CYNTHIA CARTER YOUNG thought of Leonard Carter as her “big little brother.” He was younger than her, but so protective that he was more like the older sibling. “He always wanted to look out for other people,” she says.

Last spring, she was looking forward to seeing him again. After almost 25 years in prison, Leonard, 60, had been paroled and had only weeks left to go until his release. Then, on April 14th, Cynthia got a dreaded call from a No Caller ID number. “I said ‘Oh, no,’ and picked up.”

Leonard had died from Covid-19. “If he’d lived, he would have had a chance to see his grandchild for the first time,” she says. “What he wanted to do most was hug his grandchild.”

Almost 200,000 people over 55 are in prison in the U.S., according to Bureau of Justice data from 2017. Thanks to tough-on-crime laws like mandatory minimums and stringent parole boards, the number of older incarcerated people jumped 282 percent between 1995 and 2010. Elderly prisoners are arguably the most vulnerable population to the ravages of Covid, yet efforts to release them through compassionate release or home confinement have been halting at best.

“So many of us have lived in fear for our elderly loved ones this year, but it’s so much worse for those with family in prison,” says photographer Natalie Keyssar, who spent six months documenting elderly prisoners and their families in New York state. “They have no way to stay safe while incarcerated.”

Jails and prisons around the country have been at the center of clustered outbreaks, which is not surprising given the conditions. Inmates eat together, drink from the same water fountains, use the same telephones, share toilets. There isn’t adequate space to socially distance, and prisoners often lack proper PPE.

NAWANNA SNIPE TUCKER is not used to hearing fear in her husband’s voice. But when Covid-19 hit the Otisville Correctional Facility, Curtis, 55, told her he was scared. “When the numbers started going up, nobody really knew what it was,” she says. “People were getting terrified.” Prisoners are considered elderly at 55 because they have the health issues and comorbidities of older citizens. Curtis has been incarcerated for more than 30 years for double homicide. Nawanna is helping him navigate a wrongful-conviction claim but struggles to stay hopeful after so many dead ends.

Instead of releasing a sizable number of inmates to home confinement, state officials punted and even allowed the jail population of New York to balloon during the pandemic. Sandhya Kajeepeta, who researches incarceration and health at Columbia University, tells Rolling Stone that the small drop in incarcerated people in New York jails following bail reform was swiftly reversed after fear-mongering about rising crime. “Bail reform was rolled back by the state in July. Almost immediately after, we saw the New York City jail population rise.”

Attempts at reducing incarcerated populations have focused on reforming bail and releasing people from short-term sentences, but when it comes to elderly prisoners, it's parole reform that would have the biggest impact. Many elderly prisoners are still locked up because they are serving lengthy if not life sentences and were convicted of serious crimes, which has made them ineligible for home confinement during Covid.

But the recidivism rate for seniors is extremely low — as little as three percent, per one study — and the cost of caring for them in prison is much higher than the risk that they will be a danger to society. "It serves no purpose other than revenge to keep elder people in prison until near death,” says Jose Saldana, director of the advocacy group Release Aging People from Prison (RAPP), who himself served a 38-year prison sentence and was released in 2018 at the age of 66.

“I think that the fundamental premise of mass incarceration is permanent punishment or near-permanent punishment,” Saldana says. “So when you sentence people to harsh sentences and then you provide little opportunity for release, this is going to create a crisis.” Especially in a system that disproportionately incarcerates black and brown people. “If a white kid were hurled into prison to serve 75 years to life, at the rate that black and brown kids are being sentenced today, there would be a public uproar,” says Saldana. “It's just throwing our kids into prison like they never existed.”

Critics say that inmates get too few chances at parole, in a process that often lacks transparency and doesn't take into account how people have changed while incarcerated. Two bills introduced in the New York state legislature hope to address that — one would instate a “presumptive parole” approach, which would prioritize whether the person has been rehabilitated, rather than the seriousness of the crime they were convicted for, in making parole decisions. The other, an “elder parole” bill, would automatically grant incarcerated people over 55 a chance at parole so long as they've served 15 years of their sentence. Saldana estimates such a bill could help 350 to 400 prisoners in New York right away, and thousands of people in the years ahead.

“I think that you have to give people hope, first of all, and you have to give them the opportunity to return back to their families at an age where they can be productive,” says Saldana. “Not only would they be a responsible member of their family, but they will also be a civic minded citizen returning to their community with the moral obligation of repairing harm that was done.”

Leonard Carter had hoped to mentor former inmates through a nonprofit when he got out, says Cynthia. But he never got the chance. “He was granted parole after serving 25 years,” Cynthia says, “and along came Covid-19.”

This project was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the Magnum Foundation.

DE’ANNA MONTGOMERY

DE’ANNA MONTGOMERY, Nawanna’s adopted daughter, likes to make “dream boards” about her hopes for the future. She wants to be a K-pop star when she grows up, and, more than anything, for Curtis to come home. “He is the only father figure she’s had since she was a week old,” says Nawanna. “She asks me when he’s coming home all the time.” The 10-year-old spoke at a rally commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Attica uprising. “I have told her she has a voice and she can use her voice,” Nawanna says.

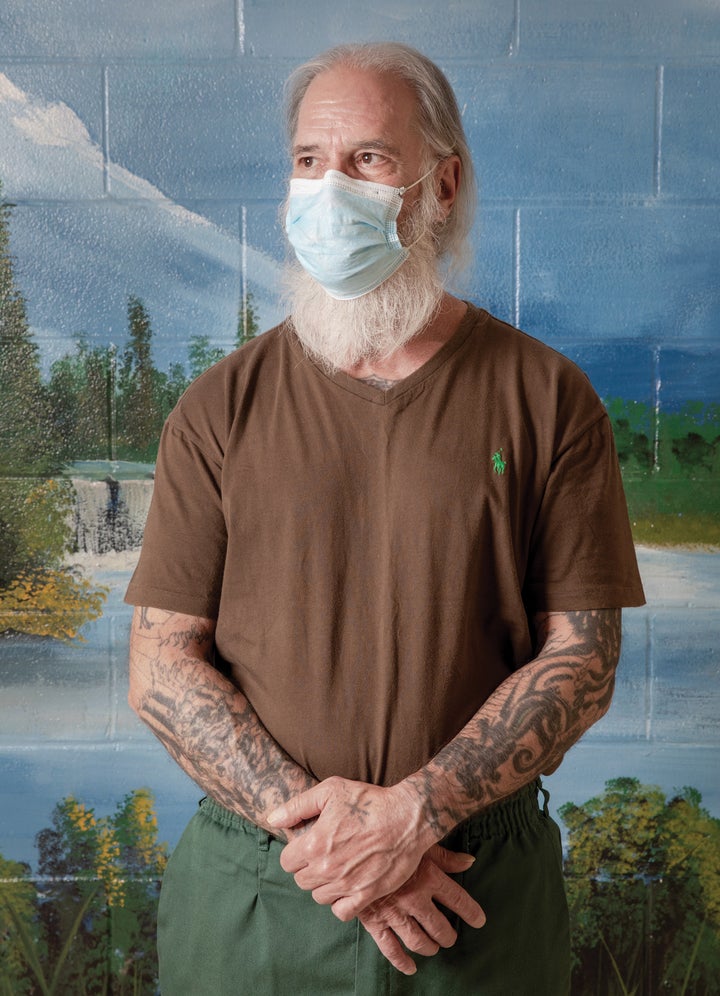

EDWARD MACKENZIE

WHEN EDWARD MACKENZIE went to prison 28 years ago on kidnapping and drug charges, the old-timers advised him to keep up his health in the hope that he’d be free one day. At 65, he now suffers from high blood pressure and shoulder and back injuries. “I’m getting old and falling apart,” he says. He was moved to the Adirondack Correctional Facility last year, which the state is using as a prison for elderly inmates during the pandemic. Critics say the center was underprepared to handle the health needs of elderly people and that it mixed a high-risk population together without testing them for Covid. For Mackenzie, it also meant he was too far away from his sister, Darlene, for her to visit. “I got a granddaughter. She's 28. I been in jail her whole life,” he says. “During this incarceration, I lost my whole family: my mother, my father, two brothers, every aunt and uncle I had. That’s the hardest part, not being there for my family when they needed me.”

The only thing that can change is me. And I changed. So what do you want me to do, die in here?

—EDWARD MACKENZIE

It's devastating to the child [when their mother's in prison]. Their whole life is turned upside down … The child rebels, and you create a prison pipeline with that.

—ROSLYN SMITH

ROSLYN SMITH

THE FIRST TIME Roslyn Smith was confronted with self-checkout at the grocery store, she thought she was going crazy. It made no sense. “I was like, ‘How do you do that?’” Then again, even crossing a street felt foreign following her release from prison, in 2018, after serving 39 years. She was 17 when she went away. She’s now 58.

“I lost so much,” she says. “I lost my uterus. I had a hysterectomy while I was in there. I lost so much. I lost experiences of growing up, of going to a college. Of seeing the world, traveling.”

Smith worries about all the friends she has who are still on the inside. “They didn’t give them hand sanitizer. They didn’t let them social distance. The officers would not wear masks,” she says.

Smith, who got her bachelor’s degree while she was in prison, now works as the program manager for the Beyond Incarceration program at V-Day, an activist collective focused on ending violence against women. She says she tries to stay positive but is angry and sad about how sexism and racism in America combine to take away the freedom — and lives — of women of color.

ATTICA ANNIVERSARY RALLY

ON THE 50th ANNIVERSARY of the Attica prison uprising, activists protested mass incarceration, inhumane treatment of inmates, and the handling of Covid-19. “It opens your eyes to the corruption of the criminal-justice system,” says Emma Graham, whose husband is serving a 25-year sentence. “The men in Attica demanded simple things: toiletries, showers — what [prisoners] are still fighting for. Nothing has changed."

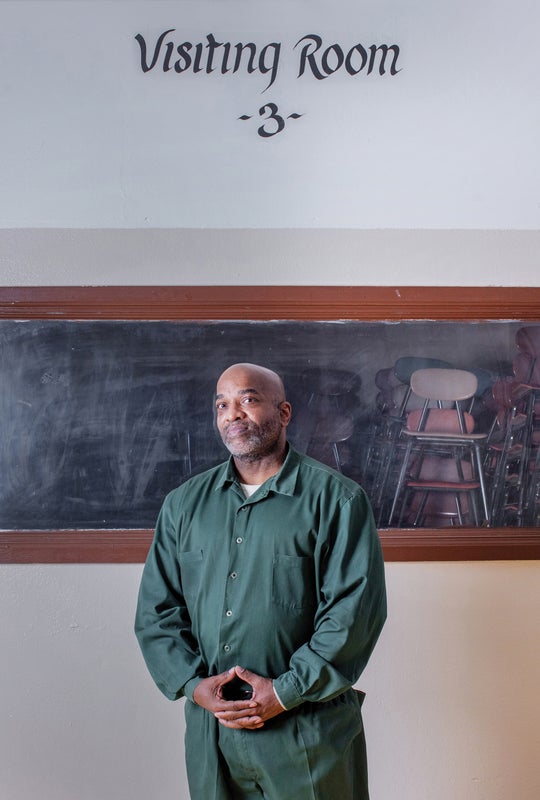

ALMOST 40 YEARS AGO, Robert Lind was involved in a shootout with police. No cops were injured. Nevertheless, he’s not eligible for parole until 2032. His wife, Michelle, has not been able to see him since November because they’re both high-risk. “I’m all he has,” she says. “There’s no one else. No one goes to visit him, or he doesn’t call anybody else, or everyone’s dead.”

Robert is now 74 and was recovering from treatment for prostate cancer last spring when he got Covid. He suffered from symptoms for months after getting out of the hospital: “My left leg was swollen to three times its size. I couldn’t walk in a straight line. A lot of coughing, headache, and chills.”

He teaches an anti-violence course in the prison and says he can’t fathom why the state keeps elderly people like him locked up, especially in a pandemic. “You have to serve a sentence,” he says, “but when you see an individual that walks through a hallway and trembles, or a really sick individual who’s mentally challenged, what is that? Enough is enough.”

Michelle is scared she won’t see Robert alive again if he doesn’t get a compassionate release. “The only way he’ll come home to me is in a body bag,” she says.

ROBERT & MICHELLE LIND

If I could go in and speak to guys in one of these county jails, I would. ‘You gotta change your ways, take it from me, man.’

—ROBERT LIND

SABRINA SCOTT

SABRINA SCOTT HAS KNOWN HER HUSBAND, Todd, since they were kids. She’d had a crush on him, and was shocked, along with the rest of the neighborhood, she says, when he was convicted in connection with the murder of a cop (she maintains he is innocent). “I saw the way he took care of his little siblings,” she says. “I knew what it was like to come from a lot of trauma at home. Todd was a protector and a provider even at 16, 17.” Years later they reconnected, marrying in 2019. In October, he contracted Covid and has struggled with long-term symptoms. “Every time my phone rings, my heart is in my shoe,” says Sabrina. They were holding out hope for parole this year — he’s served more than three decades and has been a model prisoner, living in one of the “honor block” cells. But right before Christmas, he was denied parole again.

CYNTHIA CARTER YOUNG

CYNTHIA REMEMBERS her brother Leonard as a prankster and a sharp dresser who wore alligator shoes and liked to bake cakes for family and friends. She is outraged by his death from Covid in April. He’d paid his debt, had been paroled and deemed no longer a threat to society, but the state would not expedite his release to protect him from Covid-19. They grew up in a large religious family in Brooklyn that felt the whole of his absence for 25 years. “The family goes through the correctional process also,” she says. “The whole family goes to prison.”

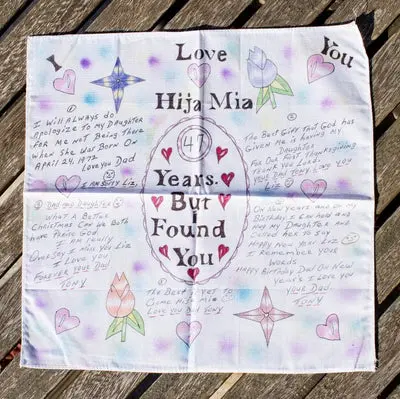

ELIZABETH MEDINA

ELIZABETH MEDINA never knew anything about her father. So when her mother died a decade ago, Medina felt like an orphan. But a year ago, she found a note at her door from lawyers telling her that her father was alive, incarcerated, and trying to reach her. “When the lawyers told me this was real, it wasn’t bull----, I broke down. I was crying,” says Medina, 48. She was a bit shy the first time she met her father, who has been in prison practically her whole life. He did most of the talking. He gave her some of the toys and drawings he’d been making her for years. Fearful of using shared telephones during the pandemic, he emails her every single day. “Obviously, we’re bonded now,” she says.

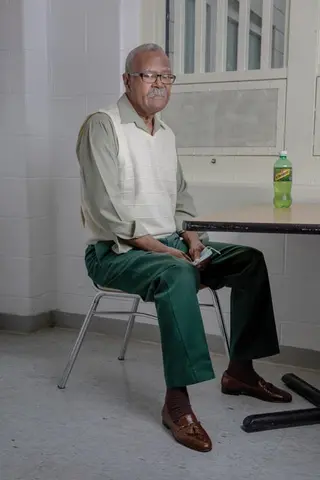

KEVIN HAYES & SUSAN LI

WHEN STAN LI, 67, called his daughter on her 19th birthday, he had to put a sock over the phone protection against Covid-19. “He has a very… he had a very Buddhist outlook on life, take it as it is, so he’d never complain about anything,” says Susan Li. But she knew to be worried when he admitted that he’d lost his sense of taste and smell. “Two weeks after my birthday, he was declared dead,” she says.

Afterward, Susan connected with Kevin Hayes, her father’s 58-year-old cellmate at the Fishkill Correctional Facility. Hayes himself tested positive for Covid after Stan did, but was not symptomatic. He was sent into solitary confinement for 21 days to isolate. In lieu of space to quarantine prisoners, correctional facilities have increasingly relied

on solitary. Jacq Williams, a criminal-justice-reform advocate, says there’s no safe amount of time to keep a person in solitary. “According to the Geneva Conventions, over 15 days constitutes torture,” she says. “The damage has been extreme.” Hayes is serving 25-to-life, but has already done 28. He hopes he’ll live to visit the grave of his son, who died in 2017, and to help out with his grandson. “He’s 14, he’s at the age when things happen,” he says. “He’s a good kid, and it’s not like I’m a stranger to him, but his father is dead and I want to help fill that role.”

“We’re not just statistics,” says Susan. “My father was a lot more than the way he passed away. He was a full human being [who had] a community, a family, people who cared about him.”