Daniella Zalcman's project, "Signs of Your Identity," explores the legacy of Canada's Indian Residential Schools, which began operation in the late 1800s. Attendance at the schools was mandatory, and agents would regularly visit reserves to take children as young as two or three from their communities. Many of them wouldn't see their families again for the next decade. These students were punished for speaking their native languages or observing indigenous traditions. In interviews with the people she met, Zalcman heard stories of routine sexual and physical assault.

The last school closed in 1996. The Canadian government made its first formal apology in 2008. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission that concluded in 2015 officially labeled the system cultural genocide.

Janet cried through most of our interview. Not sobs but silent, steady tears as she talked about her experiences as a child at Marieval Indian Residential School in the 1950s. She told me how she was repeatedly molested by a priest, how she only got to see her parents for two months a year, how, to this day, she hates autumn because it reminds her of having to go back.

"I didn't know who I was," she told me. "I was ashamed to be native, and I was ashamed to be brown, so [after residential school] I ran to the darkest part of the city, where I thought I belonged. We all just want to belong."

Halfway through our conversation, I saw a box of tissues on a side table and handed her one, desperate to offer some kind of comfort. We talked for an hour, I photographed her, we hugged, and she left.

A few minutes later, Deb popped her head through the doorframe. I was sitting in an upstairs room of All Nations Hope, a nonprofit that serves HIV-positive indigenous people in Regina, Saskatchewan. Deb is a staff member there. For me, she's also something of a cultural translator. She immediately noticed the crumpled up tissue on the coffee table and shot me a disapproving look.

"Did you give that to Janet?"

I admitted that I had. Deb is one of my favorite people in the world, but I'm also a little scared of her.

"Never offer a survivor a tissue when they're crying. If they need one, they can reach for it. When you give someone a tissue, you're telling them that their tears need to stop. But tears are good, they're part of healing. Don't interfere with that."

She picked up the tissue gingerly and headed back to her office. In a cabinet, she keeps a brown paper bag, where she collects tissues that people have used to wipe away tears during a smudging ritual she leads every morning. Every so often, she burns them.

I sat there, waiting for my next interview, half embarrassed, half grateful. This is by far the most difficult story I've ever worked on, and Deb is a regular reminder that as much as I think I've done to try to understand and engage sensitively with the First Nations culture, there's a lot I still don't know.

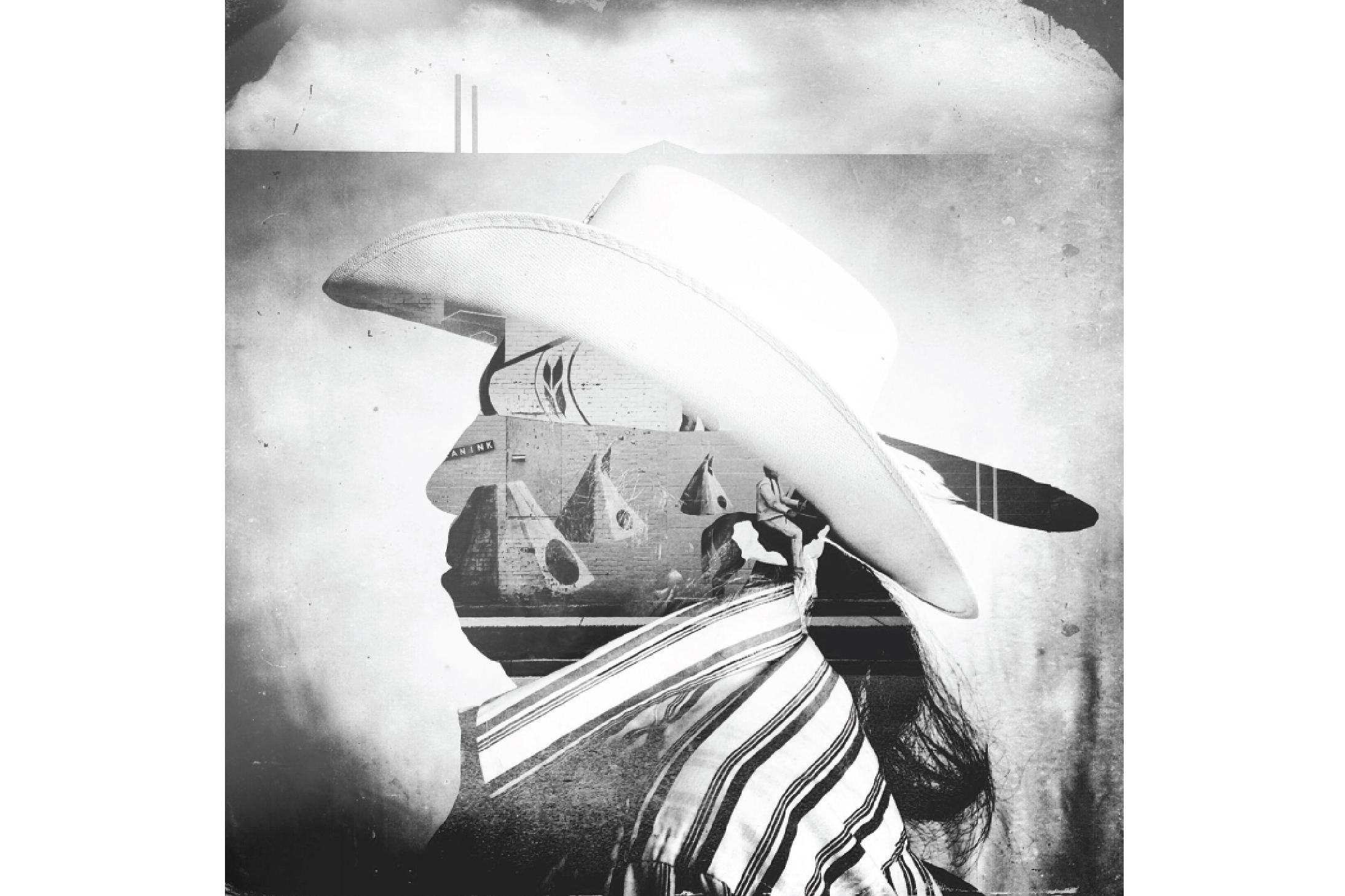

How do you photograph the past? How do you show what remains in the wake of so much trauma and abuse? Every one of the 45 residential school survivors I interviewed had at some point struggled with PTSD, depression, and addiction—but that's not what I wanted to show.

These portraits are my attempt to get to the root of historical trauma. Each of these double exposures layers a former residential school student with something related to his or her experience: the sites where schools once stood, the cemeteries where over 6,000 indigenous children are buried, the documents that enforced strategic assimilation. While alternative processes like composite photography haven't traditionally been considered a part of the documentary arsenal, I believe this is the most effective way to tell these stories. These images are no less truthful than the individual frames that go into them; they speak to the echoes of trauma even as the healing process begins.