Uchechukwu Onwa’s welcome party upon his arrival to the United States consisted of a pair of shackles and slightly over two months in a detention center.

Onwa had been working for a nonprofit organization in Nigeria supporting healthcare services and advocacy for LGBTQ+ individuals. He had a visa to attend a conference in the United States and decided that he would seek asylum.

“Back home, I was constantly persecuted because of the work I was doing,” Onwa said. “I was constantly violently and physically beaten up and abused to the point that I was almost killed by [an] angry mob.”

But when he arrived at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport at 5 am on May 13, 2017, he says he was stopped by immigration services and taken to the Atlanta City Detention Center.

“I didn’t even know where we were going to,” Onwa said. “The experience I had there [consists of] things that I really don’t want to think about.”

One in 10 LGBTQ+ adults is an immigrant, and a third of LGBTQ+ immigrants are undocumented, according to Funders for LGBTQ Issues, a network of institutions that provide philanthropic aid to LGBTQ causes and communities. Many LGBTQ+ immigrants seek asylum in the United States due to persecution in their home countries but are met with the harsh conditions in detention centers upon their arrival, advocates say.

“The interesting thing about LGBTQ+ and asylum seekers is that they have really strong claims, meaning that if they have proper representation, they almost always win their asylum cases,” said Kristen Thompson, communications director at Immigration Equality, an organization providing legal aid to LGBTQ+ asylum seekers that has won asylum for over 1,000 LGBTQ+ individuals. “The fact that there are all these barriers to even entering asylum proceedings and getting representation is devastating, given the fact that if they could just get to asylum proceedings and find representation, they could win asylum protections in the U.S.”

There are over 200 immigration detention centers currently in the United States, and 3 million individuals have spent time in a detention center over the past 10 years, according to Funders for LGBTQ Issues. Thompson elaborated on the conditions in detention centers and factors that make it more challenging for LGBTQ+ individuals being detained.

“The Center for American Progress reports that LGBTQ people are 97 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than the general immigration detention population,” Thompson said. “We know that trans women in detention are mistreated in so many ways, from being referred to by their deadname—the name they were assigned at birth—instead of the name that they identify with.”

According to Thompson, trans detainees also are often housed with other members of their sex and not their gender identity, making detention centers dangerous and leaving them vulnerable to harassment. Two trans women seeking asylum died nearly a year apart after having been in ICE custody. In 2018, Roxana Hernandez died approximately one week after she was taken to a hospital in New Mexico with symptoms of pneumonia, dehydration and complications associated with HIV. In 2019, Johana Medina Leon died in a hospital in Texas four days after she was found unconscious in ICE custody.

“In gender-segregated facilities, [trans women] are often housed with the male population,” Thompson said. “If they feel unsafe or face harassment, the only recourse is that ICE puts them in administrative segregation, meaning solitary confinement. The UN has said that solitary confinement is a form of torture, so they are harassed and face violence, or they are tortured.”

Today, Onwa is one of the directors of the Queer Detainee Empowerment Project, a New York-based organization that works to create a community of support for LGBTQ+ and HIV+ immigrants. He was released from detention on parole with support from LGBTQ+ organizations in the United States, as well as friends that he reached out to while detained. Once established in New York, he said he decided to continue dedicating his life to advocacy and helping other LGBTQ+ immigrants.

“I did advocacy work back home, so I thought about continuing that field,” Onwa said. “This affected me, it impacted me, and I want to do something to change the system.”

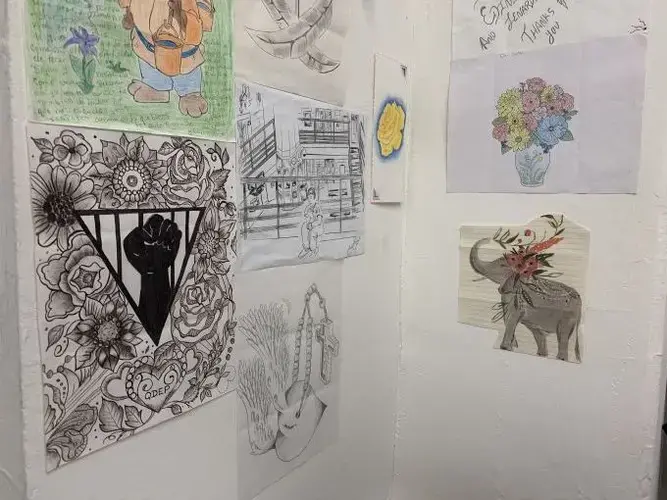

The Queer Detainee Empowerment Project has two main wings of service: its direct services program and its community organizing program. The direct services program targets LGBTQ+ individuals in immigration detention centers and coordinates visits to the centers to break the barrier of isolation and offer emotional support. It also involves a pen pal program during which organization members write letters to those in detention.

QDEP also connects detainees to other LGBTQ+ organizations in order to help move along their cases for asylum and connects clients with housing upon their release. As of early January 2020, the organization had hundreds of volunteers and was working with around 200 clients who were then in detention centers. At the same time, its hotline ran Monday to Friday from 11 am to 5 pm.

Aside from its direct support to LGBTQ+ detainees, QDEP holds weekly community meetings for its members, some of whom were previously held in detention facilities. Attendance at these meetings ranges between 25 and 35 individuals. The community meetings are an opportunity for QDEP’s members to find a sense of community through shared experience. Due to COVID-19, these meetings are currently canceled until further notice, but the organization’s hotline is still open during business hours.

“A big challenge for people, especially LGBTQ+ people most of all, is going through the experience in detention and being released—they don’t know anybody [and have] no family, not friends,” Onwa said. “[The community meetings] form a common network with other people, and make new friends, and share different issues that affect them.”

QDEP member and community meeting attendee Aneiry Lopez came to her first QDEP meeting in hopes that being with other members of the LGBTQ+ community would help her mental health at a critical moment.

“I came here because I was in a depression because I was starting my transition as transgender and I didn’t have any friends at that time,” Lopez said. “When I found out about this organization, I came here, and I started talking and meeting people in the community. That helped me a lot.”

Lopez moved to America from Honduras four years ago. She was initially a teacher in Honduras, but was fired when the school discovered she was gay.

“The school was saying the kids were going to copy my mannerisms,” Lopez said. “I had a big problem trying to get another job. That’s why I decided to migrate: in Honduras, being LGBTQ is not a crime, but you also have lots of problems for being yourself.”

Shane Towler is a QDEP member who attends community meetings. He moved to the United States in April 2018 from Guyana. In Guyana, Towler experienced severe homophobia that made it challenging for him to come to terms with and embrace his identity.

“I was in the police force, so being gay was not accepted,” Towler said. “I had to be this down low, in the closet type of person. The reason why I decided to come to America was because here I can be myself, and I don’t have to be afraid to love a guy, or [a member of] my same sex.”

Towler’s mother passed away when he was young, but even from a young age, Towler feels she knew that he was gay.

“Before my mom died, she told my grandmother, she told everyone, that I was special,” Towler said. “They always say that a mother knows their child, so I guess when my mom was saying that I was special, she was saying that I was different.”

After spending several years in the United States, Towler feels that he is still going through the process of accepting himself—not because he doesn’t know that he is gay, but because of the conditioning he experienced from growing up in a homophobic country.

“Most Caribbean countries like Jamaica, Guyana, and these places, you cannot accept yourself as being gay because these countries are colonial countries that carry lots against gay people,” Towler said. “Because you cannot be your true self back home, it’s hard for you to accept that you are a gay person unless you come out of that traumatic country and be in a country where you are free.”

Lopez feels that her time with QDEP significantly improved her mental health. She recalls an affirming experience from her first time attending a meeting with the organization that made her feel at home.

“The day I came, they asked me for my preferred name and my preferred gender pronouns,” Lopez said. “That was the first time that somebody asked me for it, and they’ve been so respectful of it. I felt like, okay, that’s my house.”

LGBTQ+ immigrants faced barriers to safe immigration and settlement in the United States prior to the Trump administration, but recent legislation has made it more challenging for asylum seekers to find refuge in America. In particular, the administration has changed its stance on affirmative immigration cases: cases in which individuals enter the country on a student or work visa and apply for asylum once they have arrived.

“It’s always urgent, but it’s particularly dangerous for our clients right now and it just continues to get worse,” Thompson said. “The administration put a freeze on processing [affirmative] asylum applications, and so now there are over 900,000 people waiting in this backlog.”

QDEP’s community organizing program, the second leg of its services, centers on empowering its members to become leaders and take initiative when it comes to dismantling systems of oppression and advocating for immigration reform.

“We believe that folks that are affected by an issue are in a better position to make a change for that issue,” Onwa said. “We want our members to be able to advocate for themselves and to be leaders within their community.”

Due to COVID-19, the program is currently holding fundraising efforts to provide materials including antibacterial soap and food to its members in and out of detention centers and communicating information to its members regarding the virus.

Two other barriers to immigration erected by the Trump administration include a quota at ports of entry—meaning that only a certain number of asylum seekers are let in at the border per day—and the requirement that asylum seekers wait in their home countries while their cases are processed.

The administration is also trying to work with Central American countries to make it more challenging for Central American immigrants to successfully seek asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border. Since 90 percent of LGBTQ+ refugees and asylum seekers reported experiencing sexual and gender-based violence in their Central American home countries, according to a 2016 UNHCR study, these regulations impact LGBTQ immigrants’ search for a safe life.

“The administration is working with countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to try to establish them as ‘safe countries,’ so they can say: before you apply, if you have passed through a safe country, you have to apply to and be rejected for asylum in that country before you can apply at the U.S.-Mexico border,” Thompson said. “That’s incredibly problematic because those countries aren’t at all safe for LGBTQ people. In fact, they rank among the highest rates of trans deaths and homicides in the entire world; it’s preposterous to deport people to countries where they are unsafe.”

Onwa wants to give QDEP’s members the skills and resources to take action within their communities to amplify the conversation about LGBTQ+ immigrants’ rights.

“We are working towards giving our members the tools to be able to lead campaigns and launch their own campaigns,” Onwa said.

Towler helps make placards, finalize attendance, and coordinate transportation for QDEP protests and demonstrations. Towler is passionate about using his position in QDEP to represent the needs of LGBTQ immigrants.

“I need to speak out more because I like to do public speaking,” Towler said. “I like to talk a lot, but because of fear, I haven’t been speaking that much.”

Adama Kanazoe, another QDEP member, sought asylum in the United States from Burkina Faso in 2014. He attends QDEP’s weekly meetings and has also been the organization’s chef for the past six months.

“They’re helping people [here], and for me, it’s like a training for how I can help people too,” Kanazoe said. “We are so different but at the same time, we share the same thing, and we love each other like we are from the same mother.”

Kanazoe has been cooking for almost 20 years. He opened his own catering business, Oze Cuisine, in May 2019 and cooks dinner for QDEP’s weekly community meetings. He tries to make foods from different cultures in order to capture the diversity of the immigrant community at the meetings. So far, he has made foods from African, Mexican-American, Italian, and French cuisines.

“For me, it’s a challenge; any dish I make I’m always scared, are people going to like it?” Kanazoe said. “I want my people always to be happy. Cooking, for me, is fun, and it’s a power of connection, because around food, a lot of things can happen.”

Onwa still faces trauma from his experiences in detention but is passionate about advocating for other individuals in similar situations and creating a community for change through QDEP.

“It hasn’t been easy, but at least I’m out, I’m here now,” Onwa said. “I’m with other people that are like me, and I can live my life.”

For Towler, and many others, simply finding an LGBTQ+ friendly family in a new place has provided a sense of comfort.

“It’s meant a lot to know that you are not alone, that there’s other people there with you,” Towler said. “You feel that you are not alone in suffering, you are not alone carrying that burden or that pain. There are other people with you [who] also have that pain and that burden, and they are willing to share it.”