It was a sunny Friday in June when our three-person PBS NewsHour production crew was tagged to go aboard a nuclear-armed submarine on active patrol in the Pacific Ocean. Things didn't go exactly as planned.

Jamie McIntyre, our correspondent, had flown 2,500 miles from Washington, D.C., to Honolulu along with me, the series producer.

To videotape this portion of our news report on the Navy's most deadly ship — an Ohio-class submarine armed with up to 24 Trident D-5 nuclear missiles — we teamed up with an award-winning cameraman, Jay Olivier, who came in from Austin, Texas.

We arrived at Pearl Harbor Naval Base before the sun rose. There at the dock, we filmed men loading the Malama, a 110-foot personnel transfer vessel, with fresh fruits and vegetables, parts and supplies that were going to be delivered to the sub. We would then ride on the Malama to a secret meeting point in the ocean to rendezvous with the warship.

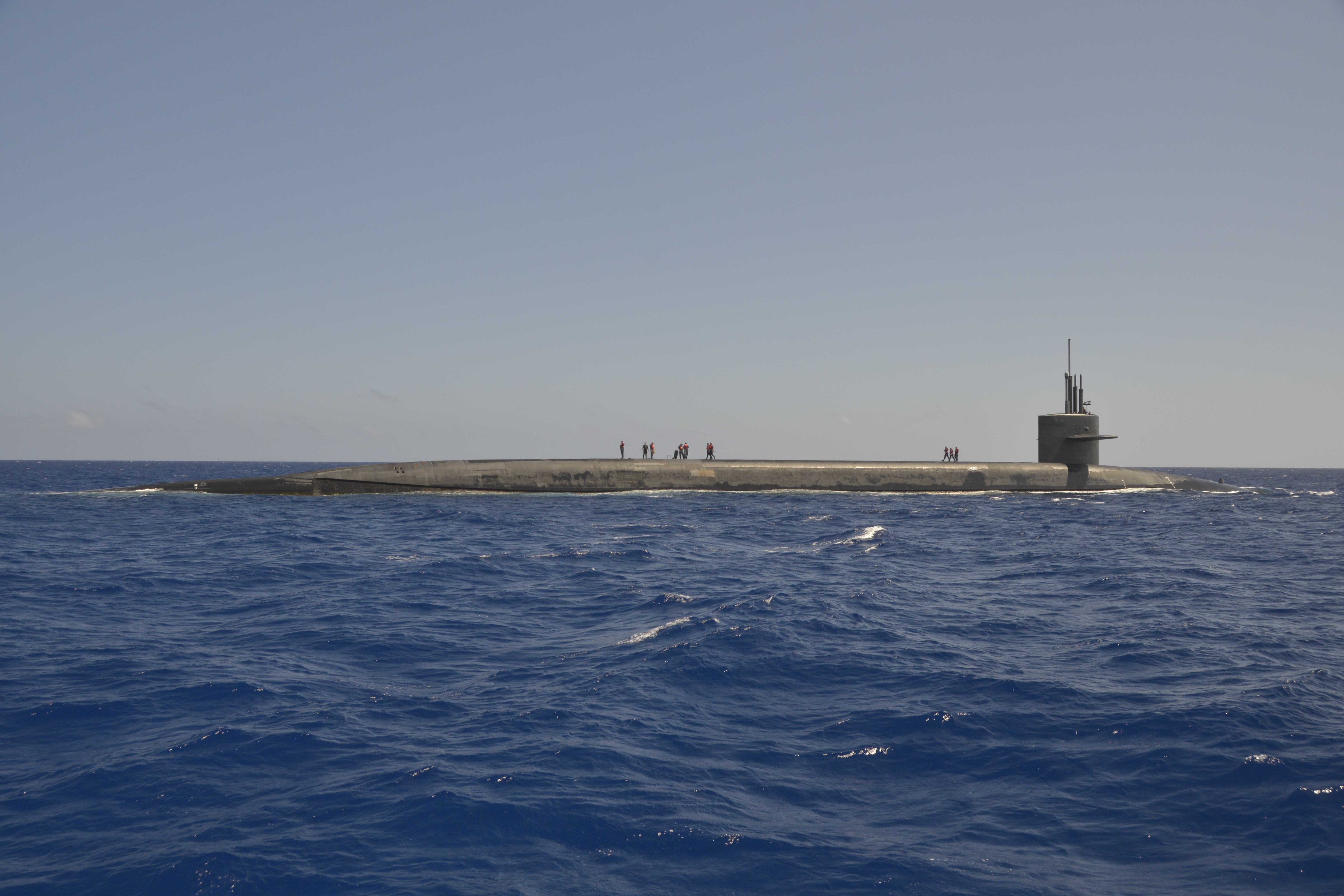

We set sail about an hour later, navigating the open ocean and making a beeline for our meeting point. An hour and a half later, as we eagerly awaited the USS Pennsylvania to emerge from the depths of sea, we finally saw its tall conning tower far off in the distance.

But then the Navy hit a snag that doomed our day on the sub.

Our uniformed public affairs escort told us that due to an operational concern that had arisen — one entirely outside our control — we could not go on board the sub that day. (Because of the highly secretive nature of nuclear-armed submarine operations, we were asked not to reveal any information we learned about why we were not able to board.)

Luckily that turned out to be a hiccup. The Navy gave us a second shot at a rendezvous two days later. Our daylong ride allowed us to shoot up-close video of operations aboard the Pennsylvania, the focus of our story on ballistic-missile submarines which airs Friday.

But our first attempt at boarding the sub on that bright day allowed us to watch a rarely seen resupply of the U.S. warship.

It was a choreography at sea.

First, the submarine cruised toward the transfer ship. Just before reaching the Malama, it slowed while the resupply ship was allowed to approach.

Sailors on the submarine, wearing life jackets and harnesses, emerged from a hatch. Two sailors toward the front and two toward the rear "rolled the cleats," which meant flipping up horn-shaped devices that are used for securing ropes.

Two sailors on the resupply ship threw ropes up, one for each of the cleats, to tie the ships together.

Then the crew on the resupply ship extended a ramp onto the sub, allowing for a few senior sailors to board the resupply ship.

Next came the transfer of supplies. A crane on the Malama lifted huge nylon bags, each about the size of a Smart car. Two were hoisted at a time onto the crest of the submarine. Two sailors then untied the bags from the crane and dragged them toward the hatch, where sailors took boxes of food and supplies out of the bags and passed them down a line of sailors, one to another, and ultimately into the submarine. We watched as nearly a dozen resupply bags were transferred.

Eventually, the men on the sub disconnected the lines that kept the two ships together.

As the distance between us grew, we saw the last sailors enter the sub through the hatches and the Pennsylvania disappear beneath the waves and into the dark water.

Two days later, we set out on our second rendezvous. This time, we were able to go inside and talk to some of the 180 men who travel the world under the sea accompanied by the most deadly weapons in existence.