When Josephine Kimani needed a form of birth control, she chose the cheapest and easiest solution: emergency contraception. Also known as the morning after pill, emergency contraception has a 95 percent success rate when used infrequently. However, taking the pill frequently could have side effects and has a higher possibility of failure when compared to other non-emergency contraceptives, according to WHO.

"After my mom noticed that I was sexually active, she asked 'Do you use protection?'" said Kimani, a 24-year-old student at the Kenya Institute of Management in Nairobi. "I said not all the time but sometimes I use after pills. She told me the side effects of that and advised me to use the family planning."

Doctors and nurses describe the regular use of emergency contraception as a new fad in Kenya. Girls and young women still need a means of controlling their fertility but do not want to come in to discuss family planning. Kimani now uses an injectable form of birth control, which lasts for three months.

The face of reproductive health is changing in Kenya as efforts increase to educate young people throughout the country and provide access to family planning. Improved reproductive health is important for preventing maternal deaths.

In June 2014, Senator Judith Sijeny pushed a Reproductive Health Bill that created controversy in Kenya. It was incorrectly described in local media as a bill intended to make contraception available for primary and secondary school children.

"Even if you give these kids only contraception and condoms, you shall not have helped them," said Sijeny, who personally encourages abstinence. "That is just a drop in the ocean. You have to protect them, because the complications they are going through because of early sex and pregnancies are much too high."

Before Kimani was a business student in Nairobi, she attended high school at an all-girls boarding school, where she and her classmates were required to take monthly pregnancy tests. Her sexual education was abstinence-only and mostly consisted of videos about STIs and HIV. Kimani recollects that most of her classmates were sexually active anyway.

"I wish in high school, if we were being told the truth about life, that would have been very helpful," said Kimani. "You are maturing, your hormones are growing, there is peer pressure. They don't advise you about contraceptives or anything."

Sijeny's Reproductive Health Bill covers many issues, including in-vitro fertilization, children's health, access to contraception, access to abortion, and sex education in schools.

Family Health Option Kenya (FHOK), an associate member of Planned Parenthood International, is a family planning NGO that has been actively involved in integrating comprehensive sex education into Kenya's primary and secondary schools. Its proposed guidelines are currently undergoing consideration by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development.

In addition to working with groups like the Ministry of Education and UNICEF to institutionalize comprehensive sex education in schools, FHOK has youth centers and outreach programs across Kenya. Esther Muketo, FHOK's Director of Resource Mobilization, says that reaching adolescents is one of their main priorities.

"We need to improve contraceptive access," said Muketo. "Are we going to let our adolescents go ahead with unprotected sex? Because that comes with all the risks. As an organization, we will provide services to young adolescents."

Muketo said that FHOK has faced opposition from community stakeholders, notably the Catholic Church, who believe minors should receive abstinence-only education in schools and have no access to contraception.

Since the Reproductive Health Bill was proposed in June 2014, these stakeholders have voiced their opinions and modifications to the bill are underway, explains Sijeny. Religious groups and parent advocacy groups have insisted that certain parts of the bill be removed, such as a guideline that advises allowing underage girls to ask for an abortion without parental consent. Abortion is illegal in Kenya, unless the mother's life is in danger.

Though Sijeny is taking such opinions into account as she modifies the bill, she stressed the importance of providing women and children with quality health care and information.

"Do you want to tell me we should keep quiet and let our children suffer?" said Sijeny. "Women will keep dying, children will keep dying, the poverty line will not move."

Creating a third space through youth centers

According to research gathered by the World Health Organization between 2000 and 2010, adolescent fertility has remained high in Kenya, with just over 100 births per 1000 women.

"If you don't invest in family planning for the youth, you're in trouble," said Dr. B. B. Kigan, the head of reproductive and maternal services in Kenya's Ministry of Health.

Kenya is committed to international initiatives like Family Planning 2020, which aims to improve contraceptive prevalence throughout the world. Kigan explained that making investments in reproductive health education and youth centers is pertinent to improving family planning.

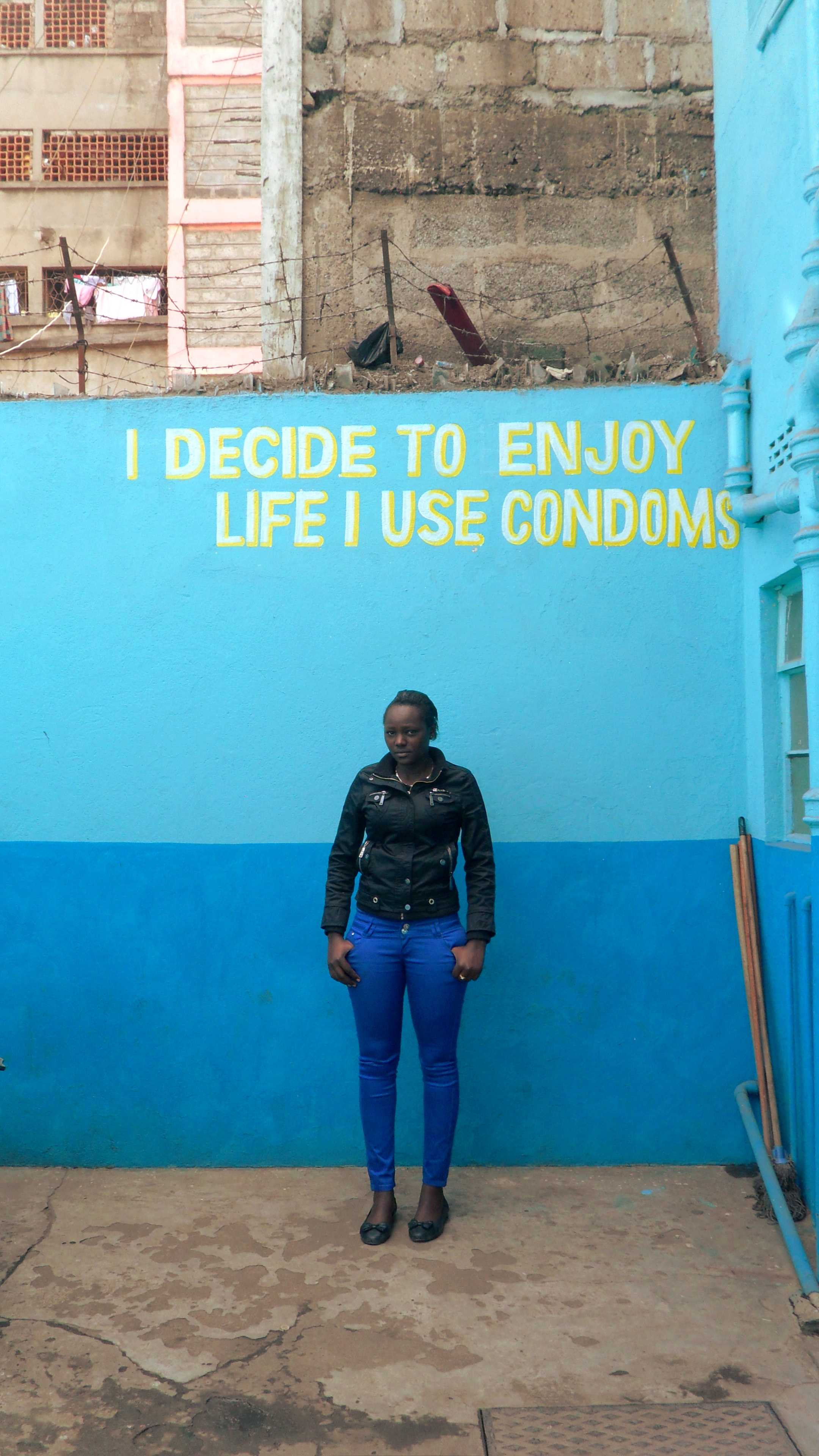

Kimani is a regular member of the FHOK Youth Center in Eastleigh and has mentored young girls about reproductive health. Like other youth centers across the country, the FHOK Youth Center creates a space for young people to spend leisure time and gives them open access to sexual education and a health clinic.

Besides sexual education, the FHOK Youth Center offers technology classes, vocational training, a gym, and a place to watch movies. Initially, Kimani began visiting the center because of the computer training classes. She is now involved with the center's theater group, which integrates acting, music, and dancing to portray issues of sexual reproductive health in Kenya. In August 2014, her theater group won a talent competition at the FHOK Sexual Reproductive Health Youth Festival, which attracts young people from youth centers across the country.

Some youth centers stand alone, while others are situated within hospitals. The Teen Clinic in Busia District Hospital in western Kenya is intended to create the same space as the FHOK Youth Center.

Benson Isatoka, the physician's assistant in charge of the clinic, believes that it is not functioning properly because it does not serve only youth. Rather, it acts as a general reproductive health clinic and accepts people of all ages.

A 21-year old man reported symptoms of syphilis and laughed sheepishly when Isatoka asks how many partners he has. A young woman came in complaining of extensive bleeding—a side effect of her birth control implant.

"So basically the youths that come here are sick youths, not the ones who are happy and free," said Isatoka.

Most of the young patients Isatoka sees are either already pregnant or have sexually transmitted infections. He said the best way to prevent these pregnancies and STIs is to give health education to both youths and parents, because many parents never received sex education themselves.

Bringing contraception to rural communities

Family planning services are often free or inexpensive at government hospitals, though they often run into stock-outs. Private clinics and NGOs try to fill these gaps by providing free or low cost services including counseling and contraception, particularly in rural areas and areas of low income.

"With the government, you won't be able to get what you want, you'll get what they have," said Felistus Kyego, a nurse who works for Marie Stopes Kenya (MSK), a family planning NGO.

In addition to having family planning clinics and social franchises throughout the country, MSK has outreach teams that drive to rural areas to provide women—and sometimes men—with family planning services.

Thirty women slowly filled a room in a health center in Masii, as two nurses held a counseling session in their native language, Kiswahili. One nurse held up diagrams of male and female anatomy. Kyego asked the women if they knew what a copper intrauterine device looks like or where it is inserted. Only a couple of the women could answer correctly.

Kyego has found that women generally dislike the IUCD, referred to as "the coil". Some women are uncomfortable with its place of insertion in the cervix, some believe that their partner will able to feel it during intercourse, and others do not like the idea of a wire inside them.

In the procedure room, Kyego spent several hours inserting implants into the arms of 22 women. Nearly every woman asked for the popular Jadelle implant, which lasts for five years.

The youngest woman who received an implant is 19 years old and was using family planning for the first time. She already had a child, a 5-month-old girl.

When asked why she wanted the implant she said: "I am still studying."