Recent headlines out of Hong Kong have focused on politics, with the imposition of a controversial new national security law from Beijing. But on the public health front, Hong Kong has been a coronavirus success story, suffering much less infection and death than was expected considering the semi-autonomous city's high population density and proximity to China. Nick Schifrin reports.

Judy Woodruff:

The headlines out of Hong Kong recently have focused on politics. Today, the first resident charged under a new national security law imposed by Beijing appeared in court.

The city was also expected to struggle with the pandemic, which originated in mainland China. But Hong Kong has been a coronavirus success story.

With the support of the Pulitzer Center, and in collaboration with the Global Health Reporting Center, Nick Schifrin has the story.

Nick Schifrin:

George and his son Emilio's winding COVID journey began with slalom in the Italian Alps and dancing through Italy's empty streets.

They had gone on vacation in March and ended up locked down in Italy and separated from his wife, Valeria, back home in Hong Kong, where he's lived for 35 years. They saw each other only on Skype.

George:

Twenty years together, we have never — never had a separation of this kind, of this nature.

Nick Schifrin:

When Italy opened up, they flew back to the Hong Kong Airport in a city that by then knew how to protect itself.

Their 12-hour arrival journey ended with a COVID-19 spit test and a waiting room of socially distanced tables. A positive test, and it's straight to the hospital.

George:

If it comes back negative, you are released, free to go directly to your home, where you will have to do 14 days' quarantine with a bracelet.

It's called stay home safe.

Nick Schifrin:

The mandatory bracelets track everyone's movement and alert police if you go outside.

George:

When we were in lockdown in Italy, we were allowed to go to the supermarket and buy groceries. So we could breathe a little fresh air. Here, we're locked into the apartment.

Nick Schifrin:

One Hong Kong resident was sentenced to three months in prison for leaving home without a good reason.

Can you talk about why you think people in Hong Kong are willing to listen to the government when the government demands steps like that?

George:

Hong Kong is a very peculiar case. We all went through SARS.

Nick Schifrin:

In 2003, the novel coronavirus, known as SARS, hit Hong Kong hard.

George:

The Hong Kong population, myself included and everybody around me, were very frightened, because simply we didn't know what the — what the heck was going on and how bad this thing was going — was going to get.

Nick Schifrin:

SARS killed nearly 800 people here with a fatality rate of nearly 10 percent.

Gabriel Leung:

Two decades of experience have prepared us for this.

Nick Schifrin:

Gabriel Leung is the dean of the medical school at the University of Hong Kong. He recalls how he felt when he heard this year's news of a mysterious outbreak in Wuhan, China.

Gabriel Leung:

The immediate knee-jerk psychological reaction was, of course, flashbacks 17 years.

Ivan Hung:

I think the main difference compared to SARS now is that we are, of course, very much well-prepared.

Nick Schifrin:

This year, the red tape that delayed Hong Kong's SARS response fell away. And Dr. Ivan Hung got swift approval for clinical trials of a potential treatment. And city officials made bulk orders for masks and other protective gear before the city even saw its first COVID-19 case.

By late January, residents were lining up for masks.

Ivan Hung:

People had been queuing for like three or four hours or overnight to buy a box of masks. And the price had gone up like from 100 Hong Kong dollars to $1,000.

Nick Schifrin:

So, the government stepped in and handed out free masks.

Ivan Hung:

Because we learn from the 2003 SARS experience, we have been wearing masks very, very early on in the community. And that is the major difference.

Nick Schifrin:

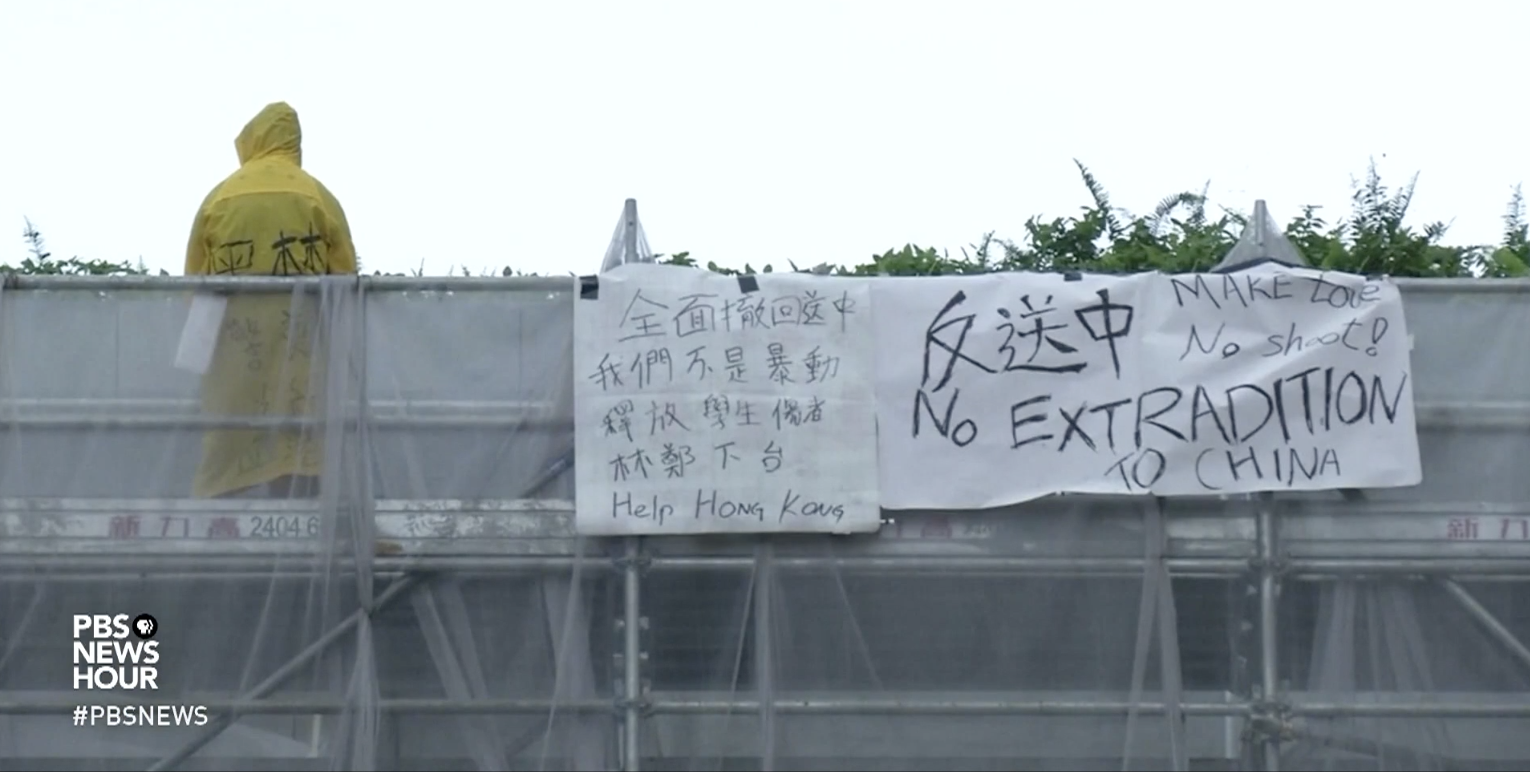

But, by then, the pandemic collided with politics. Hong Kong residents protested a new national security law that restricted their freedom of speech, the city's judicial independence, and threatened to send anyone who calls for Hong Kong independence to jail for life.

Pro-democracy leaders, including Joshua Wong, who had been fighting, disbanded their organizations. In early June, he spoke to a European democracy summit.

Joshua Wong:

Beijing take the advantage during the outbreak of COVID-19, when the world is dealing with the pandemic exported from China to the world, and they suddenly planned to introduce this evil law to Hong Kong, and to silence the voice of the civil society.

George:

The kind of animosity that exists towards the pro-Beijing government is strong. But when it comes to health, and you're talking about someone's family, someone's children, someone's grandparents, people are willing to listen, if they think it's being done for nonpolitical reasons.

Nick Schifrin:

In fact, under political pressure from Beijing, the Hong Kong government at first resisted closing the border with mainland China.

That's when the Hong Kong residents, already mobilized by the massive protest movement, pushed the government to take the threat more seriously. Medical workers launched a strike. Pro-democracy activists created their own COVID Web site. And the scientists emphasized public health over politics.

Dr. Leo Poon is also at the University of Hong Kong.

Leo Poon:

People are extremely aware of the hand hygiene. People are looking for masks all the time. This is not only a small number of people. Actually, the majority Hong Kong people are doing that. Only

Nick Schifrin:

Only four Kong residents have died from COVID. And schoolchildren are heading back to classes gradually, but, even now, there's no resting on their laurels.

Gabriel Leung:

I never like to tempt fate. And my guess is that it's going to get worse before it gets better.

Nick Schifrin:

For George and Emilio, weeks of quarantine required a lot of father-son sports. Emilio perfected his dunks, and George perfected his slow-mo camera work.

And then, right on time, he got the text message he had been waiting for. "Your 14-day compulsory quarantine period will end at midnight today."

And after three months, father and son were free, and finally reunited as a family.

George:

It's absolutely wonderful. Quarantine after quarantine, it got a bit tiresome. I have to say, we're not — no, you're not completely free.

We climbed over a fence to get to a soccer — a soccer pitch. But, immediately, there was somebody who said, sorry, sir, you can't — you can't be here.

Nick Schifrin:

Not completely free, medically or politically, but, so far, Hong Kong has dodged the worst of COVID.

For the "PBS NewsHour," I'm Nick Schifrin.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.