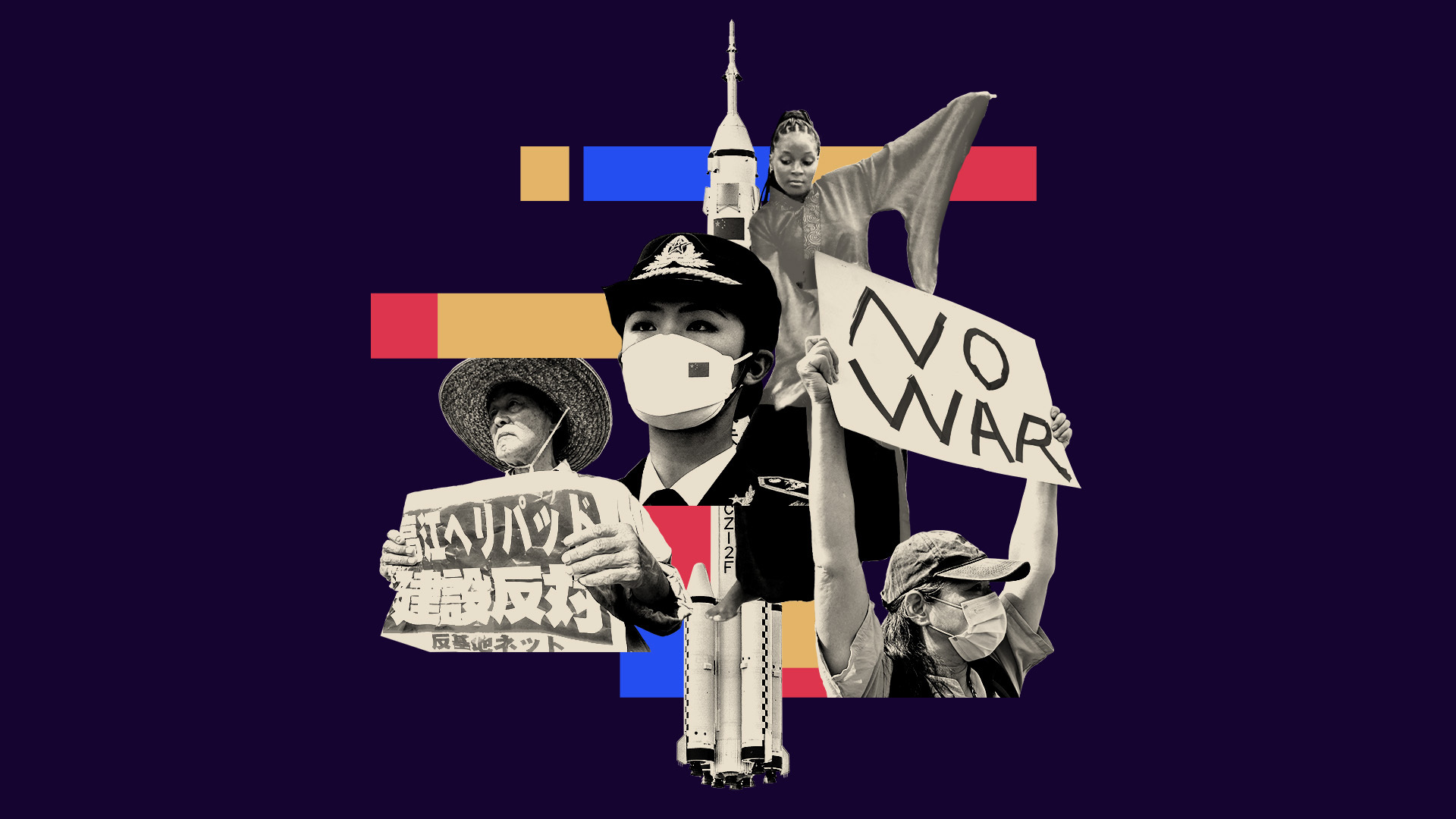

Okinawans fear a war between superpowers over Taiwan will bring devastation again.

OKINAWA, Japan — The Japanese island of Okinawa is caught in the crosshairs of geopolitical tensions many residents want no part of. The U.S. sees the island as imperative to its defense strategy in the Pacific, while China is increasingly flaunting its connection to the archipelago.

Why it matters: Okinawa — situated roughly halfway between China and Japan and just over an hour’s flight from Taiwan — could serve as a U.S. staging ground in a future conflict with China and play a crucial role in the defense of Taiwan.

Beijing views the U.S. military presence on Okinawa as an enormous security risk that also hinders the Chinese navy’s ambitions to operate far beyond its territorial waters.

China sent an aircraft carrier fleet between two islands in Okinawa prefecture late last year, the latest of several such operations in recent years. Chinese officials and state media in recent weeks have highlighted the island’s close historical ties to Chinese civilization, echoing the claims of Okinawa’s small independence movement.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

The U.S. has dozens of military facilities across the prefecture. Despite repeated calls from Okinawans to close the bases, the large U.S military footprint remains.

For many Okinawans, the U.S.-China tensions have raised fears that they will again be part of a conflict they don't want.

During World War II, “Okinawa was bullied and crushed between two powers,” says Yoshio Yonamine, a 69-year-old anti-base activist and Okinawa resident. He worries that “again Okinawa will be the front line in a battle between superpowers.”

What's Happening: China looks to Okinawa

After a decade of reticence, Beijing is once again talking about Okinawa. Chinese President Xi Jinping last month highlighted for the first time since taking office the historical ties between Okinawa and China. His remarks were featured in an article on the front page of the Chinese Communist Party’s main newspaper, the People’s Daily, which also reiterated China’s territorial claim to the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands. The rhetoric has fueled speculation that China is sending a message to Japan to stay out of the Taiwan conflict and that Beijing is trying to drive a wedge between Okinawa and Tokyo by echoing a small but vocal Okinawan independence movement.

The Chinese foreign ministry and Chinese embassies in Washington and Tokyo did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

Today, Okinawa is home to roughly 1.3 million people. It was once an independent kingdom known as Ryukyu, and many Okinawans consider themselves to be ethnically distinct from the Japanese.

“We are not Japanese. We are not American. I am native Ryukyu,” says Eiichi Miyanaga, who goes by the name Chibi and is a member of Koza BC Band, a pro-Okinawa independence rock band. The son of a native Okinawan woman and an American serviceman, Chibi, 72, writes songs about the archipelago’s history and sings in native Okinawan, an endangered language.

Chibi told Axios the beginning of Okinawans’ troubles trace back to 1609, when a Japanese clan first invaded the island. In the 19th century, the Japanese empire took formal control of the archipelago, repressing native Okinawan language and culture and eventually forcing residents into a war of empires. In one of Chibi’s most popular songs, he calls on Okinawans to “wake up” and “open up your eyes.”

More than 400 years later, the Chinese government and Chinese government officials are amplifying the independence movement’s message about the history of Okinawa, which under the Ryukyu Kingdom was a tributary state to Beijing. The movement also suggests Okinawa’s sovereignty may not belong to Japan.

The cultural ties between Okinawa and China don’t necessarily translate to an affinity for Beijing, however. “I don’t need any support from any big power,” Yonamine, the activist who opposes the U.S. military’s presence on the island, told Axios. Yonamine expressed fear that "if China supports us, they will annex us."

Between the Lines: High stakes in the Indo-Pacific

China is seeking to establish diplomatic, military and economic dominance in the Indo-Pacific, often eroding international legal and democratic norms in its wake. The U.S. has responded by boosting its own presence in the region and, together with Japan and Taiwan, emphasizing the importance of preserving a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” The Biden administration has also enshrined the promotion of democracy over authoritarianism as the driving force of its foreign policy.

But the U.S.’ public commitment to those ideals is pitted against the popular demands of Okinawans, who have protested against American military presence nearly every year since the U.S. ended its formal occupation of the island and returned it to Japanese sovereignty in 1972.

The U.S. is reluctant to leave the island in part because Okinawa’s location would play a strategic role in a conflict between the U.S. and China over Taiwan.

But Okinawans generally oppose the bases being on the island.

More than 15% of the land on Okinawa’s main island is used by the U.S. military. The Okinawa prefecture comprises less than 1% of Japan’s land area but hosts more than 70% of U.S. military facilities in Japan.

A June poll found 70% of Okinawa residents believe the concentration of U.S. military facilities on Okinawa is “unfair.” An even higher number, 83%, believe the U.S. bases would become “targets of an attack in an emergency.”

Voters have passed anti-U.S. base referenda, which are largely symbolic but still put pressure on the local and central governments to heed popular opinion. The Okinawa Times, one of two main newspapers on the island, has adopted an anti-base position as its editorial stance. In addition to annual protests, spontaneous demonstrations — around incidents such as the 2016 rape and murder of an Okinawan woman by a U.S. Army base worker — have drawn tens of thousands of protestors. Other grievances about the bases include U.S. repression during the years of occupation, environmental degradation, chemical spills, noise pollution and helicopter crashes.

“Okinawa is occupied by U.S. military bases,” Zenfuku Ikehara, 88, told Axios on the sidelines of this year’s protest in May, when hundreds of protesters marched near Kadena Air base, one of more than 30 U.S. military facilities in the prefecture that together host approximately 25,000 active-duty U.S. military personnel.

“There are so many problems from the U.S. bases. It’s unfair, why do we have to carry such a burden?” he said.

Ikehara was 11 years old when the 82-day Battle of Okinawa began in 1945. An estimated 100,000 Japanese soldiers, 12,000 U.S. troops and up to 150,000 Okinawa civilians — nearly one-third of the island’s civilian population at the time — were killed in what was the bloodiest fighting in the Pacific during World War II. Ikehara survived the battle by hiding in a cave. After U.S. forces defeated the Japanese troops, he and other civilian survivors were put into camps where there was little food, while the U.S. military swiftly seized land to construct runways and other military facilities.

Memories of the battle and the years of struggle that followed brought Ikehara out to the march, where he supported protesters from his driveway.

That kind of suffering is indescribable. I want people to remember my experience, the suffering that I bore.

Zenfuku Ikehara, 88

Despite the repeated demands of the island’s residents, the U.S. State Department told Axios the “troop presence in Okinawa is fundamental to our treaty commitment to the defense of Japan. U.S. service members are on Okinawa, a strategically important location, to provide the forward presence needed to maintain deterrence, help ensure the defense of Japan, and preserve peace, security, and economic prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.”

When asked about the tension between local opposition to the bases and the Biden administration’s emphasis on democracy as a justification for the growing U.S. role in the Indo-Pacific, U.S. Marine Corps Col. Matthew Tracy of the Okinawa-based III Marine Expeditionary Force didn’t answer directly but called it a “fundamentally political question” that U.S. policymakers, rather than military personnel, must decide.

What to Watch: Okinawa’s diplomacy push

Okinawa’s governor is navigating growing geopolitical tensions surrounding the prefecture. In the past six months, Denny Tamaki has visited both Washington and Beijing.

His big message to the U.S.: Reduce the American military presence.

And to China: Let’s “continue our mutually beneficial relationship.”

Okinawans want to avoid conflict in the Taiwan Strait because it could affect them too, Tamaki told Axios. “In the Second World War, Okinawa suffered huge damage, so it is our understanding that this kind of atrocity must never happen again.”

To try to guarantee that, Tamaki is taking on the role of diplomat.

[Okinawans] firmly believe that we must avoid a situation in which issues over the Taiwan Strait get out of hand and lead to unpredictable circumstances.

Governor Denny Tamaki

Tamaki told Axios that Okinawa can “contribute to the easing of tensions” by pursuing peaceful ties with China. Under his leadership, the Okinawa prefectural government is opening a regional diplomacy office, which he has said is aimed at focusing on cultural and economic exchange between the island and China.

During a visit to Beijing in early July, Tamaki visited the centuries-old graves of Ryukyuans who had lived in China when Okinawa was the independent Ryukyu Kingdom. "We will inherit and firmly maintain ties between China and Okinawa and create a peaceful and rich era,” he said, per Kyodo News.

Some commentators in Japan have criticized Tamaki’s actions, saying he runs the risk of contradicting and muddying the foreign policies of the central government in Tokyo, which is firmly aligned with Washington.

Tamaki reportedly told a local Okinawan newspaper last month that "rather than looking to the government [in Tokyo] as our counterpart, it would be better to raise the issue with the rest of the world, so that a wider range of counterparts will appear."

As Tamaki charts a course through rising U.S.-China tensions, one thing is clear: Okinawans don't want to be caught up in someone else's conflict again.