The school's programs present strong evidence that Beijing is exporting its model in a clear departure from its previous, more subtle attempts to peddle influence.

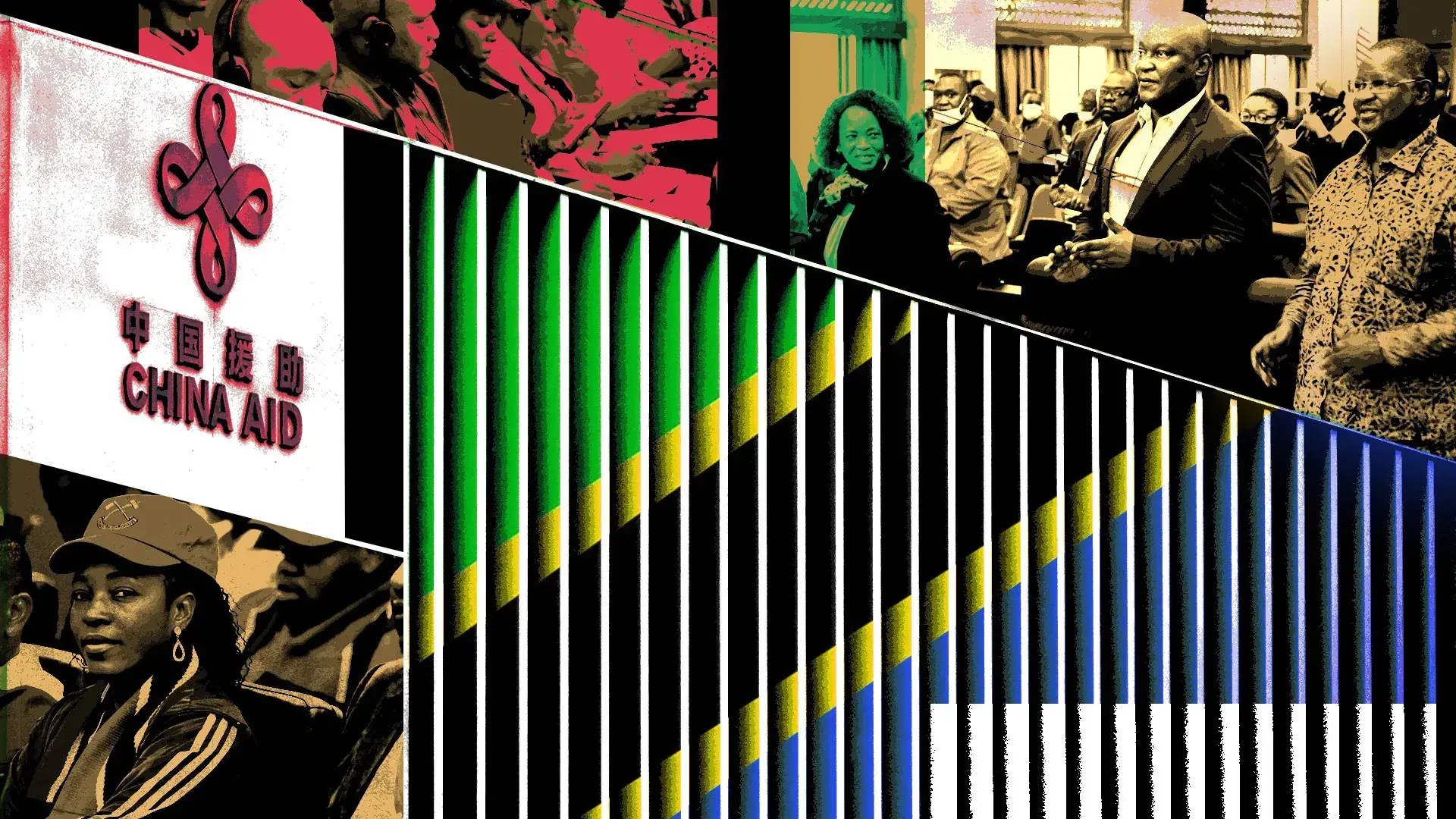

DAR ES SALAAM, Tanzania — The Chinese Communist Party is teaching African leaders its authoritarian alternative to democracy at its first overseas training school—the strongest evidence yet that Beijing is exporting its model of governing in its push to challenge the Western-led world order.

Why it matters: The Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Tanzania is Beijing’s counter to efforts by the U.S. and other Western countries to shape African politics in a fight for influence on a continent rich in raw materials and energy. At the school, the CCP teaches how it fuses the ruling political party and the state, marking a clear departure from Beijing’s previous, more subtle attempts to peddle influence on the international stage.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Cultivating an authoritarian-friendly political bloc could help China reshape global institutions and guarantee markets as Western sanctions seek to isolate certain Chinese industries. Such a bloc would also help the CCP deflect criticism for its human rights record and gain international support for its core interests, such as its territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Chinese and African government officials and Chinese state media have presented the school as a way to promote Africa’s economic and social development, and they’ve cast the CCP’s approach there as a way to alleviate poverty and spur economic development through training effective leaders.

But behind the school’s closed doors, economics takes a back seat to political training. Chinese teachers sent from Beijing train African leaders that the ruling party should sit above the government and the courts and that fierce discipline within the party can ensure adherence to party ideology, Axios and Danish newspaper Politiken learned as the first Western news outlets to visit the school.

Through interviews with African officials who have participated in or observed the training, Axios and Politiken found evidence that the school’s program contradicts CCP officials’ repeated assertion — and many scholars’ views — that Beijing isn’t exporting its authoritarian model for governing.

“There’s been a reluctance from a lot of scholars to say that China is clearly trying to export authoritarianism,” said Daniel Mattingly, an assistant professor of political science at Yale University whose research focuses on authoritarian politics in China. It’s “remarkable,” he said, that there are students who leave the school with the perception that “we need to move to a much stronger one-party state model.”

HOW IT WORKS

Educating ruling parties on cementing their control

The CCP has held an exclusive grip on power for more than 70 years using a model Beijing is now trying to impart to ruling party officials from six African countries who also want to cement their control.

“[T]he most important part of that model is imbuing revolutionary parties with the idea that they are the permanent ruling party and educating them on how to achieve that aim,” Richard McGregor, senior fellow for East Asia at the Lowy Institute in Australia, told Axios.

The school, which opened last year, is a partnership between the CCP and the ruling parties of Tanzania, Mozambique, Namibia, Angola, South Africa and Zimbabwe. All six nations are multiparty democracies, but their governing parties share another key feature: Each has ruled continuously for decades.

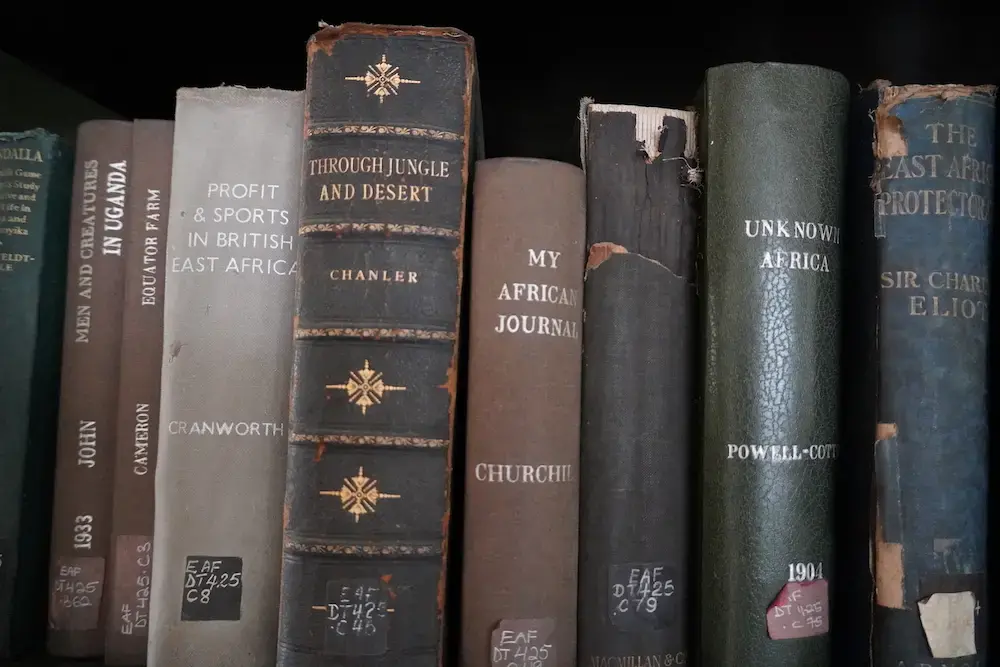

China and these six countries have long had close ties, rooted in their parallel liberation movements. The CCP has for years invited delegations from African nations to attend training sessions in Beijing and in smaller cities around the country. But the scale and scope of the school and its location outside of China — a throwback to Beijing’s Soviet-era strategies — mark a departure from what the CCP has previously done, experts said.

The curriculum indicates the CCP is now “experimenting with exporting aspects of its model,” McGregor said.

Conferences and short course topics at the school are taught by Chinese teachers affiliated with party schools in China. In Tanzania, they teach party governance, party discipline, anti-corruption methods, Xi Jinping Thought, and poverty alleviation. African staff, who operate the school, give lectures and short courses on topics including Pan-Africanism, nationalism and public-sector enterprise management. Together, they share lessons from their revolutionary history.

The school’s offerings are made available to rising young members of the ruling parties — but not to politicians from opposition parties.

“If you are upholding one political party and not offering [support] to the whole political system, you’re offering to strengthen one party within a country, you’re nurturing authoritarianism. That is political interference,” said Anne-Marie Brady, a political scientist at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand who specializes in China’s foreign relations and political influence.

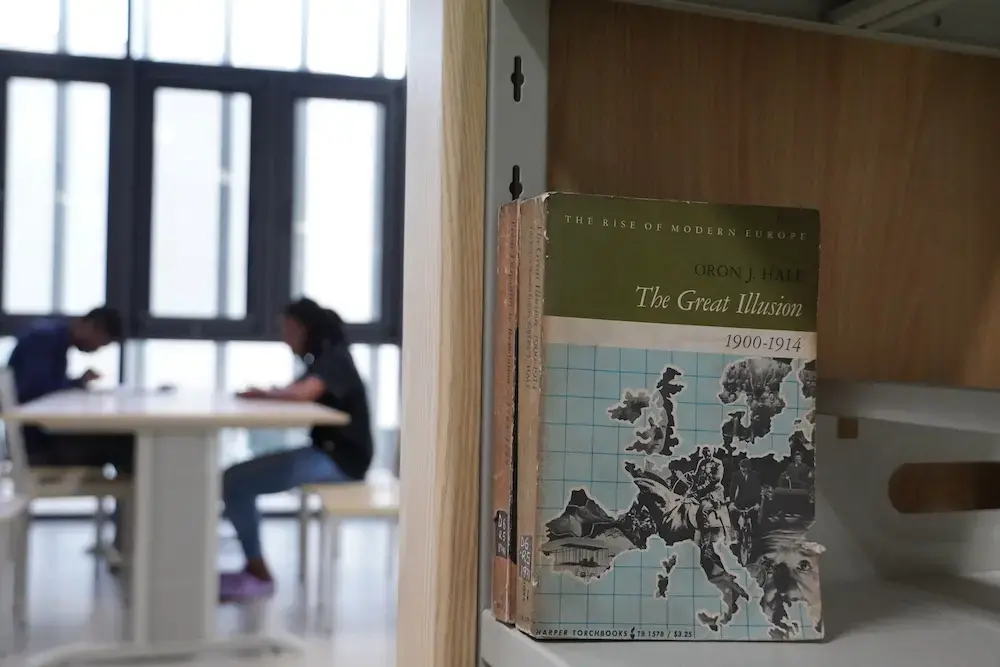

The school, located on a large swath of land 30 miles outside of Dar es Salaam, was funded by a $40 million donation provided by the CCP’s Central Party School, which trains China's top party officials, and built by a Chinese construction company. Its campus is vast, complete with a large banquet hall, gyms, tennis courts and more than 300 hotel-style rooms with Chinese-made furniture. Like many projects in Tanzania, it’s named after Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, Tanzania’s first leader after it gained independence from Britain in the early 1960s. Nyerere is widely revered as the country’s founding father.

The first major training conference, for about 120 participants from all seven parties including the CCP, was held in 2022, and a second major conference with about 170 attendees was held in June this year. There have also been smaller conferences and short courses specifically for members of Tanzania’s ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM).

The Tanzanian principal of the school, Marcellina Mvula Chijoriga, declined to speak to Axios on the record during a visit to the school and declined Axios’ request to observe training sessions and interview staff and participants.

“The [CCP] and political parties in Africa learn from each other on governance experience, and support each other's development path that suits respective national conditions. We don't seek to export our system,” Liu Pengyu, spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., told Axios in a statement. “The [CCP] is the central leading force of all endeavors and causes in China. It is the fundamental reason why the Chinese people and Chinese nation were able to transform their fate in modern times and achieve the great success we see today.”

Tanzania’s CCM did not respond to a request for comment.

WHAT THEY’RE SAYING

“Wonderful lessons”

The African ruling party officials Axios spoke with said they’re enthusiastic about what the CCP is teaching at the school.

Collin Ngujapeua, an official in Namibia’s ruling party SWAPO who attended the June training, said he hoped to implement several “wonderful lessons” taught by an instructor from the CCP’s Central Party School, especially the fusion of party and government.

Though Namibia is a multiparty democracy, SWAPO has governed since the country won independence from South Africa in 1990. In recent years, SWAPO has made moves to grab more power, including pushing through its own appointees to lead the government’s anti-corruption agency.

“Look at the Communist Party of China and the way they are working,” said Ngujapeua, who works as a district coordinator for Namibia’s Okakarara district. “They are working hand in hand [with the government]. … That’s one of the very important aspects that we need also to work on in Namibia and also in other African sister parties.”

During the training, the CCP Central Party School instructor emphasized that party discipline should be above and outside the law, Ngujapeua said.

China’s system features a corresponding party official for important government positions — provincial governor, mayor, university president and others throughout the entire system. The party position is superior to the government position, conveying party directives and guidance, which the corresponding government official then implements.

They are working hand in hand [with the government] . …That’s one of the very important aspects that we need also to work on in Namibia and also in other African sister parties.

Collin Ngujapeua

District coordinator for Namibia’s Okakara District.

That type of system, originally developed by Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin and adopted by the CCP, translates into tighter party control over the state and eliminates checks and balances on the party’s power. In China, the CCP’s discipline commission has sweeping powers to detain, interrogate, investigate and even torture party members.

While all political parties enforce behavior, the Leninist approach to party discipline is different from parties in liberal democratic systems, said McGregor, author of the book “The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers.” “In the case of Chinese officials, the law doesn’t touch them until the party has dealt with them. The law and the courts come after the party.”

[T]he most important part of that model is imbuing revolutionary parties with the idea that they are the permanent ruling party and educating them on how to achieve that aim.

Richard McGregor

Senior Fellow for East Asia at the Lowy Institute

Ngujapeua said it’s “very important” for SWAPO to implement this style of party-state relations at the grassroots level. “We have to work hand in hand, the political party and the government.” The instructor “told us we must solve our own problems. Instead of going to court, instead of using judiciaries, … he said we must solve our own problems internally.”

In a report for SWAPO that Ngujapeua wrote after completing the party training in June and viewed by Axios, he promised to “take out tigers,” “swat [flies]” and “hunt down foxes” in Namibia, using terms the CCP has used to describe Xi’s sweeping anti-corruption crackdown, which he used to both fight graft and take down political rivals, consolidating his power.

Namibia's SWAPO did not provide comment before publication of this story.

This style of party discipline can be appealing to ruling parties in Africa that have corrupt officials and “bad backdoor politics,” Mandira Bagwandeen, a senior research fellow at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, told Axios.

Among some African political parties, “there’s a lot of admiration for the way the CCP is organized,” she said. “It’s perceived to be run like this well-oiled machine that really has its finger on every aspect of economy, governance and society in China.”

In China’s model, African leaders see strong government leadership over a capitalist economic system as a way to break through stagnation, corruption and enduring poverty — and a road to greater global influence in a world still dominated by former colonial powers.

“The China story of rapid economic growth with a one-party state resonates and sounds hopeful to people in a lot of these countries where they have been dealing with the U.S. as the power in the world for decades,” Mattingly said.

ZOOM IN

A fragile democracy at risk

Members of ruling parties may admire China’s model, but Tanzania’s largest opposition party, Chadema, worries it would further weaken the country’s fragile democracy. Tanzania has a multiparty system on paper, but the ruling CCM party has managed to maintain its grip on power for decades — and in recent years, experimented with a more hardline authoritarianism.

China’s governance model would hurt Tanzania, said Reginald Munisi, the director of strategies for Chadema. Opposition party rallies were banned for six years under the previous president, John Magufuli, whose hardline approach demonstrated that Tanzania’s constitution and other legal rights protections weren’t strong enough to prevent the country’s slide away from democracy. In the past five years, several journalists have disappeared or have been detained or murdered. A leading member of Chadema survived an assassination attempt in 2017.

When asked if he is concerned that the CCP may be teaching CCM ways to strengthen its grasp on power, Munisi said, “It’s not just a fear. I think it’s almost an unspoken fact.” Though Munisi didn’t present clear evidence to back this up, he pointed to CCM’s previous crackdown on political rights as an example of how the ruling party is interested in entrenching its power through any means possible.

The CCP's claim that it shares the values of African liberation movements doesn't make sense, Munisi told Axios. “China is market-driven but very strict[ly] controlled when it comes to politics and individual liberty,” he said. “The liberation of an individual cannot just be economic. The liberation of an individual has to be complete: political, economic, and their social beliefs and thoughts.”

The CCP’s promotion of party-state fusion from the centers of power down to local governance can dismantle democracy, Mattingly said. “If you have some of these countries copying what the Chinese Communist Party does at the grassroots — it’s definitely an authoritarian model of how to run a large, decentralized country like Tanzania.”

Lufunyo Hussein, a Tanzanian public servant who leads training sessions at the school, said he believes party-state fusion would be good for Tanzania. Hussein said Chinese teachers at the school give lessons about “how state-party fusion has helped them to reach the level of development they have reached.”

Still, Hussein said, “It's not an approach we just adopt.”

Nyerere founded the country on a policy of non-alignment, meaning Tanzania has long maintained strong relationships with both Western and Eastern countries and that Tanzania’s leaders can pick and choose different pieces of different governance models, blending them into a mixed system, he said.

“If you’re talking about a security agenda, where can I get the best? If you are looking into economic agenda, where can I get the best?” Hussein said. “It’s just a menu, a choice.”

ZOOM OUT

The Chinese model faces challenges

The CCP’s model may be hard to implement in Africa, experts say.

“I think it’s pretty difficult to exert such control the way the CCP does, because a lot of these parties operate in countries that label themselves democracies,” Bagwandeen, the University of Cape Town scholar, said. “It’s difficult, when you have that label, how far you can push the boundaries in the name of political stability, order, and not kind of impede on citizens’ freedoms and rights.”

The CCP is also contending with Western democracies that have been exercising their own soft power on the continent for decades. The United States, Denmark, Germany and other countries have been training political parties across the region for decades, aiming to strengthen multiparty systems and political participation to bolster democracy there.

Party training offered by democratic governments emphasizes leadership transition after elections. Sentell Barnes, the resident program director in Tanzania for the International Republican Institute, a U.S. nonprofit funded by the U.S. government, told Axios that IRI’s party training in Tanzania includes a focus on going from “winning to governing.” This includes capacity-building courses on how to prepare for elections and how to handle peaceful transitions of power after elections — including how to accept an election loss.

Democratic-led training programs also emphasize the importance of press freedom, rule of law and other liberal values. CCP-led training, by contrast, has promoted the benefits of China’s propaganda and censorship regimes.

McGregor added that at “the end of the day, it's a contest of systems.” China now thinks “its system has lessons for the world.”

BETWEEN THE LINES

Beijing’s new export—again

The school’s approach echoes Mao-era policies promoting China as a model to the developing world, but it has key differences.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the CCP supported communist revolutionary movements abroad, seeking to spread its ideology and communist economic policies, including to Tanzania. That support ended after reforms began in 1978. Beijing shifted its focus from party-to-party cooperation toward diplomacy between states.

Now, the CCP is back to exporting a political model — this time, the idea that a single ruling party should dominate the state at every level, but without the ideology-heavy economic policies of the CCP’s earlier decades.

“It’s like back to the Mao era policies again, that China is a model to the developing world,” Brady said. “Except these aren’t revolutionary parties, they are authoritarian parties in power within a nominal democratic system.”

WHAT TO WATCH

The future of China’s model in Africa

It’s unclear if and how far the ruling parties that received the training at the school will go in implementing China’s model.

Beijing’s efforts to create a bloc of like-minded partners for long-term economic benefits and geopolitical influence have already seen dividends: China is the largest trading partner for numerous African nations and receives strong support from across the continent at the United Nations.

“What we see in Tanzania is about building something,” McGregor told Axios. “It’s a new era.”

- View this story on Politiken