Iceland is known for its unique landscape — it can even seem otherworldly.

Drive about a half hour east of Reykjavik, and the ground seethes with steam — a bizarre, thick fog pouring out of the pebbly earth. This is because Iceland sits on top of a geological hot spot that’s pushing up from the Atlantic floor. Just about everywhere you go in Iceland, there’s hot water and steam right beneath your feet. Some of it breaks right through the surface.

And it’s more than just a curiosity. “More or less, all our electricity comes from geothermal,” said Edda Aradóttir. She works for Reykjavik Energy, which runs the Hellisheiði power plant in this part of Iceland. Geothermal steam spins the plant’s generators. It’s the sort of green energy that most of the world wants these days, but it’s not completely clean. The steam contains small amounts of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. Reykjavik Energy wanted to figure out how to keep that carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

“Whatever we can do to make geothermal even greener, we want to work on that,” Aradóttir said. What they figured out was how to lock up that carbon dioxide deep underground, not as a gas that might escape again, but as a mineral bound to the basalt rock below Iceland. In other words, Reykjavik turns air into rock. The process starts by capturing the steam after it’s spun the turbines.

Reykjavik Energy’s Pétur Már Gíslason showed the building where it takes place: “The gas is fed in at the bottom of this tower, and then they put the cold water in at the top,” he said. In other words, the gases get a kind of shower. The result is water filled with dissolved carbon dioxide, like a surging soda stream. Gíslason peered into the building: “You can look through the glass, but I've never been in there because here, you have high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide.”

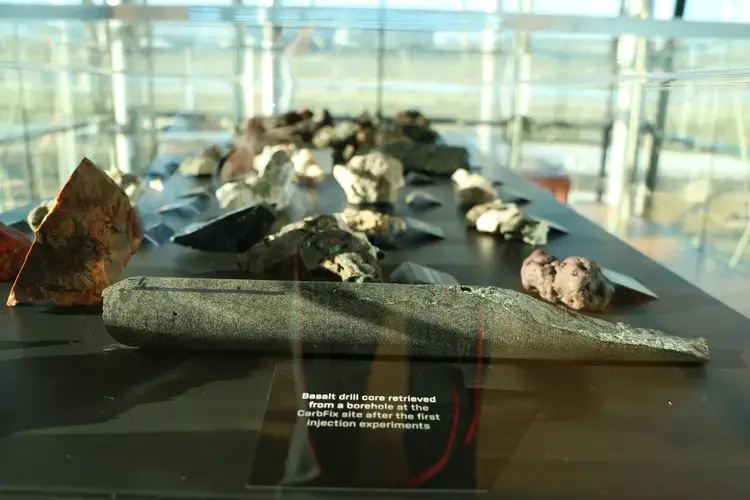

From here, all that soda water gets pumped up to a mile underground where “it reacts with the rock underneath us to produce new types of stones,” Gíslason explained. Reykjavik Energy calls this project CarbFix because the carbon is getting fixed into rock. When it began over a decade ago, the company wasn’t sure how well it would work. But Sandra Snæbjörnsdóttir, the company geologist, says it’s been successful. “We mineralized all of the CO2 that we injected during our pilot phase within two years, or about 95% of it,” she said.

That could make the process attractive way beyond Iceland, in places where electricity comes from burning dirty fossil fuels. There’s basalt all over the world. “It covers most of the oceanic floor, but also 5% of the continents,” said Snæbjörnsdóttir.

“We have enough basalt to deal with all fossil fuel available on Earth. Theoretically, it can solve the problem.”

Aradóttir added, “We have enough basalt to deal with all fossil fuel available on Earth. Theoretically, it can solve the problem.”

Of course, theory is different than reality. There are obstacles to widely adopting something like the CarbFix approach. But the people behind it believe it can help tackle the climate crisis. And while work on refining the process continues, Reykjavik Energy has transformed the Hellisheiði power plant into something of a laboratory for other companies working on what’s called carbon capture and storage.

The CarbFix process captures carbon dioxide from big, single sources like power plants. But there’s already too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. So, another Swiss company called Climeworks is working on the problem from a different angle. Gíslason pointed to a huddle of small buildings he refers to as the "science village."

“They are putting up a system that catches carbon dioxide straight from the air,” Gíslason said. He gestured toward a gray cylinder bolted to the side of the building. “They pull air through this cylinder,” he said. “In here is the filter system.”

Climeworks CEO Jan Wurzbacher explained: “You can imagine the filter as a sponge that captures CO2 from the air. So, in the first step, we flow air through this filter. We heat the filter to around 100 degrees Celsius. And by doing so, the CO2 is released and we extract pure concentrated CO2 from the filter.”

Pulling carbon dioxide straight out of the air efficiently is a big challenge. Even with all the carbon dioxide we’ve been emitting, it’s still just a tiny part of the atmosphere. Climeworks thinks its filtration system is an affordable solution. And they see a big market for the technology in the years ahead, both for reusing some of the carbon dioxide and for storing the rest of it underground.

But first, they’ve had to prove that it works for underground storage. That’s why they’re here in Iceland. “We are combining our method of turning CO2 into rock with their method of capturing CO2 directly from ambient air,” Aradóttir said.

The two companies say they plan to scale up their efforts, but their technologies are still a long way from moving into the mainstream. And some people actually don’t want that to happen. They fear carbon-capture technology could become an excuse for energy companies to keep on burning fossil fuels when we’re already way past the global warming danger point.

But Reykjavik Energy’s Snæbjörnsdóttir says it’s just another tool. “It’s definitely not ‘the solution,’ but it’s one of the solutions that can be used in the fight against climate change. And we will need all the solutions possible for this huge problem to be solved,” she said.