Warning: The following report contains descriptions of sexual violence.

Para ler este relatório em português, clique aqui.

Hospitals and doctors' offices should be safe places, but they were not for the 47 women Setenta e Quatro spoke to. They were subjected to sexual abuse by doctors, nurses, and operational assistants and live with that trauma to this day. How has this happened over the past two decades? What are the failures of the system? Of the Justice? Of the Hospitals?

She had been having unbearable menstrual pain for many months. The best solution was really to go to the doctor. She went to one appointment, then to a second. The doctor's behavior did not arouse any suspicion in her; I would even say that the consultations were trivial. He prescribed medication and the pain stopped. But the success of the treatment required a third visit. Sandra booked it for 2023.

It was scheduled for 4 pm. It was the third time Sandra had been to that private practice in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. She had started a treatment that was having positive results and for the first time the bleeding (and pain) had stopped. Sandra has endometriosis. It is a disease in which the endometrial tissue - the tissue that lines the uterus - grows outside the uterine cavity. It affects one in ten women of childbearing age and causes pain and possible bleeding. "Despite the pain, I was happy that something positive was happening," she says.

She went into the office and the doctor told her to go to "the little room," a specific room for exams. He wasn't supposed to do tests: The appointment was for a discussion about the success of the medication. In that room, the doctor asked Sandra to take off her blouse. She was not wearing a bra.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

She lay down on the couch and the doctor approached. "He brought his hands to my breasts and started groping them," Sandra recounts. "He wasn't supposed to examine my breasts, I hadn't complained at any point." For her, the type of touch was sexual, not clinical. "His gaze never crossed with mine, but I know and felt that something was going on and I wasn't sure what it was about." Sandra froze, or as mental health professionals say, froze. Not knowing where to look, she fixed her attention on the blue walls of the office and stayed that way, static, until the end of those two minutes that "seemed like hours" to her. It was the same blue that she used to draw pictures of doctors' offices as a child; she liked to draw office rooms and doctors seeing patients. It's a detail that she won't forget now.

"Then he asked me if I had [pubic] hair on my vagina." Sandra said no with her head. "He gestured with his hand for me to take off my panties — I had my pants undone — touching my crotch," she explains, uncomfortable. Not knowing how to react, feeling repulsion, she turned to her left side, but the doctor, not realizing or ignoring this sign, continued. He insisted even more.

"He insisted that I take off my pants, because it was necessary to do a pelvic ultrasound on me with an endovaginal probe." The decision to have this examination was made on the spot, Sandra says, since neither the ultrasound machine nor the necessary materials were previously prepared. But Sandra obeyed. She undressed and the next thing she knew the doctor had already inserted the probe, without even wearing gloves. "It was only yesterday that I realized that the machine wasn't even on," she says via video call three weeks ago.

The doctor never looked her in the eye. "He looked at the computer, changed the subject, and the appointment was over," says the woman in her late 30s. What remained from this appointment was a prescription that itemized three packets of the medication she would have to continue taking. She never had access to the report of the supposed examination, nor did it ever appear in her medical file. It is as if it never happened.

Sandra's case was not a "serious breach" of conduct, but, she says, sexual abuse. Generally, a gynecological ultrasound is not a test that is done routinely. "But there are many gynecologists who in private [offices] do the exam in the context of consultation, almost as an objective examination," explains a gynecologist-obstetrician who prefers not to be identified for fear of reprisals.

Sandra has suffered a "hideous malaise" since the day she suffered the abuse. "With each passing day, the disgust I felt for myself was indescribable." It took her a few days before she told her husband what happened: "I was abused." Only after two months of therapy was she able to acknowledge it out loud.

Consecutive baths followed. "I felt so dirty," she admits. Her husband couldn't understand why she was constantly washing herself.

The act allegedly committed by the doctor falls under the crime of sexual coercion, as defined in Article 163 of the Penal Code. Sandra can still file a complaint. She has two months to do so until she reaches the maximum limit allowed by law: six months. She has been advised to do so by her psychologist and her husband, but the fear and shame she feels take up a place that still remains unattainable.

What is hidden when the door closes

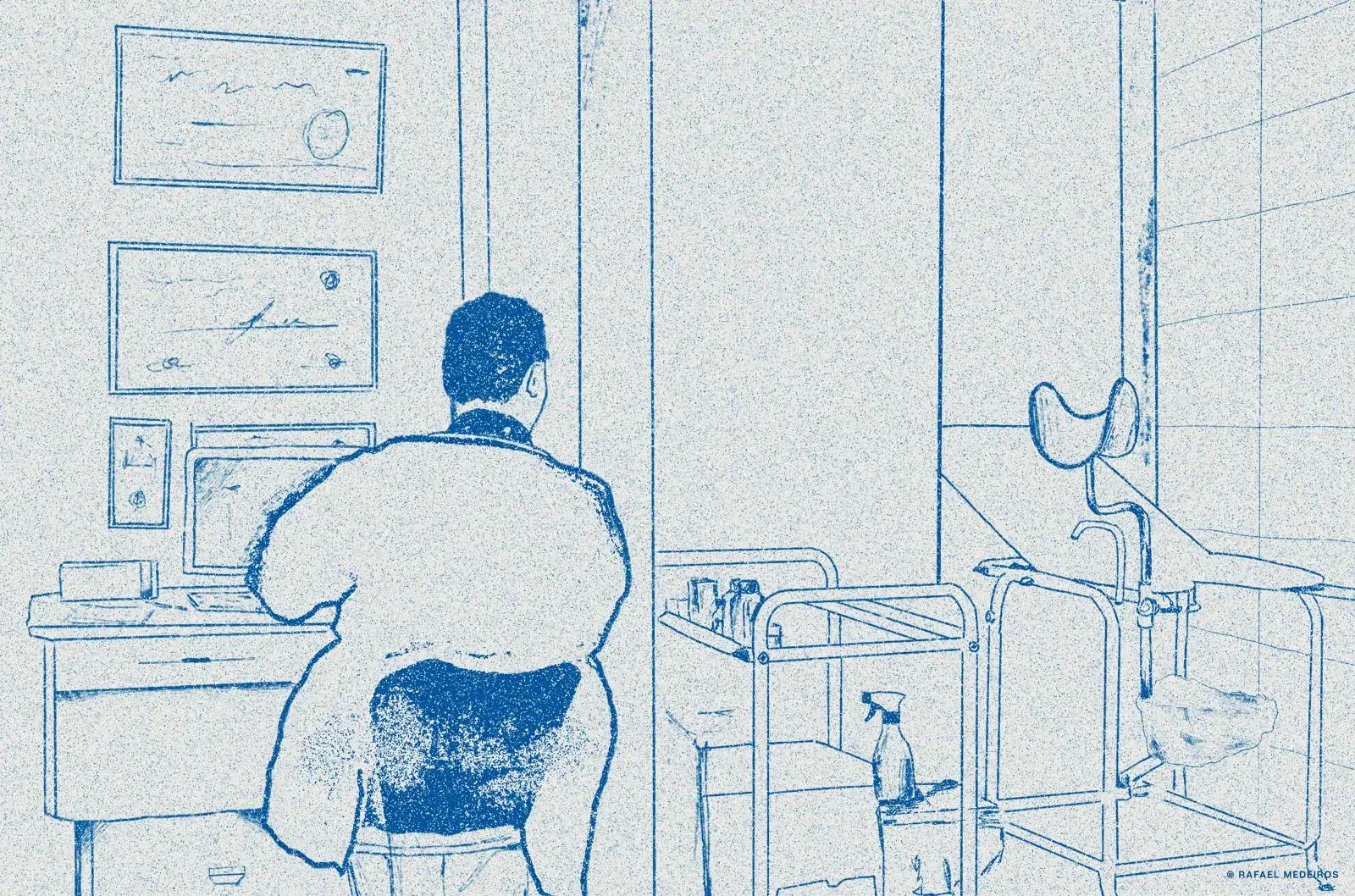

Sexual violence in hospital settings and doctors' offices exists. Although there is little consistent public data on sexual abuse committed by doctors, nurses, and operational assistants, Seventy-Four heard the story of Sandra and 46 other women survivors of sexual abuse (coercion or rape) in hospitals, public and private, and doctor's offices.

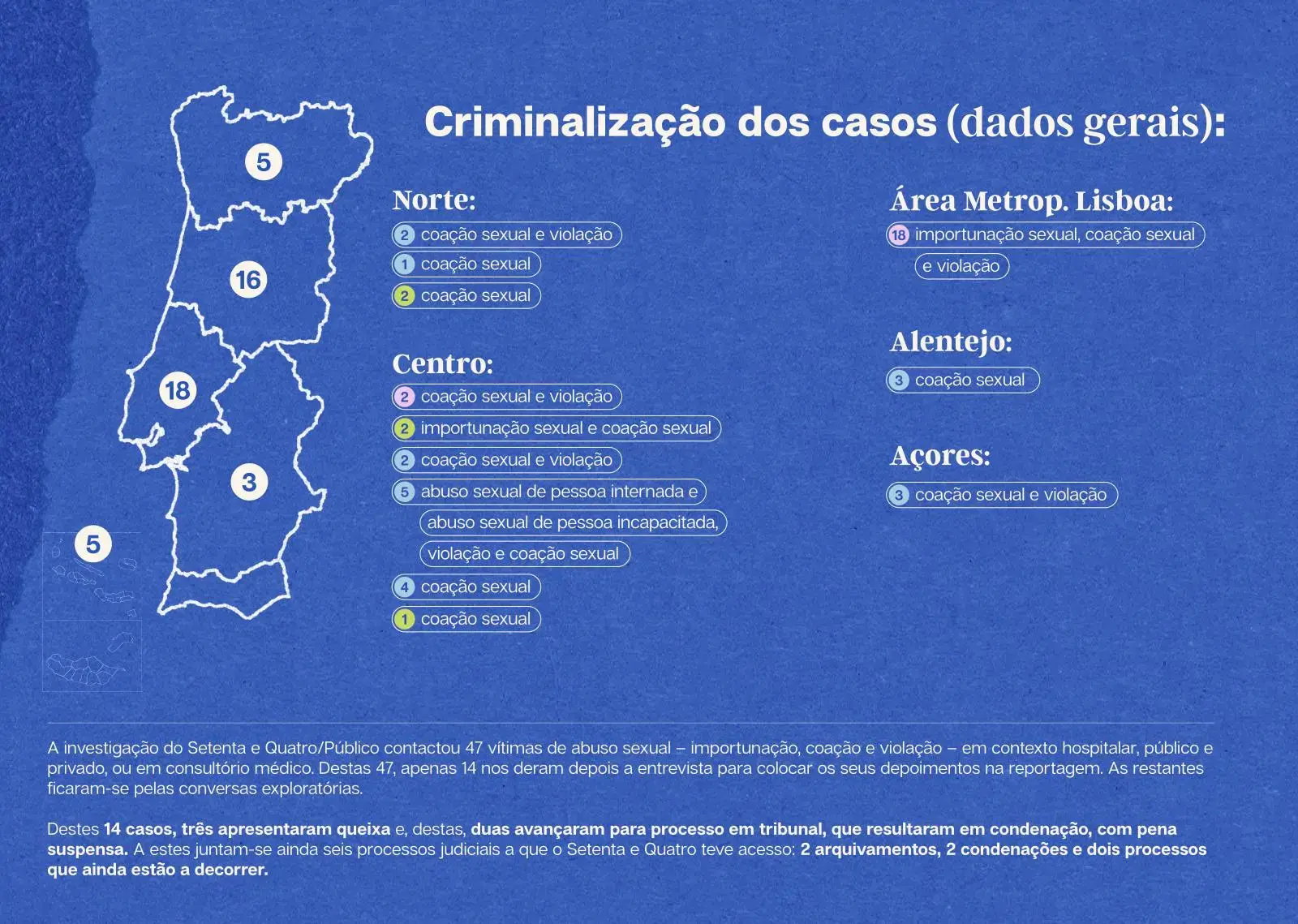

All of these women state that there was never consent. Of the 47 women we heard, who were sexually abused between 2000 and 2023, only 14 gave us permission to use their testimonies in this research, which we will recount in the coming weeks. The remaining 33 stayed with exploratory interviews: the fear and emotional vulnerability they were subjected to in remembering the trauma was enormous. They didn't want to go through it. They did not want to expose themselves, much less denounce their attackers for fear of being discredited. It is also for this reason that the names of the women subjected to these abuses are fictitious, to which we add reasons of privacy and legal protection. The crimes of coercion and rape are semi-public, that is, a complaint by the victim is required, but the authorities and public officials are obliged to report them to the competent authorities.

Over the last 12 months, we've spoken to specialists and legal representatives, doctors, nurses, operational assistants, mental health professionals specializing in Sexual Violence and Post-traumatic Stress, NGOs, researchers, professional associations, unions and leaders of associations to understand how all these women survivors, victims and patients remain unprotected in health services in Portugal. But, above all, how can these abuses to women's sexual freedom and self-determination be fought and prevented?

We analyzed case by case, spoke with people close to the survivors, consulted court cases, read national and international reports, and looked at the few numbers of complaints and claims that exist about this context that has had a significant increase since 2015.

Of the 14 accounts we heard and were allowed to tell, three women filed complaints, but only two went to court, resulting in the conviction with a suspended sentence of a nurse. This was not the only court case to which Seventy-Four had access, but it was the only one in which we were able to speak with all the survivors involved.

The inexistence of protocols for action or prevention of situations of sexual violence between health professionals and patients reveals a "serious negligence" with which the subject is treated by Portuguese health institutions, say various specialists. Complaints do not always reach the competent entities and internal inquiries are not always made.

Besides this, there is no national protocol for prevention and procedures in cases of sexual violence between users and health professionals. The same does not happen with moral and sexual harassment among health professionals: Each Health institution decides internally how to proceed when a health professional sexually violates a user, but by law it must open an internal investigation and report the complaint to the judicial authorities.

The same happens in Justice: from complaint to conviction, the process is very long. And because of this, many victims end up giving up or not coming forward at all — often the lack of material evidence leaves them in judicial limbo. There are no surveillance cameras inside health institutions (they are not allowed by the privacy law), material evidence is often not collected within the legal 72 hours, this is when there are material traces and in case they return to the place where they often suffered the abuse. Not all hospitals have rape kits prepared to collect evidence and this can result in women sometimes having to travel hundreds of miles to other health facilities.

In the case of the archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores, "the reality is much more difficult."

Even so, Teresa Maria Magalhães argues that it all depends much more on the "victim than on Forensic Medicine". "The victim doesn't even need to file a complaint; if she wants to, she goes directly to the hospital's emergency department, and the hospital should call the medico-legal expert. But if there are delays, it's because most of them don't arrive within the window of opportunity that we consider to be the adequate time to safely collect the evidence", reiterates the professor of the Department of Public Health, Forensic and Medical Education at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto. But these traces do not always exist. And these women survivors don't always manage to get there.

Another possibility is to go to a Crisis Care Center, such as the EIR - Emancipation, Equality and Recovery Care Center, coordinated by UMAR, but there are only two in Portugal: in Porto and Lisbon.

Besides all these obstacles, the recognition of the abuse by the victims is a painful process. It involves phenomena of guilt, social stigmatization and even shame. The questions they ask themselves are constant: why they didn't prevent or do something to prevent the abuse becomes a dead end.

"An issue that is given little relevance and that is more or less proven both in other European countries and in Portugal, and this is a similar physical phenomenon: many times the women do not present traces, because they enter in that frozen state, I will use the English expression: the freeze," explained Helena Leitão, Prosecutor of the Republic who finished at the end of May her second term as a member of the Group of Experts on Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GRÉVIO) of the Council of Europe. "They authentically freeze, and that was often used by the opposition, because if there is no trace, it means there is no counter, almost as if it is 'the woman's fault'."

Violence against women is widespread throughout the European Union: "one in three women suffers from sexual violence," reads the directive proposed to the European Commission in March 2022 on combating violence against women and domestic violence.

A study done by the Emancipation, Equality and Recovery Care Center (EIR), coordinated by UMAR and to which Seventy-Four had first-hand access, goes even further: if health professionals, due to their proximity to patients, are in a strategic position to detect risks and identify possible victims of violence, 73.2% of the 325 respondents said they did not feel safe to respond to a request for help from a victim of sexual violence.

Asked whether they had specific training in sexual violence to intervene in such situations, 93.8% of the respondents answered they did not. In addition, 73.2% responded that they did not know about specialized support services for victims of sexual violence, says the study The Challenges in Intervening with Victims of Sexual Violence: A survey of professionals, which will be made public in the coming weeks.

Prescribing a stigma that makes sexual violence invisible

"Who would believe me?" is a question that soon comes up in the cases we heard: all the victims and women survivors we spoke to who did not press charges, citing the status that abusers have and the profession they work in (doctors, nurses, but also operational assistants) as the main reason for giving up. And the few women who did press charges felt at some point in the process that their word would be challenged, because it would always be the word of "a woman against that of a doctor or nurse," or because they considered "something like this unlikely to happen inside a health care institution."

"There are no professions or social statuses immune to sex offenders," reiterates Catarina Barba, a specialist in Sexual Violence and Post-Traumatic Stress to Seventy-Four. There is an urgent need for social and cultural deconstruction: "it's not because a doctor who supposedly 'protects' us, who 'takes care of us', who 'studies hard', stops being a potential sexual aggressor - or any other health professional", she says.

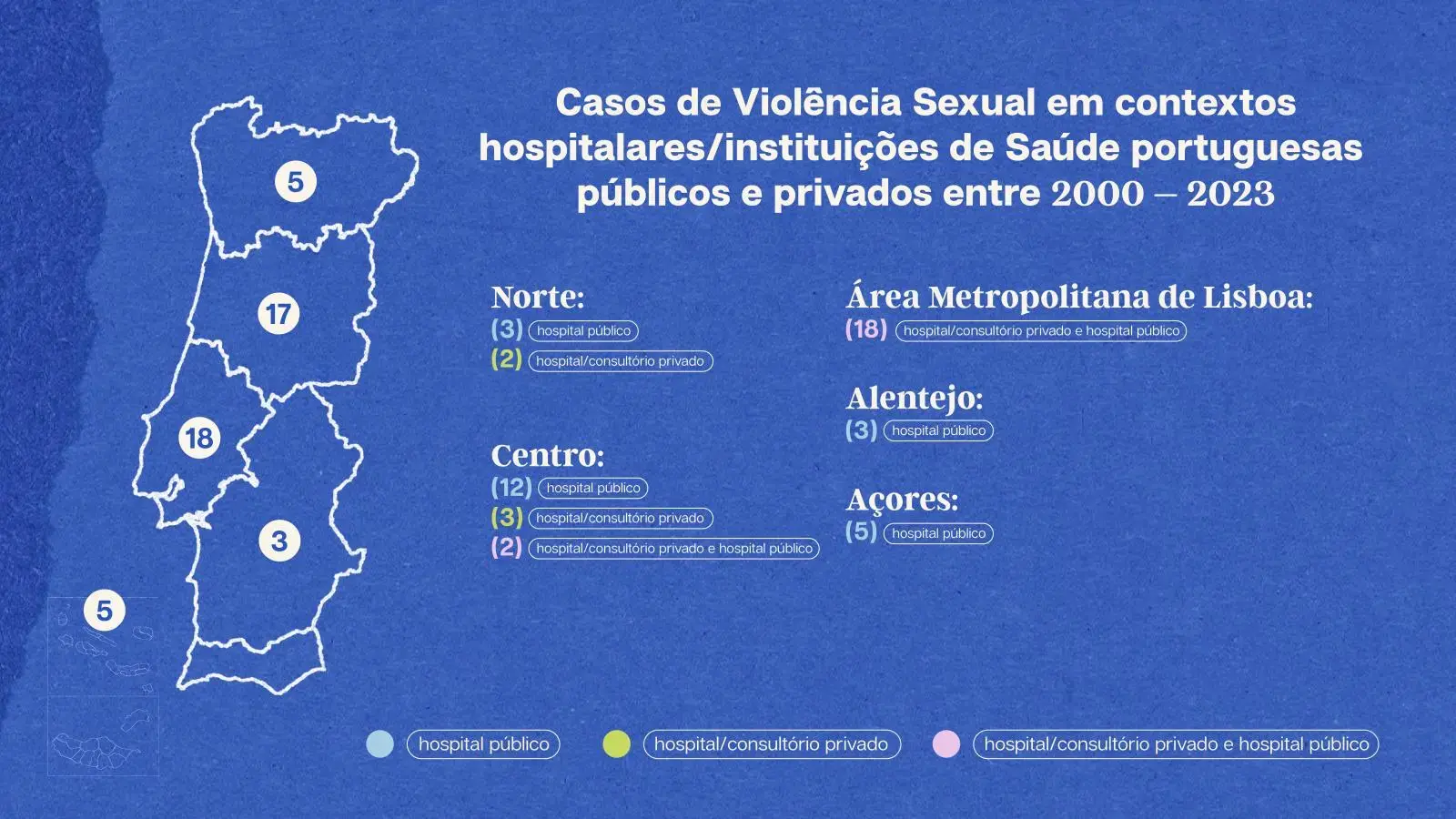

The number of complaints from users reaching the Health Regulatory Authority (ERS) warns of this: complaints about violence, aggression and/or harassment have increased dramatically since 2015. In 2022, the total number of complaints was 149: 28 cases in private hospitals with hospitalization, 15 in private hospitals without hospitalization, 79 in public hospitals with hospitalization, 19 in public hospitals without hospitalization, seven in "social" (nursing homes or long-term/palliative care) and one in "social" without hospitalization.

Less than six months have passed since the year 2023 began and 58 complaints have already been filed, which is 69% of those of the previous year.

This reality was even more nebulous until 2014, when ERS started receiving complaints and claims from users against health professionals. However, the health regulator does not discriminate, because of the privacy law, in its statistics the situations of sexual violence, grouping them under the same heading: "violence, aggression or/and harassment".

In statements to Seventy-Four about what procedure is carried out after receiving a complaint, it replied that, "when it detects evidence of non-compliance and fundamental requirements or procedures for patient safety, it proceeds to a more in-depth evaluation of the situation, through specific diligences with the providers and/or proceeds to the opening of a new process of inquiry, evaluation or even administrative offense.

As far as public hospitals are concerned, the investigation process is the responsibility of the Inspectorate General of Health Activities (IGAS). Setenta e Quatro insisted for several months with IGAS to be able to understand how many of the complaints resulted in the opening of an investigation and, of these, how many in court cases, but we did not get a response until the publication of this investigation.

Over the last month, Seventy-Four tried to find out from the Ministry of Health if it was aware of the complaints, what type of procedures are opened in hospitals, and what measures or regulations existed, but it did not get a response until the publication of this investigation.

If in the last decade the numbers have been growing with the ERS, the same is true both in number of cases and in number of criminal complaints. Let's look at the Annual Homeland Security Report (RASI) of 2022. When it comes to serious violent crime and sexual crime, the report only highlights child sexual abuse (including child pornography) and the crime of rape.

Published in late April, the report indicates that there were 519 recorded cases of rape in 2022 alone. That's a 30.7% increase compared to 2021, when there were 397 cases, a 72% rise since 2015 - there was also a peak in 2019 with 431 cases.

If the cases seem rare at first glance, the director alerts to a reality that is worrying: the survivors, victims of sexual violence, who contact the service center have a very different number compared to those of domestic violence. The center received 153 complaints of sexual violence in 2022, and was only aware of one case in a hospital setting.

"What we have noticed is that because sexual violence is still a very invisibilized violence, women do not seek help from the center. There is a lot of stigma," adds Marisa Fernandes, a psychologist at UMAR's service center and one of the authors of the report on the challenges of intervening with victims of sexual violence. The number of requests for help has indeed increased, but this increase has not been observed in the opening of legal proceedings or even in effective monitoring of survivors, say Marisa Fernandes and Ilda Afonso.

Although 154 countries have passed laws on sexual violence, they do not always apply the internationally implemented standards and recommendations. Portugal is one such case. "The Council of Europe since 2008 has recommended the existence of at least one Crisis Center for every 200,000 women and currently there are two specialized centers for women victims of sexual violence, one in Porto and another in Lisbon," says Marisa Fernandes, with Ilda Afonso corroborating it.

"It is notorious that both in the process of denunciation and in the support to victims there are failures and difficulties in providing answers, especially by the professionals who intervene directly with the victims. It is necessary to review intervention practices, increase the number of specialized care and follow-up responses and train professionals who intervene in the field of sexual violence," warns Ilda Afonso.

If sexual violence in hospital settings is seen as "isolated acts" because of the scant numbers that are publicly revealed, it becomes even more difficult to prove how in these cases a person's trauma can "link the victim to the aggressor." "There may even be 'just' something in the treatment that makes us feel uncomfortable, but we were. Why? Because we need the doctor, we need that consultation, we need that treatment that only 'that' person can define", stresses psychologist Catarina Barba, a specialist in Post Traumatic Stress.

Rui Ferreira Nunes, a psychologist who has worked extensively with people who have suffered sexual abuse, stresses that in clinical terms we know that there is a compulsion to repeat. "A person who has been abused may be abused again in a context that somehow replicates the experience of the first abuse. In a situation where there is a power differential, the person is somewhat at the mercy of the other, since they are usually in a position of vulnerability."

The psychologist's consideration is not at all distant from what Catarina Barba tells us about such acts happening in hospital settings. All these circumstances "discredit a woman: the one who was touched and the one who was raped. And it discredits her, "especially in a hospital setting where other people circulate, where there is the awareness and the feeling that one is not alone and at any moment someone might see or hear," Barba concludes.

A patient’s word against a doctor’s

In her home in the central region of the country, Paula tells how being a mother is a challenging process. Ten years later she realized what had happened to her: "I was sexually abused by a doctor who was 20 years older than me."

"Therapy helped," she begins by saying by video call.

One summer, when she was 20, she decided to take her mother's suggestion and went to her gynecologist and had two appointments. Even then she suspected she might have endometriosis, but she had to wait months for an appointment at the public hospital in her area of residence. Worried, she wanted to be examined as soon as possible, because the menstrual pains were very strong.

The medical office was divided into two parts: the place by the window where the doctor sat with his back to his desk with his computer and some important tools. On the opposite side was a small place reserved by a curtain, around a couch, which clustered on the left side a small island of medical instruments and the ultrasound scanner.

Paula entered, took about five minutes to explain to the doctor what was going on, and he asked her to lie down on the bed to examine her. "I was being watched by him, on the stretcher, and I asked him if it was normal to have pain during [sexual] penetration," Paula says. What followed left Paula not knowing what to do and how to react: "He started penetrating me with his fingers and kept, over and over, trying to give me an orgasm." She didn't have one.

He kept going and she couldn't react, the "shock was so great" that Paula remained inert, completely blocked, without moving. "I just wanted it to be over so I could get up and leave," she admits, anguished. After that, she can't remember if she said anything else to him. But she does remember one detail that haunts her to this day: he wasn't wearing gloves. "I panicked," she says.

This case touches on several issues raised in this investigation. Let's start with gloves. The standard issued in January 2012 by the Directorate-General of Health (DGS) — a joint proposal between the Department of Quality in Health, the Program for Prevention and Control of Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance, and the Medical Association — leaves no room for doubt. "Gloves must be worn when contamination with blood or other organic fluids is anticipated," reads the document. In other words, gloves must be worn when touching mucous substances, because they secrete fluids. Anything of this nature cannot be touched without some kind of protection.

In 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) also recommended it in the Glove Use Information Leaflet. The document reads: "the use of medical gloves is recommended to reduce the risk of health professionals' hands becoming contaminated with blood and other body fluids."

But these are far from being unique cases of doctors not wearing gloves when examining patients. All the reports from women we heard about the specialty in Gynecology reported not having been examined with gloves. And this data is relevant because it shows the predominance of a "sexualization of an act that is clearly premeditated," says Catarina Barba, the psychologist in Sexual Violence and Post Traumatic Stress.

Paula's discomfort grew greater and greater as the doctor approached. She has become so immobilized that her legs are no longer strong. Her voice trembles as she struggles to remember what it took her a year to try to forget. She swallows hard. She knows that after this conversation she will spend a week anxious about having relived everything, but most of all about having verbalized it.

After what happened, Paula began to feel guilt. "Guilt for asking something that somehow could have induced some act." The way she dealt for a decade with this memory — even if repressed in some details — was that "the doctor was showing me something that I was supposed to know and that was not sexual abuse, because the way they represented these moments in the movies was something violent, with a stranger, where a person does not give consent," she adds.

For Marisa Fernandes, this is a "belief" that needs to be deconstructed. The number of rape crimes committed by strangers is lower, as we verified in the RASI, 36.3% of cases in 2022. "Rape and abuse cases are perpetrated less and less by strangers, we need to demystify this belief that the culprit is a man standing there on a corner, ready to attack the victim. When, in fact, the aggressors walk among us. They are people who transmit this confidence and in whom we trust to a certain extent," explains the psychologist.

Unlike Sandra, Paula was not alone. Her mother had accompanied her and was waiting for her in the waiting room. She was also the one who encouraged Paula to talk to Seventy-Four about what had happened to her. "I feel safe doing this for me and for her," Paula says, as she joins her hands with her mother's and adjusts a bracelet.

"As soon as I saw her [leaving the office room], I knew something bad had happened," shares her mother. Her eyes filled with tears as she recalled one of the most traumatic episodes in her daughter's life. "I ran to get her, she was very disoriented. She was limping, she almost fell. When we got in the car, she started rocking back and forth, crying hysterically," she continues in anguish. The mother didn't know what to do. Paula just asked them to leave. She couldn't be there.

Since then she has never been back to a male gynecologist, has never been seen by male doctors, not even in other specialties, and is extremely anxious every time she thinks about going to a hospital, to a doctor's office, or even about having tests done. Paula had her daughter with much fear and caution. The doctor who accompanied her during pregnancy was a long-time friend and all the obstetric exams were done with professionals she knew. Otherwise "I would not have returned to a hospital or a doctor's office."

Taking a denunciation forward is a process that carries several complex stages and, for this reason, many victims end up giving up or not going forward at all. "These are extraordinarily fragile and painful crimes for the victims and for all the actors who have to come into contact with them," explains Helena Leitão, a prosecutor who is finishing her second term as a member of the Council of Europe's Group of Experts on Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (Grévio).

Sandra's and Paula's stories are two of the 47 collected by Seventy-Four against doctors, nurses and operational assistants from hospitals (public and private) and private practices. The vast majority of health professionals (doctors and nurses) have not been removed from their positions, even when there are lawsuits in court.

Paula's mother encouraged her to go ahead with the complaint, but the feelings of guilt and shame weighed heavily again: they gave up because they realized it was a "one-way street." "When I tried to figure out what to do, a lawyer friend said she wouldn't stand a chance." It was the word of Paula, then 20 years old, against that of the doctor, a socially respected professional.

Freelance journalist Cláudia Marques Santos contributed to this report.