This article was also featured on The Huffington Post.

Rudy Laurent, a 45-year-old resident of Port-au-Prince, says he still thinks about cholera: You never know when it will strike. For many Haitians who live in urban slums around Cité Plus, the neighborhood Rudy calls home, the lack of water infrastructure and sanitation indeed fostered feelings of helplessness in the face of the recent epidemic. Treated water was expensive. Latrines contaminated waterways. To Laurent and his family, cholera seemed to be everywhere.

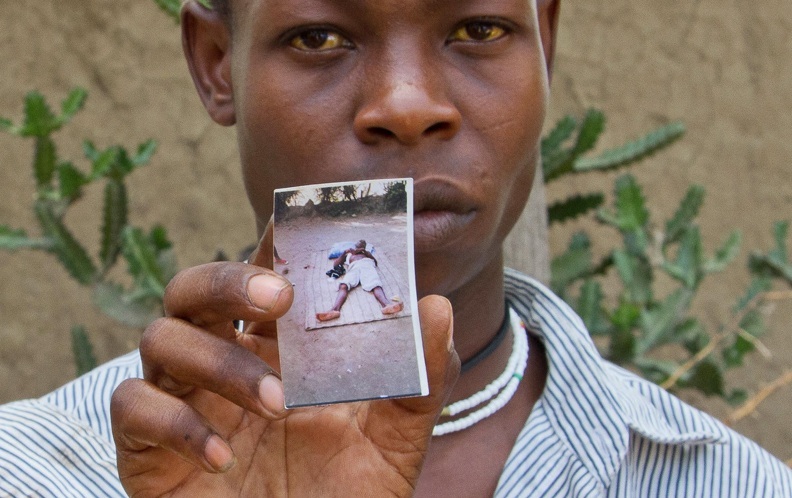

Now, Laurent has a little bit of armor. In his wallet he carries a vaccination card; in his blood he carries two antigens (cell parts that spur the immune system to build antibodies) made in Hyderabad, India – this is the Shanchol cholera vaccine.

Partners in Health (PIH), the Haitian Ministry of Health and Population (MSPP), as well as the nonprofit GHESKIO, recently completed their pilot cholera vaccination campaign. It was no easy road. The vaccination campaign overcame widely publicized political pushback, which resulted in a six-week delay, speculation from the Pan American Health Organization over the timing and prioritization of the campaign, and scheduling conflicts with the national polio vaccine program (the two cannot be administered at the same time to children under age nine).

The vaccine was offered simultaneously in two locations: one by GHESKIO and MSPP around Port-au-Prince, and the other by PIH in communities around St. Marc. New data from the PIH branch, half the total campaign, is positive: Of the nearly 45,000 people that received the first dose of the oral vaccine, 41,193 received the second dose – a 91 percent completion rate. "In terms of GHESKIO's results, they're very similar," said Jonathan Lascher, PIH's Haiti program manager.

Reaching so many people for both doses of the vaccine is very difficult. In the mid-1990s, the United States sometimes attained 87 percent completion rates for the Hepatitis B vaccine among adolescents in urban treatment centers. PIH superseded this number in rural Haiti.

As a result of the delays and setbacks, many were concerned that the cholera campaign missed the early El Niño rainy season – a time when cholera surges. However, in the larger timeline, the campaign may have been luckier than first thought:

"Funding for cholera, and anything health-related, has decreased in the last few months and over the last year," said Cate Oswald, a PIH program coordinator. "Most all of the organizations that you see are stopping their cholera treatment programs." In the long run, the vaccine may have arrived just in time to bridge the gap between Haitians without clean water and the closing of treatment centers.

"It [the vaccine] provides additional protection for people who wouldn't have any," said Lascher. To provide that protection – the two-antigen armor that doctors believe confers immunity in some 70 percent of people that receive the vaccine – necessitates a massive effort. PIH ran community focus groups, talked to community leaders, and blared the message of the vaccine from sound trucks. To spread the word, they even came up with a song.

"We do believe this could be replicated nationwide," said Lascher. The Haitian Ministry of Health is on board as well; in coming years, they will evaluate the potential to include a cholera vaccine in their national vaccine schedule. To further crystallize our knowledge of Shachol's vaccine effectiveness, PIH will soon start a community-based case control study out of the newly vaccinated cohort.

But here's the thing about armor: It is neither communal (Laurent's antigens do not protect others) nor immutable (the protective lifespan of Shanchol stands between two and three years). Armor is a signifier of conflict and constant threat; it is therefore also inherently something that one hopes to someday remove. Right now, there is nothing keeping cholera from arriving in the water of each individual Haitian, so they must continue to carry that armor. In terms of health-related programs, to keep individuals clad in armor mandates that Haiti receive a cholera vaccine every several years.

For no threat of cholera to exist, there must be access to clean water and waste disposal that does not contaminate the aforementioned bacteria-free water. The concept is water and sanitation, a human right, and along with hygiene, the United Nations calls it WASH.

Speaking of cholera as a public health issue, Dr. Jenny Bien-Aime of Doctors Without Borders. said, "In fact, I think WASH is more important than medicine."

In Port-au-Prince, a March 2011 UNICEF survey of 903 temporary latrine systems set up to stymie cholera indicated that there was, on average, one functioning latrine per 148 people, and that 25 percent of the sites experienced open defecation. To put that number in context we can use a pertinent anthropological metric: 150 people is commonly used as a value for Dunbar's number, which is the number of people the human brain can maintain as a close social network. According to the UNICEF survey, the sanitation system in Haiti is such that everyone you know well would use one toilet.

In simpler terms yet, the Pan American Health Organization calls Port-au-Prince "one of the largest cities in the world with no municipal sewage system."

The Haitian Ministry of Water and Sanitation (DINEPA), the group responsible for the municipal sewage system, has its hands full. The fledgling organ of the government was synthesized from component organizations in 2009. Within two years of its inception, it was confronted with the January 2010 earthquake and October 2010 cholera outbreak, a true trial by fire.

However, DINEPA has made strides. Specifically, the ministry collaborated with aid organizations to standardize programs across the country and then opened the first sewage treatment plant in Haiti, followed by the second. Soon, there will be a third.

One of the largest problems facing DINEPA, like most other organizations in Haiti, is money. After the earthquake, DINEPA cited studies that concluded that the country would need $340 million just to provide clean water in Port-au-Prince. Right now, DINEPA has $380 million for water, sanitation, and hygiene in the entire country. Undoubtedly, improvements to sewage and sanitation are less marketable to international donors than vaccines and medical treatment, but they are the only way to keep cholera from ever reaching individual Haitians.

In these two responses to cholera in Haiti, a vaccine and WASH, it is clear that both will save lives. It is necessary to remember, as PIH and most every organization working in Haiti want to stress, that the cholera vaccine is only a part of a larger effort. Although Laurent may now have a little armor, he is still right: As long as he and his family do not have access to clean water and sanitation, he will never know when cholera will strike.

- View this story on Pulitzer Center