Cash is virtually worthless, it’s cheaper to cover walls with peso bills than to buy wallpaper, and simple shopping trips turn into expeditions to find the best deals … Photographer Irina Werning captures the chaos.

Irina Werning had to buy new batteries for her camera flash the other day. The Buenos Aires-based photographer first tried her local supermarket, but the price was too high. She went to an office supplies store, a corner shop, a kiosk, a tool shop, another supermarket. This small errand had become an expedition in circumventing spiralling prices in a country whose inflation rates are projected to reach triple figures by next year — among the highest in the world.

“You grow used to it. Since I was born, there’s been inflation, even since before my father was born. It’s such a part of our daily life that it’s inside of us,” Werning says. “I am 46, and for 36 years of my life I’ve had double-digit inflation; on average, that’s 80% inflation every year.”

A simple shopping trip that turns into an hour-long mission to find the best deals is just one of the ways Werning has learned to navigate life in Argentina. The country is experiencing the highest annual inflation in 30 years, accelerated by the Covid‑19 pandemic, shrinking global food supplies, rising energy costs and the economic fallout from Russia’s war on Ukraine. These shockwaves are being felt around the world. In July, inflation in the UK hit double figures for the first time in 40 years, at 10.1%, putting further pressure on families trying to cope with rising costs. On 22 September, the Bank of England warned that Britain’s economy was now in recession, and raised interest rates to 2.25% to tackle the high inflation, but following the government’s mini-budget, financial markets now expect rates to reach up to 6% .

As the rest of the world is forced to cope with soaring price rises, there is no major economy that understands how to manage life with inflation better than Argentina. It’s a reality Argentinians have been living with for much of the last half-century; even today, the country’s central bank keeps printing money to account for the unrelenting fiscal deficit, while owing billions of dollars to the International Monetary Fund.

Werning, who lives in the capital with her husband and two daughters, studied economics before becoming a photographer.

“I thought I would never use my degree, but I came back to Argentina from the UK and use it every day, all the time,” she says.

As Werning witnessed more and more countries hit by sudden inflation this year, she began creating a series of photographs showing how Argentinians have learned to live with financial uncertainty. “The rest of the world is seeing inflation, and I feel that in terms of economic concepts, with 10% or 100% inflation, the results are the same. The mechanisms to protect yourself, the things you have to do in changing your consumer habits, negotiating your salary while it falls in real terms, are all the same,” she says.

She wanted to tell the story of how inflation plays out in real terms, such as stocking up on products when you find better deals, always taking extra cash with you in case you find a good discount, or swapping your car for a bike.

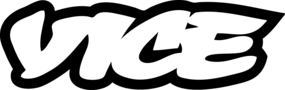

She tells the story through capturing her friends and family and their own struggles with money. “Like the way the English talk about the weather, we talk about inflation every day with strangers, with friends, with family, in the queue at the supermarket. It’s a part of our daily life,” she says.

The photographs are colourful and playful — a way to make economic concepts more accessible — but the sense of inequality and suffering is striking. Four in 10 Argentinians live below the poverty line, and during the pandemic it was estimated that 60% of children were living in poverty. “What is happening is the worst that can happen to a society,” she says, “that the most vulnerable people get more vulnerable, and the richest people get richer. Who wants to live in a society like that?”

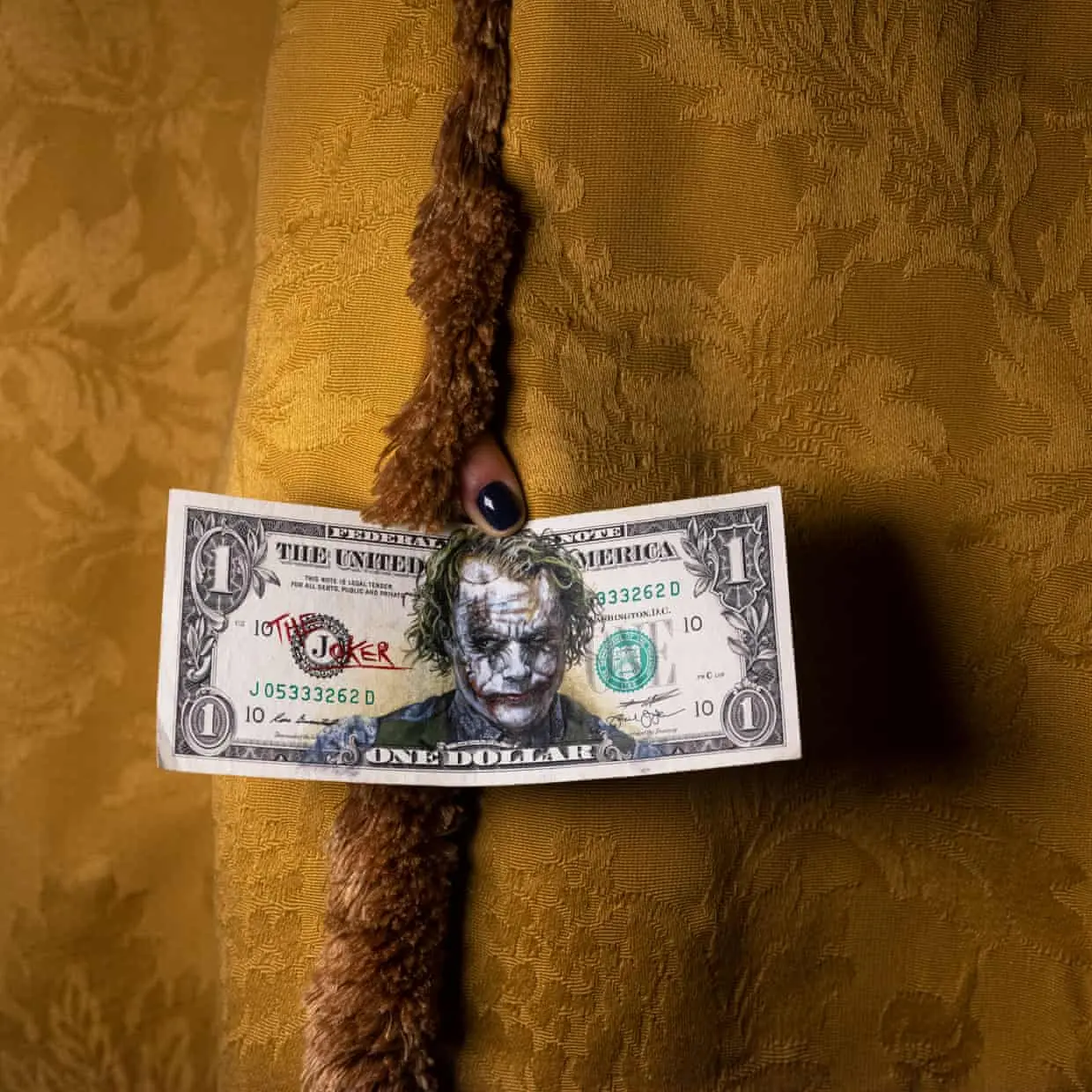

Argentinians have a complicated and unique relationship with money. The country operates almost wholly on physical cash — paper money that has become worthless. There is little trust in the banks and people store their money under their mattresses or in safety deposit boxes. Mostly, they will try to spend their pesos as soon as they get them. “It’s the sensation that the money is burning in your hands,” Werning says. “It’s strange, because you’re poorer in real terms, but you’re trying to spend all the time to protect yourself from inflation.”

To protect their money, many people with higher wages will generally change pesos into US dollars as soon as they get paid, or any currency that’s devaluing less than the peso. Most of these interactions take place on the black market, where around 50% of the country operates. The official exchange rate is147 pesos to $1; Werning says rates on the black market average 290 pesos.

Paper money feels so meaningless that, in one image, Werning’s husband is pasting 10-peso bills to the wall, because the notes are cheaper than buying wallpaper. In another, she photographs a US dollar bill illustrated with the face of Heath Ledger as the Joker by the Argentinian artist Sergio Diaz. Through his work, he seeks to revalue legal tender by converting it into art. “It came from the idea that art saves the world, and in this case art will save us from inflation,” Diaz explains.

Werning also captures Lara, 29, who works in a beauty shop where she acts as the trade union representative. Lara sits naked, showing off her tattoos, wearing a bold headdress with striking makeup framing eyes that stare piercingly into the camera. Her month’s salary of around 140,000 pesos (£880) is stacked in front of her, covering her nipples. The portrait evokes a sense of power — trade unions hold a lot of weight in Argentina as they negotiate salaries twice a year to keep up with price rises. But by presenting Lara naked, Werning is trying to show the vulnerability that all Argentinians feel.

It is a warning for the rest of us, she says. Living with this fiscal precarity leaves people so exposed to forces outside of their control. “This is the way we feel with inflation, we’re vulnerable. And the more vulnerable you are, the worse you’ll have it,” she says.