Thousands of acres of salt marshes that buffer the South Atlantic coast from hurricanes, sustain the seafood industry and bolster the tourism economy are in danger of washing away, cthat have made the threat of sea level rise more menacing.

State regulators in the Carolinas and Georgia have issued at least 28,000 permits during the past three decades to build, expand, replace or repair docks, bulkheads, piers and other structures in tidelands that hug the coast, a McClatchy investigation has found.

In some cases, developers transformed unspoiled coastal areas into exclusive high-end communities, with long docks running hundreds of feet through salt marshes. In others, property owners added to the glut of existing buildings, docks and bulkheads already lining some of the region’s most visible salt marshes.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Federal data obtained by McClatchy show a 22% increase in developed land within one-half mile of salt marshes in the three-state region since 1996. For areas within 300 feet of marshes, the rate of development increased by 18%, according to data analyzed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Map: How many permits have been issued?

Coastal regulators, restrained by laws that make development easy, often approved work in tidelands with limited review, McClatchy’s investigation found.

Those efforts occurred as local governments welcomed expansive new development along the states’ tidelands, putting more pressure on state government agencies to process permits.

And amid the growth, sea levels rose at increasing rates.

Sea levels have increased along much of the Carolina-Georgia coast by about 3 millimeters per year, on average, in the past century, say scientists at NOAA’s Charleston office,

But in the past 30 years, sea levels have increased to nearly 5 millimeters per year on average. In the past decade, the rise has approached 15 millimeters annually, with the rate projected to continue to rise, NOAA researchers say.

“A lot of people enjoy the fact that they live around these wetlands and they can go out into those areas and fish and whatever else they want to do,’’ said Nate Herold, a scientist with NOAA’s Office of Coastal Management in Charleston. “But a lot of those wetlands are not going to be the same as they are now, if they even still exist in the future.’’

Increased development, eroding land and rising seas are a lethal combination for salt marshes because they need room to spread into other areas as the higher water pushes them that way.

The slow expansion of tidelands across the landscape is part of a natural phenomenon that has allowed sediment-starved marshes to survive for thousands of years as sea levels rose.

Unlike thousands of years ago, however, bulkheads, buildings and other structures block the movement of many marshes, putting the wetlands at increased risk of being squeezed out by rising seas.

Savannas of grass in developed areas will become mud flats or open water if seas continue to rise as expected and increasingly erode the marshes, say some scientists who study salt wetlands in the Southeast. Sediment-depleted salt marshes will grow skinnier and the grasses will eventually die, they contend.

Bulkheads — hard walls built to protect marsh-side property from erosion — are particularly threatening to the survival of salt marshes.

“If a bulkhead is in front of a marsh, it probably is doomed,’’ said Carolyn Currin, a long-time NOAA researcher who retired in 2021 from the agency’s Beaufort, NC, lab. “It will just drown over time.’’

On one popular part of North Carolina’s southern Outer Banks, areas hemmed in by bulkheads suffered three times more marsh loss than areas without bulkheads, Currin said, referring to a 2018 report by a Duke University graduate student she worked with.

The study by Samantha Burdick found that 85 of 89 spots with bulkheads in the area of Bogue, Back and Core sounds experienced a loss of marsh from the early 1980s to 2013. The research, now being peer-reviewed, was conducted in Carteret County. Burdick and Currin have submitted the paper to a scientific journal for publication.

“Predicted increases in the rate of sea level rise will likely exacerbate marsh loss, as increasing water levels drive erosion of the marsh edge and reduce the ability to accrete marsh,’’ Burdick’s study said.

North Carolina regulators in 2012 identified a total of 815 miles of “armored’’ shoreline, areas with devices built to keep water from encroaching onto the land. Today, that number has grown to 1,100 miles, according to research cited by the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality in a report earlier this year.

Bulkheads were among the main reasons wetlands were damaged in North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties, the 2021 N.C. Department of Environmental Quality habitat protection plan says.

Of at least 28,000 permits approved for development in Carolinas and Georgia tidelands over the past three decades, most were for small projects that individually have minor impacts but, collectively, can hurt salt marshes.

About 5,000 were for bulkheads, approximately 3,300 of them in North Carolina, according to records obtained by McClatchy. But the overall amount of bulkheads, and docks in salt marshes, is likely far higher because North Carolina only provided data since 2009.

And regulators in South Carolina, where more than 17,000 permits have been approved for development in tidelands, did not provide detailed permit data showing how many of those were for bulkheads.

Graphic: SC Permits for Salt Marsh Developments

The state did release a single Georgia Southern University study that found about 1,000 bulkheads and nearly 13,000 docks. Overall, the study found 17,775 man-made structures in tidal areas.

Georgia has as many as 685 approved bulkheads, according to state records.

A 2015 study by researchers at the University of North Carolina found that about 14% of the nation’s coast is armored with bulkheads, seawalls and other structures to protect coastal property along beaches and marshes. That’s expected to increase, particularly along the Gulf of Mexico and the South Atlantic, where more than half of the country’s tidal salt marshes are located.

How able South Atlantic salt marshes will be to survive sea level rise is a point of some scientific debate. Some researchers say the marshes — notably big ones in South Carolina and Georgia — have a fighting chance.

Those being overwhelmed by sea level rise that have room to move will shift positions, meaning the net amount of marshland could remain the same or even increase.

Or some marshes could keep pace with sea level rise if they have enough sediment in nearby waterways to build up.

One way salt marshes have overcome sea level rise in the past is by trapping large amounts of sediment flowing through the water and depositing it on the marsh bottom, thus building it up.

Still, the future of the region’s developed marshes is a substantial concern. If sea level rise outpaces a marsh’s ability to build up naturally — and there’s no room for the tideland to move — the marsh disappears.

The South Atlantic's Sea of Grass

The South Atlantic coast has some of the most extensive salt marsh systems in the country. The marshes cover about 1 million acres from North Carolina's Outer Banks to North Florida. Areas in pink on this map show approximate locations of salt marshes. Source: NOAA

Map by Neil Nakahodo/The Kansas City Star

Drowning marshes loom near Wilmington, Charleston

Developed marshes most at risk of being lost to sea level rise are near Wilmington, N.C., and along the southern North Carolina coast; nearby North Myrtle Beach, S.C.; Murrells Inlet, Pawleys Island and Charleston, S.C.; and around Jacksonville, Fla., according to federal maps of salt marsh resilience.

In addition, forecasts have raised concerns about Savannah and Tybee Island in Georgia, as well as Hilton Head Island, S.C., the maps show.

The bottom line is that while some undeveloped marshes will shift inland, the developed marshes people are most familiar with are in danger, NOAA’s Herold said.

Overall, if the South Atlantic region experiences a 4-foot rise in sea levels by the end of the century, as projected under mid-range sea level rise scenarios, research Herold conducted indicates problems for developed and undeveloped salt marshes people are familiar with. His findings:

- North Carolina could lose up to 34% of its existing salt marshes by 2060 and 73% by 2100.

- South Carolina could lose up to 23% of its existing salt marshes by 2060 and 46% by 2100.

- Georgia could lose up to 14% of its existing salt marshes by 2060 and up to 25% by 2100.

Herold based those projections on tide gauge data and generally accepted intermediate scenarios for sea-level rise. To be conservative, he figured that salt marshes would build up by 6 millimeters annually. Should marshes build up at levels higher than 6 millimeters each year, less of the tidelands would be lost, he said.

Sea level rise threatens salt marshes South Atlantic

Salt marshes most threatened by rising sea levels are on the southern North Carolina coast, the Murrells Inlet and Charleston areas of South Carolina, and Jacksonville, Fla., according to resiliency maps from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Threats also exist in the Hilton Head Island-Savannah area. Areas in red and orange on this map show spots where marshes are least resilient to sea level rise. Areas in green are most resilient. Source: NOAA

Map by Neil Nakahodo/The Kansas City Star

According to records released by the Department of Health and Environmental Control, South Carolina has issued 17,104 permits for development in tidelands and marshes since 1990, or about 80% of all permits for construction in salt water in the Palmetto State.

Records show that Charleston County leads South Carolina in the number of permits granted for development in tidelands.

Since 1990, DHEC has granted at least 8,776 permits for docks, bulkheads and other structures in Charleston area tidelands, according to records provided by the agency and analyzed by McClatchy. Property owners in Beaufort County, S.C., home to Hilton Head Island, received 4,737 permits, second only to Charleston.

Georgia regulators have issued 7,218 permits since the early 90s, according to data provided by the state’s Department of Natural Resources.

State officials in Georgia say permits in the agency’s database may include some approvals for structures that were never built. The state has independently counted about 6,200 structures along marshes and beaches, officials told McClatchy.

The highest number of permits in the Georgia state database — 2,808 — were for projects in Chatham County, home to Savannah and Tybee Island. The second highest numbers — 1,302 — were in Glynn County, where Jekyll Island and St. Simon’s Island are located.

North Carolina regulators have issued about 3,300 permits for bulkheads in tidelands away from the oceanfront beaches since 2009. The state said it could not provide permit data before 2009 and it did not provide data showing the number of dock permits.

Of the bulkhead data provided by North Carolina, nearly two-thirds of the 3,300 permits were issued in four counties: Dare, Brunswick, Currituck and Beaufort.

Dare County had the most bulkhead permits since 2009 with 801. It is home to some of the most popular areas of the Outer Banks, including Duck and Nags Head.

Brunswick had the second-most bulkhead permits since 2009 with 450. It is a rapidly developing area south of Wilmington that includes a string of small beach towns in front of marshes, such as Sunset Beach and Holden Beach.

Megan Desrosiers, president and chief executive at the Georgia conservation group One Hundred Miles, said regulators should be more careful about approving development in and around salt marshes. But they are sometimes put in bad positions, she said.

The pressure on salt marshes is caused by a failure of local governments to better control development on high ground, just beyond state jurisdiction, she said.

People who buy homes and develop property on high ground next to marshes often seek dock and bulkhead permits from state regulators to enhance and protect their land, she said.

“It totally falls on the lack of restrictive zoning — and on the people who grant variances when there is restrictive zoning,’’ said Desrosiers, who also is familiar with South Carolina environmental issues as a former official with the Coastal Conservation League in Charleston.

“I put the burden on local governments,’’ she said. “That’s where the houses get approved. Then people go straight to DNR and they ask for their dock or they ask for their bulkhead.’’

She and others say salt marshes can be better protected with better local government restrictions on development and strong setbacks from marshes. The use of natural materials to buffer marsh-side property from rising seas also would be better than hard bulkheads, some say.

Seafood and hurricanes

Mark Marhefka is a commercial fisherman and seafood dealer who is worried about an array of issues that affect salt marshes, including sea level rise and the increasing development he’s seeing around the tidelands where he works.

“All the building they are doing and the amount of people that move into the area are helpful to our business, but it’s also hurtful to the environment,’’ he said.

Marhefka said salt marshes are important to maintain the species that grow into the fish he catches and sells, including grouper. But he’s not seeing as many of the young grouper that were in the marshes years ago.

Pollution, rising ocean temperatures and, in some cases, overfishing are having an impact, he suspects. Now, sea level rise is something to worry about.

“It all works hand in hand,’’ said Marhefka, who has been active in fisheries management issues in the Charleston area for years. “If all the smaller fish aren’t there, then neither are there going to be the bigger fish for us offshore.’’

Vanishing marshes

This graphic uses NOAA images of the Southeastern coast to show how sea level rise will impact salt marsh systems.The larger image will show the marsh system, in magenta, gradually being submerged under water as the sea level rises nearly four feet by 2100.

Overall, the commercial fishing industry that Marhefka works in provided a collective economic impact of $1.5 billion in sales in east Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina in 2017, according to NOAA.

The productivity of salt marshes bolsters the seafood business by not only providing a place for small fish and crabs to grow up, but their banks have historically been popular places for restaurants that attract tourists.

Those places include Calabash, N.C., Murrells Inlet, S.C., Brunswick, Ga., and Mount Pleasant, S.C.

Salt marshes that lie behind the beaches of the Carolinas and Georgia are more broadly part of a tourism economy that provides billions of dollars in revenue for the three states.

Perhaps more important than anything, studies show that salt marshes protect people and property when big storms hit.

A 2021 study found that coastal wetlands, including salt marshes, save more than 4,600 lives around the world each year and provide some $447 billion in storm protection.

“Coastal wetlands reduce the damaging effects of tropical cyclones on coastal communities by absorbing storm energy in ways that neither solid land nor open water can,’’ according to the study, published this summer.

Forest becomes giant marsh-side neighborhood

To get an idea of how much development has occurred in salt marshes and tidal areas as seas rose, look at Charleston County, the historic South Carolina community where people are increasingly settling each year.

Growth is inching into areas once thought to be unsuitable for new homes and businesses — and that includes salt marshes.

The Mount Pleasant area just up the coast from Charleston is a prime example, said coastal geologist Rob Young, who runs the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University.

“The development on that marsh edge moving up (U.S.) 17 toward Georgetown from Mount Pleasant makes you want to vomit,’’ Young said. “They are just developing the hell out of that shoreline with these subdivisions.’’

Similar patterns are occurring west of Mount Pleasant off S.C. 41, a one-time rural road that today has become a major development corridor.

In little more than 30 years, developers turned one forested area along the Wando River into the upscale Dunes West community.

Thousands of homes can be found there, many of them million-dollar structures. Many are owned by doctors, ex-college and professional athletes, business people and retired industrial executives.

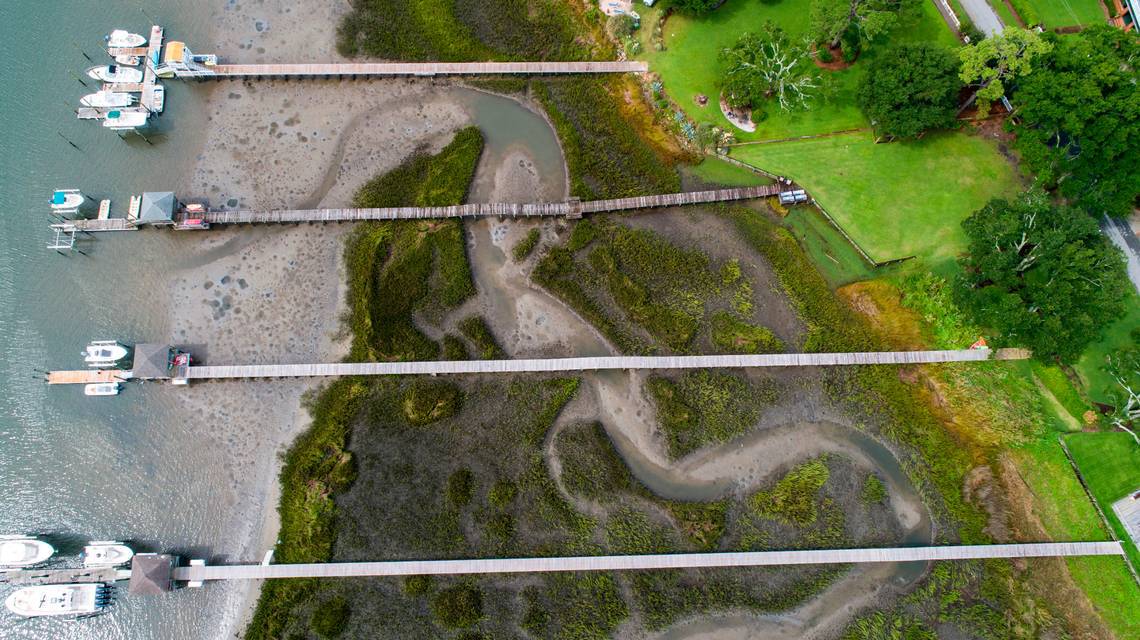

Extending from the houses are docks that run through the marshes along the river near the Charleston-Berkeley county line.

Dunes West is among several high-end developments OK’d by the town of Mount Pleasant, where growth has exploded. The town at one point authorized more than 6,000 homes for Dunes West and Park West, a comparable project next to it, according to the Mount Pleasant planning department. (See a Mount Pleasant map here.)

The Dunes West agreement, approved in 1990, gave the developers flexibility to build a sprawling community without going by traditional zoning rules.

Since 1990, South Carolina state regulators have approved more than 350 construction permits in the marshes and tidal creeks surrounding Dunes West, state Department of Health and Environmental Control records show.

The agency said it could not provide a specific breakdown of what the permits were for, but many were for docks and bulkheads.

Charleston County property records reviewed by McClatchy show at least 200 docks run through the marshes from Dunes West homes to the Wando and tributaries that flow through the community.

The growth at Dunes West, which environmentalists say could block the movement of salt marshes as seas rise, preceded what has become a major area for development along the river’s salty wetlands. Disputes have erupted recently over plans to develop the nearby Cainhoy area.

Multiple efforts to reach a representative of Dunes West were unsuccessful, but one of the project’s early developers said he and his partners were not thinking about how sea level rise might impact salt marshes when Dunes West was designed.

Noel Thorn, part of a partnership involving the Georgia-Pacific paper company and the Wild Dunes company, said he would have designed the project differently if he was putting Dunes West together now. It likely would have smaller lots and more green space, he said.

He said he doubts a more modern design would have abandoned waterfront property, but it could have been improved upon.

“None of us thought about what we’re talking about today: climate change and sea level rise and planning and best land practices,’’ Thorn said, noting that the Dunes West effort involved “one of the worst land plans probably that could be. "

Bulkheads and other barriers

Chris DeScherer, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, said the steady drip of minor development, such as docks and bulkheads, can collectively cause an array of environmental problems, including blocking marshes from spreading onto open land as seas rise.

“All of those minor permits in the salt marsh, they add up, and they have a cumulative impact on our marsh ecosystem,’’ said DeScherer, whose organization is challenging permits in the Cainhoy area, across the Wando River from Dunes West.

When questioned about the project approvals, DHEC said it is bound by South Carolina law to OK docks and bulkheads if property owners meet the requirements.

The agency said it encourages the use of community docks for new development, but can’t force anyone to do that. If a property owner meets the state rules, he or she can get a permit, the agency said.

“The guiding documents and the department encourage community docks and joint use docks rather than multiple single use private docks,’’ the department said in an email to The State of Columbia, S.C., a McClatchy news outlet.

“However, the waterfront property owner decides what type of dock they would like to request. If the request is consistent with the statutory and regulatory standards, the department does not have the authority to deny or direct the waterfront property owner to apply for a different dock type.’’

DHEC said the agency could not address whether it had any concern about the impact of permitting docks for Dunes West without conducting research.

Developed marshes aplenty

Less than two hours up the South Carolina coast lies Murrells Inlet, a community of seafood restaurants where development has also reshaped the saltwater wetlands.

South Carolina regulators have approved more than 400 permits for development or redevelopment in the tidelands since the early 1990s, according to records obtained under the state’s open records law and analyzed by McClatchy.

That added to the already existing development that began to rise around the Murrells Inlet marsh in the 1950s and 1960s.

Restaurants at Murrells Inlet, known as the Seafood Capital of South Carolina, can generate more than $40 million in sales in a year, according to a 2013 report from Coastal Carolina University.

Today, researchers at NOAA in Charleston say Murrells Inlet and nearby Pawleys Island have some of the most imperiled salt marshes in South Carolina because of sea level rise, the smaller size of the marshes and the amount of development surrounding them.

The salt marsh at Murrells Inlet is about 3,000 acres, lying east of U.S. 17 Business across from Garden City, a beach community south of Myrtle Beach. (See a Murrells Inlet map here.)

Using Google Earth imagery, McClatchy also identified other marshes facing sea level rise that are surrounded by development in the Carolinas and Georgia. They include:

▪ St. Simons Island, Georgia. Aerial imagery shows an increase in development since 1993 along the marsh near Ledbetter Island, a hammock in the tideland behind St. Simons. Several spots in the area had no development in 1993, but are packed with houses today. Two salt marshes in the area south of Sea Island Road consist of about 1,900 acres.

▪ Tybee Island, Georgia. Aerial imagery shows extensive development along the marsh behind the popular beach resort near Savannah. Much of the development predates the early 1990s. The marsh is surrounded by houses and roads. All told, the salt marsh immediately behind Tybee, from U.S. 80 to Catalina Drive, is about 880 acres.

▪ Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina. The area north of Eastwood Road-Causeway Drive has developed steadily since the 1990s. Once forested areas on the mainland across from the northern stretch of Wrightsville Beach are now full of homes. The area north of Causeway Drive behind Wrightsville has about 1,100 acres of salt marsh between the beach and the mainland.

▪ Sunset Beach, North Carolina. The southern North Carolina beach community developed long before 1990, but has continued to see more dense growth in areas west of the Intracoastal Waterway. Several dozen homes and docks, for instance, were developed at one spot along the marsh from 1993 to 2021. The area contains more than 1,400 acres of marsh between Sunset Beach and Ocean Isle Beach.

▪ Folly Beach/James Island, South Carolina. Aerial imagery reviewed by The State newspaper shows extensive development since 1989 on the back of James Island and on several peninsulas along Folly Road that extend into the marsh. Drone footage taken by McClatchy shows a line of bulkheads on a small peninsula near the mainland at James Island. Tightly bunched houses line the peninsula that three decades ago was sparsely populated, aerial imagery shows. About 4,500 acres of salt marsh are in the immediate area on both sides of Folly Road, between Folly Beach and James Island.

▪ Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. Property along Marshland Road, which runs along the back of the Broad Creek area salt marsh, has been transformed into a more densely populated place since 1994. Multiple areas between the road and the marsh that were forested 25 years ago are today full of houses. Marshland Road has a popular marina and multiple gated communities and restaurants along the inner marsh. At one spot visited by a journalist with The State in June, construction workers were erecting dozens of new houses that were being marketed by an Atlanta real estate company. Hilton Head’s salt marsh consists of more than 1,400 acres between the Cross Island Parkway and Mathews Drive.

Routinely issued development permits

Have coastal regulators paid enough attention to development along salt marshes?

Not everyone is so sure.

Beach issues have taken a higher priority than concerns about salt marshes because the seashore was the initial magnet that attracted people to the coast. In short, building in tidelands receives less scrutiny, they say.

“It goes back to marshes not being as charismatic as beaches,” University of North Carolina marine scientist Michael Piehler said, noting that while North Carolina “has an overwhelmingly larger supply of inland shoreline, people don’t pay as much attention to it as they do the ocean shoreline.’’

North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia all review requests to build in salt marshes, but the states often spend less effort examining requests for what they consider minor permit activity, such as private docks.

Minor permits make up most of the permit approvals issued by the states, according to records provided by agencies and interviews with regulators.

In South Carolina, for instance, more than 15,000 of the more than 17,000 permits for docks, bulkheads and other work in tidelands were considered minor, according to DHEC records.

The federal government requires individual permits for people wanting to build major projects in wetlands, but sometimes grants blanket approvals for what it considers routine construction, such as building a private bulkhead, said Bill Sapp, a former U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lawyer who now works with the Southern Environmental Law Center in Atlanta.

That leaves states to decide if they want tougher rules.

Richard Chinnis, a former South Carolina coastal permitting chief, said it wasn’t difficult to get bulkhead permits in South Carolina during his time with DHEC.

Bulkheads remained legal in marshes and tidal areas, even after oceanfront seawalls were banned in 1988 because of concerns about their tendency to worsen beach erosion. Seawalls are similar to bulkheads.

“There were no kind of direct prohibitions in the ... marsh permitting for bulkheads,’’ said Chinnis, who worked at DHEC for parts of three decades. “They were routine permits.’’

DHEC discourages bulkheads in areas where enough marsh exists to protect high ground next to it, but Chinnis said he could not remember ever denying a bulkhead permit.

Bulkheads not only were legal to build in South Carolina marshes if the state granted permission, but property owners could construct homes or other structures close behind the walls.

How salt marshes survive

Many local governments have slowly adopted marsh-side setbacks in South Carolina, but it took years for that to happen. North Carolina has shoreline setbacks, although some have questioned whether they are adequate.

In addition to bulkheads, docks are a concern. While docks don’t directly block the movement of salt marshes, they indicate the amount of development behind them. And that development, including homes and bulkheads, can stand as obstructions as sea levels rise and the marsh moves their way.

A dock in a marsh can increase a home’s value by $200,000, Chinnis said developers have told him.

In one 1995 case over whether a property owner should be allowed to build a dock in Charleston County, Chinnis testified that his agency turned down only four to five dock permits annually out of several hundred applications it received. At the time, about 70% of the permits requested for development on the coast were for docks, he said.

During the hearing, Chinnis said, “The only basis for denying a dock permit to someone who has waterfront property is if the structure would block another property owner’s access to water,’’ according to an administrative law judge’s order granting a permit for the Charleston County landowner.

Georgia and North Carolina

In Georgia, the state has a tidelands protection law that many say has been instrumental in limiting unwise development on much of the coast.

The landmark 1970 law, approved in response to an effort to establish a phosphate mine in a beloved marsh, has had the effect of preventing bridges from being built to many barrier islands and hammocks - small woodland patches of land - in the marsh, state officials and conservationists in Georgia say.

Yet Georgia’s law, a source of pride to many who live by the coast, generally doesn’t apply to private docks and some other small-scale construction in tidelands. Individually, those types of construction projects aren’t a big deal but collectively can hurt salt marshes by surrounding them with development, critics say.

About 6,000 of the more than 7,200 permits Georgia officials have considered for development in tidal areas since 1990 have been for docks, according to data released by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and analyzed by McClatchy. About 1,200 more permits have been for “bank stabilization,’’ including about 685 for bulkheads, the data shows.

Many of those structures received authorization without the tougher level of review required by the Georgia tidelands law, which often deals with major projects, state officials acknowledge.

It can take up to six months to get a permit under the Georgia tidelands law, but as little as a month for projects not covered by it, according to the Georgia Coastal Resources Division. The tidelands law “is much more rigorous in terms of the amount of required information and justification that is reviewed by staff,’’ Georgia regulator Jill Andrews said in an email.

Often, property owners are covered by what are known as general permits, essentially blanket approvals if landowners fill out paperwork that asks basic questions, such as who owns the property.

An extensive 2012 master’s thesis by a University of Georgia student, which examined the marshland law, said Georgia’s coast has changed since 1970. But the study questioned whether the law needed improvement to match those changes.

It said “contemporary context and unanticipated circumstances continue to prompt questions about the ability of the (law) to deliver on the original intent." The thesis by Danyel Goldbarten Addes said the law has been criticized for “using vague, imprecise and therefore lenient guidelines.’’

Charles “Buck” Bennett, compliance and enforcement manager for the Georgia coastal division, said the law has flexibility built into it. Bennett also noted that his staff checks on even minor development projects for compliance.

Andrews, Georgia’s coastal management chief, said the state is bound by the law to approve permits when requests meet the standards.

Still, she said only a handful of areas on the Georgia coast are actually dealing with major development issues. The state contains vast areas that are protected as nature preserves.

“Two-thirds to three-quarters of our barrier islands are protected,’’ she said. “The big story in Georgia is conservation land and how many of these areas have been protected.’’

Like South Carolina, Georgia has about 350,000 acres of salt marsh, one of the highest amounts in the country.

Conservationist Desrosiers said that the protection, while a good thing for Georgia, has put more pressure to build in places like St. Simons Island and Tybee Island. Both of those resort areas have marshes surrounded by development and roads.

Low, mid and high tides by McClatchy on Sketchfab

In North Carolina, pressures to develop near salt marshes continue following years of state approvals for bulkhead construction, often without detailed reviews of plans.

Historically, most permits for bulkheads or riprap structures along a shoreline had been granted automatically via general permits. As opposed to permits for large-scale projects that often required detailed review from multiple government agencies, general permits allowed bulkheads to be built as long as they met certain basic conditions.

That means the approximately 3,300 bulkheads approved since 2009 have been built or repaired with a simple site visit.

For years, most bulkheads were actually easier to gain approval for in North Carolina than some projects that relied on materials that were less likely to erode or destroy marshes.

Those projects, known as living shorelines, are protection systems where breakwaters are built just below the high-tide line to let water come ashore at lower energy levels. Natural materials, such as oyster shells, are often relied on, as opposed to bulkheads that can increase marsh damage and erosion.

The state never considered bulkheads to be particularly harmful to the environment, Burdick said in the Duke University study.

“Policy regarding shoreline stabilization in North Carolina is based on the assumption that bulkheads do not significantly impact public trust resources, including salt marshes,’’ she wrote in the 2018 paper.

Recently, North Carolina shifted its coastal rules so that living shorelines could be approved more easily than in the past.

Low fines and politics

North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia have made scores of enforcement cases since the 1990s against people who illegally built docks, bulkheads or other structures in salt marshes.

It’s a responsibility coastal enforcement officials say they take seriously.

But in some cases, the laws — and enforcement efforts — haven’t been strong enough to deter people from breaking the rules.

In South Carolina, one former coastal regulator said low fines hurt efforts to stop illegal building in tidelands. Construction companies, at one point, considered paltry fines the cost of doing business, said the ex-regulator, who asked not to be identified because of the person’s current job.

“There was no respect from the dock builders for the permitting process and the enforcement process,’’ the ex-regulator said.

In South Carolina, anyone deemed guilty of a violation can be fined up to $5,000 for a first offense and/or imprisoned for up to six months. But the state law also says minor violations, which it defines as involving less than 225 square feet of tidelands, can carry penalties of $50 to $200.

Records released by the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control show about half of the fines for coastal violations have been $500 or less since the mid-1990s. Overall, DHEC has taken more than 400 enforcement actions during that time. The ex-regulator said DHEC has made improvements in recent years with its enforcement effort.

South Carolina has changed its enforcement policy, choosing to work with property owners found to be in violation of the law, rather than being quick to issue fines, state officials say.

Before the policy was put in place about nine years ago, DHEC was routinely issuing anywhere from 20 to more than 50 coastal enforcement orders each year, records show. After that, enforcement actions against people who violated tideland laws plummeted to fewer than 12 a year.

Elizabeth von Kolnitz, who runs DHEC’s coastal division, defended the agency policy.

“We find that people are much more willing to cooperate at that level, when it’s not this formal enforcement option,’’ she said. Von Kolnitz said the 2012 change in policy now allows coastal agency staff to provide “compliance assistance’’ to property owners suspected of violations, before sending a case to enforcement for a possible fine or other sanction.

Asked whether more enforcement cases would deter people from breaking coastal laws, Von Kolnitz said, “I don’t know that I have a comment specifically on that.’’

In North Carolina, the average number of coastal tideland enforcement cases has dropped in recent years when compared to the longer term, according to an Oct. 6 email from the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to The News & Observer.

Since 2009, the agency’s coastal management division has averaged 11 coastal wetlands enforcement cases per year.

But since 2001, the agency has averaged 19 cases that affect coastal wetlands per year. Coastal wetlands violations may be down on average since 2009 because of agency efforts to better educate the public or possibly because of an increase in civil penalties, spokeswoman Christy Simmons said in the email.

Derb Carter, a long-time attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center in Chapel Hill, said he thinks North Carolina regulators have done well at keeping track of coastal wetlands violations, particularly in the face of budget cuts.

But changes in state political leadership through the years have had an impact on how aggressively coastal laws are enforced in North Carolina, he said.

From 2012 to 2016, then-Gov. Pat McCrory’s DEQ adopted a “culture of customer service” and saw the number of environmental citations issued decline dramatically. That held true for the marshland violations, too, with citations declining in each of McCrory’s four years in office. Under current Gov. Roy Cooper, the number of citations has generally risen, albeit sporadically.

Georgia regulators have had their own enforcement challenges — and one change in the law didn’t help, say Peach State environmentalists.

In 2014, the state watered down a requirement that had for years limited development within 25 feet of salt marshes.

“It was a very political issue,’’ said Sapp, the former EPA lawyer. “You could definitely say there were some influential people on the coast that were trying to ensure there was no buffer.’’

Fortunately, Sapp said, other people got upset about the rule change, causing such an uproar that the state later reimposed the 25-foot buffer rule around salt marshes.

In South Carolina, the Legislature in 2015 issued a “statute of limitations’’ on enforcement of some of the state’s coastal development laws.

The new law said DHEC must levy charges for “minor” violations within three years. The measure easily passed, sailing through the House and Senate.

State Sen. Greg Hembree, a Republican from North Myrtle Beach who supported the legislation, was the lead sponsor on the Senate bill. Former Rep. Greg Duckworth, also a North Myrtle Beach Republican, was the lead sponsor on a virtually identical version of the bill while he served at the time in the House, legislative records show.

Hembree did not respond to requests for comment. Duckworth said he didn’t remember much about the legislation, but several lobbyists brought to his attention what they said was a need for the bill.

Some of the concerns came from property owners in the Cherry Grove section of North Myrtle Beach, said lobbyist Wayne Beam, a former top coastal regulator who once lived in the city.

Cherry Grove, just a few miles south of the North Carolina border, has a long history of disputes over development between property owners and coastal regulators.

Beam, who formerly ran DHEC’s coastal division, said the 2015 law provides a “reasonable statute of limitations’’ for minor violations in salt marshes.

“I don’t think it affected any marsh grass; it was for these little old docks, primarily what it was for,’’ he said.

Von Kolnitz, who runs DHEC’s coastal division in Charleston, said she was not aware that the change in law had hampered enforcement efforts.