Since European contact, Egmont Key has played a role in nearly every major U.S. historical period. In the 1800s, the U.S. Army used Egmont Key to imprison Seminole captives, and historians have described conditions on the island as a concentration camp. Over the last decade, the Seminole Tribe of Florida has launched a robust investigation into this period of Seminole removal to piece together and better understand this little-known chapter. But the window to document that history is quickly closing.

On a gusty May morning, the 11 a.m. ferry departed Fort De Soto and headed for Egmont Key, a long sliver of an island at the mouth of Tampa Bay on Florida’s Gulf coast. Accessible only by boat, Egmont Key routinely attracts vacationing day trippers who are lured by the picturesque beaches and clear waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

The day is as idyllically Florida-in-the-summertime as it can be and, over the course of the hour-long boat ride, the ferry captains point out dolphins and manatees to excited visitors. The sun dances on the water, and the smell of sunscreen mixes with the salt air. A reggae remix of Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On” drifts from the boat speakers as passengers shuffle coolers and beach chairs.

As a wildlife refuge and state park, Egmont Key is largely undeveloped. There are no public facilities. There is a single house for the lone park ranger and a smattering of historic structures that harken back to the U.S.’s 19th century military history.

There’s no dock on the island, so when the ferry finally reaches Egmont Key, passengers disembark in the surf and walk through the water to the beach. It takes Quenton Cypress and Dave Scheidecker a moment to get their bearings.

“Wow,” Scheidecker said. “Where we are right now, is where the beach came out to,” he gestures to the lapping water in front of the boat.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, neither has visited Egmont Key since February 2020, and they are startled by the amount of coastline that has disappeared in just the last two years.

“It’s about 30 feet out, and then it’s about 5 feet height-wise,” Cypress estimated, describing the degree of shoreline lost since their last visit.

Cypress is a member of the Seminole Tribe of Florida and serves as community engagement manager for the Tribe. Scheidecker is the senior research coordinator for the Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Both lead the Tribe’s research on Egmont Key and have spent the last six years untangling details of a dark history. During the mid-1800s, Egmont Key was a stopover in the Trail of Tears during the Seminoles’ forced journey from South Florida to Oklahoma. The U.S. Army used its base on Egmont Key to imprison Seminole captives during the Seminole Wars.

“It turns out Egmont Key checks every single box of [what constitutes] a concentration camp,” Scheidecker said. “The only thing is it’s older than all the ones that were recorded by the people who study concentration camps.”

Over the last decade, the Seminole Tribe of Florida has launched a robust investigation into this period of Seminole removal to piece together and better understand this little-known chapter. But the window to document that history is quickly closing.

Egmont Key has lost 50% of its land mass since 1875. Combined impacts from sea level rise, dredging from Tampa Bay shipping channels, and encounters with hurricanes and tropical storms are rapidly eroding the island. Visceral examples of this loss are easy to come by: Today, remnants of the iconic 1800s-era gun batteries that used to sit comfortably in the island’s interior are now nearly submerged in the ocean, some 600 feet offshore. And researchers worry that a mass grave on the western end of the island has already been washed away.

The island’s disappearance would also be a major loss for the wildlife that lives there. Egmont Key is home to as many as 117 species of birds, including bald eagles and wintering piping plovers, a small threatened shorebird with a distinctive black stripe across its forehead. Loggerhead sea turtles, a federally listed threatened species, nest on the island’s beaches, and Florida’s threatened manatees are regularly seen traversing the refuge’s waters.

In 2017, the Florida Trust for Historic Preservation highlighted Egmont Key as one of the most threatened historic properties in the state. It’s the first to be recognized as such due to threats of climate change and sea level rise. And given the dire predictions, as the island continues to slip into the sea, those who care about the future of the island have to decide — what can we save and how do we save it?

“A Palimpsest of Hundreds of Years of Activity”

Egmont Key was named in 1763 for John Perceval, the second Earl of Egmont and a member of the Irish House of Commons. Since European contact, Egmont Key has played a role in nearly every major colonial and U.S. historical period.

“Egmont is very much a palimpsest of hundreds of years of activity,” said Paul Backhouse, senior director of the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Heritage and Environment Resources Office.

Archaeologists sometimes use the idea of a palimpsest to describe the multifold significance of a site, where they can find historical evidence relating to many different time periods. Egmont Key’s lighthouse was erected in 1858 to guide ships through the shifting sands and treacherous waters of the Gulf. The Union Navy bested Confederate troops and took control of the island during the Civil War. Journalists and historians have likened turn-of-the-century Egmont Key to a bustling town, due to its hospital, bakery, numerous shops, churches, homes, soldier barracks, and Fort Dade, which the U.S. constructed in anticipation of the Spanish-American War. And during World War II, Egmont Key was a base of operations for the U.S. Army, Navy, and Coast Guard.

Much of this U.S. military history is well documented for island visitors in signage, and iterations of many historic structures still stand. But what is not at all apparent is the vital Seminole history imprinted here.

That’s something the Tribe is working to change.

In 2012 and 2013, the Army Corps of Engineers consulted with the Tribe to review its upcoming projects. The Corps planned to renourish parts of Egmont Key’s shoreline by adding sand to replenish loss from erosion, and they wanted to gauge the Tribe’s interests or concerns.

“There was something about Egmont that I remembered reading about in a book,” Backhouse said, remembering the first meeting. A faint bell went off in his head. “I was like, ‘Yeah, hang on. Can we get back to you on Egmont Key?’”

Backhouse and his research team looked back at historical records and found Tribal connections to Egmont referenced in the 1850s, towards the end of the Seminole Wars. “That was kind of how this whole thing started,” he said. “Because it raised more questions than it answered.”

Miccosukee speakers know Egmont Key as a Yanh-kaa-choko, or an island that is distinct from their home islands in the Everglades. Tribal records show that Florida’s Indigenous peoples used Egmont Key as an important fishing site spanning generations.

"When we had the Trail of Tears, I always wondered, how did ours start? Did we walk all the way through Florida?"

Quenton Cypress, community engagement manager for the Seminole Tribe of Florida

But when President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, state and federal governments moved to dispossess Indigenous peoples from their native lands in the South. In what became known as the Trail of Tears, tens of thousands of Indigenous peoples from across the southeastern U.S. were forcibly relocated to reservations in the American west. Thousands died during the journey.

In Florida by the mid-1830s, the Seminole had already been forced from their historic lands and pushed to the Okeechobee and Everglades region of South Florida. U.S. historians recognize the anti-Indigenous military efforts in Florida as the Seminole Wars, which lasted from 1816 to 1858. But the Seminole make no such distinction: the Tribe understands their entire relationship with the U.S. government up to that point, as well as beyond, as an uninterrupted continuum of American aggression.

It was during this period that the once ancestral fishing site transformed into a stopping point in a painful journey of removal. The Tribe estimates that thousands of Seminole were marched or shipped from Florida north along the Gulf of Mexico to the Mississippi River, where their westward journey to Oklahoma continued. At least 300 Tribespeople were imprisoned on Egmont Key.

“When we had the Trail of Tears, I always wondered, how did ours start?” Cypress said. “Did we walk all the way through Florida?”

Cypress belongs to the Wind Clan and grew up on the Big Cypress Reservation. For him, this research on Egmont Key has revealed new and important details about his cultural heritage.

“[It] helped answer the questions that seemed obvious, but really weren’t obvious if you didn’t ask — of how the Indian Removal Act worked for us, and why do I have cousins in Oklahoma? That is why. People from my clan are over there.”

The Miccosukee word Pet-Elee-Ke, meaning “death boat,” describes the steamships like Grey Cloud, which were used to transport the Seminole north. Grey Cloud stopped along islands in the Gulf of Mexico, including Egmont Key, where the Seminole were held by the U.S. Army in an internment camp. Army records refer to the site as “The Indian Depot at Egmont Key,” but Seminoles remember it as a prison and concentration camp, often referring to it as “The Dark Place” and “Our Alcatraz.” At least six Seminole died and were buried there, in graves labeled “Unknown Indians.”

“The second time we did a big tour [of Egmont Key for Tribal members], it was for people from the Brighton reservation for the most part,” Scheidecker said. “One of the women there who I’d been talking to when I was talking about the incarceration, she said, ‘You realize you’re making us mad, right?’” Scheidecker remembers telling her, “‘Good. You should be.’”

Backhouse said one response to this research was shock — for some Tribal members, this was the first they’d ever learned about Egmont.

It is “a story that was so suppressed in the history books,” he said, “and it really became a focal point for the community, for this office. It was a pivotal moment for the office in thinking about what we do, the service that we provide, and how we protect stories and amplify stories that need to be put back out.”

A Testament to Survival

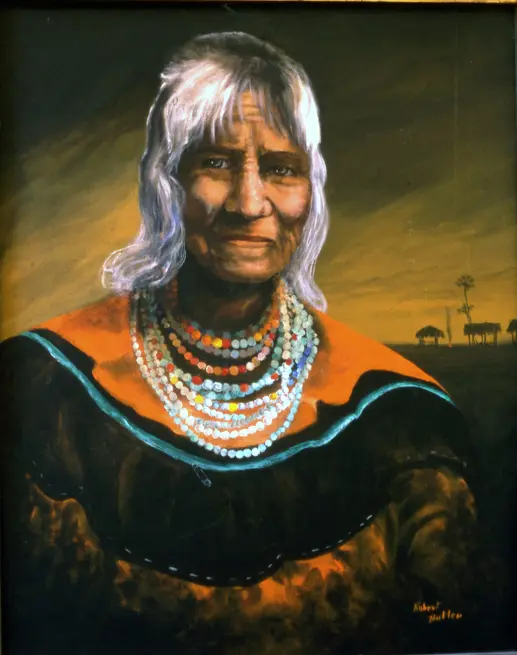

Yet while Egmont Key is a reminder of a history of oppression, the island is also a testament to Seminole survival. In one stage of Seminole removal in 1858, 160 Seminole were captured and transported to Oklahoma. One Seminole woman aboard managed to escape when the ship stopped to refuel in St. Marks in Florida’s panhandle. Under the guise of gathering medicinal herbs, Polly Parker (also known as Emateloye, her birth name), led a small group back to Seminole territory near Okeechobee, traversing more than 300 miles south.

“It’s a pretty tremendous story of escape that gets compounded in importance,” said Andrew Frank, a professor at Florida State University who specializes in the history of Florida Seminoles and the Native South.

“She’s part of this public-facing Seminole community in the early 20th century,” Frank said. “I would guess that there are very few Indigenous women in the 19th century that we can trace over more than a couple of years.”

Parker’s walk back to South Florida is a key piece to why she is well recognized and celebrated by the Tribe. Members of the present-day Tribe are descended from Indigenous peoples who lived in Florida, Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Mississippi for more than 12,000 years. The Seminole Tribe of Florida became federally recognized in 1957 and is today comprised of some 4,200 members. Many live on six reservations across Florida, including in Hollywood, Big Cypress, Brighton, Fort Pierce, Immokalee, and Tampa.

Numerous Tribal members today proudly trace their lineage to Parker, who is understood to be the matriarch of “an astonishingly large number of chairmen, councilmen, board members, [and] elder women of prominence,” Frank said. During the Indian removal era in the 1800s, there were likely less than 300 members of the Seminole Tribe still in Florida, and Parker may have been only one of only a dozen or two Seminole women of childbearing age. She died in 1921 at over 100 years old.

"People didn’t talk about it or didn’t pass it on. So, so much history was lost. So it was our job to try to go through and find anything we can about this lost history."

Dave Scheidecker, senior research coordinator for the Tribal Historic Preservation Office

In 2013, Tribal members recreated Grey Cloud’s journey from Egmont Key to St. Marks to commemorate the power of Parker’s legacy.

“If it wasn’t for Polly Parker making it back to Okeechobee, we wouldn’t be here,” Norman Bowers, one of the voyagers, told the Tampa Bay Times during the memorial trip.

As culturally meaningful sites like Egmont Key shift along Florida’s changing coastline, Frank said the ways the histories of those places are remembered can shift, too. When historical sites are no longer accessible, the stories that those places hold can slip out of society’s consciousness as well.

“Let’s Get that Story out There”

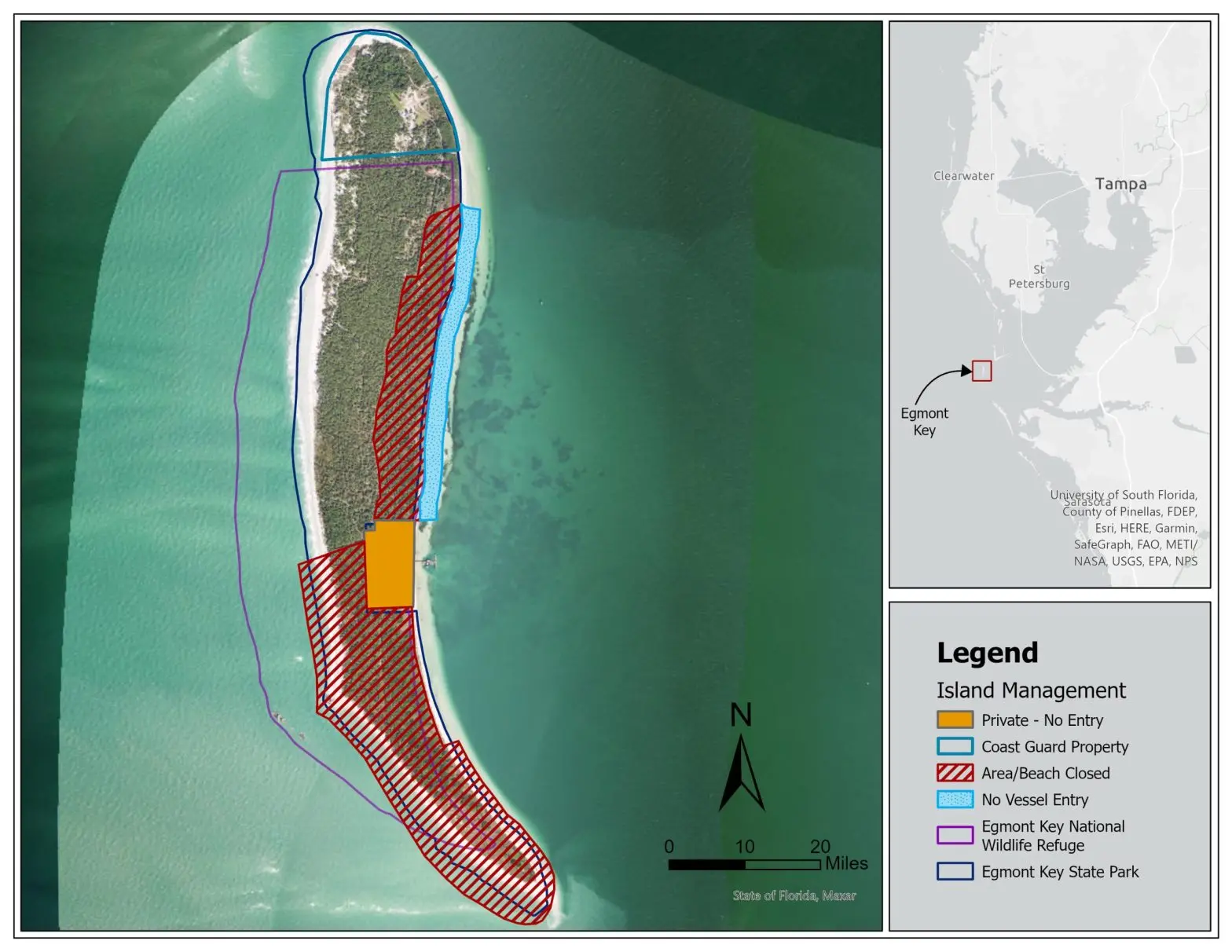

Egmont Key is owned by a mosaic of federal and state agencies with overlapping boundaries segmenting the island. Management of the island is shared by the Division of Recreation and Parks within the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Coast Guard. The island is also located within the boundaries of Hillsborough County.

This combination of federal and state agencies has the decision-making power in how the island is ultimately managed, but the agencies and individuals who have a stake in the island’s future are even more multifaceted — and disagreements on whether to save the island can be seen even among Tribal members.

Today, Egmont Key attracts some 200,000 visitors annually, which researchers and historians consider an opportunity to introduce this Seminole story to people who aren’t aware of its significance. But there’s a tension between the island’s marketed beachy-vacation vibes and its suppressed history.

“It’s weird,” Cypress said. “You don’t see people going around to Holocaust [memorials] and dancing and hanging out, having a good time [in] bathing suits, taking nude photo shoots.” He added, “essentially on a place where people were killed and murdered. And I’m not saying they’re being disrespectful, they just don’t know. But if they did know, they would think about what they’re doing.”

After representatives from the Tribe first consulted with the Army Corps of Engineers about Egmont Key, surveys, site visits, and archival research ramped up. Backhouse said it quickly became apparent they would need to bring the Tribe’s spiritual leaders out for guidance.

"As a Seminole, it was important to me to visit Egmont Key so that I could experience the place where many of my ancestors were unwillingly held."

Aaron Tommie, member of the Seminole Tribe of Florida

“It was a question that we’d never really faced at the time,” Backhouse recalled. “This island’s going underwater. There’s obviously a story here, and we need to kind of start unpacking it. But [does the Tribe] want that story preserved? Do they want the island preserved? Do they want to let this go? Because it’s kind of a sad story. All these questions started arising.”

Scheidecker said that much of the Tribe’s history is passed down through oral histories, but the stories about Egmont Key were sometimes incomplete, having left with survivors en route to Oklahoma or willfully forgotten.

“People didn’t talk about it or didn’t pass it on,” Scheidecker said. “So, so much history was lost. So it was our job to try to go through and find anything we can about this lost history.”

To corroborate what information they did know, researchers combed historical collections for any existing information that could fill in the gaps of this fragmented history. Cypress made his first visit to the island in 2016.

“That’s what I’ve always been interested in learning, not just more about a history but learning more about myself,” Cypress said. “Where I come from as a Tribal member and being able to give that back to my family.”

The Tribal Historic Preservation Office recorded oral histories with elders and conducted an archaeological survey in 2016, after a lightning strike on the island ignited a fire, burning and opening nearly 80 acres for study. From that work, archaeologists believe the internment camp was sited near the center of the island, close to what is now a dilapidated U.S. Coast Guard helipad.

Comprehensive findings from the Seminole Tribe’s research is detailed in “Egmont Key: A Seminole Story,” a digital 44-page report that draws on research, memories, graphics, photography, and interviews. The Tribe has also used this study to inform educational curricula, which meets Florida education standards.

While research continues, the priority for the Tribe now is amplifying this story.

“That’s absolutely the instruction that we’ve been given is, ‘let’s get that story out there,’” Backhouse said.

“Preservation is culturally contingent,” Backhouse said. “And it should be.”

Researchers at the University of South Florida are currently developing interactive and multimedia materials for the Tribe that can tell the story of Egmont Key and allow users to virtually experience its history.

Prototypes will be installed at the Seminole Tribe’s Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum in Big Cypress, among other possible locations. Cypress and Scheidecker also take Tribal members to Egmont Key to connect with this history on a personal, spiritual, and cultural level, while the island is still accessible.

“As a Seminole, it was important to me to visit Egmont Key so that I could experience the place where many of my ancestors were unwillingly held,” wrote Tribal member Aaron Tommie, reflecting on his visit to the island in “Egmont Key: A Seminole Story.” “I became enraged and saddened when I learned of the terrible events that happened on the island. One could only imagine the fear and confusion my ancestors lived with as they awaited uncertain futures, a far cry from the freedom they were accustomed to.”

For THPO, Egmont Key is a turning point.

In an article for the Society for American Archaeology Record, Backhouse wrote that “THPO works in unison with the Tribal government and Tribal communities to protect and preserve a collective and fragile past.” The multifaceted questions Egmont Key stirs up challenges how and what preservation might — or can — mean for the Tribe moving forward.

“Internally, it made us really think about how we go about preservation,” he said. “In this case, the physicality isn’t quite as important as the remembering of the story. So ‘preservation’ is a preservation of memory and of historical narrative more than it is preservation of physical space.”

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative founded by the Miami Herald, the South Florida Sun Sentinel, the Palm Beach Post, the Orlando Sentinel, WLRN Public Media, and the Tampa Bay Times.

This series was supported by the Pulitzer Center’s Connected Coastlines Initiative and the Delores Barr Weaver Legacy Fund at The Community Foundation for Northeast Florida.