One day in April 2000, Zheng Guangda, a retired teacher from a rural Chinese secondary school then living in New York City, received a phone call from Hong Kong. A former student who knew that Zheng wished to establish an American alumni association was promising to donate $40,000 in start-up funds. Zheng was thrilled. But the promise was never fulfilled; the alumna was arrested the next day, extradited back to the United States, and sentenced to 35 years in prison. In 2014, she died, still incarcerated, after succumbing to cancer. Her name was Cheng Chui Ping — or Sister Ping, as she was broadly known — and she was one of the most infamous human smugglers in U.S. history.

Sister Ping's exploits were most famously chronicled in Patrick Radden Keefe's 2009 book, The Snakehead, which depicted her as the mastermind of a human-smuggling ring and the person behind the Golden Venture, a cargo ship carrying 286 undocumented Chinese immigrants that ran aground at Rockaway Beach in Queens in June 1993. Ping was a major reason that thousands of undocumented Chinese ended up in New York, and indeed nationwide; she is also the reason a rural and otherwise unremarkable secondary school in a Chinese county called Ting Jiang now has one of the United States' biggest alumni associations of overseas Chinese, its 15,000 members easily topping those of many prestigious universities located in major Chinese cities.

This article reflects the results of dozens of interviews with Ting Jiang alumni. Collectively, and almost universally, they consider Sister Ping, also known colloquially as Ping, to be someone who changed their lives; even if she was not their snakehead, her thriving practice paved the way for them, and others. But the wave of Ting Jiang alumni into the United States has ebbed in recent years. China is now a far more prosperous place than it once was, 10-year visas for would-be Chinese visitors to the United States make frequent travel far easier, and China has ended the notorious one-child policy that once prompted many of childbearing age to flee. The changing paths of the alumni have become a prime example of the shifting power between the two countries, as well as the ironies of fate.

Thousands of Chinese with degrees from elite institutions like Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Fudan University have come to the United States for higher education and then gone to work as academics or Wall Street bankers. By contrast, most alumni of Ting Jiang's secondary school are in the United States because they were smuggled in from their hometown in a rural area technically within Fuzhou, a large municipality in southern China, during the high tide of human smuggling from China in the 1980s and 1990s.

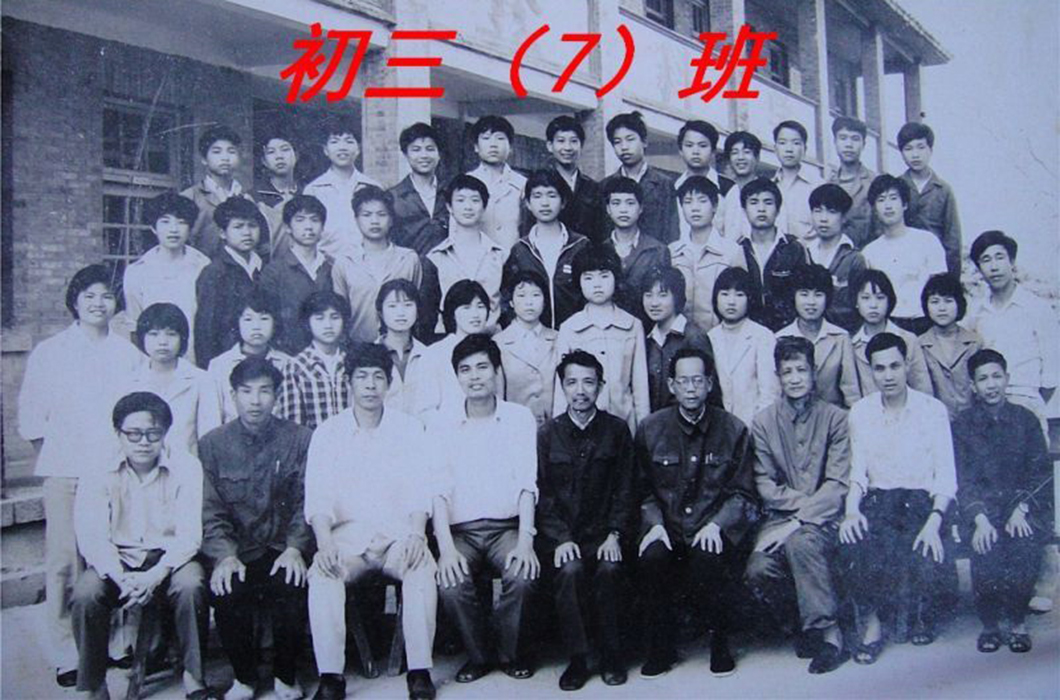

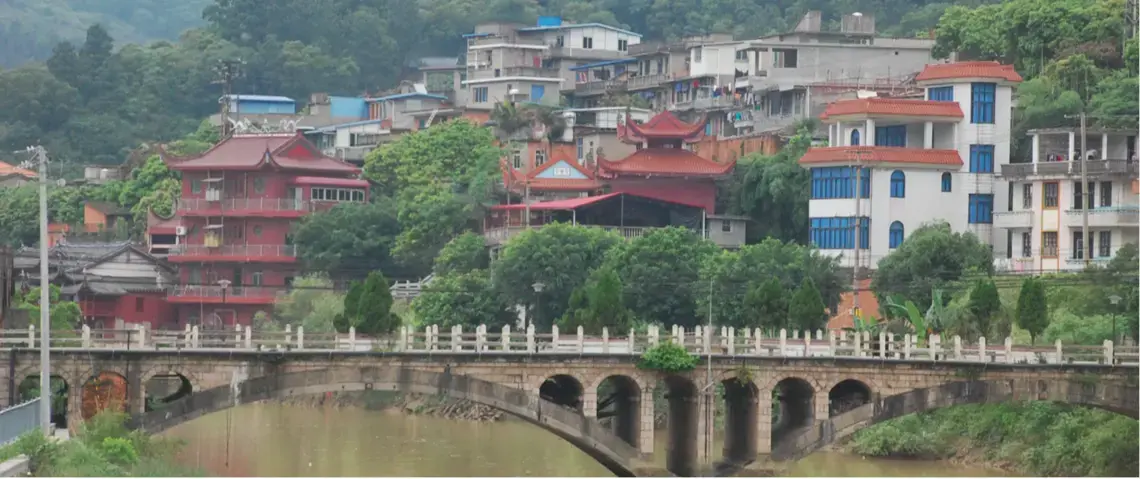

Ting Jiang is a county twice the size of Manhattan, with 17 villages clustered within it. It has always been a tightly knit community, but the connections among villagers are stronger for its major school, founded in 1850. Many Ting Jiang families send all their children there; many have three generations of alumni.

Ting Jiang natives have been going abroad from their mountainous homeland in search of a better life since the late 19th century. At first, its migrants moved to Southeast Asian countries like Singapore and Malaysia in search of more fertile land to farm. An increasingly rich Hong Kong then became an attractive destination in the 1960s.

For a long time, the United States was mostly a destination for Chinese seamen who, upon arriving on U.S. shores to deliver cargo, decided to stay. (Many of those runaway sailors, unable to get legal immigration status in the United States, eventually returned to China.) But in the mid-1980s, new U.S. immigration policies completely changed the picture. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 allowed certain foreign laborers who had worked on U.S. farms to get green cards and also offered amnesty to those who had arrived in earlier years. A 1990 executive order issued by President George H.W. Bush offered legal status to Chinese who had been stateside on or before June 4, 1989, the date of the killing of protesters near Tiananmen Square in Beijing. It also established the one-child policy as valid grounds for political asylum. In 1994, Congress added a section to the Immigration and Nationality Act that offered legal status to undocumented immigrants who could find an employer to sponsor them and pay a fine.

The prospect of gaining legal status greatly accelerated smuggling operations, positioning Ping at the center of Ting Jiang's emigration drive. Ping arrived in the United States in 1981; by 1985, she had become a renowned snakehead in Ting Jiang. Guo Jianbiao, who graduated from Ting Jiang's middle school in 1983, was an early client. After paying Ping $18,000 borrowed from friends and relatives, Guo took a flight to Guatemala on a tourist visa. From there he joined a group for a daylong walk into Mexico. At night, they crossed the U.S. border in a cargo van. The next day, Guo got a plane ticket to Newark, New Jersey, and went straight to a relative's restaurant to work.

"It [was] Sister Ping's business," Guo said. "So the services were quite good. We got plenty of food and water on the way. There were dangerous insects biting us in the jungles while we were walking to Mexico. But I was a country boy, and I was used to this."

The next year, Guo returned to Ting Jiang to visit family with a newly obtained green card he got through amnesty. He was given a hero's welcome; a classmate, Zheng Xiuyu, remembers the brouhaha vividly. "More than two dozen girls stood in a queue in front of his home for him to select a wife. He was only 17," said Zheng. (He is not related to Zheng Guangda, the teacher mentioned earlier.)

Guo's reception contrasted sharply with Zheng's own courtship experience. "When I went to the matchmaker asking to see the photos of the girls in a profile folder, she declined and said those were reserved for people coming back from the United States," Zheng Xiuyu said. "At that moment, I vowed to myself that I had to come to the United States, too." He arrived stateside in 1995 after a zigzagging route through several countries that consumed six months.

By the late 1980s, everyone in Ting Jiang felt the shift. Ou Shuiming, a math teacher at the school, had noticed students disappearing from his class, starting in the mid-1980s. "They didn't tell the teachers they were going abroad. [But] when they stopped coming to school, you knew what happened," said Ou.

The summer after the class of 1990 graduated from the county's middle school, Ou quietly boarded a plane to Thailand. From there, he was told to catch a boat to Malaysia. While onboard, he was given a Japanese passport with his own picture and a plane ticket to Los Angeles. He paid the smugglers $30,000 for the trip.

The journey was smooth until Ou arrived in the United States and was greeted by an immigration officer who spoke Japanese. Ou only knew one word of the language and was quickly exposed. He was arrested, bailed out by a friend the next day, and immediately headed to New York to work in a restaurant run by a distant relative.

By the time Ou arrived in the United States in 1990, about a hundred or so of his own students had already come before him. And the smuggling fee had climbed to $30,000, where it had once been $18,000. But his students kept coming. Eventually about 310 of the 350 members of the middle school class of 1983, Ou's first group of students, had immigrated to the United States.

Ou, who has only recently retired from restaurant work, cannot stop thinking about what would have happened if he had not taken that trip. Had he stayed in China, he could have almost certainly risen to a high place in his beloved field, education. He could have opened his own cram school and possibly made serious money during the economic boom his home country eventually experienced. But Ou could not have possibly foreseen any of this when he left; at that time, his monthly salary was about $32, less than 2 percent of what he made toiling in a U.S. restaurant.

Ou consoles himself knowing that, after coming to the United States, he helped his three other siblings each send a child to the United States. Among them is Zhang Tianxing, a nephew who graduated in 1987 from the same middle school where Ou had taught.

So when Zhang, who came to the United States in 2002, decided to move back to China in 2011, Ou was both baffled and anxious. He knew China's economy was strong; still, hadn't coming to the United States been the dream of everyone in Fujian? Ou couldn't understand why his nephew would give up a green card and a well-paid management job just to return.

For Zhang, however, the decision was clear. Even after landing stateside, Zhang had watched China's economic rise with great interest, investing in the Chinese stock market from abroad and even buying a Fuzhou flat in 2004. "In the United States, I made more money than I could in China," Zhang said. "But the returns of the stock market and real estate market were growing quickly in China." Besides, he added, "In the United States, Fujianese immigrants don't have much of a life. They work hard, and their only entertainment after work is to drink and gamble with family members and friends. I don't want a life like that."

By the time of Zhang's return, going back to China to look for opportunities had become a new trend among émigrés. Almost every class of the alumni association had a few people already heading East, or preparing to do so. The businesses they established in China include hotels, manufacturing and real estate companies, and schools.

One of those enterprising alumni is Ni Zhoumin, a 1985 Ting Jiang middle school graduate. His early story as an immigrant smuggled into the United States traces the arc of the American dream, while his return home says much about the rise of the Chinese dream. Soon after arriving in the United States in 1987, Ni knew he would not be content with mere survival. Within two years, he had saved enough by working 13-hour days at a New Jersey restaurant to partner with a relative and open a takeout restaurant in Atlantic City. By 1991, Ni owned eight restaurants spread across New Jersey, North Carolina, and Virginia. In 1993 — around the time the Golden Venture ran aground, shocking Americans unaware of Ping's massive, ongoing human-smuggling operation — Ni had founded a food distribution company based in North Carolina. The company now boasts 20 distribution centers and serves more than 20,000 Chinese restaurants nationwide.

In 2005, Ni needed to streamline order processing and lower his labor costs, so he set up a call center in Shanghai. Ni hired several Ting Jiang alumni as his company expanded. In 2012, the company opened a branch in Ting Jiang. The person Ni hired to run it is Zhang Tianxing, one of the school's alumni.

Not all returnees have such a happy story. "Other families would be happy to see their loved ones coming back from the United States. But we were deep in sorrow," said Lin Yan, a 50-year-old who runs a boutique shop with his wife in Fuzhou, as he took me to visit his brother, Lin Qiang. Lin Qiang now lives at the Shen Kang Mental Health Institution in the outskirts of Fuzhou. The building is clean and bright, but to see Lin Qiang, we had to pass through two locked fences to get to the visiting area, a reminder that this was not a college dormitory.

Lin Yan and his sister are both alumni of Ting Jiang's middle school. But Lin Qiang, the youngest of the three siblings, dropped out after primary school. In 1992, he became the first in the family to go to the United States with the help of Sister Ping. His first month, he made $900 working at a restaurant that provided room and board. He sent $800 of it home, an amount Lin Yan would have had to work for a year to make in China. In a long-distance phone call after his arrival, Lin Qiang's tone struck his siblings as happy. "He said it was hard work in the restaurant. But he didn't mind because he could make the family live better," recalled Lin Yan.

But the good days didn't last. Four months after the Golden Venture ran aground, Lin Qiang suddenly ceased his regular calls home. The family went into a panic. They asked friends in the United States to look for Lin Qiang, to no effect. They started to fear the worst. "We thought he might have been killed by gangsters," said Lin Yan.

In early 1994, Lin Shan, the sister, paid to have herself smuggled into the United States in order to search for her missing younger brother. Lin Shan worked in Chinese restaurants in New York's Chinatown while on her mission. She posted missing person ads in local newspapers, hired private investigators, and combed through the Fujianese community in the United States. Months turned into years, all clues proving to be dead ends. Finally, a man from Ting Jiang township came to Lin Shan with a promising tip: He had seen her brother in an immigration detention center in Louisiana. Lin Shan jumped into her car and drove 18 hours to the prison where she saw, behind bars, a clearly paranoid Lin Qiang, who couldn't even recognize his sister. "I cried uncontrollably," she said.

Lin Shan later learned that Lin Qiang had been arrested in New York's Chinatown in October 1993, when he was 23 years old, on suspicion of being involved in an assault against an elderly Chinese man. After serving his sentence, Lin Qiang was transferred to an immigration detention facility to await deportation. But because of an incorrect spelling of his name on his immigration jail documentation, the Chinese consulate couldn't confirm his identity. Lin Qiang was left to linger in jail until Lin Shan found him.

Nobody knows exactly what happened to Lin Qiang in detention. But according to Ada Wo, a Chinese-speaking paralegal at Goldberger & Dubin, the law firm that helped get Lin Qiang released from immigration jail in 2009, he was already mentally ill when the law firm took the case in 2005. "He couldn't remember his family members and couldn't tell the authorities how to find them," said Wo.

After Lin Qiang was set free, his sister bought him a plane ticket to China, hoping a hometown and loving parents could alleviate Lin Qiang's diagnosed schizophrenia.

The day I saw him at the mental institution, Lin Qiang told me he was a U.S. citizen, that all the doctors and nurses were undercover agents from the FBI there to persecute him, and that he would return to the United States a month later to marry Hillary Clinton. Our conversation ended abruptly when a nurse announced it was lunchtime. Lin Qiang quickly stood up and scuffled back from the visitor's room to the ward section, which sits behind a locked iron gate.

On the way back from the hospital, my taxi drove past skyscrapers, private cars, well-groomed trees and vegetation, and smartly dressed people. Fuzhou, although considered a second-tier Chinese city, has developed into a modern metropolis. When Lin Qiang left China in 1992, the per capita annual GDP in Fuzhou was about $500 in that year's terms. In 2015, it was reportedly over $10,000. In Mawei district, the area that includes Ting Jiang county, the GDP per capita has reportedly climbed to almost $23,000, quite likely because of all the wealth that émigrés have repatriated over the years. Many people in Ting Jiang now enjoy a comfortable middle-class life. This success casts an ironic shadow on people, like Lin Qiang, who have paid such a high price for their American dreams.

In May, I visited the Ting Jiang school — the source of so many eventual U.S. citizens and the starting point for Sister Ping's now infamous smuggling business. When I asked students about the possibility of going to the United States, few showed interest. "My English is not very good. So I plan to go to college in China," said Duan Wenfeng, a senior in the high school. Tang Yujie, a freshman in the middle school, told me, "My dream is to become a white-collar worker in China. Maybe a CEO."

I brought up the possibility of being smuggled to the United States. But it was clear that the spot that was once ground zero for illegal Chinese immigration into the United States had entered a different era. Several students broke in at the same time: It was too dangerous. It was something "only our parent's generation" would do. One added, "If I want to go to the United States, I can go there [legally] to study."

Huang Qingyu, the school principal, told me that in the five years since he took charge, not one among the 130 teachers had left for the United States. Every year, a few students still departed for the United States before graduation. But they all had parents who'd gotten U.S. citizenship and were legally bringing children over for family reunions. "Nowadays with the internet, young people know more about the United States, more even than us," Huang said. "They all consciously choose their future."

The Ting Jiang school has recently been expanding. Since 2013, the city of Fuzhou, which controls Ting Jiang, has given the school about $16 million in grants. It has a new gym and is in the process of purchasing additional land for a new playground. Huang pointed to a banyan tree, which had stood on the campus since World War II. "I told them no matter how we build or rebuild, that tree has to stay there," Huang said. "So when our overseas alumni come back to revisit, they can find some old memories."

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Rong Xiaoqing

Rong Xiaoqing reported in the U.S. and China on the twists and turns in the lives of a few dozen...