GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — After a few weeks of waterboarding the captive in August 2002, the C.I.A. contract psychologists who had developed the interrogation program wanted to stop. The prisoner, a Palestinian known as Abu Zubaydah, was cooperating, and there did not seem to be any point in continuing to torture him.

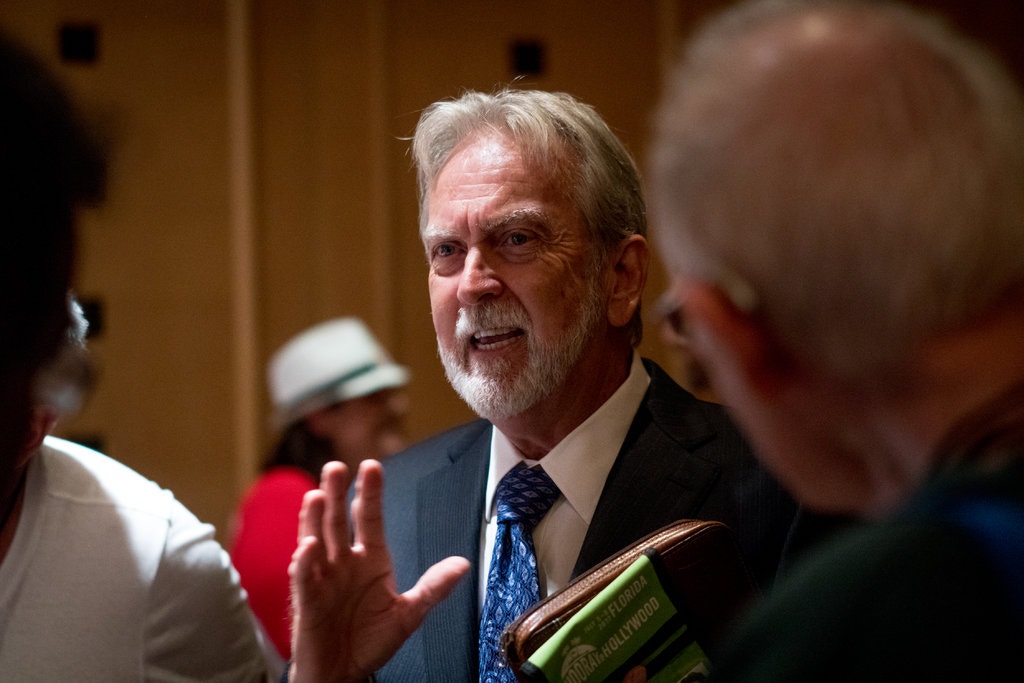

But senior intelligence officials wanted them to press on, one of the psychologists, James E. Mitchell, testified to the military tribunal at Guantánamo on Wednesday.

“Please continue with the aggressive interrogation strategy for the next 2-3 weeks,” their C.I.A. supervisors cabled them, even after the psychologists had sought permission several times to stop using the waterboard and had sent their bosses a disturbingly graphic video montage of what they had been doing.

Dr. Mitchell said those directing the operation derided the psychologists as “pussies” and believed that, contrary to reports from the secret C.I.A. prison in Thailand where they were carrying out the interrogation, Mr. Zubaydah could yield some information about what they feared were looming terrorist attacks. If they would not continue, their supervisors threatened to replace them with someone more aggressive.

So with the support of the C.I.A. station chief, Dr. Mitchell and his partner in developing the program, John Bruce Jessen, summoned a delegation from headquarters to the site to see a real-life version of what had been antiseptically portrayed on television. He quoted himself as saying, “They should bring their rubber boots and come on down.”

The agency dispatched a debriefer from Alec Station, the division that was hunting for Osama bin Laden, and a senior lawyer from the C.I.A.’s Counterterrorism Center.

Dr. Mitchell, describing the incident for the first time in court, said his thinking at the time was: “If you think you want us to waterboard him, then you’re going to witness it. We’re going to do it one more time and then never again.”

In his account in court on Wednesday, he omitted any description of what Mr. Zubaydah was experiencing as guards, the visitors and other black site workers crammed inside his musty, sweaty-smelling cell to watch the waterboarding.

“I don’t want to use the word ‘perfunctory’ about something that horrible,” Dr. Mitchell said, describing how he held a cloth over the Palestinian prisoner’s face as Dr. Jessen did two “20-second pours,” gave the prisoner time to catch his breath, poured water on his face for shorter durations and then concluded with a final, “40-second pour.”

Seven months later, Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Jessen waterboarded Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who allegedly led the Sept. 11, 2001, hijacking plot, 183 times. But Dr. Mitchell, testifying on the second day of two weeks of hearings centered on the C.I.A. torture program, described essentially putting on a show for visiting senior intelligence officials from C.I.A. headquarters to get permission to stop waterboarding Mr. Zubaydah, whom he and his partner waterboarded a total of 63 times.

Defense lawyers in the Sept. 11 death-penalty case called Dr. Mitchell as the first eyewitness of what went on in the C.I.A. interrogation and detention program in the years before Mr. Mohammed and his co-defendants were transferred to Guantánamo in September 2006 for trial.

During his testimony, Dr. Mitchell pantomimed pouring water, as though from a pitcher. Twenty-five feet away, Mr. Mohammed, on trial for his alleged role in planning the Sept. 11 attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people, had headphones on and appeared to be watching a video on a laptop.

“Some of the folks who were watching were tearful,” Dr. Mitchell said in describing the reaction among the visitors who came to see Mr. Zubaydah’s interrogation, including “people who had been there all along who didn’t want to see him waterboarded again. I was tearful. I cry at dog food commercials, and it was particularly hard for me to do.”

“I felt sorry for him,” Dr. Mitchell said of Mr. Zubaydah. “I thought it was unnecessary. He had agreed to work for us,” and aside from the occasional deception, he said, “he held up his end of the bargain.”

In April 2002, as C.I.A. contract psychologists, Drs. Mitchell and Jessen designed a program of violence, sleep deprivation and isolation specifically for use on Mr. Zubaydah. The C.I.A. euphemistically called them “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

Both psychologists were Air Force veterans and drew from experience at the military training program called SERE — for Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape — that subjected United States forces to simulated torture to prepare them for possible capture.

They began waterboarding Mr. Zubaydah in early August. Later that month, Dr. Mitchell testified, they had concluded that they wanted to stop because he was cooperating with his captors and divulging Qaeda secrets.

It was later disclosed that the C.I.A. had mistakenly profiled Mr. Zubaydah as a senior Qaeda official. In fact, he knew some fellow jihadists from Pakistan and Afghanistan and had aspired to set up a rival “terror cell,” Dr. Mitchell testified, but had not yet done so. He has never been charged with a crime and is held at Guantánamo as an indefinite detainee.

Through the day, Dr. Mitchell portrayed himself as a sometime whistle-blower who tried to prevent full-time C.I.A. interrogators from doing gratuitously cruel things in the black sites.

He dispassionately described watching an interrogation of the Saudi man now charged in the U.S.S. Cole bombing case, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, that involved a “stress position”: Guards put a broomstick behind the captive’s knees and bent his torso backward, “pushing his shoulder blades to the floor.”

“He was screaming, and I thought he would dislocate his knees,” said Dr. Mitchell, who said he reported the mistreatment internally. He added that he did not use stress positions in his interrogations because they “don’t lend themselves very well to the kind of classical conditioning I was interested in.”