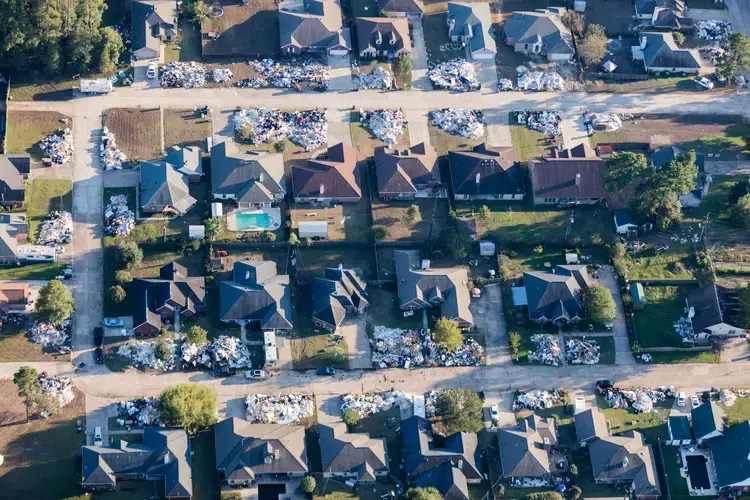

BEVIL OAKS, TEXAS – Alex MacLean – whose aerial images illustrate this story – and I recently cruised toward Bevil Oaks, Texas, on Rt. 105. A few miles out of town, we swerved around a tattered blanket in the road. It had probably flown off one of the procession of dump trucks carting flood-soaked waste from Bevil Oaks buildings to a mountain of debris rising nearby.

We passed a platoon of yard signs advertising mold abatement, drywall removal, and homes for sale.

Flooding wrought by Hurricane Harvey had rampaged through Texas about a month earlier. In just a few days, Harvey had spilled five feet of rain in a record-breaking downpour that scientists see as indicative of more extreme weather events in years ahead.

In Bevil Oaks, about 80 miles northeast of Houston, floodwater had poured into almost every ranch house, saturating and contaminating inside and out, staining and destroying interior walls. Tall stacks of trash now filled front yards.

Most of the houses in Bevil Oaks, about 10 miles northwest of downtown Beaumont, were empty. Residents were still sorting out insurance claims and making plans to rebuild.

Although few there may agree, Bevil Oaks now stands as a harbinger of the extreme weather events scientists see occurring more often as the climate warms.

The post-Harvey experiences of Bevil Oaks provide some insights regarding an obvious question: Why is so little being done across the U.S. to avoid (or even to prepare for) the increasing flooding devastation that global warming will usher in?

We turned onto Oak River Drive. It dead-ends at Pine Island Bayou, the usually-docile stream that had swelled and engulfed the town in late August. In the last block, towering above a patch of spindly oaks, stands a commemoration of the storm: a flood gauge – a tall white ruler bolted to a metal pipe – erected years ago for recording previous inundations. A red arrow labeled “1994” pointed at a tick mark eight feet above the ground. In that year, slow moving remnants of Hurricane Rosa had soaked southeast Texas, breaking local river-flow records and destroying 3,000 homes. A record breaker at that time, it seemed unlikely to soon be exceeded.

In search of a house to ‘flip’ for a ‘tidy profit’

As we parked and gawked at the monument, a man pulled up in a pickup and stuck his head out the window. “Is this a flood zone?” he yelled. I motioned to the gauge and the new tick-mark in turquoise paint that somebody recently had drawn near the top. That mark, at the height of the flood Harvey unleashed, was four feet above the 1994 pointer – twelve feet off the ground.

The man, David Dickens, turned out to be a real estate speculator from Beaumont. He said he’d driven past one of the swamped houses. Its owner had gutted it and put it on the market for $140,000 less than its pre-storm value. At that price, Dickens told us he could now flip it for a tidy profit.

Bevil Oaks is in a “flood zone” in an obvious sense. The town is pretty flat and only a few feet above Pine Island Bayou’s banks. When the stream overflowed in August, it washed through all but four of the city’s 560 homes. Most of them were swamped in five to eight feet of water. The only undamaged houses were four that had been built on stilts.

Dickens was asking about building rules, not about the likelihood that the house he’d seen could soon be inundated again. He wanted to know if, in an official bureaucratic sense, Bevil Oaks is a good place to buy a house, and, if applicable flood rules permit reconstruction, and resale of the house.

He was in luck. Yes. The city had recently relaxed rules meant to encourage housing stock that’s less flood-prone.

Bevil Oaks has regulated home construction for flood safety for decades. Since 2007 it has required, under a rule called Ordinance #207, that the first floor of a home stand at least two feet above FEMA’s “Base Flood Elevation.” BFE is a height that the agency determines water will reach at any given spot in a “one hundred-year flood.” FEMA designates those as ones having a 1 percent chance of occurring in a single year. Bevil Oaks’ Ordinance #207 applied only to new construction and, “major renovations.” Nearly half of Bevil Oaks’ homes had first floors below the two-foot benchmark. They’d been grandfathered in.

After Harvey struck, every flooded home required major renovations. And the Ordinance #207 elevation requirement newly applied to scores of homes that had previously been exempt. Two hundred and thirty-seven flooded homes had been built below the two-foot benchmark. They therefore couldn’t legally be reconstructed unless the concrete slab foundations were raised onto dirt mounds or stilts. That is a construction feat not covered by insurance.

Bevil Oaks officials feared that much of the community would be unable to afford the cost of rebuilding and would abandon the property and town. It might have been “Good bye, no more Bevil Oaks,” says Kimberly Vandver, the city’s Certified Floodplain Manager.

Opening the way for ‘a rebuilding boom of sorts’

On September 28, a month after the flood, the City Council responded. It suspended the two-foot requirement for a year, permitting reconstruction even when a home’s first floor is at the Base Flood Elevation. The rule change did not cover 44 homes with first floors below BFE. They’ll have to be raised or demolished. Still, the change saved the town for now, and set off a rebuilding boom of sorts.

FEMA calculates BFE by extrapolating from past storms. But such actuarial forecasts might no longer be trustworthy for projecting future risk, says Kerry Emanuel, a hurricane expert at MIT. “Because the climate is changing, the past is not necessarily a good guide to the future.”

Imagine loading a pair of dice so they’re more likely to roll ones: The probability of throwing snake eyes would increase. Emanuel says that global warming increases the odds that Texas will experience more of the most powerful category of storms. Not all storm researchers agree. But they do widely accept that warming increases the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere, and therefore adds to the amount of rainfall a storm can carry. For this reason alone, the prospects for more severe flooding are increasing.

From 100-years flood to … every five years?

Emanuel has studied the impact of global warming on Texas hurricanes by computer-simulating thousands of possible past and future storm tracks. In a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences summarizing his results, Emanuel tabulated the chance of a storm soaking Texas with more than two-thirds as much water as Harvey. In the final decades of the 20th century, the chance of such a storm was about one percent. The chance at present is six percent. By the end of the century the risk will triple, to 18 percent. A hurricane carrying that much water would drench part of Texas once every five years.

“Those certainly are alarming numbers,” says John Nielsen-Gammon, a professor of atmospheric science at Texas A&M University. Nielsen-Gammon, who is also the Texas State Climatologist and who occasionally collaborates with Emanuel, says he agrees that global warming is bringing heavier rainfall in Texas and elsewhere. “That’s almost as certain as the rise in temperature,” he says. And yet, he says he is awaiting further research before he’s convinced that the results of Emanuel’s new study of Texas rainfall are robust.

Lisa Roberts invited Alex and me into a snug single-story house on Sweetgum Road in Bevil Oaks, where she’d grown up and lived with her mother until it flooded halfway to the ceiling. She told us that if the City Council hadn’t suspended the two-foot rule, she and her mother would have had to raise the house by four inches. She said they couldn’t have afforded the additional work, which she estimates would have cost her $70,000-$100,000.

With Hurricane Harvey flooding, 'you don't know what you've lost when you've lost everything.'

“This was the master bedroom,” Roberts said, in commencing a post-apocalyptic real estate tour. She stepped through a doorframe (she’d unscrewed every sodden door) into a half-gutted room, furnished with only a floor lamp. Black splotches of mold covered the remains of the walls. In the kitchen, Roberts and her brothers had pulled down the drywall and ripped up the floor, leaving only the custom cabinets that her uncle had built. Roberts said they too would have to go.

Roberts had set aside a few treasures she’d fished from the ruins. Protected from the rain, under the eaves, she’d stashed a vinyl record – encased in a now-waterlogged sleeve – of songs sung by her childhood pastor’s wife, and a baby doll with a cherubic plastic face. Recently, she’d discovered a pair of diamond earrings she’d forgotten about: a present she’d given to her mother. “You don’t know what you’ve lost when you’ve lost everything,” she said.

A climate change influence? Or ‘an act of God’?

Jim Blackburn, an environmental lawyer and professor at Rice University, is a frequent gadfly in Texas flood protection debates. He says it’s understandable that Bevil Oaks leaders would weaken flood protection rules to keep their tiny city alive. But he says the U.S. must wake up to the increased risk of flooding brought by climate change. “We’re looking at unprecedented rainfall,” he says. “This is where the denial of climate change is devastating.”

In the parking lot of the Bevil Oaks First Baptist Church, residents took breaks from shoveling up their possessions and hauling them to the street en route to a local landfill. They chatted softly while picking over pallets of free cleaning supplies and canned food donated by the Red Cross and two religious charities.

Don Smith, the town’s Emergency Management Coordinator, was at the church parking lot, talking to residents and other city officials. I asked him if global warming might make future flooding more likely.

None dare call it climate change

Nope, he said. Harvey “had nothing to do with climate change.” He said that nobody ever mentioned that concept to him. The storm was “an act of God.”

Andrew Dessler, also an atmospheric scientist at Texas A&M University, said in a phone interview that that’s not quite accurate. He said the primary reason Harvey dropped so much rainfall is that it slowed down and “stalled” above Texas. “That was just bad luck.”

But Dessler also said global warming probably did make the storm carry more water. “It’s reasonable, though not certain, that we increased the rainfall by some amount.” His said he estimates that climate change added about 10 percent to Harvey’s downpours.

The morning we visited Bevil Oaks, Judy Donnell, a shuttle bus driver employed by a local hotel, had advised us to avoid talking about climate change. The Beaumont economy runs on oil production, she said. Oil companies built several of the country’s largest refineries in the region. She said that she knows about global warming but doesn’t discuss it much.

“It’s best to keep your opinions to yourself here,” she said. “Nobody wants to talk about it.”

Education Resource

Meet the Journalists: Daniel Grossman and Alex MacLean

After Hurricane Harvey aerial photographer Alex MacLean and journalist Daniel Grossman flew across...