Most of his neighbors are still sound asleep at 5 a.m., when Lukasa rises to begin his 12-hour workday. The slender 15-year-old, with an oval face and piercing stare, slips out of his family’s mud-brick home before dawn six days a week. Then he makes the two-hour walk from his tiny village in the southern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to a government-owned mining site. (Fortune is withholding the name of the village in order to protect Lukasa and other children.) Once at the mine, Lukasa spends eight hours hacking away in a hole to accumulate chunks of a mineral that is crucial to keeping our modern lives moving: cobalt.

By about 3 p.m., Lukasa has filled a sack with his day’s haul. He hoists the load, which can weigh up to 22 pounds, on his back and lugs it for an hour by foot to a trading depot. “I sell it to Chinese people,” he says, referring to the buyers from Chinese commodity trading companies who dominate the market in the area. Lukasa is wearing a T-shirt with “Prada” written on the front and sitting under a shade tree in his village on a recent Sunday, his one day off, as he explains his routine. With a hint of pride he says, “On good days I can earn 15,000 francs.” That adds up to about $9.

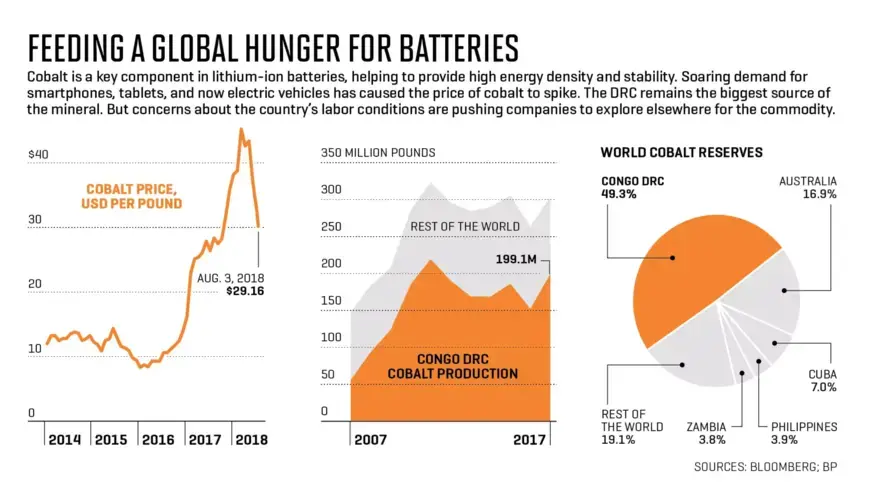

From his vantage point in one of the poorest countries in the world, Lukasa has little awareness that a multibillion-dollar scramble is underway for the grayish metal he digs out of the ground some 300 days a year. Lukasa has, he says, recently begun to grasp that his cobalt mining earnings are a pittance compared with the sums that traders make selling it on the world market. But that business is hard to fathom for those living near Kolwezi, the hardscrabble center of the cobalt industry in Congo. It’s more difficult still for diggers living in poverty, like Lukasa, to understand a surge in demand for the mineral that has sent the price of cobalt on commodities markets rocketing up some 400%, from about $10 a pound in 2016 to a peak of about $44 in April.

That soaring appetite for cobalt is a product of today’s device-driven tech economy: The metal is a key component in the lithium-ion batteries that power countless millions of smartphones, computers, and tablets. Cobalt provides a stability and high energy density that allows batteries to operate safely and for longer periods. Without it, our digital lives—at least for the moment—would be unable to function as they do.

And yet, as valuable as cobalt is today, its crucial role is only now coming into focus. The global transition to renewables—the biggest energy shift in a century—could depend in good measure on how readily cobalt will be available over the next several years, and how expensive it will be to produce and refine. As many governments around the world—if not the one in Washington, D.C.—begin rolling out their climate-change targets to curb carbon emissions, so automakers are hugely ramping up production of electric vehicles. General Motors, for example, says it is planning for an all-electric future. And Volkswagen aims to have one-quarter of its production devoted to electric vehicles by 2025.

Absent a breakthrough invention in battery technology, each electric-vehicle battery will need about 18 pounds of cobalt—over 1,000 times as much as the quarter-ounce of cobalt in a smartphone. Volkswagen, for example, expects it will need to build six giant battery factories within a decade simply to supply its electric-car plants.

That means the spike in cobalt may have only just begun. Demand for cobalt for lithium-ion batteries alone could triple by 2025, and then double again, reaching about 357,000 tons a year by 2030—nearly seven times the current level, according to the London-based cobalt-trading company Darton Commodities. On the ground in Congo, the pressure to produce cobalt has reached a fever pitch. “If you want to be king of the world in the next 10 years, you have to have cobalt,” says Jean-Luc Kahamba Kukenge, deputy general manager of the Congolese mine Commus Global, which is owned by the China’s Zijin Mining Group, when I meet him in Kolwezi. “In the next 10 years, it will be everything.”

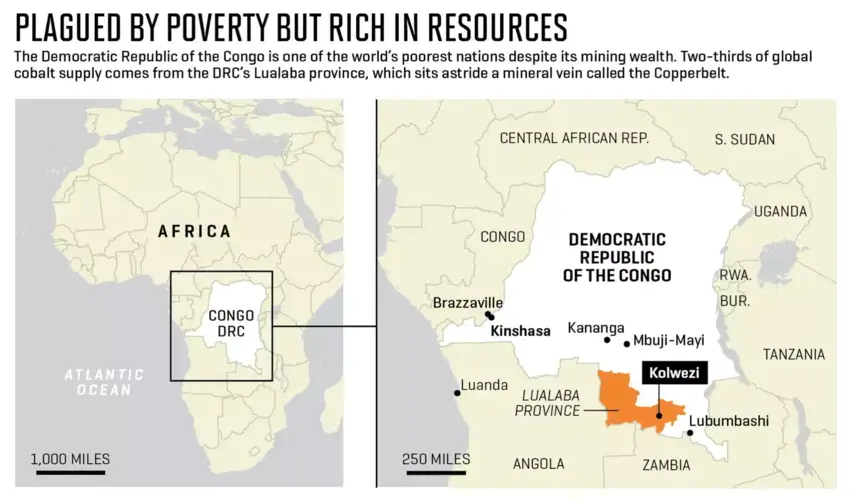

The reliance on a single raw material is nothing new, of course: The auto industry owes its very existence to pumping crude oil out of the earth. But there is a key difference between the car revolution that began a century ago and the electric-vehicle revolution that is just beginning. Oil reserves are tapped in dozens of countries and under every ocean. By contrast, cobalt has until now been heavily concentrated in one sliver of territory. Worse still, that territory is within a country beset by conflict, corruption, poverty, and dysfunction: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC, as the former Belgian colony is known. That reality poses urgent ethical conundrums for the technology, automotive, and mining companies that need cobalt—problems that, if not resolved, could threaten the very ability of those companies to win over millions of consumers to cleaner energy.

Roughly two-thirds of the world’s cobalt is produced in the DRC’s southeastern province of Lualaba, near the border with Zambia. The region sits atop a dizzyingly rich mineral vein known as the Copperbelt—and cobalt is mostly a by-product of copper and nickel extraction. Mining accounts for about 80% of the DRC’s earnings. Stretching across Africa’s broad midsection, the DRC has for decades epitomized the term “resource curse.” Despite giant riches of tin, gold, nickel, copper, and now cobalt, the average person there earns just $700 a year.

Life is grindingly difficult for the millions of Congolese who have no running water or electricity at home; the average life expectancy is about 60. The DRC ranked near the bottom on the UN’s Human Development Index in 2015, at 176th out of 188 countries. And it fares little better on the anti-corruption index of the NGO Transparency International, which cites rampant patronage among a small elite, headed by President Joseph Kabila, who has held power for nearly 18 years. Kabila has picked a close ally to succeed him, in December elections, which could spark violence.

When our small plane bumps to a halt one wintry afternoon in mid-July on the airstrip in Kolwezi, the small provincial capital of Lualaba, there is nothing to suggest we have landed in the epicenter of the world’s cobalt wealth. A small cinder-block structure serves as the “Aéroport National de Kolwezi,” as the hand-painted sign names it.

In 2016, I had landed in the same spot, on assignment for Fortune, traveling in an eight-seater aircraft leased by the Switzerland-based commodities giant Glencore. On that trip, the company’s representatives whisked me off to the bright-lit, air-conditioned complex of Mutanda Mining, the world’s biggest cobalt production facility, with state-of-the-art technology and a meticulous corporate management system that felt like an alien planet amid the chaotic galaxy beyond the gates. Mutanda’s CEO Pedro Quinteros, a seasoned Peruvian engineer, told me then that the mineral concentration in Congo’s Copperbelt was so high that he had “never seen anything like it in my career.” Now I was back to see the other side of the story. Glencore still mines and exports more cobalt than any company in the world, and it says it is planning to double its production over the next two years in expectation of a looming global shortfall in supply.

That industrial-scale output dwarfs the production of the more than 100,000 so-called artisanal cobalt miners around Kolwezi—traditional, independent diggers who have converged on the area to search for cobalt, often with primitive tools. The diggers include an unknown number of children like 15-year-old Lukasa, who support their families by digging small quantities of cobalt by hand, then selling them to middlemen, virtually all Chinese; children in a small village near Kolwezi greet us in Chinese with "Ni hao!" since the only non-Africans most have ever seen are from China.

While it is impossible to know how many underage miners there are, Congolese activists working to end child labor say poverty has driven up the numbers. “Because of the economic crisis, there are about 10,000 of them,” says Hélène Kayekeza Mutshaka, who coordinates a monitoring program in Kolwezi that the government began last year, to try to stop children from mining cobalt. Mutshaka says she faces strong resistance from poor families, who have long sent their children to dig for minerals in order to supplement their meager earnings. “They believe they can try to make it into the middle class if they work as artisanal miners,” Mutshaka says.

Around Kolwezi, that seems an almost impossible dream.

One morning in July, on the edge of an artisanal mine called Kingiamiyambo, about eight miles outside of Kolwezi, we meet 11-year-old Daniel, a small boy walking up the hill from the digging site, caked in dust and carrying a load of cobalt on his back, on his way to sell it to Chinese traders; he tells us he has never attended school. Children like Daniel toil at the very bottom of the global cobalt market. For their families, many of whom depend on the tiny sums their children bring home, there seems little hope of actual life improvement. Yet asking them to stop mining seems equally difficult, so long as cobalt appears a ready source of income. “What do they do then, these children you keep at home, without work?” asks Jean Pierre Muteba, a veteran copper miner who heads an organization in southern DRC called New Dynamics, which monitors the mining sector. “They will seek survival. And what is survival here?” he says. “It is obvious: a mine next door.”

Despite the grueling conditions, the temptation for children to keep working is strong. Many earn just $2 per day, often acting as human mules for cobalt diggers. “When kids are not in school, they all go work in the mines,” says Franck Mande, who oversees a project funded by Apple that aims to teach child miners new skills. “They work from 14, 15, 16 years—even from 10 years old,” Mande says.

Congolese authorities say that they are trying hard to stop children from mining cobalt, but that it is almost impossible to end child labor completely. And they point out that artisanal miners—the vast majority of them adults—account for just 20% of the country’s cobalt output.

But for companies sourcing cobalt from the DRC, the existence of artisanal miners creates another headache: It is virtually impossible to assure consumers of iPads, smartphones, or electric vehicles that no children have dug, crushed, washed, or transported the cobalt inside their devices. For some companies, it has seemed simpler, in fact, to end all business with artisanal miners—a decision that NGOs and Congolese officials say devastates millions of people who depend on the work.

Corporate concerns have risen sharply since 2016, when Amnesty International issued a deeply researched report naming more than two dozen electronics and automotive companies that, Amnesty concluded, had failed to do enough due diligence to ensure that their supply chains didn’t include cobalt produced with child labor at artisanal mines. The report caused a firestorm—and set some companies scrambling to find ways to avoid the DRC altogether. As the debate over Congo’s cobalt rages on, the question is whether the country can overhaul its mining practices before global businesses succeed in going elsewhere. In a country where dysfunction and corruption have endured for decades, the prospect for far-reaching, rapid change seems hard to imagine.

Congolese officials are not the only ones at fault, however. Amnesty blasted Western tech giants for blithely ignoring the problems surrounding child labor and corruption—in large part because consumers had rushed to buy tech devices, without asking questions about the industry’s darker side. “Millions of people enjoy the benefits of new technologies, but rarely ask how they are made,” the organization said at the time.

But that is finally changing. The shift has come after recent TV reports have depicted child miners like Daniel and Lukasa, digging for cobalt under tough conditions. “We have reached a tipping point where it’s become more expensive not to abide by good standards,” says Tyler Gillard, senior legal adviser to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, in Paris, who helped draft due-diligence guidelines for corporations on mineral supply chains. “Companies see this as a major threat to brand value,” he says. “Are consumers going to demand child-labor-free, corruption-free electric vehicles? I think it is coming.”

The prospect that bad publicity about child labor could provoke growing consumer anger toward the Congolese cobalt industry might explain why we faced suspicion and some outward hostility from DRC officials in reporting this story.

Despite obtaining media accreditation in advance from the central government in the national capital of Kinshasa, once photographer and filmmaker Sebastian Meyer and I arrived in Kolwezi, we had to seek permission from Lualaba’s provincial governor, Richard Muyej, to conduct interviews without being detained or ordered out of the country. Sitting in Muyej’s office, we listed sites we wanted to visit. In response, the governor told us several times, in French, “On a rien à cacher”—we have nothing to hide.

But our experience during one week in Kolwezi suggested a very different picture. The provincial Ministry of Mines and the police refused us entry into all but one mine site, telling us that we were forbidden to do any independent reporting without their permission. Some of our interviews were conducted under surveillance by police.

At the only cobalt mine to which we were granted official access—Kasulo, owned by the government—provincial mining officials rushed us around the site under the escort of armed police, telling us that the security presence was to protect us from harassment by miners. They refused our request to return to Kasulo a second time, despite the fact that we had an appointment there with Pact, the Washington, D.C.–based NGO working in Kasulo, with government approval, to end child labor in the mines.

On our last morning in the country, I asked Governor Muyej why his police and local officials had blocked us at virtually every turn. “People come with prejudices,” he said, citing journalists who have recently described child cobalt miners in Kolwezi. “They see all the bad, not the good.”

Since Amnesty's damning report in 2016, the government has indeed made attempts to clean up cobalt production—a task that is dauntingly difficult, if not paradoxical, given that top officials have benefited for years from opaque mining deals.

As an example of its new efforts, Lualaba’s mining authorities point to its “model mine” of Kasulo. The sprawling 420-acre site sits north of Kolwezi and began in 2012, when locals living on the land struck reserves containing cobalt with an extraordinary 14% mineral concentration; thousands of people poured in, sparking a free-for-all hunt for cobalt.

In response to the human-rights outcry, the provincial authorities last year fenced off Kasulo, creating a single entrance and exit to the site, at which it posted armed security guards. Next to the entrance are now hand-painted signs proclaiming in French and Swahili that children under 18 and pregnant women are banned from entering, as is anyone with alcohol.

Now, about 14,000 diggers converge on Kasulo every day to find cobalt, organizing themselves into small teams, then dividing their day’s earnings at sundown. The mine accounts for one-quarter of the cobalt from the DRC’s artisanal mines, and the exclusive rights to the ore are held by China’s Congo Dongfang International Mining, or CDM, a wholly owned subsidiary of Huayou Cobalt, which Amnesty’s 2016 report assailed for purchasing artisanal cobalt with little knowledge of labor conditions; Huayou says it has since implemented programs for Kasulo’s miners, run by Pact, to teach safety and explain why children should not mine. It remains unclear how people’s ages or pregnancy status are checked. “Do you see any child? No, none,” says Erick Tshisola Kahilu, director general of the province’s Ministry of Mines, standing amid hundreds of miners digging in the ground, as he guides us around the site. “And no babies either.”

Three months before I landed in Kolwezi, I had listened to DRC mining officials espouse their efforts in Kasulo, at a conference on mineral supply chains in Paris, hosted by the OECD. Congolese officials distributed a glossy 10-page brochure, proclaiming Kasulo as a “merveille émergente,” or emerging wonder. But the wonder inside Kasulo’s gates more closely resembles a frenzied scene from the California gold rush of the 1850s, rather than a current-day mining enterprise. Several hundred men chip away in deep holes and open pits without overalls, helmets, or any other protective gear, using basic hand tools like lengths of rebar to hack away at the surface, and hauling up rocks with handmade lengths of rope.

Around 4 p.m., the men load sacks of cobalt atop rickety bicycles or motorbikes, and roll them downhill to CDM traders, who stand ready to weigh the day’s output in an open-air hangar inside the gates of Kasulo. The buyers check the cobalt concentration of the rocks, which determines the price they will pay, using a small digital instrument called a Metorex. The prices are marked on handwritten lists tacked to the walls of the hangar. Inside caged areas, Chinese traders pass wads of Congolese francs to weary miners. Despite the digital measurements, several miners told us they suspected that the buyers routinely lowered the cobalt concentration figures in order to decrease the pay. There is no proof their suspicions are correct. But the free-for-all atmosphere seems primed for conflict. As the digging day in Kasulo ended, I witnessed a fierce argument among six miners standing on one rutted path amid the pits over how to split the day’s proceeds. The group’s total sum: 60,000 francs, or just $37.

For thousands of diggers working outside the more formal structure of Kasulo, the main trading hub is Musompo cobalt market, a cluster of about 50 open-air depots stretching a half-mile or so along the main east-west road out of Kolwezi. Musompo looks like the kind of village market that typically sells food or housewares. But for many tons of cobalt, this is a key gateway to the huge export market. Chinese middlemen, who speak rudimentary Swahili, test the concentration of cobalt brought in by diggers, and for about eight hours each day conduct a brisk trade in the metal. “I arrived recently from Nigeria,” says Xu Bin Liu, 30, from Hebei province, China, who runs the “Boss Liu” depot on the edge of the Musompo market. Seated at a small wooden table knocked together with nails and covered in burlap, Xu says the job involves tough haggling over prices.

Officially, Huayou’s CDM no longer buys cobalt from the Musompo market. But when we asked a Chinese buyer in Musompo for an interview, he said he needed the approval of his “boss,” a CDM official in Kolwezi. Tech companies like Apple, Samsung, and others have said that it is exceedingly difficult to prove that Musompo’s cobalt is free of child labor, and that the battery manufacturers that supply them—largely in South Korea and China—source the metal from child-labor-free mines.

The situation has prompted companies to make some tough choices: cut all artisanal miners out of their supply chain, for example, or halt purchases of DRC cobalt—either option potentially an economic disaster for the country. “If everybody simply runs, that can put children and families in a more vulnerable position,” says Ben Katz of the NGO Pact. “That is not reducing harm. It’s causing more harm.”

Among companies, a race is underway to decrease the cobalt in electric-vehicle batteries, from the current 10% or so to 5% or less. Under current technology, cobalt is essential in making high-performing batteries. But Tesla CEO Elon Musk has said he intends to produce non-cobalt batteries for the next generation of Tesla vehicles. Likewise, Volkswagen has partnered with QuantumScape, a startup in San Jose, to invent a cobalt-free, solidstate battery to replace the lithium-ion version—but they do not expect quick results. “We are at a very early research stage,” VW’s research director Axel Heinrich says. “I cannot tell you which year we will have batteries with no cobalt.”

Shaken by the possibility that children might be mining cobalt used in iPads and iPhones, Apple says that it has identified every smelter providing cobalt in its supply chain, and that they are regularly audited by independent third parties. Last year, the company announced that it would stop sourcing all cobalt from informal mines in the DRC, but that it did not agree with those pushing to pull out of Congo altogether. “There are real challenges with artisanal mining of cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” the company said in an email to Fortune. “But we believe deeply that walking away would do nothing to improve conditions for people or the environment.”

In an effort to lessen their dependence on the DRC, some companies are instead investing to develop new cobalt reserves; exploration projects are underway in Australia, Papua New Guinea, Canada, and Montana and Idaho in the U.S. That is partly because of rising anxiety that China is locking up most of the world’s cobalt supplies; in March, Glencore agreed to dedicate one-third of its entire cobalt production during the next three years to GEM, the Shenzhen-based battery recycling company. China produces a whopping 80% of the world’s cobalt sulfate—the compound used in lithium-ion batteries. And by 2020, China will likely produce 56% of those batteries, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence in London.

Yet leaving the DRC entirely is hard to manage so long as cobalt demand keeps soaring. Cobalt-free batteries are likely years away from mass production, and new mines outside Congo could take years to come on line. “The DRC is absolutely critical to the production of lithium-ion batteries,” says Caspar Rawles, Benchmark’s analyst on battery technology. “Without the DRC, we are not going to have enough cobalt. There is no question about that.”

North of Kolwezi is the tiny village known as UCK (pronounced “oo-say-kah” for the French acronym of its original copper mine). There, amid the dirt paths where children kick battered soccer balls, is one sign of how Silicon Valley is trying to grapple with child labor without alienating consumers.

In the backyard of a small house down a side lane in the village one morning in July, three teenage boys were bent over a van, learning how to repair it. They were participants in an Apple-funded program that began late last year, operated by Pact with the approval of Congolese authorities. The idea is to switch children from mining to new moneymaking skills. Today, about 100 teenagers are being taught sewing, cell phone repair, hairdressing, carpentry, catering, and other skills in villages around Kolwezi.

Not all families have welcomed Apple’s efforts, however. Some fear they will lose the income they desperately need to survive. “My parents asked me why I would abandon the mine,” says Thomas Muyamba, a soft-spoken 16-year-old helping to fix the vehicle in UCK village. He says he began digging for cobalt at age 12, and earned between $3.50 and $9 a day—crucial support for his family. Attending school is not an option, he says, since his family cannot afford school fees. So he convinced his mother that being an auto mechanic would ultimately serve the family best. “I tell them it will guarantee my future,” he says.

The family has the same hope for Thomas’s sister Rachel, 15, whose bushy pigtails frame her round cheeks like antennae. Rachel is one of about 10 girls who, until joining an Apple-funded project a few months ago, washed cobalt in the tailings in the river in Kolwezi—low-paid work that NGOs believe is particularly toxic for young lungs. Now, as part of the training program, the girls are seated at Singer sewing machines in a shed about five miles from Kolwezi, taking orders for clothes from clients and working on commission.

But the Apple program is not the only one trying to root out labor abuses in cobalt mining. Last year, China’s Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters launched the Responsible Cobalt Initiative, bringing together companies that agree to follow the OECD’s due-diligence rules by trying to eliminate child labor from their supply chains. The group includes Apple, Samsung SDI, HP, and Sony. In a separate program, Huayou and other refiners, miners, and carmakers have joined the Better Cobalt project, launched in March by RCS Global, a London-based organization that tracks and audits supply chains of natural resources. The group claims it will be able to identify cobalt that meets “the highest global standards,” focusing on child labor and human rights abuses. And the large commodities trader Trafigura has begun registering some 12,000 artisanal cobalt miners at the large Chemaf mine in Kolwezi, implementing health and safety standards and organizing them into cooperatives. Trafigura claims miners are earning dramatically more money as a result.

Besides the threat of a consumer backlash, companies also increasingly worry about potential legal liabilities, perhaps from an investor lawsuit, should they violate human rights. In July, the London Metal Exchange said that starting in January it would require every company that sources more than a quarter of its metals from Congo’s artisanal mines to be audited independently. Those that fail to meet human-rights standards risk being banned from trading on the LME. And in April, an informal WhatsApp group began among major investors, to share information with locals about abuses in the DRC’s cobalt industry. “If there are violations and there are lawsuits on a local level, the claims can be brought back to an international level, to a company traded on London Stock Exchange,” says Christine Chow, director of Hermes Investment Management in London. “I do not want to use a phone that has been put together by a 4-year-old.”

For all the efforts of companies and investors, the projects nonetheless have strong limitations—so long as grinding poverty persists for millions of Congolese.

That much is clear when you travel just a few miles away from the digging sites in Kolwezi. The day after meeting the teenagers Thomas and Rachel Muyamba, we meet them again, by happenstance, in their home village. (Again, Fortune has not named the community, for fear authorities might target those children in the village still mining cobalt for talking to journalists without permission.)

Sitting outside the tiny, mud-brick dwelling where Thomas and Rachel live with their family, it is clear that their mother and grandfather’s decision to allow them to join Apple’s training programs, and stop mining cobalt, has been difficult. The teenagers still earn just a fraction of what they made in the mines, putting a squeeze on the family.

As a crowd gathers around us while we talk, I ask which children are still digging for cobalt. Several hands shoot up—including that of 15-year-old Lukasa, the boy whose 12-hour day begins at 5 a.m. in this village.

For these child miners, the daily task of digging for cobalt still seems worth the backbreaking work—despite the growing number of business-backed programs urging them to quit. Lukasa’s earnings—$9 on good days—are far higher than Thomas’s pay from his Apple-funded job as a trainee auto mechanic, and match what Rachel makes for an entire week of sewing. Rachel says she expects to earn a solid living as a seamstress after a few years. “I will have my own shop,” she says.

If Rachel succeeds in her plans, it will be a rare chance indeed for one of Congo’s child miners to rise above the bare-bones survival gleaned from cobalt. Tech and auto companies are hoping thousands of other children find their way out of the mines too—allowing the technology industry to ward off consumer anger even as it continues tapping Congo’s giant wealth to give us the batteries we demand.

Education Resource

Meet the Journalists: Vivienne Walt and Sebastian Meyer

Cobalt is a vital mineral needed for the production of rechargeable batteries. Two thirds of the...