The ongoing project Signs of Your Identity: Forced Assimilation Education for Indigenous Youth began in 2014 after photographer Daniella Zalcman traveled to Canada for a story about HIV rates in First Nations communities. After interviews with First Nations people, she realized the real story, one that touched on a far darker legacy in Canadian history—the forced assimilation of Indigenous children at residential schools. The Canadian residential schools were in operation for over a hundred years, with the last school closing in 1996.

Over the past month, the horrors from these residential schools have re-emerged in both American and Canadian media with the discovery of more than 1,000 unmarked graves at the sites of three residential boarding schools. They were found at two schools in British Columbia, and one in Saskatchewan, the province in Canada where Zalcman focused her work. For years it was known that countless children went missing from Indigenous communities, but the full extent was never fully calculated.

Zalcman’s photos of First Nations people in Saskatchewan most recently accompanied a National Geographic article about survivors reflecting on the recent discoveries out of Canada.

Tom Hundley, a senior editor at the Pulitzer Center, recalls, “Daniella’s project turned out to be one of those ventures where we weren’t quite sure what we’d be getting—and we ended up getting much more than we expected. I wasn’t sure how Daniella could tell this story with photographs, but the technique of overlaying her portraits of survivors with artifacts from their memory enabled her to tell a story that is profound, nuanced, compelling, and enduring.”

Pulitzer Center Outreach Intern Katherine Jossi spoke with Zalcman about Signs of Your Identity, Zalcman’s reflections on its origins, and where the project is heading.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Katherine Jossi: Can you tell me about your history with photojournalism; what got you first interested?

Daniella Zalcman: I have wanted to be a journalist since I was 12—as long as I have known journalism is something you can do. But it wasn't until college when I started working for the student newspaper that I got into photography. There’s something democratic and visceral about photography that I connect to and appreciate. That made me want to become a photojournalist.

As a teenager, newspapers felt like the pinnacle of what I could do as a journalist. That's what I did the first five years of my career. I had this slow realization—with the help of the Pulitzer Center—that I love newspapers, and they are critical, but the pros and the cons of the daily news cycle is that you have to put out a newspaper every day. Your relationship to the stories and assignments you are sent on is fleeting. As I got to know myself as a storyteller, I realized I would rather spend weeks or months or even years on stories, not a few hours.

KJ: Tell me how this project came to be, and how it got the name Signs of Your Identity?

DZ: From 2011-2014, I spent a lot of time documenting the evolution of an anti-gay law in Uganda, with the support of the Pulitzer Center. Near the end of my time working on that, I started to look at the correlation between criminalizing sexual minorities and public health issues, in this case, in rates of HIV. The Pulitzer Center sent me to the AIDS 2014 conference in Melbourne, where I presented this work.

While I was there, I read a UNAIDS report that mentioned the fact that First Nations people in Canada have one of the fastest-growing rates of HIV of any group of people in the world. As an American, I was shocked: Canada has much better health care than we do. How was this epidemic happening in Canada, where, in a 10-year period, HIV rates among First Nations people in Canada went up by nearly 25 percent?

I applied for a Pulitzer Center grant and spent a month in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, interviewing HIV-positive First Nations people. At the time, it felt like a public health story. I was a news photographer and, by training, someone who photographed things in front of me as they happened. Because of how HIV spreads among urban Indigenous communities, that meant I made a lot of photos of Indigenous people living with opioid addiction and injection drug use.

Pretty quickly, I realized almost every single person I met had told me about their time in residential schools. I got home and thought, I messed this up, this isn't the story. These are images that I can’t publish. It feels two-dimensional. It's not going to help anyone understand things that I'm just starting to process, that this public health indicator is part of a bigger legacy.

So I went back to the Pulitzer Center and said, "I screwed up. I need to do this again." Luckily, we had an established relationship, and they trusted me. A year later, I went back to Saskatchewan and focused specifically on boarding school survivors. That's when I started to make double exposures and work with black-and-white portraits. That was the birth of the project.

With the title, I don't know if I would have made the same decision today. It came from an apology issued by the Archbishop of the Anglican Church of Canada, Michael Peers. It included the line: “I'm sorry, that we took from you the signs of your identity.” I think that's powerful. I don't know if I should have used the words of a white religious leader who was part of this legacy, but I found the sentiment important.

KJ: What was the significance of telling this story? And when did you decide to further look into other Indigenous communities globally that have been affected by policies like residential schooling?

DZ: I was angry, this happened in Canada for 120 years and I had never heard about it. I eventually learned that in most places where there has been a colonial government and an existing Indigenous population, there has been a form of coercive assimilation education meant to erase their language and culture. There is a terrifying and a singular uniformity to that tactic. Humans are good at figuring out how to morph systems of oppression. We do things until they become socially unacceptable or illegal. In the U.S., once explicit genocide was no longer an option, the government turned to tools like boarding schools.

Being able to have conversations about how these systems are still present is important. We teach our children to talk about Indigenous people as if they are something of the past. We have no understanding of what it means to have more than 6 million Indigenous people in the United States today. Having continuous and nuanced conversations about the role Indigenous people play in society is vital.

KJ: What were the challenges in creating this project? And how did you navigate telling the story of a community you aren’t a part of?

DZ: We are just starting to deal with the fact that historically, journalists almost exclusively worked as outsiders in the communities they reported on and a lot of that is rooted in colonial practice and needs to change. I have almost always been an outsider. That requires a higher level of care, research, empathy, and diligence. This project is a good example of what could have gone wrong. I thought that the story was x, and came away with a body of work that was mediocre and harmful. Had I published [the HIV reporting], I think it would have prevented me from being able to return to those communities later. I'm glad I didn't. Had I been on assignment for a newspaper, I would have had to file my work, and it would run, and that would be the end of the story. I'm grateful to the Pulitzer Center, that I have the privilege and ability to work on longer and slower projects.

It allows me to course-correct, which is important for journalists when they work as outsiders and learn as they go. We have to figure out the historical context and the nuances of a story when we’re not a part of that community. We don't always know what we don't know. That was the case for me and Indigenous communities. I grew up on the East Coast, I had little exposure to Indigenous people, history, and culture. It was a steep learning curve on how to be fully respectful of the histories of the communities I was working with.

There are practices that have been in place in the journalism world that are in the process of shifting and need to shift. One is that storytelling is one-sided.

I want my work to be collaborative, I want to be able to go to the people who allow me into their lives and share their stories with me and say, "Is this an accurate representation of who you are? Does this feel like a good portrayal of your story?" I believe that people who are part of marginalized communities and who share stories of deep trauma have a right to participate in how their stories are told. As journalists, we frame ourselves as experts on the stories we tell. But the people whose stories we tell, they are the experts. We are just the conduit. Making sure that we tell their stories respectfully and accurately is the most important part of our job.

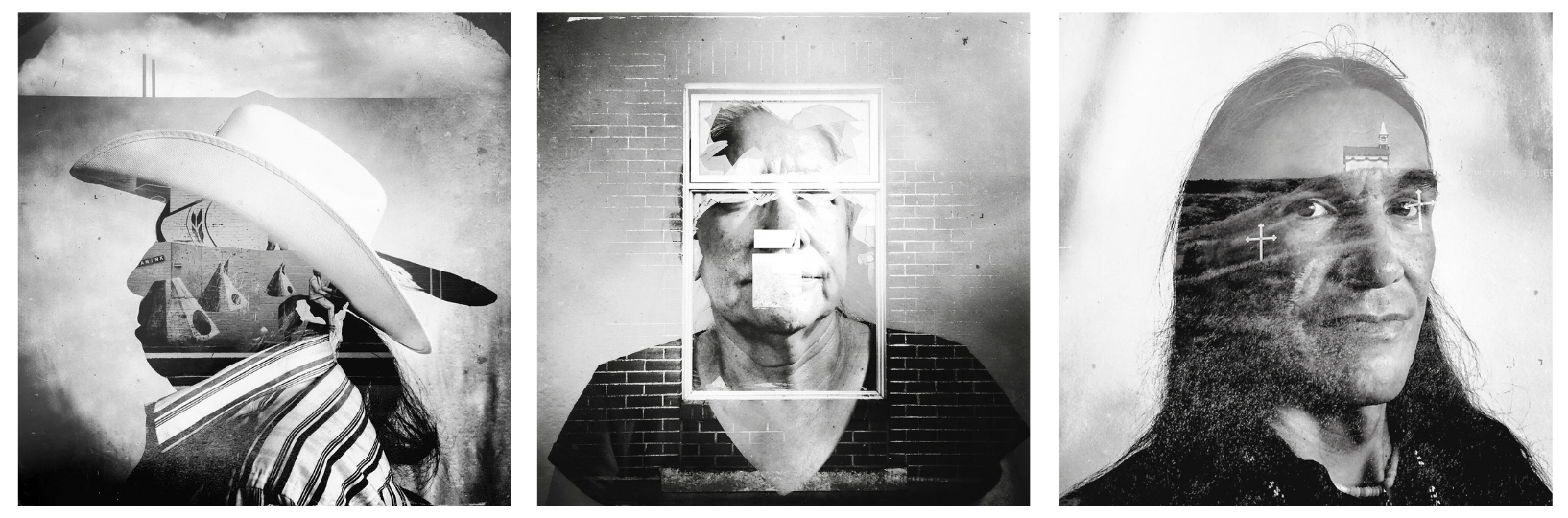

KJ: Talk about your decision to photograph in black and white.

DZ: These images primarily touch on memories that are decades old. Part of the decision was, what was the photographic medium available? How do I return people to that time period? And that is rooted in black-and-white archival imagery and technology. There is a particular kind of visual clutter that you get when you're working in color. It becomes saturated, overwhelming. It can detract from the photograph. Black and white was an aesthetic and this is a story fundamentally about memory. I wanted to visually recall that the stories shared are things that happened in the ‘50s and the ‘60s. Black and white felt like the most clean way to convey this information.

KJ: You have discussed how this project was partially done using your iPhone. What did that process look like?

DZ: I arrived in Saskatchewan with my digital SLR and twin-lens reflex camera. I thought I was going to make true in-camera double exposures on film and realized I ran the risk of ruining the portraits, and I couldn’t do that. And then I realized it would take weeks to get home and process my film. I wanted an immediate connection between the conversations I was having with each survivor and going in search of that visceral representation of their experience of their memory. It felt important that it remained raw. It was practical to use my phone because I could turn it around immediately. When photographing people, an SLR can sometimes be intimidating. But a phone that everyone recognizes and is comfortable with is a much less hostile tool to use. For all those reasons, my primary camera ended up being an iPhone.

KJ: With the advancement of cellphone cameras, is photojournalism becoming more accessible?

DZ: I think it's great. You will hear from, I would argue, mostly older photojournalists that it's terrible that everyone has a camera, and everyone thinks they are a photographer. We all can be photographers, but not all of us can be journalists. There’s a specific ethical code that one needs to thoroughly understand to be a journalist.

The barrier to entry for photography used to be high. It was so difficult. You had to be able to afford expensive equipment, understand how to mix chemicals, and process film and print. The amount of education and money needed to be a photographer meant that only specific people could access the industry.

I love this change—make photography as democratic as possible, because for so long photojournalism has been in the hands of white Western men. That's not an ethical way for us to record our own visual history.

KJ: Is there a specific photo that you feel best conveys the message you were trying to achieve?

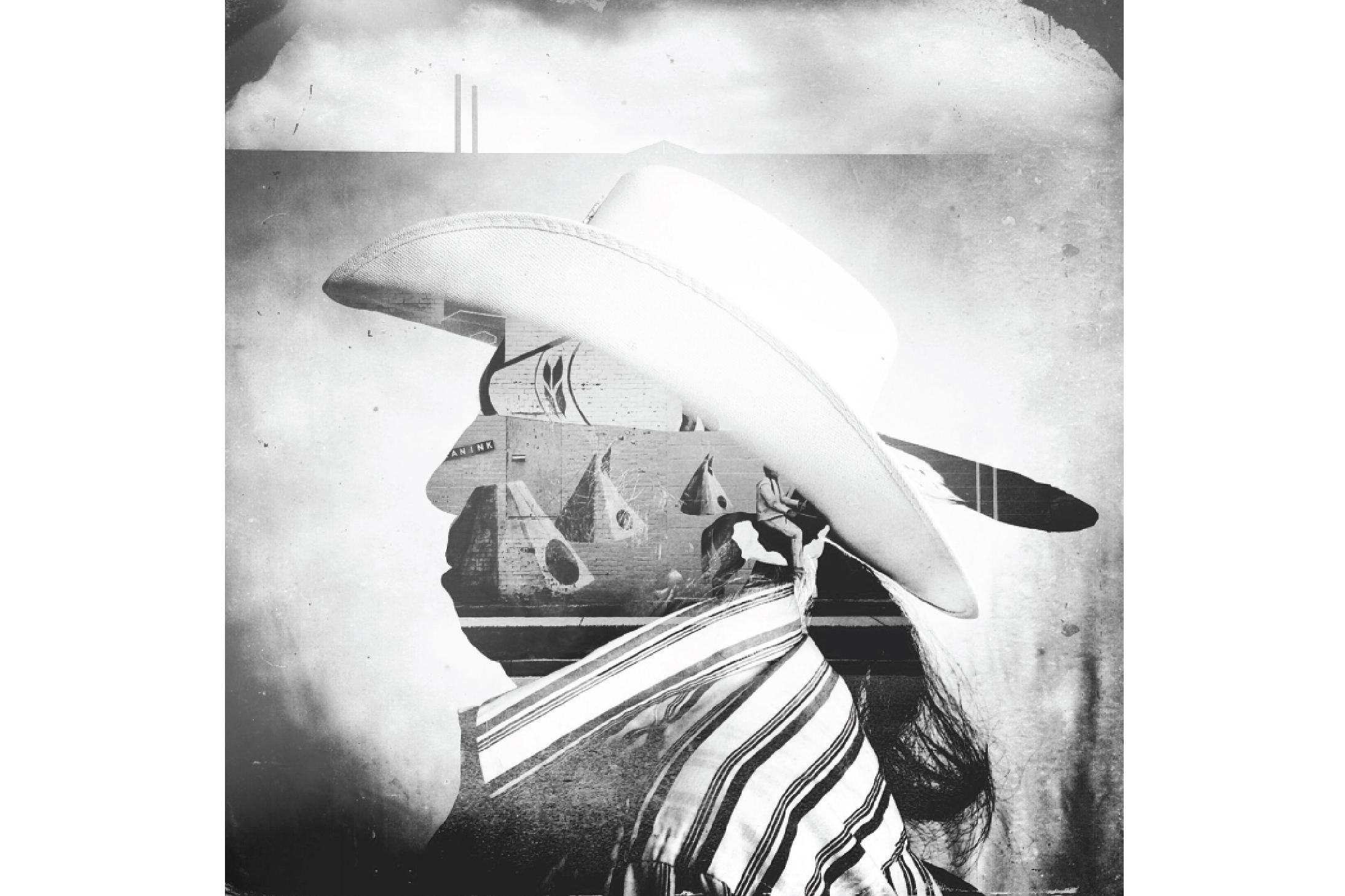

DZ: There are three. The first is the image that is most well-known from the project, of a gentleman named Mike Pinay, who unfortunately has passed away. He was one of the first people I interviewed and photographed for Signs of Your Identity. He was an incredible community leader and storyteller. He also immediately understood what I was trying to do visually and was supportive. I was so grateful for that.

The second photograph is of a woman named Valerie, who has since passed away. It was one of the only instances where I could photograph the building where she attended residential school. Most of the other residential school buildings have been demolished.

The third is a gentleman named Gary, who remains a good friend, who acted as something of a steward between me and First Nations communities in Regina, Saskatchewan. For him, the secondary image is this view of a little chapel on the hill in the Qu’Appelle Valley. He described to me the view that he had from morning Mass. He is someone who spent a lot of time helping me thoroughly understand the history. I wouldn't have been able to do this work as carefully without him.

KJ: What’s next for this project?

DZ: It's ongoing, I've been working on it for seven years, continuously, outside of the pandemic. I would like to continue documenting the legacy [of residential schools and similar institutions] in other countries. But I am also mindful as an outsider who has spent a lot of time documenting trauma in Indigenous communities that there are problems with that. I have a responsibility to look at reconciliation and healing as well, and what it means to undo colonial systems. I am figuring out how to record and archive the trauma, but also what it means to undo that harm. That is a critical part of what I'm trying to focus on going forward.