Full transcript below:

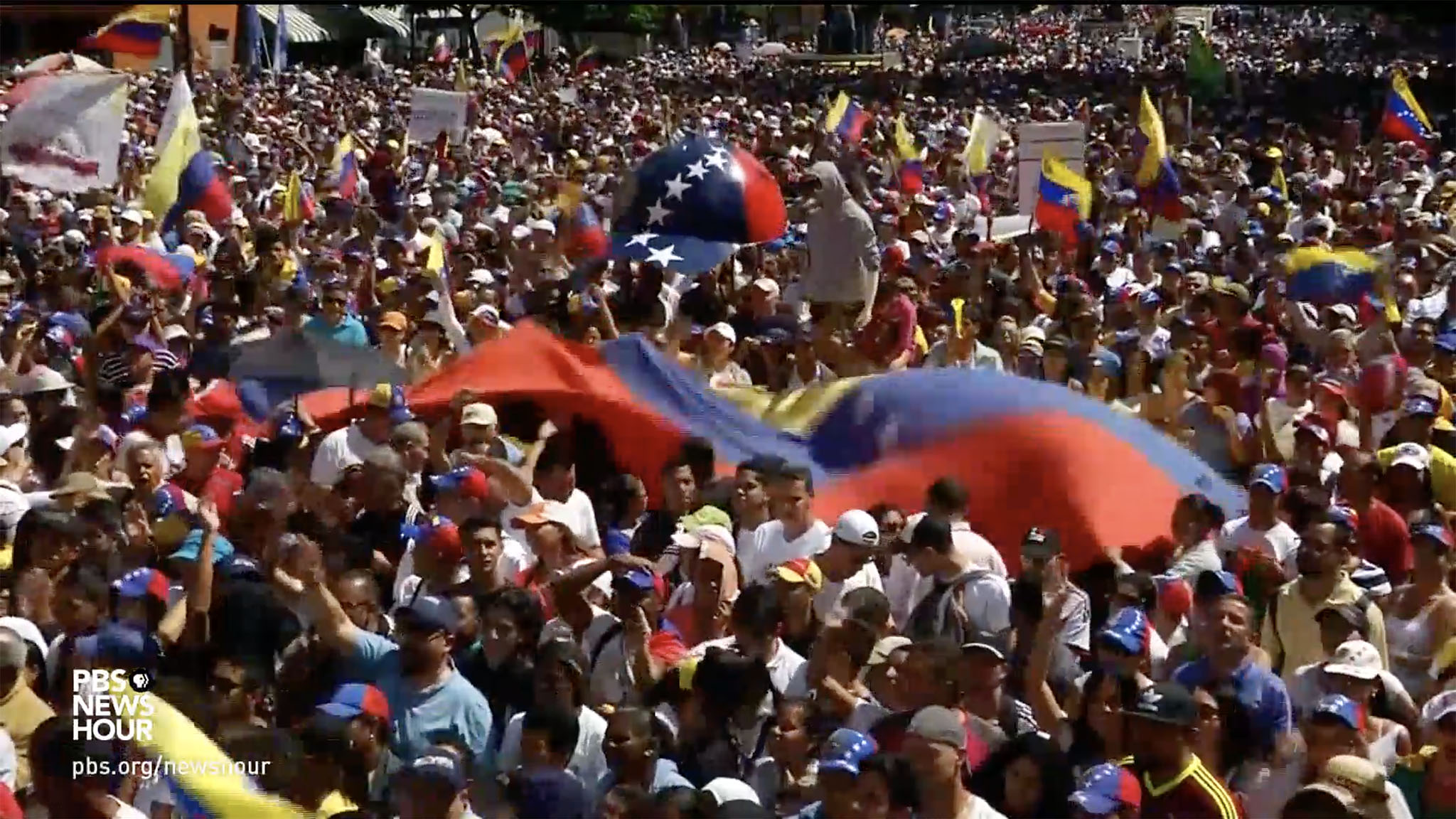

Judy Woodruff: Tens of thousands took to the streets of Venezuela today demanding that aid be allowed to flow into the country, as the political and humanitarian crisis there deepens by the day.

With the support of the Pulitzer Center, special correspondent Nadja Drost and videographer Bruno Federico report from the capital, Caracas.

Nadja Drost: For years now, Venezuelans have hit the streets calling for President Nicolas Maduro to go. This morning, thousands gathered with a relatively new name on their mind, Juan Guaido.

This principal avenue is ground zero of a country on a knife's edge. Now the possibility of someone other than Maduro leading this country has led these throngs of people to heed the call of self-appointed interim President Juan Guaido to demonstrate. Their goal? To apply pressure on the military to defy Maduro's orders and allow humanitarian aid into the country.

Milagro de Soto: I want Maduro to leave and for Guaido to enter. Everyone wants Guaido. Why? Because everyone wants a change.

Nadja Drost: Venezuelans keep adapting their lives to a crisis that only worsens. The line to get on a bus grows longer every day. The number of working buses has plummeted. There's no money to import the parts to keep them running.

Hyperinflation reaching one million percent last year has made food and basic goods completely unaffordable for the average Venezuelan. A hamburger at a food stand costs just over the monthly minimum wage. Most affected by the high food prices are the poor, who have also been the base of support for the late former leader Hugo Chavez, and his successor, Maduro.

But in the traditionally pro-government hillside barrio of La Vega, the graffiti, "Fuera Maduro," "Out With Maduro," signals the shift. At this community kitchen, mothers take turns cooking for the neighborhood's children, using food donated by a member of the opposition.

Residents here aren't used to charity from an opposition with a reputation historically for having little interest in the poor, but Judith Arcia says they're happy to receive the food. The mothers feed 110 children every weekday.

Judith Arcia: There are children who come from school, and this is their first meal of the day, and sometimes it's their last.

Nadja Drost: Another mother, Laura Mendoza, gives kids iron supplements.

Mendoza lives up the street, where she manages her own family's kitchen, cooking with an electric pot in the same room where she shares a bed with her husband and two children. Her husband works at a gas station earning minimum wage, 18,000 bolivares a month, or around $6. Is it enough to get by?

Laura Mendoza: Not at all, because, today, two pounds of rice cost 3,500 bolivares. So do two pounds of flour. The same for pasta. Butter, it's 5,000.

Nadja Drost: Her biggest stress is her children.

Laura Mendoza: At least my children. I don't want to cry. There's times when my kids go to bed without eating.

Nadja Drost: Nothing is worse for a mother.

Laura Mendoza: Terrible, because my kids are hyperactive. But when they are hungry, and I see them lying down, they have no energy, all this because prices go up, and you can't buy.

Nadja Drost: Venezuela's humanitarian crisis has long been denied by Maduro. He rejects offers of international aid as a conspiracy to destabilize the government.

The opposition has decided to take it upon themselves to bring humanitarian aid into the country. Tons of aid donated by the U.S. government sit in the Colombian city of Cucuta on the border with Venezuela. But Juan Guaido and the opposition don't control the borders, and are appealing to the military to disobey Maduro's order and allow the aid in.

But if aid doesn't get across the border, and the high expectations of needy Venezuelans aren't met, opposition member of the National Assembly Stalin Gonzalez says responsibility for blocking the aid lies with those in power and the armed forces.

Stalin Gonzalez: The people will cross the border to look for it. And if they do let it in, people should be able to get it through networks of volunteers who are mobilizing to distribute it.

Nadja Drost: If aid manages to cross into Venezuela, it's expected to help only 5,000 families in a country of 30 million, and likely won't reach people like Laura Mendoza in Caracas.

In the meantime, she has to go out to gather water. Her neighborhood hasn't received water in 10 months.

Laura Mendoza: I take the bottles and carry them in my knapsack, so I can fill them with water.

Nadja Drost: But, today, one neighbor who has water finds her tap dry, another problem Mendoza blames on Maduro. She used to consider herself a government loyalist, but now feels deceived.

Laura Mendoza: They would send me to marches to sign papers. Wherever I was needed, I would go, with the idea that I would receive a house, because look at the situation I live in with my kids. But I never got the house.

Nadja Drost: Tired of waiting for solutions, Mendoza says a change in government is long overdue.

But she was surprised when Juan Guaido suddenly declared himself president. The opposition says last year's election that returned Maduro to power was a fraud. And though they have laid out a path to officially taking power, it remains unclear how they will convince Maduro to cede it.

Stalin Gonzalez: We have got a plan, which is to stop Maduro's usurpation of power, to create a transitional government, and hold free elections. This situation will become unblocked when Maduro understands that democracy requires the possibility of regime change.

Donald Trump: We stand with the Venezuelan people in their noble quest for freedom. And we condemn the brutality of the Maduro regime, whose socialist policies have turned that nation from being the wealthiest in South America into a state of abject poverty and despair.

Nadja Drost: The United States, along with 60 countries, have chosen to recognize Guaido as Venezuela's interim president. They all say it is time for Maduro to go.

With needs and desperation at a high, many Venezuelans are willing to put their support behind Guaido, or perhaps anyone who isn't Maduro. For Mendoza, this is her first time participating in an opposition march.

Laura Mendoza: Enough of Maduro doing what he wants with us. I'm here because I want a new president. I'm ready to vote for whomever to take over who isn't Maduro, for real. The beautiful revolution is over.

Nadja Drost: Mendoza says she feels like Venezuela is on the cusp of a new moment, but first the question is if this current limbo can be overcome — Judy.

Judy Woodruff: And so, Nadja, we know that, for a long time, there have been uprisings in Venezuela that made people think it was going to topple the Maduro government.

And, for years, people have thought that, you know, this crisis was going to get worse before it got better. Does now feel like truly a different moment?

Nadja Drost: You know, Judy, it does feel like a different moment, although I hesitate to say that, because I feel that way every time—every time I come to Venezuela.

It is constantly remarkable how much Venezuelans can survive the crisis and keep on sustaining in what is a really impossible situation. But a lot of Venezuelans feel that now there is a lot of international attention on Venezuela, far more so than before, and that this government's days are numbered.

Judy Woodruff: So, Nadja, we know that the issue of getting humanitarian aid into the country is right now being hotly debated. How do you see that being played out?

Nadja Drost: Well, it's interesting, Judy, because a—the humanitarian aid is normally thought of as being purely humanitarian.

But it has definitely turned into a political issue. The opposition is using the debate over humanitarian aid to basically put Maduro into a corner. He doesn't have any good options. If he allows the opposition to bring aid into the country, he's basically ceding control over territory. That doesn't look good for him.

If he accepts the aid, he's acknowledging that there is a humanitarian crisis in the country, which is something that he has consistently denied. I think that now the question is, how much infrastructure and ability does the opposition have to actually receive the aid and distribute it throughout the country?

There are criticisms that the opposition is raising expectations of a lot of needy Venezuelans about this humanitarian aid, and that they don't, in fact, have infrastructure or capacity to distribute it if they receive it.

And I think that, if they find that they are in a position to distribute aid, and don't do it well, they will lose a lot of credibility.

Judy Woodruff: Nadja Drost, reporting for us from Caracas, thank you, Nadja.

Nadja Drost: Thank you.