High-ranking Catholic leaders representing every continent on earth made an urgent appeal Monday to the global negotiators and political officials who will gather in Paris in December for the United Nation's 21st climate summit. Their message: After two decades of abysmal failure, don't screw up this time.

"What we are asking for is a fair, legally binding and truly transformational agreement by all the nations on earth," said Cardinal Oswald Gracias, President of the Federation of Asian Bishops' Conferences and the Archbishop of Bombay, India. "Unless we are careful and prudent, we are heading for disaster."

"I know this is ultimately a political decision," Gracias added during a one-hour press conference at the Vatican's Holy See Press Office. "Politicians think strategically, in small terms; 'How many years am I in office?' Our concern is for generations to come for hundreds of years; this is the church's duty."

From Nov. 30 to Dec. 11, 2015, Paris will host COP21, the Conference of the Parties, in which leaders from 196 nations will try, once again, to forge a global agreement to vastly reduce the burning of fossil fuels — a meeting that some see as a last chance to stave off planet-wide disaster.

Those carbon emissions, primarily produced by energy generation, are largely responsible for the earth warming by 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) since the dawn of the industrial age in the mid-1800s. A rise of another 3 degrees C (5.4 degrees F), which many experts believe will be catastrophic to life on earth, is predicted this century if dramatic action isn't taken.

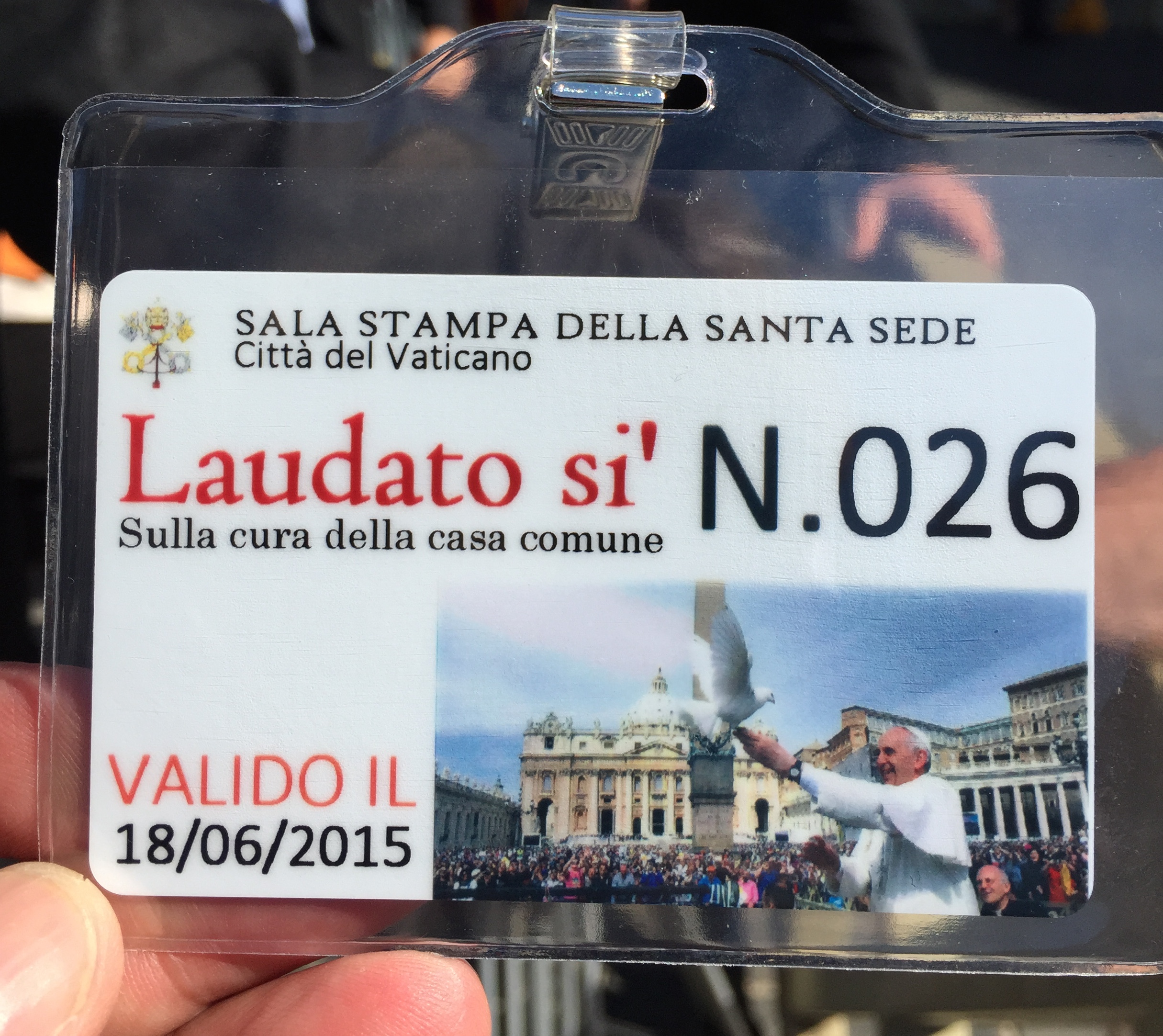

The emotionally charged press conference Monday was historic. It was the first time ever that cardinals and bishops representing the world's continents drafted and signed a 10-point statement on something other than a religious issue. Each of the five speakers cited Pope Francis' landmark encyclical on climate change and the environment — Laudato Si, On Care for Our Common Home — as inspiration for their unprecedented call to action.

"In Oceania, our survival and existence are at stake," said Monsignor John Ribat, President of the Federation of Catholic Bishops' Conferences of Oceania and the Archbishop of Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. Many Pacific islands and atolls will disappear if global glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet keep melting. "God gave us the same dignity as all other countries and continents in the world. But we belong to those groups most affected by climate change and sea-level rise."

Ribat explained that flooding and drought in some island nations is already reducing the ability to grow crops and forcing natives to flee. This is resulting in a little publicized immigration crisis — far from the one occurring in Europe. Still, he noted, many people are reluctant to abandon their sinking homelands, fearful of what awaits them as eco-refugees — discrimination, xenophobia and cultural isolation.

"This is my urgent call," Ribat said to those who will negotiate in Paris: "Guarantee the future of Oceania. Change society to a low-carbon lifestyle."

In many ways, Monday's comments echoed the impassioned pleas of Pope Francis, who wrote in his encyclical, a church teaching document, we "must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor."

Professor Jean-Pascal van Ypersele de Strihou, of the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium and a former UN climate summit participant, was the only non-religious leader to take part in the press conference. He stressed that a ton of carbon emitted in Rome or New York City or an African village had the same effect on global warming everywhere.

"It doesn't matter where it comes from," he said. "Each ton thickens the insulating surface around the earth and warms the surface."

He then cited current, not future, impacts of the just 1 degree C (1.8 degree F) increase seen so far: rising sea levels, longer and more severe droughts, more intense hurricanes and cyclones, and growing food insecurity.

"The changes in climate are already affecting people on all continents and all over our oceans," de Strihou said. "Yet the poor are more vulnerable and the least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions. This is what I call the double injustice of climate change."

He then warned: "The rich should not believe too long that they will escape the impact of climate change. We all share the same planet. If we sink to the bottom of the ocean, we sink together."

Evan Berry, Associate Professor of Philosophy and Religion at American University in Washington, D.C., said he believes the time is right for religious leaders to engage in the complexities of climate change policy.

"In the broader international conversation, where the NGO community has been pushing back against political inaction to no avail, they are getting burned out," said Berry, author of Devoted to Nature: the Religious Roots of American Environmentalism. "In the past two or three years, it was clear that broader coalitions were needed to mount effective pressure on governments. In many parts of the world, religious leaders are stepping into that breach."

Berry did, however, draw an important distinction between what governments can do — immediate regulatory action if they choose it — versus the long-term, parish-by-parish work that the church faces.

"At the grassroots level, we need cultural change, and that's not happening by December," he said. "It's going to take decades. The church has a role to play, but it's a very different role."

The church leaders at the Vatican Monday demonstrated their willingness to step into that role, and to fight vigorously and vocally for action on climate change. Within their 10-point appeal, they strongly urged COP21 climate negotiators and world leaders to:

Keep in mind not only the technical but also the ethical and moral dimensions of climate change.

Adopt a fair, transformational and legally binding agreement that recognizes the need to live in harmony with nature, and guarantee the fulfillment of human rights.

Develop new models of development and lifestyles that are climate compatible, address inequality and bring people out of poverty.

The bishops also called for specific action to mitigate rising temperatures; for wealthy countries to provide the means for poorer countries to adapt to the climate damage already underway; and to provide "clear roadmaps" on how countries will finance and meet their commitments.

Asked whether he thought a thus-far elusive global agreement to limit carbon emissions can be hammered out in Paris, de Strihou, the professor from Belgium said, "I am optimistic that an agreement will the struck. But I am a little less optimistic that it will be enough. Still, it's better to have an agreement to build upon and improve than to have no agreement at all."