When Burmese mortar rounds crashed into his village last July, Magawng La Hkam hobbled into the bush with nothing but his wooden crutches.

Confined to a displaced persons camp near the Chinese border ever since, the 68-year-old ethnic Kachin farmer said he yearns to return home but can't shake the memory of what he saw on that day: the mangled remains of a boy he passed as he fled.

Deep in the resource-rich hills of northern Burma's Kachin State, a civil war grinds on between government forces and Kachin rebels, calling into question the more conciliatory signals emanating from the country. Over the past year an estimated 75,000 civilians have been driven from their homes.

Shifting front lines have pushed thousands more refugees into China, where aid is scarcely able to reach them.

International rights groups accuse the Burmese army of deliberate attacks against civilians, torture, rape, forced conscription and summary executions. Both sides employ child soldiers and continue to seed the ground with land mines that have claimed combatants and civilians alike.

The conflict, which reignited when a 17-year cease-fire collapsed last June, persists despite a political thaw in lowland southern Burma that has taken hardened observers by surprise. Since coming to power last year, the nominally civilian government has freed hundreds of prisoners, eased media censorship and reached agreements with other ethnic minority rebel groups in a wide-ranging push to open up the country.

In remote Kachin, however, the fate of ancestral lands has been a sticking point for the mostly Christian Kachin rebels, who have a reputation for fearsome hit-and-run guerrilla tactics that date from World War II. The Kachins are one of more than 100 ethnic minorities in Burma, a strategic crossroads among China, India and Thailand.

Western governments that for decades kept their distance from Burma have responded favorably to the general thaw. Following by-elections in April in which democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi was elected to parliament, the European Union suspended most of its sanctions. The United States, for its part, has removed barriers to investment and appointed its first ambassador in 22 years.

Having traveled to Burma on an official visit in November, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton in May urged American businesses to "invest in Burma, and do it responsibly," with the caveat that broader sanctions would remain in place for the time being to prevent "backsliding."

Foreign analysts say that enduring U.S. concerns over human rights abuses and ethnic conflicts are not lost on Burmese President Thein Sein, a former general, but that his calls for a military cease-fire in Kachin State are being ignored by current military leaders.

Indeed, Burmese government forces have ramped up their offensive against the Kachin Independence Army, underscoring the limits of civilian authority and the vast wealth at stake in the hinterlands.

Valuable Turf

Known as the "Land of Blue and Gold," Kachin's mountain jungles and river valleys abound with minerals, jade and timber. Kachin State also has massive hydropower projects that stand to benefit energy-starved China, which has invested billions in the region, at the expense of ethnic Kachin natives.

The current fighting erupted last June near the Myitsone dam, a controversial joint venture between the Burmese government and state-owned China Power Investment Corp. that would have sent 90 percent of the electricity generated to China's southwestern Yunnan province.

Thein Sein later halted construction in response to protests over forced evictions and environmental concerns, a rare bow to public pressure that rankled Chinese officials.

Though outnumbered and outgunned, Kachin rebel leaders say they are willing to lay down their weapons only in exchange for greater autonomy and a fair share of economic largesse.

The Burmese "want to solve this dispute militarily," said Brig. Gen. Sumlat Gun Maw of the Kachin army. "We want a real dialogue. Kachin is rich in natural resources, and so they don't want to give us equal political rights," he added in an interview at his command center in a hotel in Laiza, the KIA's administrative capital.

The former boomtown has seen an exodus of Chinese businessmen who once filled its casinos and tax coffers. Hotels rooms are empty and entire shopping blocks shuttered, the local markets now frequented mostly by displaced civilians from the half-dozen camps that have swelled in and around the city with the advance of Burmese forces.

Hka Htum Lu, 42, arrived on foot four months ago with her family after their village came under attack. Several weeks ago, her husband went back in search of belongings. He never returned.

"It's hard to say what's missing most because we lost everything," she said, nursing one of her six children. Like many others, the family subsists on rations of rice and salt provided by the KIA's political wing, and whatever else they can scrounge from the forest.

Across town, a group of Burmese child soldiers passed the day chain-smoking cigarettes between meals at a lightly guarded cinder block compound.

Nay Myo Oo, 16, said he was forced to join the Burmese army after a bogus arrest and trained to lay land mines until he ran away. Now his feelings are mixed: He's relieved that his combat days are over, but worried he'll never see his family again.

Citing a shortage of money and manpower, Kachin officers concede there are perhaps 100 underage soldiers in their ranks but insist they are there to be disciplined, not sent out to fight. (With access strictly controlled, this could not be confirmed.)

Ties to China

The KIA's war chest is largely fed by taxes and illicit cross-border trade in products ranging from dry goods to teak, highlighting its awkward relationship with China, its lifeline to the world.

In Laiza, the Chinese yuan is the currency, and Chinese mobile phone networks keep locals connected. China hosts Kachin university students, and when soldiers are seriously injured, lax border controls allow them to be brought to better hospitals for treatment. Even basic necessities such as medicines and rice are smuggled into Kachin territory.

This dependence is tempered by the fact that Chinese-funded infrastructure projects are at the crux of the conflict in Kachin State.

"We are neighbors in more ways than one, and we can't avoid each other," said Sumlat Gun Maw, the Kachin general, measuring his words carefully. "We welcome investment from China … as long as it doesn't hurt civilians."

China has not taken a formal stance on the war, but KIA officers and analysts say it wants stability along the border to protect its commercial interests.

To date, China has refused to classify thousands of displaced Kachins living on its side of the border as "refugees" and is accused of sending some back to Burma. As a signatory to international refugee treaties, such a designation would require China to meet legal obligations for assistance.

In the meantime, refugees continue to rely on grass-roots organizations for help. May Li Awng, the founder of a local aid group based in Maija Yang, the second-largest town under KIA control, fears that conditions are poised to go from bad to worse as the monsoon season continues.

"I'm not sure anything will change; the Chinese are paranoid about foreigners," she said.

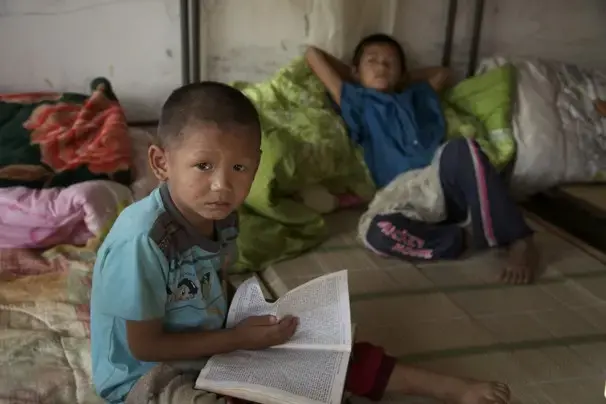

An eerily vacant sprawl of gambling halls and brothels, Maija Yang has attracted droves of civilians lately from Shan state, scene of the fiercest clashes. Many are children separated from parents. They sleep three to a bed in camp.

Last week, a Burmese government team met with KIA representatives in Maija Yang for the third round of informal talks in a month. Progress has been scant.

"We know the way the Burmese think; they are tricky," said a rebel supporter with knowledge of the talks. During the last face-to-face meeting, hosted by China, the Burmese army maneuvered heavy guns deeper into Kachin territory, the supporter alleged.

KIA officials insist that the Burmese army must pull back to the original 1994 cease-fire lines before talks can move forward.