This letter features reporting from "She Was Among the First to Integrate U. City Schools — and the Memories Are Bittersweet" by Ellen Futterman

Dear Congresswoman Lee,

"History doesn't move in a straight line. It zigs and zags. Sometimes goes forward, sometimes moves back."

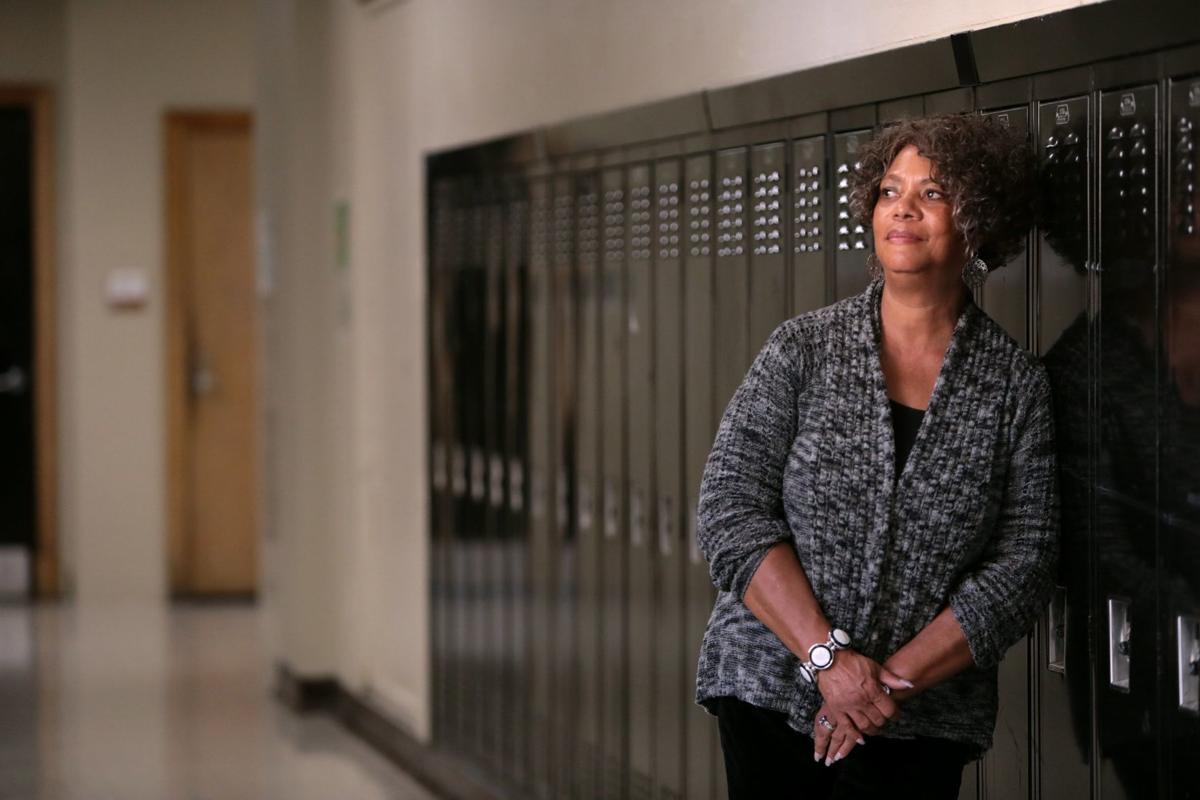

This line from our 44th President, Barack Obama, reminds us that movements toward social equity and justice never have a clear-cut end, nor simple solution. For instance, the fight to eliminate racial segregation within the educational system has helped to encourage equality and fairness, but many of the problems that were prominent in the 1960s still impact African Americans today. An article written by Ellen Futterman for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Pulitzer Center entitled "She Was Among the First to Integrate U. City Schools — and the Memories Are Bittersweet" demonstrates how in spite of legislation desegregating public schools, historical discrimination and current policies continue to result in unequal educational outcomes for Black and white students. The article details the history of Judy Gladney, a 67-year old Black woman from University City, Missouri. Gladney was among the first crop of African Americans to attend racially integrated schools in Missouri. Although she struggled with feelings of isolation and alienation from her classmates, she worked hard and excelled in school, getting accepted to Howard University and becoming a well-known civil rights activist. Gladney's story is one of a woman whose resilience and determination allowed her to overcome her obstacles and take advantage of a shift in the social climate that finally allowed African Americans a chance at success.

Unfortunately, while the 1950s and 1960s marked an end to de jure racial discrimination in schooling, prohibiting explicitly "all-white" and "all-Black" schools, de facto discrimination, or discriminatory outcomes not ordained by law, was still prevalent. The article touches on how Gladney's family faced residential discrimination and couldn't find a real estate agent that was willing to sell them a house in an affluent, white neighborhood. This kind of discrimination was prominent at the time, and the effects still linger to this day. As a result of policies preventing Black people from moving into white neighborhoods, Black students generally don't have the same opportunity to attend high-quality public schools as white students. According to Laura Meckler of the Washington Post in February of this year, "Overwhelmingly white school districts received $23 billion more than predominantly non-white school districts in state and local funding in 2016, despite serving roughly the same number of children … The funding gap is largely the result of the reliance on property taxes as a primary source of funding for schools. Communities in overwhelmingly white areas tend to be wealthier, and school districts' ability to raise money depends on the value of local property and the ability of residents to pay higher taxes." The purpose of education is to be the great equalizer that ensures all students have the opportunity to be successful if they work hard and play by the rules. However, we have struggled to maintain this ideal as centuries of inequities show. While we've improved significantly over the past few centuries and particularly decades, the system of funding for educational facilities reveals that the promise of opportunity is still out of reach for far too many. As a student of Southwest CTA, I'm lucky enough to have a high-quality education with experienced teachers and advanced technology. It's outright outrageous that there are millions of students across the country that don't have access to this high-quality education simply because they were born into the wrong zip code.

Congresswoman Lee, I'm writing to you because I believe every student who works as hard as Gladney did deserves an opportunity to be successful. However, the current regime of school funding overwhelmingly denies that opportunity to African Americans. As the article shows, the United States has made leaps in ensuring equal access to education regardless of race or ethnicity, but work still remains to be done in truly eradicating racially unjust education policies. The best path forward in doing this is utilizing the force of the federal government to force states to stop this way of funding their schools. Just like the federal government used its power over the states to end "separate, but equal" educational facilities, such as then-Attorney General Bobby Kennedy forcing the state of Alabama to allow Black students into their flagship university, Congress can pass legislation ending federal spending to states that don't stop using property taxes to fund schools. States would have to use tax dollars collected through sales and income taxes to fund schools, ensuring that no student gets left behind. I urge you to write legislation that does this because the massive inequities in our education system are utterly unjust and unconscionable. A half-century ago, civil rights activists began the fight to eliminate discrimination in the American education system. With your support, we can finish it

Sincerely,

Ahmed Ahmed

Ahmed Ahmed was born and raised in Las Vegas, Nevada, and is currently a sophomore at Southwest Career and Technical Academy. Ahmed became interested in debate after watching the 2010 National Lincoln Douglas Debate Finals, and is now president of his school's Speech and Debate club, where he competes in Lincoln Douglas Debate and Original Oratory. He is also a member of his school's Environmental Club.

Ahmed developed a love for both writing and politics at an early age. Insatiably curious about the world, Ahmed has loved learning about philosophy, history and economics since he was young. Ahmed enjoys reading and playing Pokémon when he has time to wind down.