Almost three years have passed since a much-vaunted peace deal brought an end to the longest-running conflict in the western hemisphere. Try telling that to the people of Tumaco, where the murder rate is four times Colombia’s national average and violent clashes have displaced at least 2,700 people already in 2019.

Many in Tumaco had high hopes of the accord signed between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, in 2016. Encompassing a small Pacific port city and a sliver of southeastern Colombia near the Ecuadorian border, the municipality saw some of the worst of the country’s 52-year armed conflict.

For decades it was controlled by the FARC, who terrorised Tumacoans and converted the largely rural region into one of their most important cocaine-producing centres. When the guerrilla movement demobilised in 2017, Tumacoans thought they had been freed from the rule of a brutal and illegal armed group.

But Tumacoans say they now feel robbed of their chance for peace. The FARC might be gone, but other illegal armed groups are taking their place – groups referred to as “the dissidents” – and the thousands displaced are getting little humanitarian assistance.

The dissidents are responsible for the worst levels of violence in Tumaco since 2014, two years before the peace deal was signed, and their proliferation is both an indication and a consequence of the flawed demobilisation process the FARC is going through in the region.

Unlike the FARC, the dissidents have no political ideology. Their sole purpose is gaining control of Colombia’s hugely profitable drug trade. As the country’s number one producer of coca, the base for cocaine, Tumaco is the country’s number one magnet for dissidents.

The government has deployed around 9,000 military personnel to Tumaco in an effort to combat illegal armed groups. But the lack of presence of other state institutions, like courts and prosecution offices, has allowed the armed groups to exert control over the population.

Colombia’s constitutional court has described their growing presence in the region as a “humanitarian crisis”, and a Human Rights Watch report in December said that “nowhere else in Colombia is sexual violence by armed groups so widespread”.

Although they are technically new, in essence they differ little from the FARC as their members once belonged to the now-defunct guerrilla group. They either rejected or grew disillusioned with the peace deal and picked up arms once again.

The dissidents have been increasing in number and are targeting old comrades who have so far adhered to the peace deal, hoping to turn them back to guns, drug-trafficking, and violence.

In addition, Tumaco’s so-called “transition zone” – where demobilised FARC combatants live in army-protected areas to be trained and supposedly reintegrate back into society – may soon be dismantled. The fear is this could drive more ex-FARC members to join the dissident ranks, sometimes just to avoid being killed.

The disappeared

At least 63 Tumacoans were declared victims of forced disappearance in 2018, on a par with the year before but 70 percent up on 2016. Human Rights Watch says the real numbers are probably much higher as most Tumacoans are too scared of the dissidents and too distrustful of the authorities to report violence.

Take Andrea Garzon. She never reported her brother’s disappearance, which happened on 16 November, 2018. She and her parents began to search for him after he didn’t come home as usual from his work shift. Worried he might have run into one of the armed groups that roam their small town in Tumaco, they searched for him well into the night, to no avail.

Early next morning an unknown man showed up at their doorstep. “Don’t look for him anymore,” Garzon, whose name has been changed for security purposes, remembers the man saying. “Otherwise you will all end up dead.”

The Garzons were so scared that they mourned in hiding, crying only inside their own home.

“We don’t even dance or sing anymore.”

With no one to turn to, Tumacoans live in fear. Garzon says the only ones celebrating anything are the armed groups. “We don’t even dance or sing anymore,” she says.

Garzon does not know exactly who “disappeared” her brother, but she is sure whoever it was belongs to a dissident group.

Nationwide, an estimated 2,000 former FARC combatants have joined the ranks of the dissidents, and military intelligence points to the presence of at least three distinct dissident groups operating in Tumaco.

A flawed demobilisation

According to sources close to the demobilisation efforts – who spoke to The New Humanitarian on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of these issues – the national FARC secretariat bears at least part of the blame for the failure of the process in Tumaco. In particular, they blame the FARC leadership for choosing one of the group’s most visible national commanders, known as Romaña, to initially lead the transition zone here.

Unlike most of the FARC men and women in Tumaco – most of whom are either indigenous or black – Romaña is white, had rarely set foot in the region, and is described by former comrades as uninspiring and despotic.

Rodrigo Angulo, a former member of the FARC’s old militia branch in urban Tumaco, says Romaña and his men “discriminated against us because we were black and because we were urban”. Some mid-level commanders who didn’t get along with Romaña quickly left the demobilisation process along with their followers and formed dissident groups.

But there’s plenty of blame to go round, especially for the failure to reintegrate the former combatants and address their needs as they struggle to build new lives.

For one, Tumaco’s transition zone lacks potable water. A nurse visits only a few times a month, not nearly enough to meet everyone’s medical needs, says Fabio Hernando Areyano, alias Peter, the current leader of the zone. “I have yet to see the first prosthesis for our wounded men,” he adds.

The former FARC fighters in this transition zone – one of 24 across the country – have tried to make a living by launching agricultural projects, like pineapple and aloe vera plantations. But they lack the money and training to keep the projects alive.

“We want to work, but we need help to generate employment,” says Peter. “We need training here so that we don’t have to return to coca or the jungle,” he adds – meaning the guerrilla war when he says jungle.

People here are scared of what might come in August, when the lease for Tumaco’s transition zone ends. It’s not clear yet whether the government and the FARC will renew it. If they don’t, the demobilised FARC members in Tumaco will not only lose their homes for the past two years but also the protection soldiers grant them from the dissident groups.

Now unarmed, the former FARC combatants fear that without protection they will be targeted and killed by the dissidents. “The moment these soldiers go away, I’ll jump into the vehicle with them,” says Peter.

Without proper training and reintegration to allow them other opportunities, many might go back to doing the only thing they know how to do: war.

Ignoring the displaced

Tumaco’s dissident groups are engaged in a deadly battle against each other for control of the drug-trafficking routes the FARC left behind. Confrontations between them have forced more than 2,700 people from their homes in the Tumaco municipality this year alone.

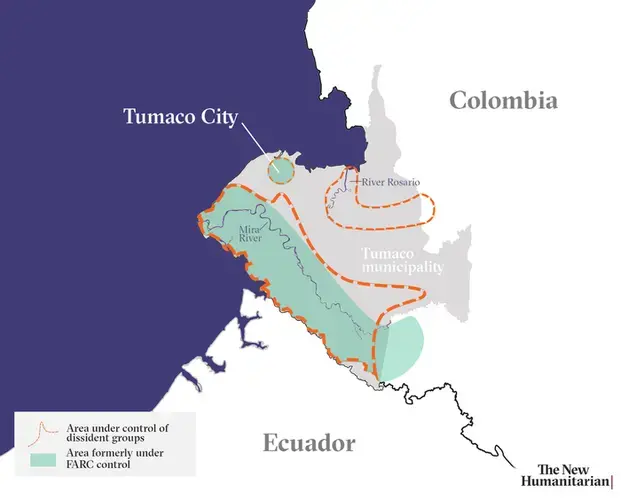

The largest single displacement took place on 16 January, when at least 785 people fled their homes close to the Mira and Rosario rivers and sought refuge in Tumaco city. These rivers’ banks are dotted with coca plantations and cocaine laboratories, and their waters are a major route through which cocaine exits Colombia.

Colombian law obliges local authorities to provide displaced people with humanitarian assistance and register them with the Unit for the Assistance and Reparation of Victims, or UARIV, which is responsible for their long-term needs.

But Tumaco’s mayor’s office is accused of failing to fulfill its obligations to the displaced, often placing them in an overcrowded football stadium where they have to sleep on the floor. Humanitarian aid is often late to arrive, if it comes at all.

“Authorities in Tumaco have failed to provide adequate assistance to victims of displacement as they flee their homes,” says Jose Miguel Vivanco, director of the Americas division at Human Rights Watch.

With no place to stay, displaced people seek the hospitality of acquaintances or family members who moved to Tumaco city years ago. Their homes are usually wooden shacks on puny stilts that spill out into the sea.

“In a 10x10 (-metre) home, we usually find up to five families sleeping on the floor,” says a humanitarian worker in Tumaco who preferred not to give their name. These homes have no sewage, running water, or electricity. And those displaced from the countryside struggle to find work in a city with 74 percent unemployment.

The same groups that displaced them from rural Tumaco have urban militias in Tumaco city. They threaten anyone who talks openly about the reasons for their displacement. Rape and other types of aggression are common among Tumaco’s displaced population.

Edilberto Clevel, one of the victims of the mass displacement that took place on 16 January, says the mayor’s office treats displaced people like a hot potato. “It’s a mess,” he says. “The mayor is in prison, the mayor in charge says we are not his responsibility, and those who he says are in charge say they have no resources to help us.”

“They would rather be shot than starve to death in Tumaco.”

The authorities are unable to produce a census of the displaced and collect information in a timely fashion. This in turn delays humanitarian assistance.

International aid agencies are only meant to respond when the authorities have gathered the data and asked for their help. So NGOs are having to skip protocol, delivering food and medicines to those they deem are most in need.

“We see a week, two weeks go by, and the situation is not made clear,” says one NGO worker, who requests anonymity because he fears the authorities might retaliate by ending their collaboration with his organisation. “So we have to prioritise the [displaced] population’s health and care for them, at least healthwise.”

Given that people often find themselves worse off in Tumaco city than in the rural region they fled, it is no surprise many choose to go back, despite the violence. “They would rather be shot than starve to death in Tumaco,” explains the NGO worker.

Clevel has to shuttle back and forth between his home in the Rosario river region and Tumaco city as sporadic clashes between the armed group erupt and subside. He is used to never feeling safe, and the strain is apparent.

“There’s a limit to how much hunger a person can bear,” he says. “Rio Rosario is going through every ugly moment that ever existed. The armed groups have bombs, grenades, visors, [armoured] vests, everything,” he adds, noting they are as well-equipped as the army.

A conflict recycled

Accurate figures are hard to come by, but women in Tumaco are believed to endure the highest rate of sexual violence of any municipality in Colombia.

At least 74 women reported being raped or sexually assaulted in 2017 and 2018, but Human Rights Watch says the real number of cases could be a lot higher as most victims in places like Tumaco never report it.

For example, 28-year-old Luisa Ochoa never told the authorities about the several times she has been raped. The last time she was assaulted, in 2017, two armed men grabbed her from behind as she stood outside a nightclub. They put her into a taxi and took her to a remote house that she believes was located somewhere in the outskirts of Tumaco city. She doesn’t know exactly where, as she was blindfolded on the way there.

“They tied me to a bed, took my clothes off, and abused me during eight days,” says Ochoa, whose real name has been changed for security reasons. She never knew who her captors were – they always wore balaclavas – but she is positive they were part of the illegal armed groups who control Tumaco city.

When they were done with her, they left her, weakened and distraught, in the same place where they found her. She spent several days in a hospital, where she found out she was pregnant. She chose not to have the baby.

“It is nothing short of a miracle if a woman (victim of sexual violence) ever receives the aid.”

By law, the Colombian state is supposed to grant victims of sexual violence with temporary housing, transportation, and even food. But Ochoa never received any such assistance.

“It is nothing short of a miracle if a woman (victim of sexual violence) ever receives the aid,” says Vivanco, of Human Rights Watch. Ochoa tried to kill herself with poison after she was kidnapped. Although they are required to, the authorities never provided her with psychological help. But she got lucky. Another victim of sexual violence took her to Médecins Sans Frontières, where a psychiatrist gave her a new will to live.

Despite the large military presence in Tumaco, the region’s violence is getting further out of control with each passing month.

While thousands of soldiers patrol the only road that connects to Tumaco with the rest of the country, the dissidents are cutting through the jungle to create new trails through which they can transport coca.

Aside from the armed forces, there is no state presence in Tumaco. There are few prosecutors, judges, or investigators. Civilians have no state authorities to turn to.

Civilians are forced to comply with the dissidents’ wishes, who frighten them by threatening them and by planting landmines close to where they live. Colombian government officials can continue to claim the deal with the FARC has finally delivered peace, but the armed groups of Tumaco are proving them wrong.