Sitting on a brown-leather springy couch that makes him look like he is sinking into quicksand, Carlos Román awaits for his blood to be cleansed. He watches the bright red stream go out of his left arm up the flexible plastic tube and into the dialysis machine. His body carries an excess of salt and vitamins, water, urea and creatinine, all compounds that his kidneys can no longer eliminate. The machine does it for him.

At the Riverside Clinic Dialysis Unit, located in the neighborhood of Chacao, in eastern Caracas, the air conditioning has been broken for months, and the tropical heat floating around seems to warm up a smell of detergent and wet cloth.

The first time he set foot in the dialysis unit, back in 2012, Carlos sat on his assigned chair in a corner on the left side of the room, behind the nurses’ desk. He was enrolled in the morning shift: four hours connected to the machine starting at 7 am every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. He listened to the jokes of the nurses and the muffled echoes from the old television at their desk. The little bulb on top of his dialysis machine glowed green under the dim white light. It never changed to red, the alarm sign that calls up nurses’ attention whenever the patient’s blood pressure goes out of normal levels.

Six years later, almost everything remains unchanged. Carlos sits in the same chair and receives dialysis from the very same machine he was first assigned. He is still on the morning shift: the same four hours, three times a week. There is the same old television, the jokes, the green light that hardly ever shines red.

Only one thing has changed. When he got his first dialysis, Carlos had the chance of receiving a kidney from a deceased donor and getting a transplant that would normalize his life. Now, that possibility is gone.

In Venezuela, organ procurement from deceased donors has been suspended since June 2017, when the government-run Venezuelan Foundation for Organ, Tissues and Cell Donations and Transplant (Fundavene), the entity in charge of managing the organ procurement and transplant system, announced it would not keep up retrieving organs, citing deteriorating hospital infrastructure and scarcity of post-transplant medication as the main reasons motivating the decision.

Eighty-five percent of transplant patients report always having difficulties to find their prescribed immunosuppressants, a post-transplant medication they must take for life to prevent their bodies from rejecting the new organ, according to the National Immunosuppressants Survey, a study by the Organizations of Transplants of Venezuela (ONTV) and the Venezuelan Nephrology Society, which collected data about the current situation of transplant patients in the country.

Patients who do not take this medication regularly and as directed often present medical complications and risk losing their transplanted organ. The lack of immunosuppressants is already having dire consequences in Venezuela. By April 2018, the Inmmunosuppressants Survey had registered 47 transplant patients who lost their organ and 54 who went back to dialysis. The other 26 patients died of medical complications caused by not taking their medication.

The lack of immunosuppressants is part of a broader trend of medicine shortages that has affected the country for years now, leaving thousands of Venezuelans without access to medical treatment and building up to what experts, medical associations, and doctors have labeled a complex humanitarian crisis.

On March 18, 2019, Carlos Rotondaro, ex-president of the Venezuelan Institute of Social Security, the government entity that distributes high-cost medication such as chemotherapy, immunossuppressants, and dialysis material among hospitals and pharmacies nation-wide, said that the number of patients in dialysis in Venezuela fell from 14,824 in 2017 to 11,000 by the end of 2018.

According to Rotondaro, over 3,000 patients with kidney disease died during that period, because of the malfunction of dialysis units across the country and the many faults of the public health system.

Medical literature suggests that in any given country, roughly 40 percent of patients in dialysis could be suitable candidates for a kidney transplant. In Venezuela, an average of 1,600 patients were enrolled on the national waiting list for a kidney in the years prior to 2017, when organ procurement stopped.

As of June 2019, the ONTV estimates that over 500 patients who could have gotten a transplant in the two years since the paralization of organ procurement did not have access to this option. At least 10 percent of them are children, who face an increasing risk of dying as their medical conditions keep deteriorating.

The organ procurement system was put in place in 1997, by the National Organization of Transplants of Venezuela (ONTV, by its acronym in Spanish), an NGO tasked with the mission of professionalizing transplant activity in the country and managing the national organ procurement system.

Transplant activity grew steadily in the following years. The organ donation rate increased from 0.7 donors per million inhabitants in 2001, to seven donors per million inhabitants in 2012. Under the ONTV’s management, the organ procurement system hit a record in 2007, with 345 kidney transplants made, an all-time high for transplant activity in Venezuela.

But in 2014, the government created the Venezuelan Foundation for Organ, Tissues and Cell Donations and Transplant (Fundavene) and transferred the management of the organ procurement system to them. Under the new institution, the number of organ transplants decreased dramatically and in 2017 the system stopped working entirely.

In May 2017, Fundavene sent an official communication to all transplant centers in the country, announcing the “temporary suspension of all activities associated with kidneys procurement and transplant from deceased donors at a national level.” The letter also asked doctors and medical professionals to inform patients on the national waiting list for an organ, that the monthly updating of the list would be suspended until further notice.

“The way it worked was that every transplant center with patients enrolled and ready for transplant, sent their list to the procurement system on the first five days of every month,” explains Eddy Hernández, former ONTV Hospital Coordinator for Transplants and a member of the Venezuelan Society of Nephrology, working at the University Hospital of Caracas and the private hospital Clínica La Floresta.

For a patient to be enrolled on the list, he or she had to attend pre-transplant appointments at their transplant center, have a series of up-to-date medical exams, and request to be included in that center’s list. They had to have a sample of their blood serum, a compound resulting from blood coagulation, taken and stored at the Institute of Immunology of the Universidad Central de Venezuela. This compound was used to make cross tests with available organs to determine if the patient was compatible.

After organ procurement from deceased donors was suspended, the whole system that supported the national waiting list collapsed. Transplant centers were instructed by Fundavene to tell patients “not to send their blood serum samples to the Immunology Institute until they are notified.” The institute stopped giving out appointments for patients to get their blood serum samples taken.

“I used to go there every two months for the serum test,” Carlos says, “but nobody has had the test done since July last year. It’s completely paralyzed.”

“If there are no donors, there is no reason to take serum samples,” says Dr. Hernández. “Why take them and store them just to discard them two months later when they expire, if they are not going to be cross-tested with any donors because there is no organ procurement?”

“The truth is there is no waiting list, because you cannot have a fixed waiting list in which patients enroll and stay forever,” said a doctor at a public hospital in Caracas, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of government retaliation. “If the system was reactivated, we would need to start calling patients to see who is still alive. They could have died in dialysis. We don’t know in what condition they are now: Have they had any blood transfusions? A digestive hemorrhage? Pneumonia? Are their exams up-to-date or have they expired? All of that matters. The waiting list is a mobile, not a static concept.”

A struggle for food and medical treatment

Carlos’s only chance to get a kidney is from a deceased donor. His sister has a toddler and is waiting for her second baby. She cannot risk it. His brother has been fearful. “He’s scared of that,” Carlos says. “As I’ve been taught: it has to be their own will. I cannot force anybody.” After learning about the organ procurement suspension, he stopped going to his regular medical checks. “I haven’t been there in a while,” he says. “Since transplants are paralyzed, I just want to try to preserve myself.”

The country’s general situation makes it harder. For patients like Carlos, everything, from following a restricted diet to finding medication, is an odyssey.

Because of his medical condition, Carlos must follow a diet to keep the toxins and liquids in his body to a minimum. No red meat, because it elevates the levels of creatinine. Canned food is forbidden. Too much fish raises the amount of phosphorus, “and then your whole body itches when you get under the sunlight,” Carlos explains. His fruit intake has to be reduced to avoid excessive water in the organism. “I can only eat a piece of mango, or a single peach every two or three days,” he says. As for water, he can only drink two liters every three days: the same amount a healthy person should consume daily.

Carlos should eat turkey breast and low-salt cheese for breakfast. But on a Wednesday in July 2018, right before going into dialysis, he went for a cheaper option: seasoned mortadella with an arepa made of wheat flour. The high prices of food and the fact that he is the sole source of income for his wife and three daughters constantly keep him off his diet. “I should eat lots of chicken. And to be honest, I haven’t eaten any in six months,” Carlos says. “Earning minimum wage like I do, you just can’t have that luxury.”

In the country with the world’s highest inflation, which according to the International Monetary Fund’s latest projections will hit 10 million percent by the end of 2019, prices go up weekly, and the government's efforts to establish price controls for basic products have created scarcity and set the ground for resellers who sell regulated goods at a higher cost.

According to a report published on May 28, 2019, by Venezuela’s Central Bank, inflation in the country was at 130 percent in 2018 and the economy shrank 22.5 percent in the last quarter of the year. It is the first time the bank publishes any economic data since 2015, when the administration of president Nicolás Maduro stopped showing economic indicators following the collapse of oil prices, the country’s main export and source of revenue.

In April 2019, the Venezuelan government increased the minimum wage to 40,000 bolívares a month, which equals $7.68 at the country’s official currency exchange rate. With these wages, many Venezuelans are now living below the poverty line, which includes people making less than $1.9 a day, according to the World Bank. Venezuelans on minimum wage only make 20 cents a day.

Carlos eats what he can afford: lentils, yucca, boiled sardines, because even the cooking oil to fry them is too expensive. In Guarenas, the town where he lives, 25 miles from Caracas, people now buy “picao” rice, the waste of bad and broken grains usually discarded from rice for human consumption. “We used to give that to the dogs,” Carlos remembers, “but with food prices now, what can I tell you?”

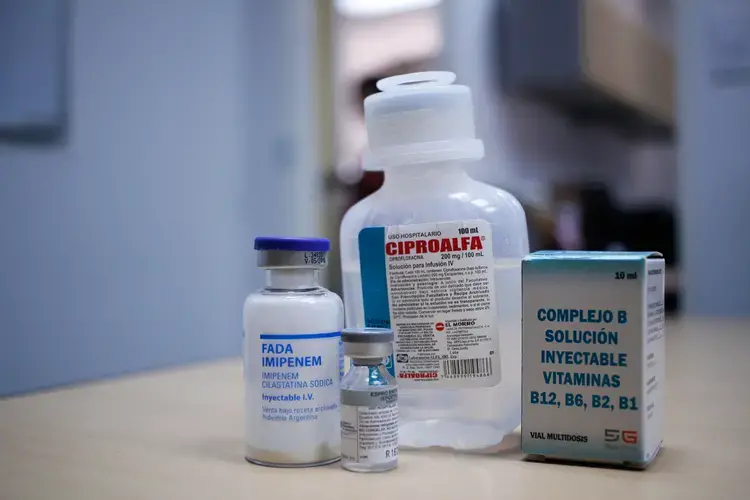

Finding medicine is another of his constant worries. The last time he had a urinary infection, Carlos had to rely on a nurse at a local hospital to find the antibiotics he needed for his treatment. “We became friends and then we traded: I gave her a package of lentils, or black beans, and she helped me with the antibiotic,” he says. “One hand helps the other. But many don’t have that kind of luck.”

Shortages of basic medication and medical supplies have grown in Venezuela in the past couple of years, with doctors and patients often reporting difficulties to find medical treatment, especially for those who suffer from chronic conditions such as diabetes or hypertension. Medicine scarcity is at around 90 percent, according to the Pharmaceutical Federation of Venezuela, which also reports that a total of 400 pharmacies have closed in Venezuela in the past two years, because of the impossibility to maintain their inventory.

The situation has forced many patients to take extreme measures, such as taking less medicine than they were prescribed, consuming expired medication, or even stopping treatment altogether.

For over a year, Carlos has gone through dialysis without Heparin, a solution used to prevent blood coagulation, which could potentially block his vascular access. “They say Heparin ran out in the whole country,” he explains. “Now I get dialysis at my own risk, knowing my blood could coagulate at any moment while I’m connected to the machine.”

Organ transplants: an option for the wealthy

The crisis has also crawled inside public hospitals, where 52 percent of the basic medication required to treat emergencies is not available, according to the National Hospitals Survey, a study published in February 2019 by the NGO Red de Médicos por la Salud, which monitors the state of the healthcare system. The report also found that 1,557 patients died in Venezuela between November 2018 and February 2019, of causes attributable to the lack of medicine and medical supplies.

Transplant centers cannot escape this reality. In the National Immunosuppressants Survey, 72 percent of doctors who specialize in the area of transplants agreed that the lack of medical infrastructure was one of the major reasons why organ procurement stopped. Sixty percent of them also cited problems with supporting services such as x-rays, intensive care and laboratory as another cause.

According to Dr. Carmen Luisa Milanés, a specialist in nephrology who worked as an adviser for the Donation and Transplant Program at the Ministry of the People’s Power for Health until 2014, the country has lost around 80 percent of the specialized human resource in all medical areas related to transplants, including nephrologists, trained nurses and surgeons, many of whom have emigrated looking for more stability and better working conditions “We’re back in 1997 and we have to start over,” she says.

Dr. Milanés explains that the deteriorating conditions of the Venezuelan healthcare system made transplant activity unsustainable. “It is absolutely irresponsible to keep an organ procurement system active when transplant centers cannot operate because there is no induction therapy, or because the patient’s post-transplant treatment is not guaranteed. That is not right. It’s not ethical,” Milanés says.

Organ procurement in Venezuela hit its record 2012, when the system, still under the ONTV’s management, retrieved and transplanted 240 kidneys. In 2016, only two years after Fundavene took over the organ procurement system, the number of kidney transplants made with organs from deceased donors fell to only 25, according to data by the ONTV.

That year, only four of the nine public hospital transplant centers across the country made kidney transplants with organs from deceased donors. All of them combined accounted for only 16 transplants out of the total 25 made that year. The rest were transplants made at private hospitals, where patients have to pay a significant price to access this treatment alternative.

“As of today, transplants in Venezuela are not suspended. What is suspended is the State’s support,” explains Dr. Pedro Rivas, transplant surgeon and director of Fundahígado, the country’s only active liver transplant program. “To have a transplant, you need to have your own financial resources and a living donor. If you don’t, you will not have access.”

Only three private hospitals in Caracas still keep their transplant programs open: Clínica Metropolitana, Clínica Santa Sofía, and Clínica La Floresta. According to Rivas, the cost of a kidney transplant in any of those centers oscillates from $16,000 to $25,000. A liver transplant is more expensive: $60,000 to $80,000. “That can be a person’s life savings,” Rivas says, “the system now is horribly discriminatory. If you don’t have the money, you just don’t have access and you won’t be able to do anything.”

In the first six months of 2017, only nine transplants were made in Venezuela. No official figures related to transplant activity have been published since organ procurement stopped in June 2017.

Fundavene never responded to several requests for an interview.

A day on dialysis

Carlos must be at the dialysis clinic at 7 am. To make it on time he wakes up at 3 am, packs his lunch, and leaves home at 4:30 am, for his 25-mile-journey. The trek is not easy. He must first walk two miles to the bus stop. Once there, he waits patiently in line to hop on an overcrowded bus that goes from Guarenas to the capital city, Caracas. The bus drops him at the eastern edge of the city, where he takes the subway over six stops.

He cannot be late. At 11 am, he must have finished his dialysis. His machine will be used by someone from patients of the afternoon shift and there is no possibility to make up for any missed treatment.

After dialysis, Carlos walks to work, not far from the dialysis clinic. He works as a cashier at a mall’s parking lot from noon to 7 pm. When he gets off work, he has been awake for 16 hours and has around two more to go before arriving home.

On the way back to the town of Guarenas, where he lives, Carlos’s pace is intermittent. After some minutes he feels tired and has to find a ledge to sit or a wall to lean on. Along the final steps, he gives in and calls his daughters. He asks them to come down and meet him at the stop to take his backpack home. Then, the walk back will be a little easier.

“In my current state, I can still do it,” Carlos says. “There are some people that can’t stand for themselves after dialysis.”

The sun is almost at its highest point in the sky, but no light enters into the somber room of the dialysis unit at the Riverside Clinic. Carlos checks the markers on the digital monitor of his dialysis machine. One of them tells him the time he has left: still one hour and 13 minutes to go. Most of his “companions,” as he calls other patients in the unit, are asleep. But Carlos never sleeps. Instead, he looks at them: curled up on the chairs with their mouths open. A sudden noisy beeping breaks the silence. A machine starts glowing red in the corner opposite to Carlos. The nurse on duty walks towards the shrill sound, but before she can reach it, another machine starts beeping. Then another one. And another one.

The nurse stops for a second. She calculates the odds of four machines calling at once. Medical standards indicate there should be one nurse for every four patients in the dialysis unit. But there and then, it is only her. She, alone with the nine patients of the morning shift. Alone with the decision of who to assist first.

It only takes an instant. Then, the machines go quiet again. “Many haven’t made it out of the machine,” Carlos says. “It’s like: I’m sitting here and they are right there and bam! They’re dead. And you’re there, looking right at them. When I first started coming in 2012, we were 25 patients in my shift. Only three are left. Just three from that old guard. The rest are all new people.”