissions," Ed Ryan, one of the prosecutors, argued in court, the work of the clean teams is "legally defensible" because of the magnitude of the government investigation in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks.

Whether to accept the prosecution's argument will be for the new trial judge, Col. W. Shane Cohen of the Air Force, to decide.

Last summer, the first trial judge, Col. James L. Pohl, forbade the use of the F.B.I. interrogations at Guantánamo Bay then retired from the Army. Another prosecutor on the case, Jeffrey D. Groharing, called the 2007 F.B.I. interrogations "the most critical evidence in this case" and persuaded an interim judge, Col. Keith A. Parrella of the Marines, to reinstate them.

Now the new judge, who took over the case in June, plans to consider again whether each of the five defendants' F.B.I. interrogations should be admissible. Hearings on the question could start in September and run until March 2020.

First, however, the judge must decide the delicate question of how much testimony to take from former black site workers, including agents and contractors whose identities the C.I.A. is shielding by invoking a national security privilege. The defendants want the judge to hold an exhaustive hearing on what went on in the C.I.A. prison network between 2002 and 2006 as a basis for deciding whether the clean-team statements are admissible.

In June, James Harrington, a lawyer representing one of Mr. Mohammed's co-defendants, scolded Colonel Cohen at the judge's first hearing for referring to the F.B.I. interrogations as "cleansing" statements.

"Right now before the court I believe is an issue of voluntariness with respect to those statements," he said.

Mr. Harrington offered a longstanding defense argument that anything Mr. Mohammed and the other suspects said at Guantánamo was essentially "a Pavlovian response" drilled into the defendants in their three and four years of torture at the black sites, where the lawyers contend that calculated abuse trained the defendants to later tell the F.B.I. agents what the C.I.A. had forced them to say.

That was the general defense approach until December 2017, when defense lawyers started seeing both classified and unclassified evidence they say demonstrates that the United States government was engaged in "one continuous course of conduct to obtain statements by torture and other cruel and inhuman, degrading treatment, including incommunicado detention," according to James G. Connell III, a lawyer representing another defendant, Mr. Mohammed's nephew, Ammar al-Baluchi.

In 2017, for example, the lawyers learned for the first time that the C.I.A. had a role in how the F.B.I. agents would conduct clean-team interrogations.

The F.B.I. agents were required to write up their interviews not on a standard Federal Bureau of Investigation 302 form, the stock in trade of bureau record-keeping, but as a letterhead memorandum on a C.I.A. laptop. The agents were instructed to segregate claims of torture and other C.I.A. mistreatment on a separate memo, meaning they were absent from the F.B.I.'s descriptions of confessions by Mr. Mohammed and the others at Guantánamo in 2007.

Notes from Mr. Hawsawi's interrogation helped reveal that he had earlier been held incommunicado at Guantánamo, when the C.I.A. operated a black site at the military base and hid its prisoners from the International Committee of the Red Cross, in 2003 and 2004.

"Our position is not that the C.I.A. engaged in torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment and then the F.B.I. did something different," said Mr. Connell, who has drawn up a list of 112 pretrial witnesses to try to prove his point. "Our position is that the United States, as a whole, had a plan, a scheme or a program—however you want to describe it—to obtain statements from Mr. al-Baluchi by torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment."