The Government of South Sudan is encouraging many new investments in hope that the foreign companies will produce food and ease the country’s food scarcity crisis.

This would be done through the 2014 Drought and Flood Vision Comprehensive Agriculture Master Plan, which envisions commercial production of food through local and foreign investors, said Dr. Loro George Leju Lugor, the Director General of Agriculture Production and Extension Services.

Over 7.1 million people—more than half the population of South Sudan—are at risk of starvation, due to an economic crisis caused by the civil war as well as drought in recent years.

According to the Norwegian People’s Aid-South Sudan, until the 2016 war, foreign investors including ones from the United States, United Kingdom, and some Arab countries owned about 10 percent of the country’s land for extracting resources, oil mining, and agricultural production.

But in 2016, when conflict spiked in South Sudan, many foreign large-scale agricultural companies left the country. Today, most of these farms are still lying idle.

“As we speak, three quarters of the country is going to be hit by famine because we have less food production. We don’t have farm under irrigation now, no, no commercial farm but we used to have them before the 2016 war,” Leju said.

However, the government has now put in place strategies to engage new commercial investors in large scale-food production to meet the high food deficit, Leju said.

This will include more research-based farming to ensure quality food production, he said.

“We have so far divided the country into six ecological zones to ensure food security. We have the Nile corridor, Eastern and Western flat places, Hills and Mountains, Semi-Arid areas and agro-ecological zones,” he said.

Leju says the government will also gazette land into agricultural lands and grazing lands for cattle, as well as national reserve forests throughout South Sudan.

The ministry is also currently rehabilitating the stalled farming machines, some of which were expensive, he said.

He says the fact that land belongs to the people provides opportunities for individuals, families and communities to become easy targets of land frauds in the country.

As far as the government’s plan to “massively invest in food production through investors,” “how they acquire land is not our business because there are people responsible for land matters,” Leju said.

South Sudan, the world’s youngest nation, has been grabbing international news headlines, not for any good reasons but for odd ones including civil wars, tribal conflicts, and land grabs.

Many tribal conflicts stem from fights over the ever-shrinking land and water resources in a less than a decade-old country.

In a place with high poverty levels, massive grabbing of communal land has left herders with little grazing land and affected their traditional water points. Not spared the pain of the wanton land grab are local communities whose major source of water is the mighty River Nile.

Continuing massive deforestation to pave way for commercial investors has also taken a toll on the River Nile banks due to the use of the river’s waters for irrigation.

The scramble for land along River Nile by foreign investors has seen swaths and stretches of hectares of fertile communal lands being allocated without the due involvement of local communities.

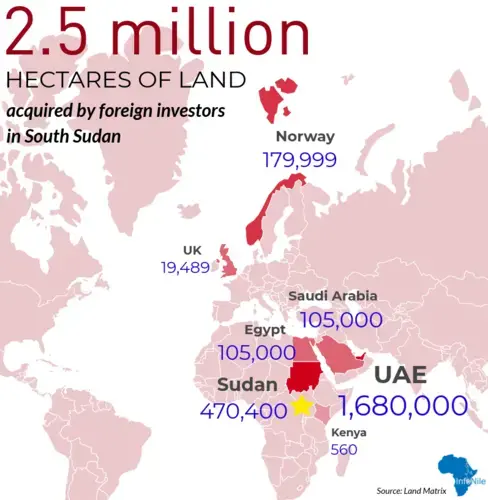

The Land Matrix database, which compiles data on land grabs from governments, companies, NGOs, the media and citizen contributions, has tracked about 2.5 million hectares of land grabbed in South Sudan since 2006. Land grabbing is the acquisition of land without regard for the interests of existing land rights holders.

Most of this land was allocated to 11 transnational deals, with companies from the UAE, Sudan, Norway, UK, Saudi Arabia and Egypt acquiring vast swaths of land for food crops, timber production, carbon sequestration, and tourism.

The land acquisitions were largely in the greater Equatoria region and some parts of Bah erGhazel region. Massive land grabs in these regions were focused on resource extraction, oil mining and agricultural production, RT News reported.

In 2008, the UAE’s Al Ain National Wildlife Company gained a 30-year concession of about 1.7 million hectares to build safari camps and themed wildlife parks within most of Boma National Park, which hosts one of the world’s largest grasslands animal migrations.

In 2009, the Egyptian company Qalaa Holdings acquired 105,000 of prime Nile-irrigated farmland to plant crops for export to Egypt, part of the arid country’s strategy to lessen its dependence on Egypt’s Nile-irrigated fertile valley to grow all of its food.

In 2007, the Green Resources company of Norway acquired about 180,000 hectares in Central Equatoria state to plant teak forests for carbon sequestration. Under the international REDD scheme to mitigate climate change, carbon-emitting companies can buy carbon credits from tree planting companies to offset their emissions.

But such monoculture plantations have long been documented to have a range of negative effects on ecosystems and local communities. A report from the California-based Oakland Institute revealed that in Uganda, Green Resources had evicted local communities, restricted their access to water and grazing lands, and used chemicals that destroy traditional ecosystems.

In other land deals, in 2010, Prince Bandar bin Sultan Al Saud, formerly King Abdullah’s Special Envoy and Director General of the Saudi Intelligence Agency, gained about 100,000 hectares in Gwit, Unity State for agriculture. Now, his land lays dormant.

Nile Lands Parcelled Out

Driving on the nearly 10-kilometre stretch of land on Gumbo to Rajaf Road, about 10 kilometres south of Juba city, it was clear that many parcels of land along the Nile River have been dished out to foreign corporations.

Some sites had erected major signposts with words such as “property of” and “not for sale” to indicate their private ownership. Other demarcated parcels with concrete walls, yet there was no evidence of farming within the plots.

Some sign posts were written in Chinese language, a clear tale of how attractive the River Nile’s lands have been to investors far and wide. One side at a vegetable farm and construction business read, “Sheng DA, Chinese Street No 9, Gumbo, Rajaf Payam”.

In the compound were Chinese nationals, men and women, along with some huge black and healthy dogs. They did not speak English and only engaged their farmhands in gestures. They had huge farming machineries, including stalled earthmovers, ploughing and harvesting tractors: remnants from the 2016 war.

Today, the machines only engage in small-scale vegetable farming and making construction blocks.

Several similar parcels were lined up in sequence, all stretching into River Nile banks.

In the neighbourhood, some compounds were heavily guarded by armed security personnel. Containers of 20 feet and 40 feet in size were mounted on each other: storage facilities owned by container freights firms.

48-year-old Paulina Wani, a Bari by tribe, decried land grabbing in her ancestral land.

The mother of seven said the stretch of land between Gumbo and Rajaf belonged to the Bari community, but individuals have been pushing them out since conflict in the 1980s.

“During the 1983 Anyanya 1 warfare, some people came here to claim were hosting rebels here, so they literally ran over this village. Some of us were displaced by raging perennial floods up the river,” Paulina recalled.

It was at this time that some brokers started targeting their fertile land along River Nile.

She said nowadays, some politicians and land brokers have signed deals with multinational companies to lease fertile communal land for agriculture.

“Can you believe they have grabbed even the small highlands in the river? Those small 10 by 10 feet patches you see there have their owners,” Paulina said as she pointed at the tiny and rocky islands.

Pauline, who said her grandfather owned swaths of land, said today she has been left only with a very small portion of land to host her family and do some small-scale farming.

Some investors who produce soft drinks and go downs for hire have literally encroached into the River Nile banks, erecting concrete walls that stretch into the water itself.

In some case, investors including those in the hotel industry have demarcated their own beaches to tap into the highly lucrative hotel business in Juba, the capital city of South Sudan.

Pushed by the unending land pressures, the River Nile has been forced to redefine its course.

The Nile River’s rugged banks are evidence that it is struggling to breathe and enjoy its once good health.

Lack of Clear Land Laws

Much of the struggle over land arises from a lack of clear land laws and processes after South Sudan gained independence from northern Sudan in 2011, according to Moses Maal, the Acting Director General at South Sudan’s Ministry of Lands.

In many land deals, local governments failed to protect the rights of those originally occupying the land because such people do not have legal land tenure that is recognized by the state government.

“According to the pre-independence Constitution of South Sudan, land belongs to the people – the communities. They use the allotments to enter into deals,” Maal said.

After independence, South Sudanese land policies were taken back to Parliament for review, and no formal new law has yet been passed, Maal said. Currently, the country relies on the pre-independence 2009 Land Act while each state has its own land policies, laws and regulations.

Three groups generally own land in South Sudan: ethnic communities, state and local government, and private leaseholders.

Community land ownership is dominant, which allows communities to use land under customary laws. Government-owned land mostly falls under national parks, game reserves, and forests.

Although private land ownership or private land leaseholders are predominantly found in urban areas, recent foreign investors such as Israeli-owned Green Horizon are mainly interested in acquiring land in rural areas. Such land tends to be leased by communities and government institutions.

Investors take advantage of the lack of proper land laws to enter into deals with unsuspecting individuals and communities, Maal said.

Land Policy in South Sudan Can Help Reduce Land Grabbing and Conflict https://t.co/sI3a38u7C7 pic.twitter.com/LabRcLEyKR

— PaanLuel Wël (@PaanLuelWel2011) January 11, 2017

The South Sudan Land Alliance Secretary General Wodcan Saviour Lazarus said the issue of land is very emotive in South Sudan, especially after the 2013 and 2016 conflicts that saw many civilians flee their ancestral lands for refuge in settlements.

Many lawyers fear to take up land-related cases and face threats because land dispute cases often involve “very powerful individuals” in society, he said.

The 2009 Land Act faces challenges in implementation because of poor human resource and financial muscles to implement the laws, he said.

Several bodies tasked with implementing the Land Act include Payam Land Council, the County Land Authority, State Land Commission and the National Land Commission. However, in some states, Payam Land Council – county land authorities – are non-existent, and where they exist they’re ineffective, Wodcan said.

“South Sudan had only 10 states until the 2016 crisis that saw the birth of 32 new states. This brought further confusion because the units do not have both human and financial muscles to execute their mandates. The confusion has seen some states including traditional courts apply their own traditional laws,” Wodcan said.

The 2009 Land Act allows companies to lease land for a maximum of 99 years. However, the Investment Promotion Act, also passed in 2009, permits only 30 to 60-year lease periods.

To avoid further disputes, the ministry is currently formulating a new Country Land Act, Maal said.

But this process has been long-ongoing: Documents intended to craft the country’s land policy were first presented in 2014 by the chairperson of the South Sudan Land Commission, Robert Lado, at a Council of Ministers meeting chaired by former Vice-President Riek Machar.

“The policy adopted a number of guiding principles, which included security of land rights, equitable access to land and provision of security and diversity in tenure types. The policy divided land into three categories: public, private and community-owned lands,” Maal said.

Maal said the national government should be responsible for public land and the procedure for any investor to acquire land should include identification of the land and informing the state before entering into an agreement with concerned authorities.

“At the moment, these investors you see around are exploiting local people because they refer to the agreements signed before we even had land laws in place,” he said.

William Ebere Amosa, a land expert at the National Land Ministry, said that the new policy recognises the importance of individuals acquiring land and providing them with tenure security, which he said is essential to economic development in the country.

For five years, the Land Policy document has lain in the assembly awaiting parliament’s approval.

However, Musembe Glamourson, a programme officer with South Sudan Land Alliance, said most people do not know that the policy bill exists and so there is need for proper advocacy and awareness creation once it is passed and adopted.

The bill is currently in its third reading and could be passed into law this year, Glamourson said.

In 2013, South Sudan’s cabinet adopted a different long-awaited policy that sought to address some issues pertaining to land acquisition and management in the country.

The new policy was aimed at addressing post-war conflict over land rights, informal settlements in cities and towns, and conflicts over access to land with pasture and water.

Land grabbing and disagreements over boundaries between counties and payams (districts) are also intended to be addressed by this policy.

Community Backlash Leads to Deal Cancellation

Despite the unclear laws, there are some cases of local communities successfully fighting land grabs in the country.

One of the largest and most controversial land deals, which was eventually cancelled due to community backlash, was signed in 2008 between a Dallas, Texas-based firm, Nile Trading and Development, and Mukaya Payam Cooperative.

This $25,000 agreement leased 600,000 hectares of land in central South Sudan to the American company for 49 years, giving the company full and sweeping rights to use the land including for oil exploration, timber, and large scale agriculture.

After a 2008 petition by the Mukaya Payam community alleged that the company did not seek community consultation and more than 600 households would have been displaced by the project, the South Sudanese President, H.E Salva Kiir, cancelled the deal.

30-year-old Jemma Kiden was only 20 years old when the Mukaya Payam lease was signed in her village. She recalled vividly how her grandfather joined hands with other community elders to speak out against the land grab.

“All we saw were big vehicles with strangers moving around our land. Some were whites while the rest were South Sudanese whom we could not even identify,” Kiden said.

Cancellation of the deal was in the best interest of the community, she said.

“How do you hive off communal land for selfish gains, without any due consideration of the host community’s interests? It pains me to see how greed can be used to displace populations,” Kiden said.

Charles Wani is a local farmer in Lanya, several kilometres west of Juba City. He says he relocated to Lanya sub-county after part of his land was allocated to the Mukaya Payam land deal.

“We were never consulted. Nobody even bothered to explain to us what was going on. All we heard was that our ancestral land had been given out, and more painful is that it was given out to a foreign investor at a throwaway price,” Wani said.

“You know very well that land is a very emotive issue in South Sudan. It was good the President intervened; this dispute could have snowballed into a serious conflict,” Wani said.

Additional reporting by Annika McGinnis. This story was first published by Juba Monitor.