BHOPAL, India—Bhopal, the historic city of begums (Muslim empresses or royal consorts) and lakes, is located in the heart of central India. The metropolis, the capital of the state of Madhya Pradesh, retains its charm from a bygone era. Centuries-old buildings seamlessly blend in with modern high-rises.

Despite its historic significance, however, Bhopal is most known for a tragic disaster. Late in the night on December 2, 1984, tons of poisonous methyl isocyanate gas leaked from the Union Carbide pesticide factory. The wind carried the heavy, toxic gas toward densely populated urban areas. Within hours, thousands were dead and more than half a million people were left injured and impaired.

Decades later, another disaster loomed in Bhopal. In March 2020, as COVID-19 began surging in India, the Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Center (BMHRC) was designated as a COVID-19 only hospital. Immediately, things took a turn for the worse. The tertiary-level hospital was dedicated to providing clinical services to the gas tragedy survivors, caring for 32,000+ patients every month. Suddenly, the facility forcibly discharged gas-tragedy survivors from the ICU and other wards to free up hospital beds.

It refused care for gas leak survivors unless they tested positive for COVID-19. Patients suffering from chronic lung disease or cardiovascular ailments were left vulnerable as COVID-19 transmission gained momentum. While it is difficult to ascertain the exact number of gas tragedy survivors today, activists working with affected families agree that there are around 400,000 people impacted by the gas, the effects of the gas in utero, or subsequent chemical contamination from the plant. Many of them suffer from chronic ailments, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension. Many children born to people affected by the gas suffer from skeletal abnormalities and immune system problems.

As the pandemic gripped Bhopal, Munni Bee, a social activist and gas leak survivor who also suffered from several health sequelae, was being treated in the ICU at BMHRC when it was suddenly designated COVID-19-only. From the ICU, she fought for her life—and the rights of other survivors. Her representatives dragged the government to court to ensure that BMHRC start treating the gas tragedy survivors, irrespective of their COVID-19 status. The Quint reported that while Munni Bee’s petition ensured continuity of care for her, 86 other patients undergoing treatment in different units of the hospital were discharged immediately.

On April 8, 2020, while the courts were trying to figure out the protocol for video conferencing, Munni, 68, passed away due to cardiovascular complications. Tragically, she could not see that her efforts were not in vain, as later that month, the decision to limit BMHRC services for COVID-19 patients was retracted and services resumed.

Her death was a stark reminder that the gas tragedy survivors were still living in the shadows of that one horrific night, neglected by the health care system.

Hunger Returns to Bhopal

A tall, gaunt lady clad in a somber hijab, Aleena Ashraf* recalls the mayhem of that night in December 1984, as she leads me through the serpentine alleys of Chhola Road. I was visiting Bhopal to understand the COVID-19 experiences of the gas tragedy survivors as a part of my Pulitzer Center reporting, working closely with the Sambhavna Trust and their network of community activists. She vividly recalls the pervasive, caustic smell, like burning chilies, that hung in the air when she returned home as morning broke on December 3, hoping to salvage her belongings. She recalls seeing people and cattle lying dead on the streets.

In addition to the lingering stench, a general sense of fear, mistrust, and anxiety permeated the city in the aftermath of the gas leak. “We threw away the food, thinking it was poisoned, and went hungry as we were barricaded in our homes. We did not know what to do and who to trust,” Ashraf told me.

During the pandemic lockdown, the loss of livelihoods and disruption of welfare schemes meant that hunger returned to Bhopal. “When COVID came, death roamed these streets again,” Ashraf says. “It feels like reliving a very bad nightmare.”

As COVID-19 was making its way through Europe, Rachna Dhingra, a social activist who works closely with the gas tragedy survivors, followed with increasing unease the news of higher COVID-19 mortality in individuals with chronic diseases.

“We raised the alarm bells early on, apprehensive that the gas tragedy survivors—with comorbidities like lung injury, kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, and cancers—would be especially vulnerable to COVID-19,” she says.

Her fears came true when the first spate of COVID-19 deaths started to claim the lives of older survivors of the gas tragedy.

At Special Risk

Numerous studies confirm Dhingra’s fears that the gas tragedy survivors are more likely to experience diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, certain cancers, and diabetes that put the survivors at greater risk of suffering severe disease and death from COVID-19.

Working with activists like Dhingra and Satinath Sarangi from the Sambhavna Trust, I was part of a team that conducted an analysis of 1,240 COVID-19 deaths publicly reported between April 2020 and July 2021. We found that compared to gas unexposed individuals, the risk of mortality in the gas-exposed individuals was higher. This finding, awaiting publication in a peer-reviewed journal, is likely to be an underestimate because of the under-reporting of COVID-19 related deaths, yet another situation that mirrors the 1984 experience. Dominique Lapierre notes in his book, Five Past Midnight in Bhopal, that one of the reasons for undercounting the toll of the gas tragedy is that entire families were wiped out. With no survivors left, there was nobody left to report these deaths, and bodies were disposed en masse.

From April to August 2020, the rapidly evolving first months of the pandemic brought new challenges and confusions every day. Faiz Ahmed Kidwai, an Indian Administrative Services official, who took over the health department in May 2020, said decisions needed to be made quickly, often with no or incomplete data. Some decisions left a trail of unintended consequences.

One such strategy was to funnel COVID-19 patients to health care facilities specified by the government to handle the surge in cases. The decision to earmark BMHRC backfired, because, as Dhingra notes, instead of providing extra care for the vulnerable gas tragedy survivors, “the hospital turned them away to die.”

Iqbal Hossain,* a chronic kidney disease patient who needed thrice weekly dialysis, says that even when the services resumed, they were far from normal. He depends on BMHRC because, like thousands of other gas tragedy victims, he cannot afford to get dialysis at a private facility, he says, sitting in his modest two-room home in Bhopal’s Naya Kabadkhana neighborhood.

For four weeks, he could not access BMHRC services, so he had to take out loans to get once-a-week dialysis at a private clinic. Now he is back on his usual regime at BMHRC, but the ordeal has taken its toll. He is unable to walk without getting short of breath, and lives in constant guilt over the loans that his family has taken out for his medical care.

The Sambhavna Clinic in JP Nagar, a nonprofit health care facility, caters to thousands of gas tragedy survivors like Hossain. It provides them with affordable holistic care. An oasis of peace in the middle of a busy city, it is located in one of the areas that was worst affected by the gas tragedy, standing just a few hundred meters away from the Union Carbide factory.

A painting depicting the horrors of the Bhopal gas tragedy, titled “Killer Carbide,” adorns the clinic’s walls. It shows the misery following the 1984 disaster. Every day, hundreds of gas tragedy survivors walk down the corridor where this painting hangs, past the images depicting people fleeing from the noxious fumes, a small mound of corpses in the corner, and a signpost reading “25,000 deaths.”

For many of these patients, the painting echoes their experiences during the pandemic—fear, uncertainty, under reporting of deaths, misinformation, food insecurities and hunger, the lack of a definite treatment—the list goes on.

Lessons from Another Tragedy

If there’s another glimmer of hope, it’s that the tragedy may catalyze policy changes. “We must invest in preparedness,” says Kidwai, now a senior bureaucrat in the administrative system. “We need to strengthen the epidemic response systems, in line with the disaster management systems. With COVID-19, we had to play catch up, but now we must learn from it and be better prepared because this will likely not be the last global contagion,” he says.

Tarun Pithode, the district magistrate of Bhopal during the pandemic, reflects on the resilience of the human spirit and marvels at the sense of community that he witnessed: “We have seen the best of humanity and the worst of humanity,” he writes in his book, The Battle Against COVID. It took the system a while to figure out a way to shield gas tragedy survivors from the virus, but by then, it had inflicted a lot of pain on this long-suffering group.

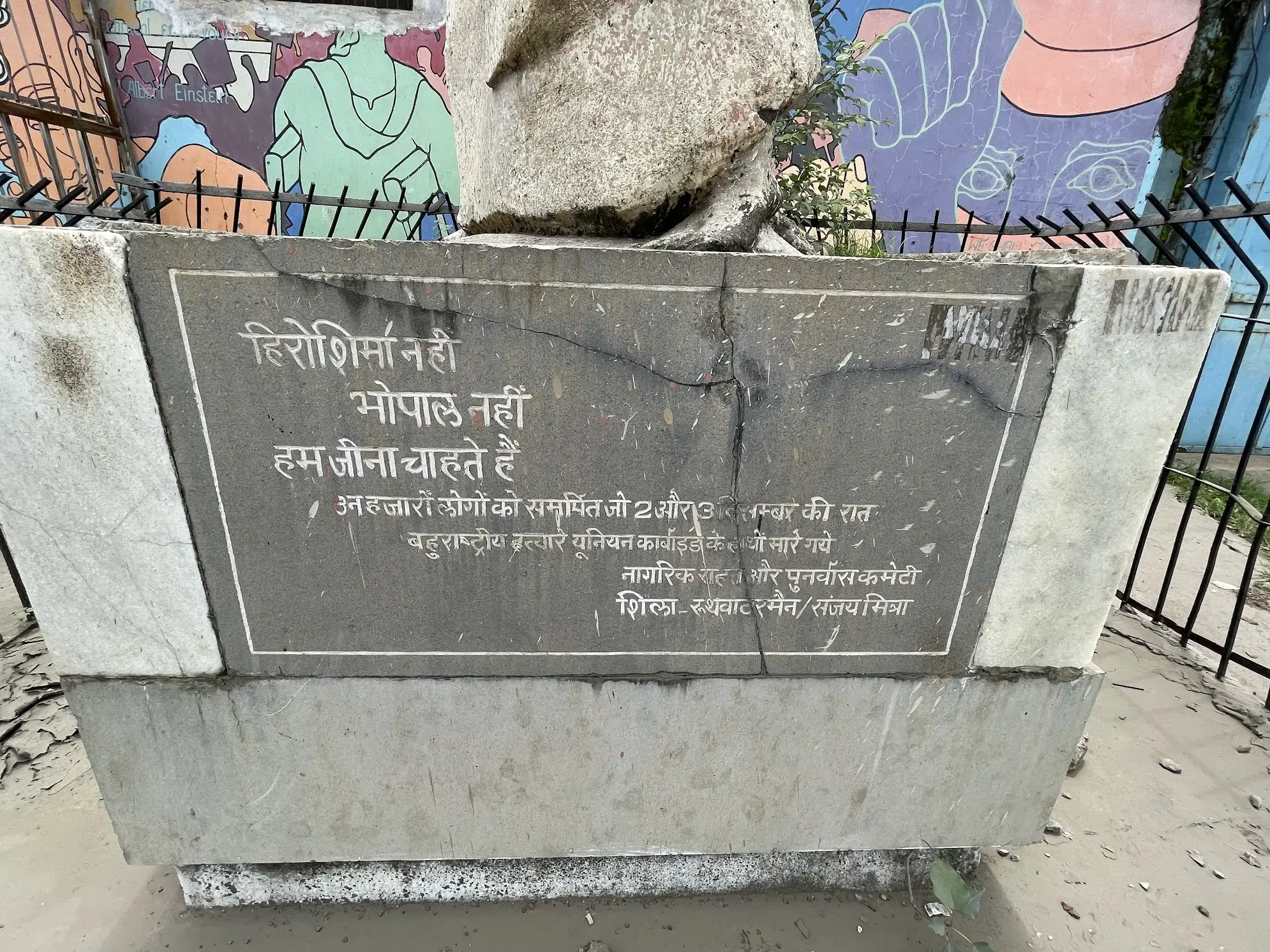

Not far from Munni’s house stands the statue of a featureless woman.

The resolute spirit of the people of Bhopal is best embodied by this iconic statue of a mother, her face covered, holding a child, and gasping for breath as she runs away. Dedicated to the people of Bhopal by the Dutch sculptor and Holocaust survivor Ruth Waterman, it is just 200 meters from the Union Carbide compound.

Beneath the statue, under a thick layer of dirt, grime and dust, there is a black stone tablet, which reads “No More Hiroshimas. No More Bhopals. We want to live.”

Ed. Note: Names with asterisks have been changed for privacy reasons. Most of the survivors interviewed requested anonymity; many said they have ongoing legal cases and did not want to jeopardize their prospects for receiving the compensation.

Pranab Chatterjee, MBBS, DTM&H, MD, is a PhD student in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. His reporting for this story was supported by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health-Pulitzer Center Global Health Reporting Fellowship. Separately, Chatterjee worked on the analysis of 1,240 COVID-19 deaths between April 2020 and July 2021 with Sambhavna Trustthat he references in this piece.