I wish I could turn the clock back to B.D., or before drugs.

Before the opioid epidemic spread through our tribe like wildfire.

Before my husband became addicted. Then two of my sons. Then my grandchild.

When I think about my sons, Roger and Cory, I picture them as I do all my children, as precious babies. I don’t see them as the rest of the world does, as two men in their 30s with drug addiction.

Somehow the hollowness of their cheeks, their pale skin, sores and swelling don’t register in my brain. When I look at my sons, I see all that I’ve known them to be and all of what could have been or could still be if it weren’t for OxyContin, then heroin and now fentanyl.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

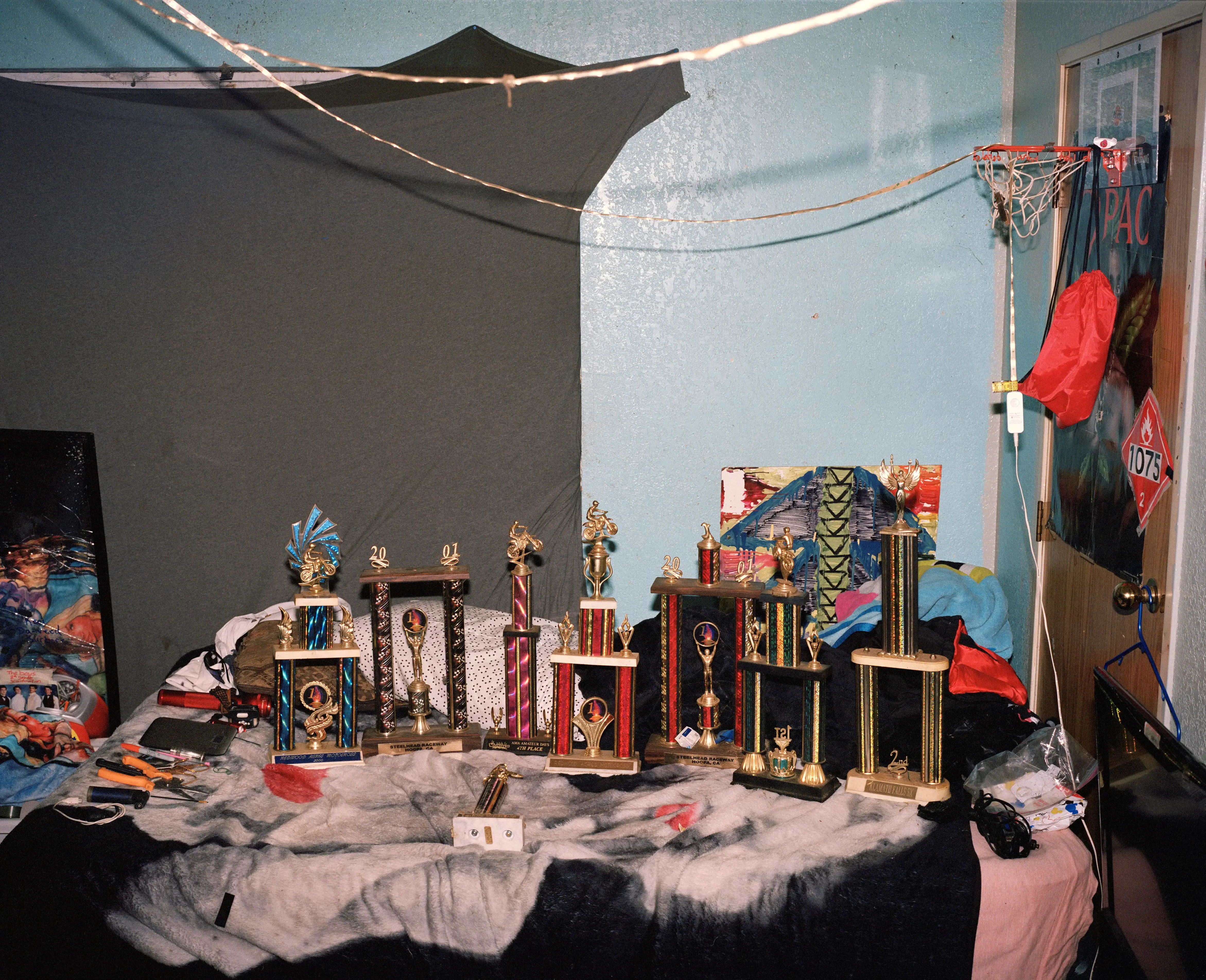

On the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation, where my family has lived, my sons played sports, hunted, fished and participated in motocross events. I had high hopes for my children and could not fathom what would happen to us when OxyContin came to the valley.

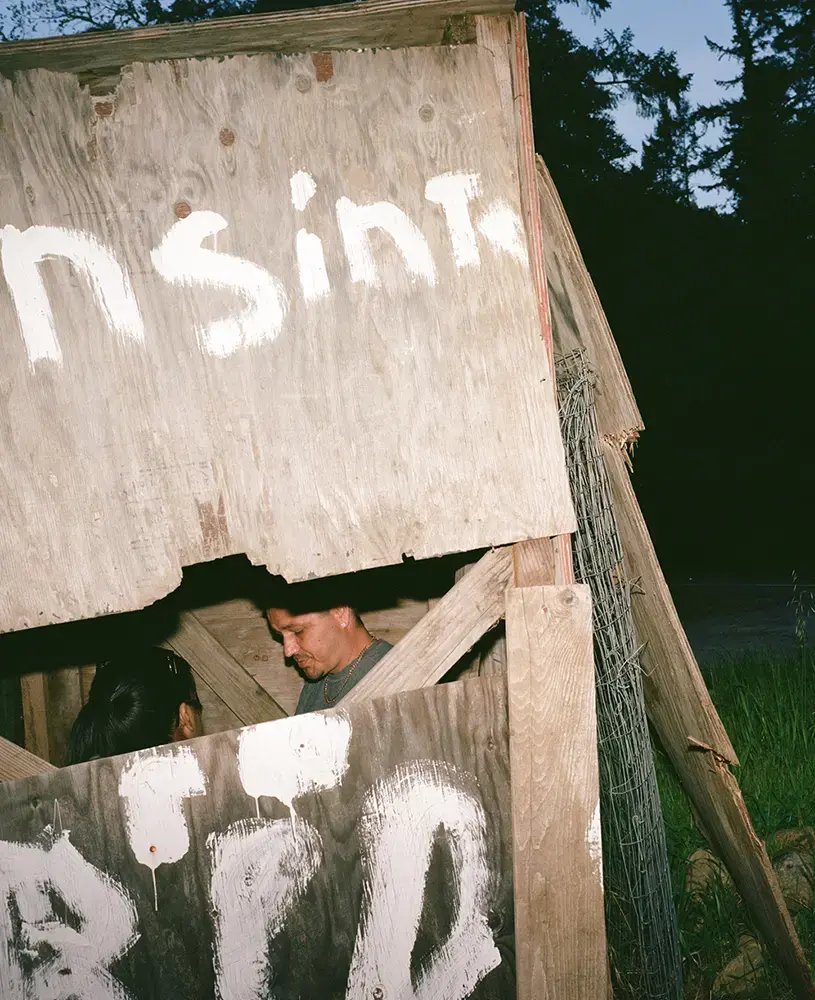

The reservation is in a secluded valley in Far Northern California, with the Trinity River running through it.

The remoteness of this place has long protected us. Non-Native people did not make their way into our valley in large numbers until the latter half of the 1800s, and our privacy has helped shield us from many outside influences.

But today the opioid crisis facing the nation has infiltrated our community, causing destruction and havoc along its path, leaving families like mine shattered.

At 61 years old, I have lost far too much to drugs, and I’ve never done anything more than weed, as a teenager. I have three sons and one daughter, and while I know that my husband and I weren’t perfect parents, I also know that we did the best we could. We worked hard to provide the basics for our family, as well as for extracurricular activities. We took extra shifts and held local food sales for Indian tacos and eel roasts for additional income. We somehow managed to make it all work.

I became a widow at age 57, after 38 years of marriage to my husband, a good man I loved dearly and miss every day. He was a hard worker, employed in the logging industry for over 20 years until he was in an accident on the job. He was prescribed OxyContin, which at the time was being touted as a miracle drug with a low risk of dependency.

My husband was so functional and so discreet that I didn’t know for years he had moved on to heroin. I never saw drowsiness or other signs that people look for in addiction. By the time I realized what was happening, my husband was sick with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the care he needed took precedence over all else.

I remember reading once that if parents had an addiction to alcohol or drugs, their children would have a higher risk for addiction, too. My oldest son, Sport, and my daughter, Megan, were both spared the vicious addiction cycle. But Roger was 18 and Cory was 15 when what started out as recreational use of OxyContin quickly progressed to serious addiction.

During this time, I did everything possible to keep my family together. I never bought into the idea of tough love because I don’t believe it really works for Native families like mine. We are so hard on ourselves to begin with. Instead, I unconditionally love my children. I’m terrified of losing them.

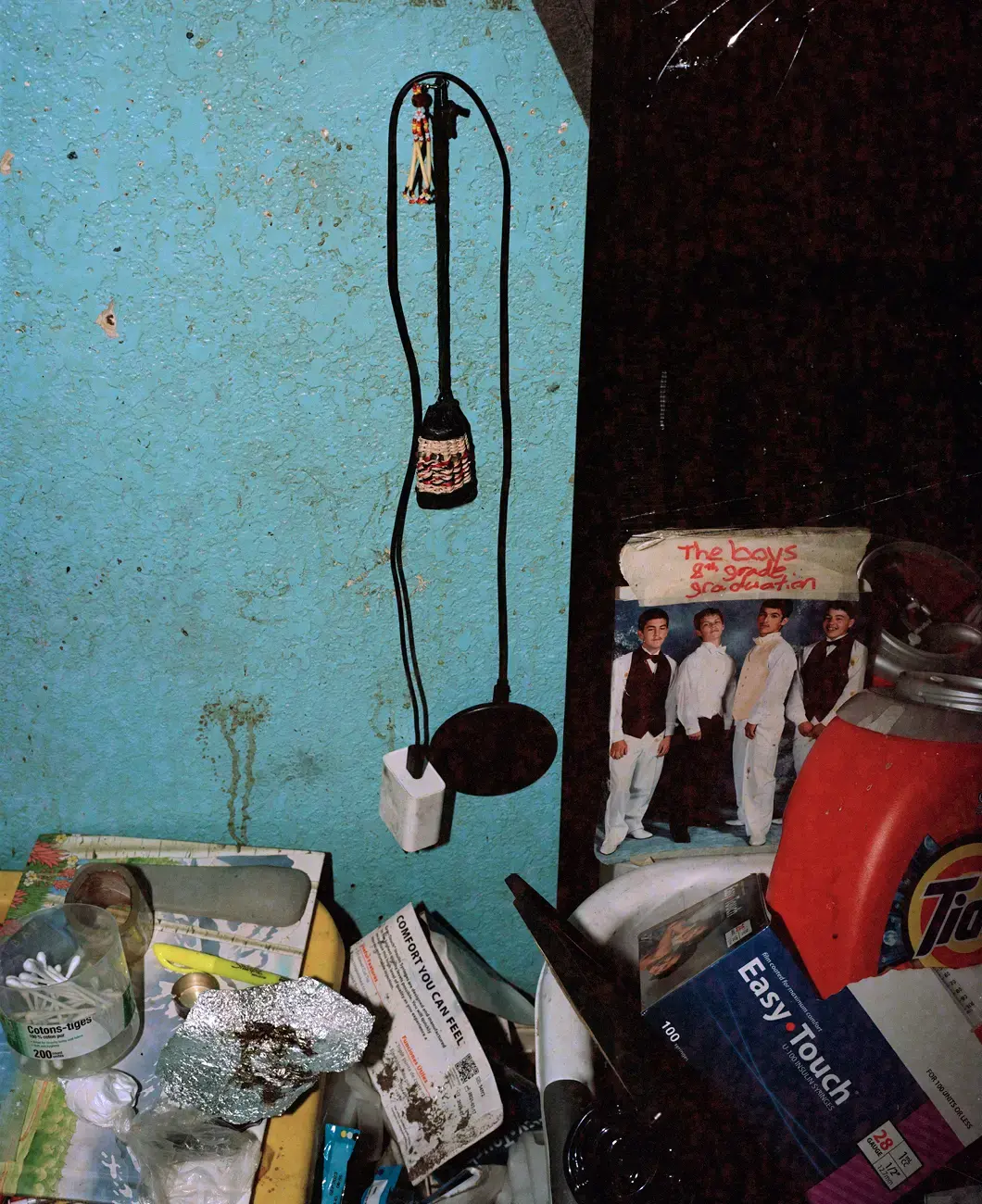

I’ve marveled at how in this economically depressed, poverty-stricken rural reservation, anyone seemed able to afford an OxyContin habit. I recall one pill being $60, and that wasn’t enough to get someone through a day. I lost jewelry, cameras and anything else that could be traded or hocked; it all just disappeared. I bought a safe and started locking up anything that was valuable.

Our lives became a series of crises that quickly became our norm. We lived in survival mode. When OxyContin became more regulated, people switched to heroin. I thought nothing could be worse than heroin, and then fentanyl came along. I thought nothing could be worse than fentanyl, and now the animal tranquilizer tranq, or xylazine, is on the horizon. I’m fearful of what the next monster might be.

Will my sons make it?

My teenage granddaughter recently left an addiction treatment facility in Utah. In the summer of 2022 she overdosed three times on fentanyl. I fought hard to get her into a treatment center with a Native program but was turned away by two Indian Health Service youth residential treatment centers, which said that she needed a higher level of care. In my heart I knew that the next overdose might be her last. Per the rules of the facility she attended, I wasn’t allowed to talk to her on the phone or write her letters while she was there.

Roger’s three children, ages 9, 6 and 3, lived in my home their whole lives until recently. Roger and the children’s mother also lived with me off and on, but when they lost custody, the children were taken into foster care. I never thought that they would be taken from me. I shielded them from their parents’ addiction, and they were happy and thriving. Now they are living more than two hours away, and the Indian Child Welfare Act, which was meant to protect us, has resulted in the opposite fate. The Yurok Tribe, which has control of the children’s placement, said it would not consider me to be a caretaker for the children.

I’ve been told I didn’t set enough boundaries. I’ve been blamed for my son’s addictions. But people with adult children with addiction will understand my predicament: No matter what boundaries you set, if adults want to use drugs, they will find a way to do it. I have cried, threatened and begged and accused my children of not loving me. And yet the only times they have quit was when they chose to try. It was never because of anything I said or did.

I don’t know what to tell the 6-year-old when she calls and says, “Grandma, I just want you. If I stay here four more days, will you not be busy and come bring me home?” Or when the 9-year-old cries, “I just want my daddy.” I promised my grandchildren that I would fight every day until they could come home, but I’m starting to run out of options, and I don’t know if it will ever happen.

My heart is broken. People often tell me how strong I am, but I believe I’m the opposite. If I were a stronger person, I would have found my way out of this nightmare.

I’m just as lost as every other parent with adult children addicted to drugs. I’ve chosen to work as a manager of medication-assisted treatment for the Hoopa Tribe. I believe that if I can help one person get off opioids, then I can still hold out hope for my children. Roger is in recovery and in a methadone program in Eureka, Calif., where he is living.

Every time I hear a siren or my phone rings at night, I have a flash of fear that hits in the deep pit of my stomach. Because of that, I hold my sons a little closer and a little longer when I see them and never fail to tell them how much I love them.