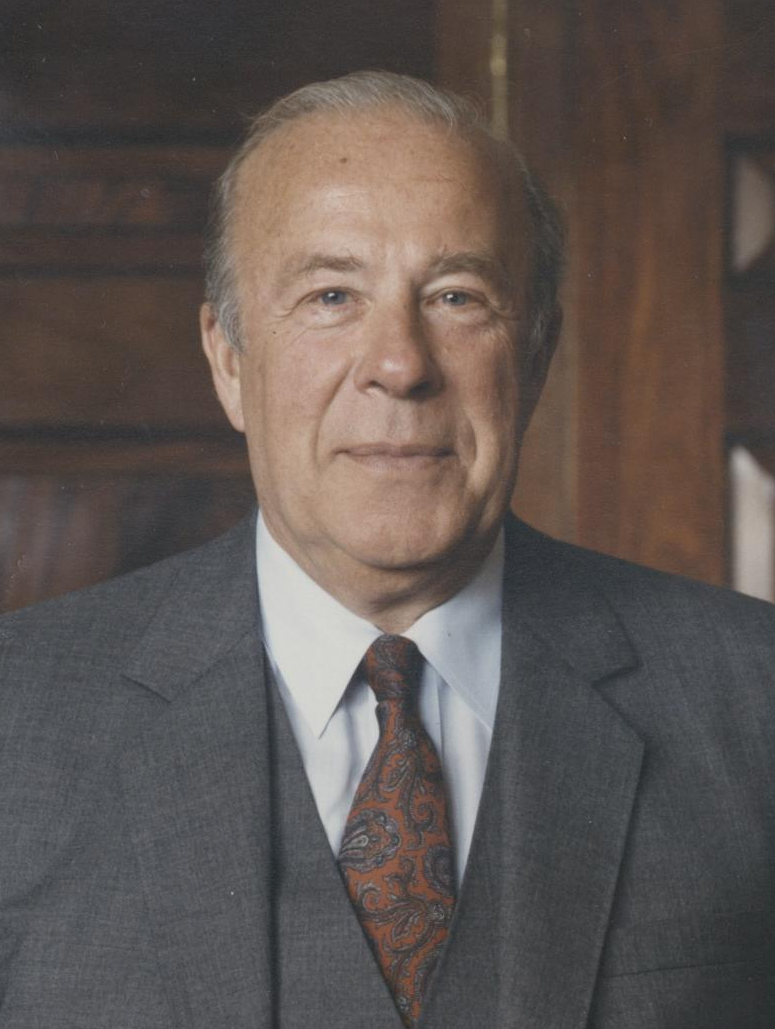

In March of 2013, I visited George P. Shultz in his office at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Ninety-two years old, he received me in a well-tailored suit with touches of bright color that matched the California weather. Around his desk were many framed citations, awards, and letters from colleagues and dignitaries, including President Ronald Reagan, under whom he had served as secretary of state. We spoke for more than an hour.

Mattathias Schwartz:

This story is about our current policy in Central America. It's also about the history of the whole drug war. I think that I'm going to put some special focus on the Reagan period. I read with great interest the report of the Global Commission [on Drug Policy], which you were the chair of. And this is a great summary of all the data that suggest our current policies aren't working, and some ideas for what the new policies might be.

What I'm interested in hearing more about is, well, it seems like we've known for a while that our current strategy doesn't work. I'm interested in what has sustained it for so long—why we've stuck with it. I know this talk that drugs, particularly the legalization of drugs, is a taboo subject in policy circles. And that there's a certain amount of bureaucratic inertia. But I also feel like there must be some other interest, which the current prohibition type of policy is serving. I was hoping you could give me some insight into that. What has kept us on this track for so long when there's been so much feedback that this is not working?

George P. Shultz:

One reason … we haven't felt the full effects of it ourselves. It took us 12 years to learn that Prohibition wasn't working. There was Al Capone, there was the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre. The violence was here. Now we have outsourced the violence, in effect, to Mexico and Guatemala and Honduras. And earlier, Colombia.

I think the idea of denial never worked. I remember in the Nixon administration, Pat Moynihan was counselor in the White House. And he was a kind of self-appointed drug czar. The idea was to cut down on drugs in this country by keeping them out. And I'm riding up to Camp David with Pat one time, and I have to give a presentation and I'm studying my notes. Pat's in a state of exuberance. And he interrupts me and says, "Shultz, don't you realize? We just had the biggest drug bust in history." And I say: "Congratulations." And I went about my … and he says, "But this was in Marseille! We've broken the French Connection. And I say, "That's great." And he pauses and says: "Shultz, I suppose you think that as long as there's a big profitable demand for drugs in this country, there will be a supply." I said: "Moynihan, there's hope for you." We have never succeeded in keeping drugs out of the country.

MS: So this was something that you thought 30 or 40 years ago.

GPS: Now in the Reagan period, we had the war on drugs. But Nancy Reagan had really a different approach. She had her Just Say No program. She didn't get much help from the bureaucracy, but she kept at it.

MS: Which was more demand side. Education and ...

GPS: Towards the end of the administration, she made a speech at a U.N. body and I went with her. The drug bureaucracy was really opposed to her speech, because she said that the drug war starts in American cities, not in where you are, and we have to do a better job of getting control of demand if we're going to...

MS: And that was her U.N. speech, right?

GPS: This was at the U.N. And they all said that if you say that, Mrs. Reagan, we'll never get any cooperation from anybody. But she was stubborn. She believed what she believed. So you can get the text of her speech. And it's very moving. It was one of these places ... I went there, I sort of remember it well, because it was a U.N. body where you spoke from your seat. And then there was a pause where people could come around and speak to you. So I think she was supposed to speak about 11:30, and she asked me when we were supposed to get there. And I said: "11:15, plenty of time."

She said: "No George, I expect people to listen to me. I should go and listen to them."

So we got there around 10:15 and the place was deserted. She looked around and she says: "Doesn't anybody want to hear what I have to say?" And I say: "Nancy, the place will be jammed when it's time for you to speak." Me, not knowing anything. But it was. And she spoke. And then all these delegates came by and said: "Mrs. Reagan, it was so refreshing to hear you say that. And it only makes us more determined than ever, if the U.S. realizes that, to be helpful." In other words, it was exactly the opposite of what the bureaucracy had said.

MS: And when you say the drug bureaucracy, what are ...

GPS: All the people who are employed … it's a very extensive bureaucracy.

MS: It's funny, when you look at the history of the D.E.A., I wasn't able to find a classic bureaucratic entrepreneur like an Anslinger, or a J. Edgar Hoover. But then I was down in the [Hoover Institution] archives for a little while, earlier today, and it seems like Ed Meese had a real role in pushing interdiction and pushing foreign cooperation overseas as he did with the National Drug Policy Board, which seems like it was a real high level group, and then with [Operation] Blast Furnace and [Operation] Snowcap. Was there disconnect between Nancy's approach and his?

GPS: I don't know the answer to that.

MS: Okay.

GPS: But I know Nancy had her Just Say No campaign. And I remember this dramatic speech at the U.N. It was towards the end of our administration.

MS: Was there something about the drug war abroad that appealed to (Attorney General Edwin) Meese either as a person, or a policymaker?

GPS: You'd have to ask him. I don't know.

MS: Okay. And then what were your interactions with the D.E.A. like? I read most of your memoir. What were your interactions with the D.E.A. like during your time at State?

GPS: Not a lot.

MS: I read that at some point the D.E.A. took on a larger role in the Western Hemisphere and the C.I.A. took on a smaller one. Is that is a correct understanding?

GPS: Well, the C.I.A. was very differentiated from the narcotics people. I don't think it was a trade-off from one to the other.

MS: This is just history that I've been reading. I didn't live any of it. So this is just a hypothesis that I've been thinking about, that the drug war gave us a way to stay in Latin America, after Iran/Contra, with a greater degree of Congressional oversight than there had been before. But again. I'm curious, is that … because when I read the history from '84 to '86, Iran/Contra is happening, the major drug laws are being passed by Reagan, and then these initial foreign operations, led by the D.E.A., are getting underway. I'm trying to figure out if there's a causal thread running through all of them.

GPS: I don't recall well enough to be able to make a comment about it.

MS: Okay, okay. Let's see. So what was the initial motive for forming this commission [Global Commission on Drug Policy], that put all this research together.

GPS: Well, I believe it's a rising concern in Latin America that the United States policies on drugs are making governance in their countries more difficult, and are tending, also, to increase the use of drugs in those countries. Because the drug lords want to get kids hooked and be mules for them. So the existence of the big drug trade is a problem for many Latin American countries. Right now, I think Honduras is having an awful time with it. Guatemala has had a tough time. Mexico. They've had close to 60,000 deaths in the past five years from the drug war business. The money comes from the United States and the guns come from the United States. So I think this commission represents an effort on their part to say: "Look, be a good neighbor. You're making life difficult for us."

MS: The story about Moynihan was extremely interesting. I'm curious, you mentioned the drug bureaucracy. What's kept it going for so long? I read that in 1987 that someone from the D.E.A. said that cocaine availability could be halved in three years. And then they said it could be halved in ten years, in in 1990. It's never happened. But nevertheless, we continue these foreign supply-side...

GPS: Actually, according to the World Health Organization, the use of drugs is higher in the United States than most comparable countries. So you have to say that the war on drugs has simply not worked. It hasn't kept drugs out of this country. It hasn't caused us to have a lower level of use than other comparable countries. We have wound up with a large number of young people in jail, mostly blacks, a huge cost, and a debilitating one to our society. And big foreign policy costs.

MS:I'm trying to get a sense of why we've stuck with it. Particularly these paramilitary operations abroad where we try to get big seizures or do crop eradication, or the Andean strategy and Plan Colombia. Why is it that we keep going back, again and again, to this approach?

GPS: I don't know. But I know it's very hard to have a discussion in political circles. When I came back here from being secretary of state, I was invited to give a talk to some alumni gathering. And somehow, I made some comments about drugs, and somebody recorded it, and it wound up the next morning in the Wall Street Journal. And I was inundated with letters. Ninety-nine percent of them supported what I said, but three-quarters of the people who supported it said: "I'd never say anything like that, because I'd be ostracized." So there's a kind of inability to talk about it. The most poignant letter I got was from Jimmy Symington, which said: "Congratulations on your statement. I said something like that a few years ago and that's why I'm no longer a congressman."

MS: What is it that makes it so hard to talk about, and makes the backlash so strong, do you think?

GPS: I don't really fully understand it but I do think it's beginning to break open now. You're more able to talk about it. There's this commission. Paul Volker and I wrote an editorial in the Wall Street Journal that you may have seen. Basically saying: "Well maybe, finally, we're beginning to be able to talk about it. It's about time." And your magazine is going to write an article about it, so that's a plus.

MS: Looking at Peru, Bolivia and Colombia in the late 1980s and early 1990s, did they have any—did they have a strategic significance or importance to U.S. interests—other than the fact that they were supplying all this cocaine that was causing all of these problems domestically—did they have strategic significance as well?

GPS: Certainly. I always felt, and President Reagan always felt, that foreign policy starts in your neighborhood. If your neighborhood is in upheaval, you're in trouble. If you have a stable, prosperous neighborhood, you're better off. So my first trips out of the country were to Canada and Mexico. And we paid a lot of attention to Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, on the grounds that this is where we live.

MS: I read also that there were people in the administration who saw El Salvador and Nicaragua and Central America as a very serious threat. I think you quote Ms. [Jeane] Kilpatrick that there could be MiGs [fighter jets] flying out of Nicaragua in a matter of months.

GPS: Well, during the Cold War, Cuba was a Soviet base really. And they could fly surveillance missions from there. If they established themselves in Nicaragua they would go up the West Coast. And if they established themselves with an airfield in Grenada, then they had a way to go all the way to Africa. So these were strategic issues.

MS: And was there anything significant about the Andean countries strategically? I understand what you're saying about keeping things calm in one's own neighborhood. But was there anything strategically about those three countries that gave them an additional strategic dimension, other than the fact that they were the main suppliers of cocaine?

GPS: No, just what I said. They're our neighbors. It's very important, what's going on in our neighborhood.

MS: We've had this Soto Cano Air Base, which I was able to go to for a day, in Honduras, since 1984. So it's sort of a bitter irony that there's so much violence there now. Why is it that Honduras, which has been such a stalwart platform for U.S. operations over half a century, has never been able to prosper or achieve much of a level of internal security?

GPS: Well, I don't know the answer to that question, but it's a reality.

MS: I have some questions to ask you about the Cold War, too. I'm writing a second article for my friend's magazine about the Cold War, so I'd be remiss if I didn't ask you a little bit about that, if you don't mind.

GPS: No.

MS: So, I read at Reykjavik [the summit meeting of October 1986], that Gorbachev and Reagan, that they both said they wanted nuclear weapons to get to zero in ten years. But looking back, I'm curious what you see as some of the main reasons this didn't happen.

GPS: Well, if we had finally agreed, it would have been a revolution. I remember that when I returned from Reykjavik, Margaret Thatcher came immediately to Washington. And I was virtually summoned to the British Ambassador's residence. And, you know, she had a little handbag. And I learned there's a verb, in the British language, to be handbagged. Beaten up, with her handbag. I was handbagged.

"George, how you sit there and allow the president to agree to a world without nuclear weapons?"

"But Margaret, he's the president."

"Yes, but you're supposed to be the one with his feet on the ground."

"But Margaret, I agreed with him."

People were shocked and not ready for it. But it was a good thing, because we gradually are returning to that subject. Reykjavik was a turning point. The number of nuclear weapons in the world today is about a third of what it was at the time of Reykjavik. There's been a huge reduction.

MS: When I read the history of the Cold War, there are all these moments that read like they could have been turning points, [such as] when Stimson appeals to Truman, or the [Acheson-] Lilienthal Plan. Do you feel this arms build-up was inevitable given the technology and the ideologies of the two superpowers? Or were there points when it might have been headed off sooner?

GPS: Well, I suppose you can always identify them, but the reality is it didn't. It kept building. It wasn't until Ronald Reagan came along that it began to change. Ronald Reagan asked the Joint Chiefs, after about a year into his presidency, he said: "What would be the impact on the United States of an all-out Soviet nuclear attack on us?" And they came back, after a few weeks, with their response. Initial casualties, around 150 million. And subsequent, continuing casualties, because you know we'd have no infrastructure left … Would he retaliate? Yes. So I heard him say many times, "What's so good about keeping the peace by an ability to wipe each other out?" And that sentiment led to a statement at the first Reagan/Gorbachev summit in Geneva. The joint statement said: "A nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought." You can't win if both sides are wiped out.

MS: Yeah, no … it's terrifying to think of, even.

GPS: Exactly.

MS: Was there ever a point in the negotiations and summits when you were frightened that it might come apart and the two sides didn't see eye to eye? I'm sure there were lots of points like that, but do any of them stand out?

GPS: Well, in the period when Ronald Reagan and I were in office, we had a moment of testing of us and our allies. NATO had agreed that we would try to negotiate, in moderation, in the Soviet deployment of SS-20s, intermediate range forces. And if it was impossible, then we would deploy. Initially in Britain, Italy, and Germany. And Germany would deploy Pershing ballistic missiles. So we had this big negotiation all through 1983. And it failed. So we deployed. And it was quite a close thing. Particularly in Germany. But the Soviets then walked out of the negotiations. There was a lot of war talk. They tried to scare everybody to death. And it didn't work. So gradually, there was a kind of a backing off on their part. And by the summer of 1984, I went to President Reagan, who was down in Los Angeles. There was some meeting down there and I asked for some private time.

I said: "Mr. President, at I think around four of our capitals where we have embassies, at a cocktail party, a Soviet official has come up to one of our people and said almost exactly the same thing. Which boils down to, if Gromyko is invited to Washington, when he comes to the annual visit at the U.N., then he will accept. Now, you have to remember, Mr. President, that Jimmy Carter shut down everything after Afghanistan, including Gromyko's traditional visit. So you might want to think this over, because they're still in Afghanistan." He said, "I don't have to think it over. Let's get him here."

So that fall, in September, he [Gromyko] came. And it was a gigantic event. There was a little fun connected with it. Because Nancy Reagan and I had a good relationship. And we talked about it. And she was … [inaudible] … involvement, could she have, should she have.

I said: "The way these visits go, Gromyko comes into the West Wing, into the Oval Office, and we have a meeting. And we walk down the colonnade to the mansion. And there's some stand-around time, and then there's a working lunch."

And I said: "When he comes to the mansion, that's your house. So how about your being there, as the hostess?" So she agreed to that. So we come to the White House itself. And Nancy's there. Gromyko's a very quick diplomat. He immediately makes a beeline for her. And talks to her.

At one point he says to her: "Does your husband want peace?"

And she bristles. She says: "Of course my husband wants peace."

He says to her: "Well then every night before he goes to sleep, whisper in his ear, 'peace.'"

So he's a little taller than she is. She puts her hands on his shoulders and she pulls him down. So he had to bend his knees a little bit. She says: "I'll whisper it in your ear. Peace."

MS: [Laughter.]

GPS: But anyway, that is a turning … the Soviets blinked. And after the election, we set up arms control talks. Which I conducted in Geneva with Gromyko. What was interesting in December, we got a letter from Chernenko, who was then the secretary general. And in it he said, basically, we've been reading your statements. Reagan had talked quite a bit about a world free of nuclear weapons. It was not new at Reykjavik. He said, "it is not too late to find a world free of nuclear weapons." This was in Chernenko's letter. So we restarted the talks. This was when Chernenko was still the general secretary. Gromyko was still the foreign secretary. And then in the spring sometime, Gromyko was replaced by Shevardnadze, and Gorbachev came into power in the Soviet Union.

So there was a turning point before Gorbachev got there. But Gorbachev, I remember, when we went at the time of Chernenko's funeral, Vice President Bush was there, so he was the leader of our delegation. And I had a few things to say on behalf of the president. But mainly I had the luxury of being able to sit and observe. And here's Gorbachev. He just managed the funeral of the outgoing secretary general. He'd been meeting with heads of delegations for the past two days. We were one of the last. And he seemed fresh. He had a big pile of notes in front of him, which he shuffled around, and never looked at. A wide range of stuff came up, and he talked about it. Quick. Smart. And we were saying to our delegation, because I'd dealt with the Soviets way back when I was Secretary of the Treasury, this is a very different Soviet leader than any I've ever dealt with. He's much quicker. He's going to be a tougher adversary. But, I said, you can have a conversation with him. He listens. Responds.

MS: Oh, I'm just going to jump back to the drug track for one second … I was struck by that anecdote in your memoir about Gromyko, how you had to shout him down at that dinner in Geneva, when he was trying to sort of sabotage the agreement that Reagan had worked out in principle with Gorbachev. That was Gromyko also, right?

GPS: I don't remember that.

MS: Okay, okay. Oh yeah, so this discussion that you had with Moynihan in the car during Nixon's administration, and this view that you held even then that it was the demand and not the supply side of things that was really the root of the problem … were there points during your time as secretary of state when you found yourself fighting for that position? Because it seems like resources continued to be allocated to the supply side. So were there points where you fought, where you continued to fight against that?

GPS: I wasn't much involved with it. I supported what Nancy Reagan was doing. But I was so involved with the Soviets, and the Chinese, and Europe, and all these other things ...

MS: So you had an assistant—it wasn't called INL then, it was called the narcotics assistant secretary—were they the main person in dealing with drug efforts abroad?

GPS: I don't remember.

MS: This is such a tempting question to ask. What would you say the odds of a nuclear attack, Hiroshima-sized or larger, occurring at some point over the next hundred years?

GPS: Well, the way we're going right now, the odds are very high. Because Iran is on its way to getting a nuclear weapon. North Korea has a nuclear weapon. Pakistan has weapons, India has weapons. And when Iran gets a nuclear weapon, if it does, others will want them. There's more fissile material lying around, particularly enriched uranium. Which is much easier to make a bomb out of than plutonium. So I think it's a tipping point time right now. We need to get a hold of it. We had an article in the Wall Street Journal a couple of weeks ago about the present situation. Henry Kissinger and Sam Nunn and Bill Perry and I.

MS: I did read that. And that's the one where you called for total eradication. Or was it subsequent to that?

GPS: We've had several op-eds. This most recent one was about the current situation.

MS: I'm sorry, I keep jumping between the Cold War and the war on drugs. But let me ask you also about your [Global Commission on Drug Policy] commission report. So, I met with different folks from the D.E.A. for this story. I met with our ambassador from Honduras. I met with William Brownfield, who is our assistant secretary for INL right now. And what everyone keeps telling me, what everyone keeps saying is that, we do a lot of demand-side work, and we do a lot of civil society building, and we train police, and we do judicial reforms, but the hard-side stuff and the interdictions—that's not all of the equation, but everyone says it still needs to be a part of the mix. In the year-and-half or the two years since this report has come out, what kind of feedback have you been getting on these ideas? Have you seen Washington respond at all?

GPS: I think there's a stiff-arm from Washington. But gradually, I think, there's more willingness of people to discuss the issue. Because it's being realized how costly this war is, and how futile it has been. So we should reexamine it. And at least be willing to look at what some other people are doing, and consider a change. We're a long ways from that, but I think it's beginning to be possible to talk about. For example, legalizing may be too big a step for people, but you could decriminalize use and small-scale possession. Then people would be willing to come into a treatment center. Because they wouldn't be thrown into jail as a result of acknowledging that they're taking drugs. And the evidence in Portugal anyway, is that this doesn't help you much with older addicts, but with younger people it seems to be having some effect, and that's where you really ought to work. And when they decriminalized, they didn't have a big explosion of use at all. Not at all.

MS: Do you think interdiction, or crop eradication, do you think there is a role that that should play a role in our overall strategy?

GPS: Well, all I can say is that we've been doing it for forty years and it hasn't worked.

MS: I guess there are some who would say the problem would be even worse if we, if we …

GPS: [unintelligible] ... say anything. On the other hand, we haven't had a campaign against use remotely as strong as the campaign against smoking cigarettes. And that campaign has reduced smoking dramatically in this country. And there's no big effort like that, comparable to drugs, at all.

MS: So this story got started when I investigated an incident that happened on the Mosquito Coast, where the D.E.A. kind of bungled an interdiction, and four civilians were apparently shot and killed in a boat—it may not have been the D.E.A. who did it, it may have been the Honduran authorities who they were with—so I went and investigated that and I tried to find everything out that I could about it and get to the bottom of it, but I didn't realize that, that, that, that—uh, a lot of people find incidents like that to be more or less normal, or acceptable. Regrettable, but not … but not, scandalous. For that reason the story has kind of broadened into the history of operations like this. Of which there have been a lot over the years. And it seems like Blast Furnace was the first big one where we put D.E.A. people on the ground and had Department of Defense support and Black Hawks and did this big multi-agency thing. But I also get the sense that Blast Furnace was not a huge deal at the time. It wasn't a vast number of personnel, it wasn't a big amount of money. Do you have any memories of that operation getting underway? I know you had so much to focus on, and this one little thing in one corner of the world … I know Ed Meese is still around so maybe I'll reach out to him and he can tell me a little bit about how it got started.

GPS: He'll give you the tougher side. But there is a reality that you can't get away from. Namely, that it's been going on for forty years and it has not worked. That is a reality.

MS: It's so striking to me that twenty years ago we knew it didn't work, and how little it's changed since twenty years ago. And I can't ... I feel like there has to be some reason. And I don't know why it just—why it just keeps going and perpetuating itself, and I don't know what that reason is.

GPS: Well there's a common observation about government programs. You have to be very careful when you start one because they're practically impossible to stop once they get going.

MS: From where you sit, why is that?

GPS: Because a bureaucracy gets created and a pool of funds gets created and people in Congress get a stake in it, and there's a kind of interplay, and stopping it is hard.

MS: Was there a kind of turning point in the war on drugs when we decided to step on the gas?

GPS: Probably, but I can't place it in time.

MS: Okay, okay … let's see … it was interesting reading your memoir. You talk over and over again about the importance of separating intelligence from operations.

GPS: From policy

MS: From policy. Which was very interesting. And which made me think of the Iraq War and the Afghanistan War. Because that's a critique that people have leveled at those campaigns—that policy was driving or altering intelligence. Do you feel like the advice that you gave has been heeded? Or to what extent has it been heeded, this separation of policy and intelligence functions?

GPS: I'm not there, so it's hard for me to say. But, I think, if you look back, say, at the Iraq war. It was widely supported. Somehow there's the notion now, looking back, that it was Bush's idea and that he did it over everybody's objections. That's not true. The Congress supported it, the U.N. resolutions … it was not controversial at the time that it was undertaken.

MS: Although the intelligence that people were relying on when they made that judgment has subsequently become very controversial.

GPS: To a degree, although somehow it isn't reported that in the Duelfer Report, which was the definitive inspections report, Saddam Hussein had, he said, the experts and the equipment ready to go, on chemical and biological weapons, as soon as the surveillance stopped. So while they didn't find weapons, they found him ready to go with weapons once people got off his back. Somehow, that doesn't get reported. And it may very well be that some of the weapons got shipped to Syria, we don't know.

MS: And that, that's the Duelfer Report?

GPS: Yes.

MS: Okay. In your memoir you also talk about accountable people being within the executive cabinet chain of command, for operations happening abroad. I was wondering if you felt that was something that had gotten better or worse. And I appreciate what you're saying, that you're not there, and you don't know what you don't know.

GPS: It's gotten a lot worse. Because there are more czars in the White House than ever, overseeing practically every policy area, and they're unaccountable people. They don't stand for confirmation. They don't get called to testify. And it's partly a reaction, or it's an iterative process, because it's hard to get anybody confirmed for a political post. In the first place, if you agree to be an assistant secretary of something or other, you're confronted with a wad of paper to fill out. You say to yourself, particularly because you're told that if there's a mistake you're subject to criminal penalties, you better get an accountant and a lawyer. So finally you get that filled out and you get nominated. Then the Senate wants to know some more stuff. And finally, you get a hearing. And finally, maybe, you're reported out favorably. And any Senator can put a hold on your nomination. For any reason. And they do. And the reasons have nothing to do with you, at all. So after about eight months, finally, you get confirmed. And in the meantime, you're sort of in limbo. And a lot of people say: "To hell with it. I'm not going to go through that." So you lose the A-team, as a result. And that's a big loss.

MS: How's that an iterative process? Because the people who have made it through stay through, and they become the czars?

GPS: No, the czars in the White House are a response to the difficulty of getting anybody confirmed.

MS: Oh, oh. Because the czars don't have to be ...

GPS: Right.

MS: Because the czars don't have to be confirmed.

GPS: And once you're confirmed, people look at that and they say, "I'm not going to go through that process." It's demeaning. It's almost as though people say: "If you're willing to take a job in the government, there must be something wrong with you, and we're going to find out what it is and make it public." An easier way to do it would be a good thorough F.B.I. and I.R.S. check and say, "Look, if you've got a lot of skeletons in your closet, then don't come." And then proceed. Trust people to be honorable people who want to serve honorably.

MS: Were there random drug tests of federal employees during the Reagan administration?

GPS: No.

MS: Because I'm remembering that that was part of the 1986 [Anti-]Drug Abuse Act. But I might be mistaken.

GPS: Now there was an effort on the part of C.I.A. and D.o.D. [Department of Defense] officials to make everybody take lie detector tests as a method of management. And I opposed that. I said: "That's management by fear." You need to have management by trust. And while I was out of the country for a while, the people who wanted it managed to go to the president and get him to sign an executive order setting it up. And I remember I was asked on the trip and I wouldn't comment because it was a domestic matter. And when I got back, the first thing I was asked at a press conference was: "Would you take a lie detector test?"

MS: And you said "once."

GPS: I said "Once. Then I'm out of here." Because once you ask me to take a lie detector test then you're saying you don't trust me. If you don't trust me, I don't belong here. So all hell broke loose. And I went ... the president asked me over, and I said: "The policy you signed is not in accordance with the way you do things. Look, you've got a sign on your desk that says there's no limit to what a man can accomplish if he doesn't care who gets the credit. That's a management philosophy totally at odds with what these people have done. So he rescinded the executive order and my relations with the C.I.A. never recovered. [chuckles]

MS: It reminds me of something that one of your predecessors, Stimson, once said. That the best way to make a man trustworthy is to trust him.

GPS: There was a great skit early in the Eisenhower administration, at a Gridiron Club thing, where the reporters are joshing the powers that be. And people were trying to figure out where Eisenhower stood on this that and the other thing. And they couldn't find out. But they knew he liked to play golf. So in the skit, the reporters are interviewing his caddy. And they ask him: "How does he stand on anti-trust?" And the caddy says: "There ain't an ounce of 'anti' in that man. He trusts everybody." And I always thought, that's Eisenhower's magic. He trusts people and people trusted him.

MS: Yeah, no ... his military industrial complex speech was quite prescient also.

GPS: There's a new book about Eisenhower that gets into his presidency in detail. It's really very good.

MS: Oh really. What's it called?

GPS: There's two. There's a full biography. And there's another one called Ike's Bluff by Evan Thomas, focusing a little more on his presidency

MS: I know there have been a few things that I've asked you that were a little bit below your radar, because you were focusing on so many different things, but do you remember the conversations in 1984 about opening Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras, and why we needed it?

GPS: No, I don't remember that.

MS: Yeah, I figured that might have been one of these slightly lower-tier things. Going back to the czars. Who are they and where do you see their influence on our policy?

GPS: Somebody who is in charge of energy, or something. And they're in the White House. So presumably they see the President more than the cabinet officer does. So the cabinet officer winds up reporting to the czar. When I was in office I met twice a week alone, with President Reagan. And that was publicized. So people knew that I was on the President's wavelength.

MS: I was thinking more in terms of the use of special operations and covert operations abroad, that may go outside the cabinet's chain of command.

GPS: That's a different question entirely, the C.I.A.'s covert activity.

MS: Is there a greater degree of covert activity now then there was before?

GPS: I don't know.

MS: Are there cultural differences or differences of approach between the C.I.A. and the D.E.A.? Because I know they use some of the same methods and are responsible for some of the same areas. But what are the differences between them?

GPS: I really haven't delved into the respective bureaucracies and how … the C.I.A. has been there longer and it has a broader function.

MS: That was this hypothesis that I was playing with. That Iran/Contra was this national event, this traumatic event, this huge scandal...

GPS: I don't think the D.E.A. had anything to do with it.

MS: But after, following Iran/Contra, the D.E.A. may have given Reagan a way to stay involved in Latin America, in the neighborhood, but with more oversight.

GPS: I don't think that's right.

MS: I saw that your group [the Global Commission on Drug Policy] had this very interesting study where you surveyed all these physicians who ranked alcohol as being far more harmful than marijuana, in this report. I think it was … it's a big bar graph. Yeah, here it is. [Passes report.] So they've got alcohol up here and they've got cannabis as being considerably less harmful, supposedly.

GPS: Good chart. This is part of trying to lay out facts and get people to react to them and start talking about the issue.

MS: But you still feel like marijuana legalization is not such a good thing.

GPS: No, I think it is. But I'd like to see it in an atmosphere of saying the taking of drugs is a problem. And we're looking for an effective way of dealing with it. And the way we've been dealing with it has not worked. So let's try a different way. I think, with all due … I mean cigarettes and alcohol are there, so they're problems. But I don't think they're anywhere near as big a problem as they were when we prohibited alcohol, as when cigarettes were when we had a really effective campaign against taking them. So these things work. And we should start addressing the drug issue in the same way.