Smuggling has been part of the history of this tiny island off the northwestern coast of Haiti since not long after Columbus himself sighted it in 1492 and named it Tortuga, after its appearance from afar: a turtle.

In the centuries that followed, Île de la Tortue was at one time or another a notorious base for buccaneers, a port of call for pirates — whose fictional exploits there have been a staple of Hollywood movies, from “Pirates of the Caribbean” to “Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd” — and a bolt-hole for their booty.

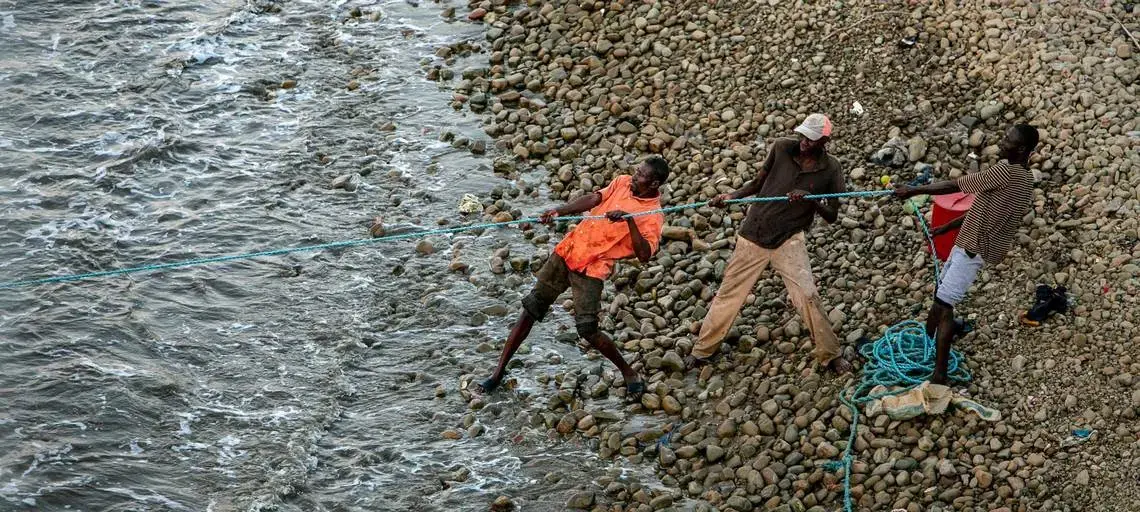

Now, the turtle is once again central to smuggling of a different sort: People. Haitians seeking to escape the continuing cycle of violence, hunger and despair in their homeland come to its rocky seaside villages and coves and pay smugglers dearly for passage on dangerous, overloaded wooden sailboats that depart in the dead of night, attempting to avoid the watchful eyes of U.S. Coast Guard cutters and aircraft that patrol its mangrove-lined coastline.

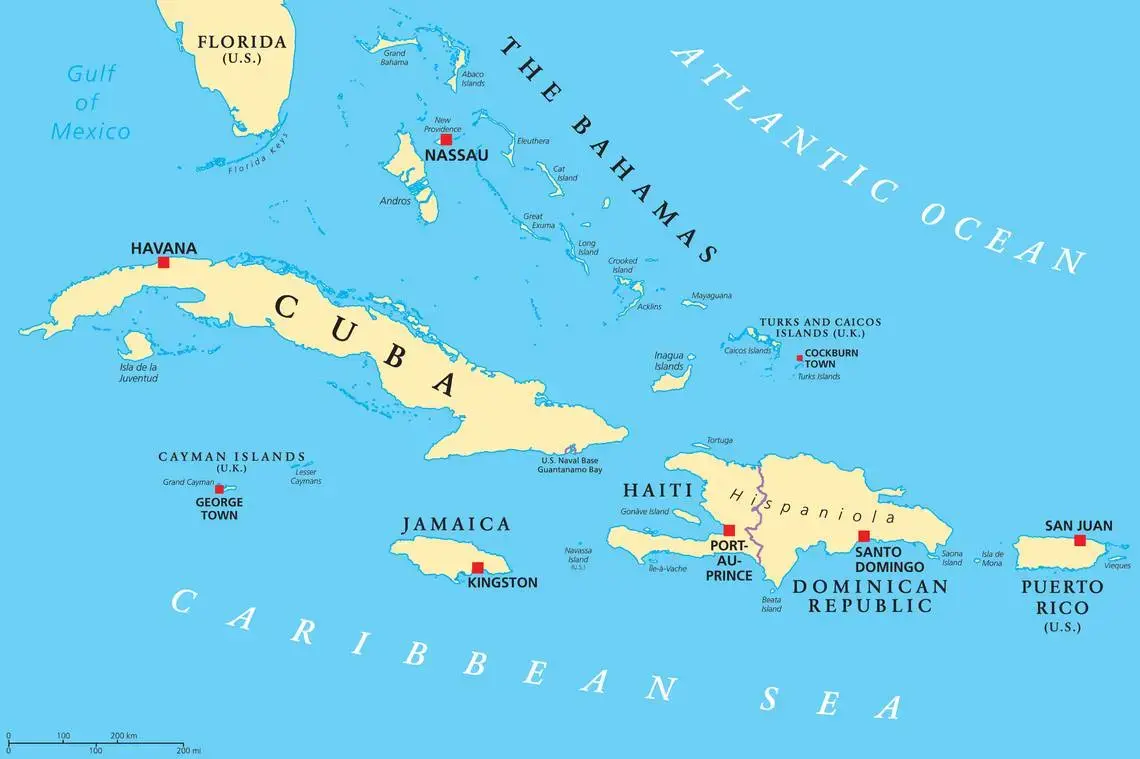

It used to be an almost direct, 600-mile shot northwest across the treacherous waters of the Windward Passage and the Florida Straits to their destination — the southeast coast of Florida — though more often now it’s a more circuitous route with six-foot high seas through the Old Bahama Shipping Channel between the Bahamas and Cuba to reach the Florida Keys.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

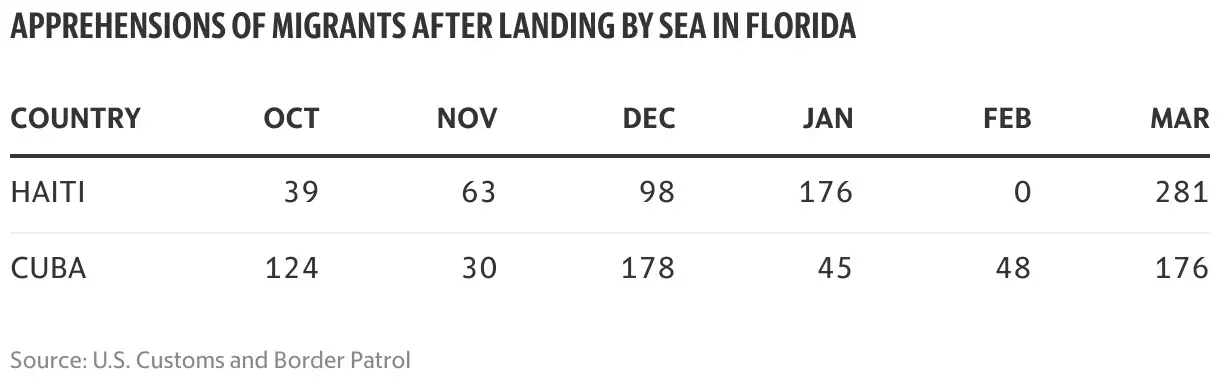

The changing route, along with GPS technology and the use of engines in addition to the hand-sewn sails, have allowed five overloaded Haitian vessels to reach land on the Florida Keys after years of being stopped at sea. The successful landings — two of which were right off the ultra wealthy Ocean Reef Club in north Key Largo — have happened amid the largest maritime migration crisis from Haiti in almost two decades.

In the past eight months Haitians have been leaving from the island and nearby coastal areas on the mainland by the hundreds to reach the Keys — the largest exodus of boat refugees since 2004. Most are stopped at sea and sent back to Haiti. Countless others are lost at sea on what have come to be called “invisible shipwrecks,” incidents involving migrant deaths that go unrecorded because no one knows about them. Still, more than 600 Haitians have successfully made it into the U.S. mainland, where immigration judges will determine their fate.

“Mwen sou voyaj.” “I am on a journey,” said a spirited 25-year-old Haitian man who gave his name only as Peterson, while waiting in La Vallée, one of several villages on Île de la Tortue, to depart. “It’s the biggest risk: Either you die or you succeed.”

The island, 23 miles long and barely four at its widest, is home to 18 rugged seaports, while others can be found along the entire northwest Haiti coast, eight miles away across the narrow channel, Canal de la Tortue. Together, they are spawning a human tide in migration that is once more turning the region’s turquoise waters into springboards for those lacking legal channels to leave.

“In the northwest, they organize a lot of voyages. Some I know about, others I don’t know about,” said a top Haiti National Police commander, speaking on condition of anonymity so he could speak frankly. “It’s like an obsession for the people.”

ESCAPING ANY WAY THEY CAN

Haitians are increasingly fleeing their homeland any way they can. They are landing by the boatloads in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico; in waves in the Turks and Caicos, where the corpses of seven migrants were plucked from the sea in November after their boat capsized; and in the Bahamas. Those with travel visas are jetting across the border to the Dominican Republic, while those without are crossing illegally on foot. Some are hoping to stay. Others hope to make their way to South America and Mexico, and eventually attempt to cross into the U.S. just as thousands of others have tried over the years by traversing a dangerous 7,000 mile route through 11 countries.

The flood of Haitian migrants seeking to cross into the U.S. by land continues to eclipse those who cast their fate on the sea — since October, U.S. immigration authorities have expelled back to Haiti more than 14,100 Haitians who had spent years living in Brazil, Chile and elsewhere in South and Central America before arriving at the U.S. border.

In comparison, the U.S. Coast Guard has stopped more than 5,000 Haitians at sea since October — more than double the number intercepted in the entire previous fiscal year, which runs between Oct. 1 and Sept. 30.

The surge in sea crossings is leading to fears of history repeating itself in yet another massive flow of Haitian refugees crammed aboard overloaded unsafe vessels bound for South Florida.

It happened in the late 1970s, when a famine in northern Haiti led to the first “boat people” appearing in U.S. waters. In the 1980s, the end of the Duvalier family dictatorship brought bloodshed and political uncertainty — and more refugees to Florida shores. In the 1990s, the ouster of the country’s first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, resulted in another tide of refugees. More than 65,000 Haitians attempted to make it through the Florida Straits between 1991 and 1994, 38,000 in just the first six months after the Sept. 29, 1991, coup.

There have been smaller waves, including one in 2004 when simmering political unrest over fraudulent elections resulted in an insurrection and a new flood of boat refugees. Within days, the U.S. Coast Guard intercepted a dozen rickety vessels packed with hundreds of Haitians fleeing the armed revolt and gang violence.

The current exodus is being fueled by destitution and despair, worsening gang violence and kidnappings, soaring inflation and rampant hunger — all exacerbated by last July’s assassination of President Jovenel Moïse.

“Nobody wants to live in a country or a place where you or your kids can be kidnapped anytime,” said Giuseppe Loprete, the Haiti mission chief for the United Nations International Organization for Migration in Port-au-Prince.

The people fleeing hail from all over the country, Loprete said, and cut across Haitian society: “Everybody’s leaving: educated, skilled, unskilled. ... People who could work in whatever economic sector, they’re just leaving.”

The journeys across the water are keeping the U.S. Coast Guard busy. The agency, which has increased patrols in the Florida Straits and near the Haitian coasts, has intercepted an average of four boats a month since October — and nine in just one 24-hour span in mid-April.

“When we encounter these unseaworthy vessels, which are intrinsically unsafe, overloaded with people, and always without basic safety equipment, our primary concern is to remove people from those dangers and to prevent a deadly tragedy,” said Rear Adm. Brendan C. McPherson, commander of the Miami-based Coast Guard Seventh District.

He believes the agency is intercepting most of the boats taking to the sea. But not all.

“My real concern is what happens when the Coast Guard doesn’t know about it, or cannot locate them,” he said. “We see cases where people are lost out to sea and are never found, and that really brings home the message that these ventures are always unsafe and often deadly.”

‘NO WAY I’M GOING TO STAY IN HAITI’

For 26 days Peterson, who like others interviewed in Île de la Tortue for this story declined to give his full name, called the rugged island and its rustic village of La Vallée home. He arrived in early March from Petionville in the capital hoping to get on one of the Florida-bound tall-masted boats often bobbing inconspicuously on the water alongside other hand-built sailboats.

The self-described businessman says he was twice denied a student visa to attend college in the U.S. He had been making a living selling Dominican cosmetics, but said racism in the Dominican Republic, combined with the dangers of gang violence and kidnappings in Port-au-Prince, finally convinced him that it was better to risk dying at sea than from a gang member’s bullet.

Just getting to Île de la Tortue was arduous enough: The road from Port-au-Prince to Port-de-Paix was filled with gaping potholes, and parts of it are controlled by kidnapping gangs. The 150-mile, $14 bus ride took nine hours, Peterson said, and at one point, he ran smack into a shootout between police and gang members.

With just a few changes of clothes, a cellphone and dreams of a better life, he handed a boat captain the equivalent of $5 at a dock in Port-de-Paix and hopped in a wooden canoe to take him across the narrow blue channel to La Vallée.

“I don’t know when I’m departing. All I know is that I am going,” Peterson said. “If the Americans deport me, I am going to turn right back around and take another boat, until I die in the sea. There is no way I’m going to stay in Haiti.”

On April 1, after paying $3,000, he finally got a seat aboard a crowded red and white sailboat and left for South Florida looking forward to celebrating his 26th birthday two days later in a new country.

He didn’t make it. Five days after he set off with a few bottles of Gatorade and crackers, the Coast Guard intercepted his boat in Bahamian waters 18 miles north of Cuba. The Coast Guard said the boat was “grossly overloaded” and taking on water. Peterson disagrees. He says because most of the passengers were from Port-au-Prince and paid for the voyage, the boat wasn’t as crowded as others and “there was enough space for people to sleep.”

Still, some passengers vomited from sea sickness, and others ran out of food. He shared his provisions, he said, with an uncle and two cousins who were also traveling with him.

Peterson and 87 other people aboard, including a baby, were eventually rescued — and returned to Haiti.

His experience at sea, in which he says the sailboat nearly capsized after the mast snapped and the sail ripped, has led to a change of heart.

“I already decided that I am not going to go into something like this again,” Peterson told the Miami Herald after his return to Port-au-Prince on April 10. He complained not just of the dangers of the voyage itself, but of the five days aboard a Coast Guard cutter. “It was a catastrophe. They gave us food without salt, and didn’t let us bathe."

“I am shocked that there are people who say they will try again … and some have already left,” he said. Until a Herald reporter told him otherwise, Peterson believed he had made it into Florida’s waters. That’s what the boat captain, who has since refused to refund passengers their money, told everyone on the boat before their Coast Guard rescue.

When he arrived back home in Port-au-Prince, his face burned by the sun, his mother welcomed him back with tears in her eyes.

“All I can do now is pray and put everything in God’s hands,” he said.

LUSH TREES, UNSPOILED BEACHES AND MISERY

In a severely deforested nation where towns and villages are surrounded by barren mountains, Île de la Tortue stands out for its lush vegetation and the overhanging trees that line the water’s edge and narrow cliffs.

There are few cars and no hotels. Most of its mansions, built by drug lords who used the island as a shipping station for U.S.-bound drugs, are empty or are used to house would-be passengers. The little electricity there is comes from solar lamps, installed by groups in the island’s very active diaspora in South Florida and in the Bahamas, whose southernmost island, Inagua, is just 78 miles from Île de la Tortue.

After the Herald reported on the desperate plight of island residents following a migrant boat tragedy in 2014, the Haitian government promised to kick-start projects and create jobs. But residents say the promises were as empty as the unpaved roads.

Locals travel between coastal fishing villages in small wooden dinghies with wood oars, and either walk or endure back-breaking motorbike rides to get to mountaintop villages.

The island’s mountainous terrain offers stunning views of its unspoiled beaches, crystal blue waters and sand the color of snow.

Residents of Île de la Tortue say that occasionally a few of the 50,000 people who live on the island try to make the voyage to South Florida, but the majority of those fleeing are coming from elsewhere in Haiti.

Haitians, they say, pour in from all over the country after tapping into a flourishing network of middlemen who connect them with boat captains, boat owners and others seeking to make the trip themselves.

The willingness of Haitians to gamble their lives on the ocean has given birth to an underground cash economy in Île de la Tortue and on the mainland. Sailboats, long banned from international cargo commerce, are selling for as much as $25,000. Homeowners are raking in money renting out rooms to those in need of a safe house to wait it out until they can depart.

SOME MIGRANTS PAY, SOME DON’T

Just across from the island on the mainland, in the beachfront neighborhood of Bodin in Port-de-Paix, people like Bernadette Cédieu eke out a living while fishermen try to survive off the overfished waters and children spend their nights looking for eels in the muddy surf.

Two of Cédieu’s eight children, a 25-year-old daughter named “Mama” and a 34-year-old son named Nolaire, took their chances on a two-engine boat headed to Miami out of Bodin in early March. After six days at sea, the overloaded cargo vessel, with 356 people aboard, ran aground on a sandbar 200 yards off the ultra-wealthy Ocean Reef Club at the northern end of Key Largo.

After 158 people threw themselves into the water, U.S. authorities told the remaining 198 Haitians not to jump into the surf. Believing they would be transferred to land, the Haitians stayed aboard. But they were sent back to Haiti.

When Cédieu’s phone rang and she heard Mama’s voice saying she did not make it and was in neighboring Cap-Haïtien on her way back home, Cédieu, 53, said the news sent her screaming into the streets as if she had just experienced a death in the family.

“They arrived and they still deported them. Can you believe that?” Cédieu said, standing on the same bay where her children and the others had departed, the skeletons of wooden boats dotting the shoreline. “Anyway, my children didn’t die. They came back to me, so I have to say God, ‘Thank you.’ ”

Cédieu said her children didn’t actually pay for the Miami-bound voyage. They were allowed to join the trip because “we are all neighbors,” she said, and her son and daughter could help with menial tasks.

Those familiar with how the voyages work say it’s not uncommon for migrants to be allowed free passage in exchange for helping out, or as a favor to the people of the region, who have turned their shores into a way station for those seeking to escape.

Other people can make the journey for free if they can recruit other paying travelers.

Local police say they are aware of the clandestine voyages but can do little to prevent them. They can’t arrest those who are simply waiting in safe houses in Port-de-Paix or Île de la Tortue before making the trips.

But the limitations on the cops can be even more basic: One top police official here told how a judge lacked a car to go to a hotel where police were tipped off that some Haitians were waiting to catch a boat.

Another complication: Local officials who look the other way when they know about upcoming trips — because they themselves have family members making the voyage, several law enforcement officials told the Herald.

“You are fighting against it and you have enemies inside,” said another police official, who also asked for anonymity to speak frankly. “Everyone sees it differently.”

There is no set system on how trips are arranged, police say. Sometimes the lead trafficker is someone who wants to leave Haiti and will work to get a group large enough to raise the money to buy a boat and pay for fuel and a motor. The farther away people live, the more they are likely to pay. One police official told the Herald that the payment can be as high as $4,000 for one seat on a boat — and admitted that sometimes, his own officers are among the passengers.

Sometimes, the trip’s organizer doesn’t actually make the journey, instead paying a captain to take charge and collecting enough money to not only finance the voyage but buy other boats for more trips.

“This is an economic principle: The more people want to leave, the more expensive it gets. The fewer the people who want to go, the more the price falls,” said Principal Police Commissioner Vital-Hernst Caille, who until recently oversaw the northwest region, including Port-de-Paix and Île de la Tortue.

Caille said more-sophisticated organizers raise enough money to buy more than one boat, in anticipation that the trip gets stopped at sea. Given the number of people crowding the vessels, he said, organizers have the potential to rake in as much as $100,000 on a single trip.

Law enforcement sources say that there is never enough food or water on the boats, and most lack a radio or even emergency flares. Also, when passengers change their minds after seeing how dangerous the voyage is, smugglers don’t care. There are no refunds — just an occasional do-over should a boat get stopped.

Neither the police nor the Haitian Coast Guard have access to vessels along the northwest coast because there is nowhere for them to anchor safely. The closest Haitian Coast Guard boat is in Cap-Haïtien, 65 miles away, and because of rough seas and impassable roads, it can take as long as eight hours to respond to a tip about migrants about to set off.

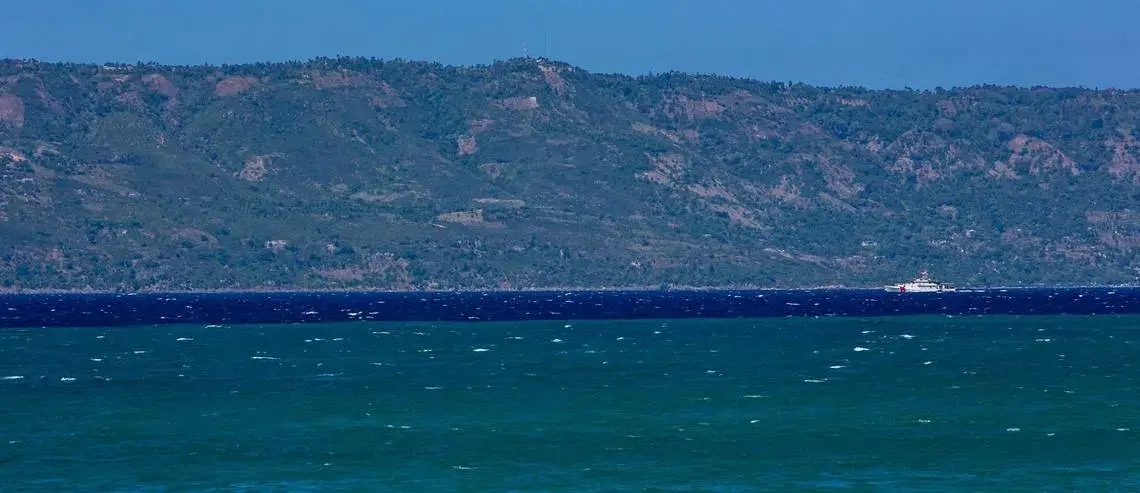

Well aware of Haiti’s inability to patrol its own territorial waters, the U.S. Coast Guard — referred to by locals as Hamithon, as in Alexander Hamilton, the founder of the Coast Guard — has stepped up its presence around Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Bahamas, said McPherson, the Miami-based Coast Guard chief.

Through an agreement with the Haitian government, the U.S. Coast Guard is also patrolling Haiti’s territorial waters. During a visit to the area, a Herald reporter saw a Coast Guard cutter in the distance patrolling the coastline of Île de la Tortue. Soon after, a Coast Guard helicopter flew ahead, followed by an agency airplane.

The way Haitians here see it, the current crisis has been created by the United States’ failed foreign policy in Haiti, and its years of placing its hands on the scales to decide winners and losers in the Caribbean nation’s presidential elections. The U.S. has also promoted trade policies that, in the case of Île de la Tortue, banned its prized wooden boats from U.S. and Bahamian waters, and shown a penchant for sticking with despotic Haitian leaders even when they have not been in the best interest of the people, critics charge.

With every repatriation by a U.S. Coast Guard cutter, the anger and resentment grows, fueling an already hostile climate in the region, where some go as far as to blame the U.S. for their suffering and even the assassination of their president — a charge that the State Department and U.S. federal agencies have denied.

“They say if the Americans are here, and we are in the same Americas and if all of these things are happening and they can help but refuse to, then everyone is going to get on a boat and throw themselves over there,” said Roger Georges, a planter and businessman in La Vallée.

Sagesse-Fils Loriston, a former elected rural official under the municipal mayors, said the U.S. has yet to see a migration crisis coming out of Haiti.

“All of the boats have been sold to do vire won,” he said, employing the Creole expression used to describe the voyages, which means turn around.

EFFECT OF MOÏSE’S DEATH

Before his death, President Moïse made several visits to the northwest, where he and his wife, Martine, once lived. He promised to build an airport to replace the dirt road that planes use to land on in Port-de-Paix, and brought the National Carnival to the city five months before his slaying. He also brought rapper Kanye West and a group of investors to Île de la Tortue, and promised transformation during his final months in office.

His death has left many Haitians in the region feeling robbed, all of it made worse by the relentlessly surging violence.

“How do you want them not to try to leave, to emigrate? Those that used to sail and trade for a living, they’re all sitting down with nothing to do,” said Kindlet Jean-Baptiste, 36, a teacher who lives on Île de la Tortue. “They have to try and get out.”

Everyone, he said, is well aware of the risks of the sea voyages. He ticks off the possible outcomes:

“If I go and the government doesn’t catch me, and I arrive, I’m lucky, good, I’m saved. Two: I’m on the boat and I never make it to shore, I die. Three: I leave, I don’t make it, I don’t die, and they take me back where I started,” he said.

“I can sincerely tell you, life is not really good for us,” said Jean-Baptiste. “Misery is spreading, insecurity is spreading, so it’s impossible not to want to go. … There are some families who go two, four, five days without eating.”

Jean-Baptiste said he often goes without pay because parents can’t afford the $20 annual school fee. No salary means no money for food.

He tries his best to sound convincing that he won’t try to take a boat to Miami.

“I have a family. I have two children here. But if one of my children asks me for a piece of bread, I cannot extend my hand and give it to them,” he said. “For me, I exist. I am not living.”