This story was originally translated from Spanish. To read the original story in full, visit El País.

A large European logging group has irregularly converted more than a dozen of its logging permits in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) into so-called conservation concessions. After extracting the most valuable tropical timber from 15 of them — covering an area the size of Belgium — the Portuguese-owned Norsudtimber group now plans to invest in projects to sell carbon credits in the former logging areas.

To date, nature conservation concessions in DRC have basically been used to do carbon credit sales projects. The DRC outsources the management of some of its protected areas to NGOs such as WWF, but these are public areas, whereas a concession is a piece of land that the state cedes to a private company or individual for a period of time in order for them to make an economic return.

Since the end of 2020, the DRC has allocated 24 new nature conservation concessions in the second largest rainforest on the planet in a gesture spurred by the interest of investors in carbon markets. That is: individuals and companies, such as airlines, can offset their greenhouse gas emissions by investing in initiatives that absorb that CO₂ elsewhere on the planet. This is done by buying and selling so-called "carbon credits" on international markets. In theory, this allows private initiatives to earn money by protecting forests — such as the Congolese — through a type of carbon project known as REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation).

An investigation by EL PAÍS/Planeta Futuro has obtained unpublished documents showing that, in December 2020, outgoing Environment Minister Claude Nyamugabo signed contracts transferring millions of hectares of concessions from Norsudtimber's logging subsidiaries (Sodefor and Forabola) to Kongo Forest Based Solutions (KFBS). The latter is another subsidiary of the same corporate group created to manage its carbon trading operations.

Whistleblowers and others in possession of sensitive information of public concern can now securely and confidentially share tips, documents, and data with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), its editors, and journalists.

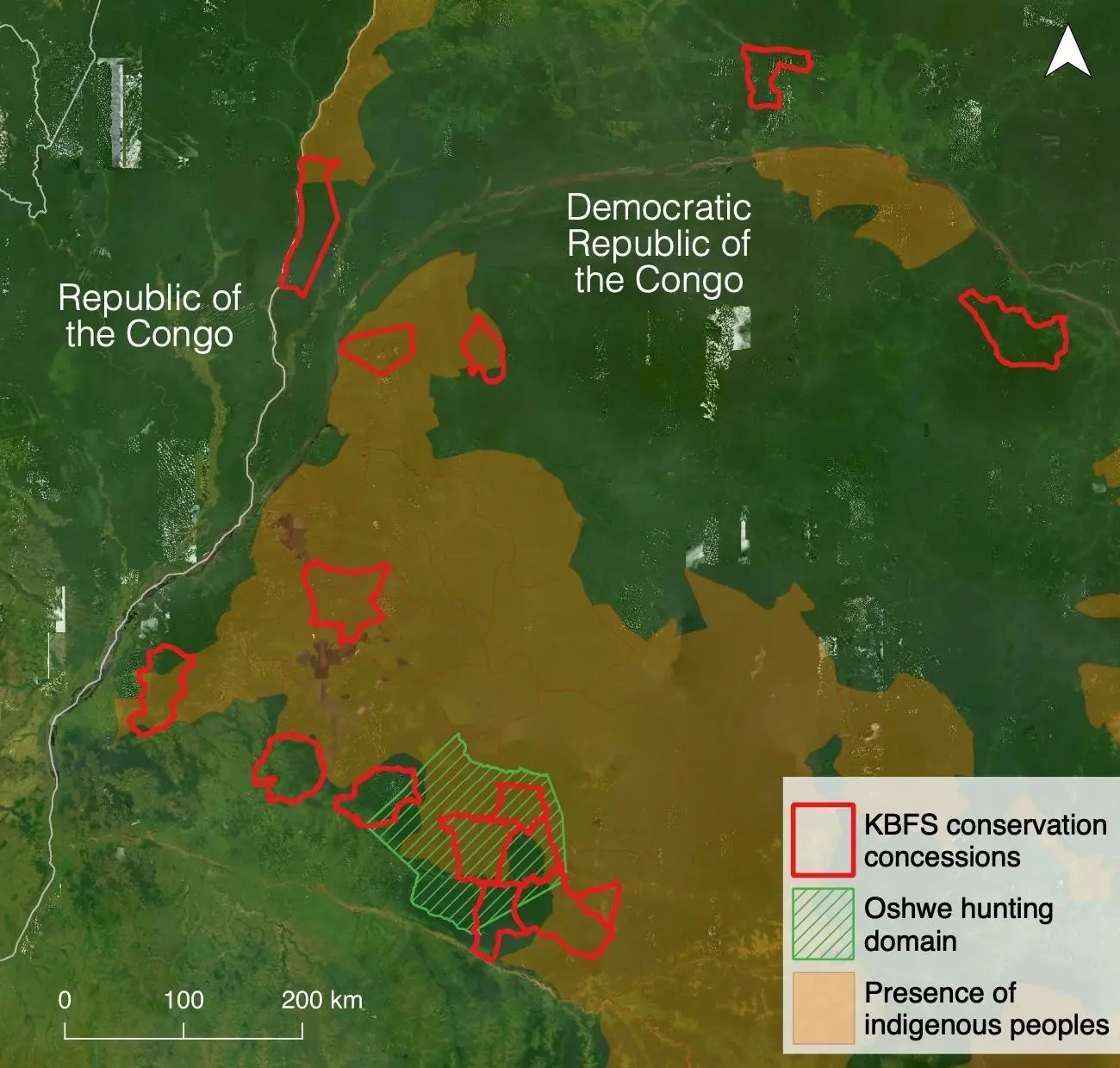

The concessions were reallocated out of the public eye and without involving local populations. Several of them overlap with a protected area and the ancestral lands of the Bambuti, Bacwa and Batwa peoples, and almost a third of the area is peatland, a type of wetland vital for the climate and for the development of the people who live there.

As lessees of conservation concessions, entities such as KFBS must look after valuable ecosystems and protect the well-being of the communities that depend on the forests for their livelihoods. The forests of the DRC are home to endangered species such as pangolins — the world's most trafficked animals — chimpanzees and okapis. They also regulate the temperature and rainfall patterns of the entire region, and their trees store a third more carbon per hectare than the Amazon.

But KFBS's leases, with durations ranging from 30 to 44 years, defy Congolese law, which requires financial and technical plans to be presented at a joint meeting with officials and communities. The aim is for all of them to have the same information and be able to assess whether the project meets the requirements of each party. "The minister brokered the deal," says a senior environment ministry official in Kinshasa, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. "Nyamugabo knew he would lose his post in a cabinet reshuffle, and he wanted to eat as much as possible before losing his chair."

The former minister is accused of allocating an additional 4.4 million hectares in the north and west of the country in 2020 in violation of DRC laws. This includes nine conservation concessions.

- December 16-18, 2020. Minister Claude Nyamugabo awards 15 conservation concessions to KFBS.

- March 27, 2021. Sodefor and KFBS inform Tshopo Province of the new conservation title in the area.

- April 12, 2021. Éve Bazaïba appointed deputy prime minister for the environment.

- May 1, 2021. Sodefor notifies the new concession to the communities in Isangi, Tshopo.

- October 2021. Jurists call for suspension of 22 other titles signed by Nyamugabo, nine of them conservation titles.

- October 31 to November 13, 2021. UN Climate Summit (COP26).

- November 2, 2021. CAFI signs a 10-year agreement with the DRC.

- January 1, 2022. DRC fails to meet the first target of the CAFI agreement.

- Mid-April 2022. Deadline for EU-funded timber title review.

Norsudtimber is controlled by Portuguese brothers Alberto Pedro and José Albano Maia Trindade, who run both its logging and carbon activities. Alberto Pedro represents the industrial logging companies Sodefor and Forabola, while José Albano represents KFBS, which is in charge of new projects for the sale of carbon credits.

Global Witness, which is one of the world's leading environmental research NGOs, alleged in 2018 that the Norsudtimber group violated the DRC Forest Code in 90% of its concessions. Norsudtimber denied any wrongdoing.

Facts and Figures

Congolese law requires entities interested in conservation concessions to formally involve all parties before signing contracts. But in this case, the provincial authorities only received a courtesy letter informing them of the conversion months after it had taken place.

This newspaper obtained one of the letters, received by the Tshopo provincial environmental authorities in April 2021. It was sent on March 27, when Minister Nyamugabo was still in office. "We have the honor to inform you that Sodefor has recently transferred its 59/14 forestry concession […] to KFBS. It is now a conservation concession," the company notes. KFBS then asks for the support of the province so that the project can move forward "in a participatory manner."

The DRC is one of the most opaque countries in the world in terms of financial transparency, and it is easy to take advantage of its regulatory loopholes. The 2011 decree on the attribution of conservation concessions, for example, does not explicitly mention the conversion of existing logging titles.

Few know the nooks and crannies of DRC's green laws better than Augustin Mpoyi, a soft-spoken Congolese who combines his roles as one of the country's leading environmental lawyers and one of its most relentless activists.

As a lawyer, he has worked on landmark laws such as the 2002 Forestry Code and a new land planning policy. As founder of the NGO Codelt, he was the first to bring an environment minister to justice for abuses of power in the DRC, and has called on the government to suspend dozens of concessions that experts say are illegal. The government has already committed to cancel six of them, all conservation concessions.

Conservation concessions are a matter of public interest that requires the free, prior and informed consent of the communities, as well as the participation of the provincial administrations from the very planning stages, clarifies Mpoyi. "Everything must be done with maximum transparency, and not even a minister can circumvent the procedures established by law," he says. "So yes; the creation of those 15 [KFBS] concessions is very, very, very problematic."

Going for the Signatures

Forest-dependent communities are supposed to be at the center of REDD+, a United Nations mechanism that seeks to combat climate change through reducing CO₂ emissions produced by deforestation and forest degradation by offering alternatives to common practices such as slash-and-burn agriculture.

But the inhabitants of Isangi — a lush territory in northern DRC with giant leopards and land pangolins — were informed of everything that was to be undertaken on their land for the first time, five months after the contract was signed.

In December 2021, company representatives delivered slate and roofing materials to the communities as final compensation for the logging activity. The local chiefs then signed a new agreement that the company needs to issue carbon credits. Among those attending the meeting were the territory administrator and the province's environmental coordinator.

In the document, KFBS commits to pay €3,100 per month to each of the communities and 8% of future carbon sales, as well as to keep them informed of fluctuations in the price of carbon credits.

Perez Bolengelaka was at the meeting as a representative of Isangi's civil society. As he explains, KFBS did not discuss financial and technical plans, nor did it explain the project's activities beyond general references to nature conservation. Nor did it describe what options they would offer to people who depend on shifting agriculture and artisanal logging. "To look at all this information properly and hold a proper consultation would have taken days, but the meeting went straight for the signatures," Bolengelaka declares. "It's a shame. A real partnership could have been forged."

A Rainforest at Stake

Congo's rainforest is unlike any other. It is more impenetrable, more pristine and a more potent carbon sink than its counterparts in Southeast Asia and Latin America. Scientists recently confirmed that the Congo Basin has the world's largest tropical peatlands, a type of forested wetland that locks up thousands of tons of carbon in the soil, accumulated over thousands of years as semi-decomposed organic matter.

Nearly one-third of KFBS's concessions are in peatlands, and several of them overlap with a protected area in Oshwe, in Maï-Ndombe province in southwestern DRC.

Two of the titles in Oshwe belonged to KFBS's sister company, Sodefor, until Minister Nyamugabo awarded them to Congolese company Groupe Services as logging concessions in June 2020. In October 2021, Congolese jurists formally requested the Council of Ministers to annul these contracts for violating the moratorium on the allocation of new industrial logging concessions. What they did not know was that Nyamugabo had already reallocated them nine months earlier. They were back in Norsudtimber's hands, now in the form of conservation titles.

One of those jurists is Augustin Mpoyi. Upon hearing about it, he shakes his head in disbelief. "It's not possible… This is a scandal."

Jeff Mapilanga of the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN) says protected areas should not overlap with private concessions, including conservation concessions. "We first heard about these concessions before the UN Climate Summit in Glasgow," he says.

Controversial History

The Norsudtimber deal is the latest in a series of controversial contracts signed by Nyamugabo, a protégé of former DRC President Joseph Kabila. The latter is now facing accusations of having embezzled 123 million euros.

In 2021, Congolese civil society took legal action against the former environment minister, something unprecedented in the country's history. The NGOs, led by Codelt, accused Nyamugabo of illegally allocating an area of forest the size of Denmark. In this context, the government admitted "the illegality of many contracts" at a Council of Ministers meeting just two weeks before the COP26 Climate Summit in October. This included six conservation concessions granted to Tradelink, a company founded by Belgian and Italian investors involved in logging and mining.

At the climate summit, the European Union and the United Kingdom pledged 1.3 billion euros to protect the Congo Basin's forests, while the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI) announced a ten-year agreement, with a contribution of 200 million dollars (about 180 million euros) for the first five years. CAFI is funded by Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, South Korea and the EU.

The CAFI initiative is helping the DRC meet the requirements for lifting the moratorium on new industrial logging concessions. The measure was put in place 20 years ago to prevent the plundering of equatorial forests in the aftermath of the Second Congo War, which officially ended in 2003. More than 40 international environmental NGOs led by Greenpeace and UK Greenforest Foundation argue that the country is not ready to end the ban.

"The truth is that keeping a logging concession under control is easier than controlling a forest that is open to all kinds of informal activities, including unregulated logging by local communities and even organized groups," says François Busson, a natural resource expert with experience at the Central African Forestry Commission. At least, he says, as long as the new concessions are legal.

"It Is Not in the Public Interest"

Planeta Futuro presented the research findings to the concession holders. In an email response, KFBS said, "Your descriptions of the facts, which we did not explicitly comment on, should be understood as irrelevant to us and do not merit a [response] from us."

KFBS argues that the Nyamugabo-led Ministry of Environment had considered the conservation concessions to be the result of a transfer between subsidiaries of the same corporate group, rather than new attributions. He also stresses having followed the authorities' directives at the time, although he declined to provide evidence to support his statements. "Our group has no intention of providing information that is not in the public interest or that should not be disclosed by law or by decision of Justice."

However, legal expert Augustin Mpoyi points out that if a company wants to change the use of a logging concession, it must first return it to the State. The State can then re-allocate it as a conservation concession, but following the public consultation process described in the law.

Nyamugabo did not respond to email requests for comment from this media outlet.

Unpublished Audits

Ten days before the COP26 Climate Summit, where the DRC presented itself as a "country of solutions," President Felix Tshisekedi called for an audit of the DRC's forest concessions and the suspension of all "questionable contracts."

The first requirement of the €446 million agreement with CAFI was the publication, before the end of 2021, of an audit conducted the previous year by the country's Inspectorate General of Finance (IGF). The analysis focused on all concessions awarded or transferred since July 2014. The results have not yet been published.

In 2021, CAFI also commissioned an independent review of the legality of logging titles, led by a Spanish-Bulgarian consortium with funding from the European Union. EL PAÍS/Planeta Futuro's investigation gained access to an internal report from that consortium in which experts express frustration at the "lack of cooperation from Congolese public administrations at all levels." Environment officials and loggers argued that the EU team had no official authorization from the Ministry of Environment. And so it was.

"This casts doubt on the real willingness of the Forestry Administration to facilitate the review, despite being officially committed to…. [the agreement with CAFI] and being its main beneficiary," says this report from last June.

The government ended up signing the permit two months after the head of the EU delegation to the DRC requested it. And this is just one of several obstacles that have actively held up the review, pushing back its delivery date by nine months, to April 2022.

The review has been talked about since 2017, but the difficulty in accessing even the most basic information about the forest concessions means that conclusions about their legality remain elusive.

Conflicts of Interest

A four-year forest management initiative co-financed by the French Development Agency (AFD) and CAFI has also been delayed by administrative stumbling blocks in the DRC. In June 2021, French consultancy Forest Resources Management (FRM) was one of the companies shortlisted to provide technical support to the Ministry of Environment, which is responsible for implementing the program. One of the tasks of the chosen entity would be to create a method for independent Congolese observers to conduct their own audits of industrial concessions in the future.

However, FRM fell off the shortlist after an independent researcher specializing in the forestry sector in Central Africa warned of a conflict of interest. In a chain of emails sent to AFD and Congolese officials, and seen by this media outlet, it said, "FRM has long-standing commercial relationships with many of DRC's most notorious loggers; that includes two that, in 2018, accounted for 81% of total reported industrial timber production." One of these is the Norsudtimber group.

According to this researcher, the company appeared to have started recruitment for the program four months before the Ministry opened the tender. The job description was almost identical to the objectives of the AFD and CAFI-supported project, he noted.

The FRM did not respond to requests for comment from this media outlet. AFD said the program delays were due to "administrative requirements," adding that the process of hiring new consultants would conclude in March 2022.

Despite the obstacles to bringing illegal logging concessions to light, donors are also determined to review, by 2024, the new wave of conservation concessions, 27 in total. Of these, 21 are owned by logging-related investors seeking to diversify their portfolios.

Carbon Credit Trading

Fighting global warming allows investors to legitimately make money by caring for the climate and protecting some of the planet's most beautiful and vulnerable ecosystems. REDD+ projects in the DRC, for example, can profit by selling carbon credits to companies or individuals who want to offset their emissions by financing the conservation of Congolese forests. Each credit, known as a "verified carbon unit," corresponds to one metric ton of carbon dioxide emissions.

That is what the U.S. Blattner family has been doing in the DRC since it converted its logging concession in Isangi to a conservation title in 2009. Records show that the Isangi REDD+ project in the northern province of Tshopo has sold more than one million carbon credits to dozens of organizations around the world.

Among the entities that purchased Isangi credits are U.S. airline Delta Airlines, the City of Davos (Switzerland), British travel company Exodus Travels, Swedish logistics company Scanlog, and universities such as Marymount California University and the University of Tasmania. A part of the credits were sold for $15 (about 13 euros) through the Stand for Trees platform, supported by USAID, the U.S. international development agency.

The prices of the so-called "verified carbon units" sold by a project like Isangi's can be privately negotiated, so an observer cannot calculate how much an entity has earned by adding up the credits it has sold. In countries with weak governance, low technical capacity and widespread financial opacity, things become even more complicated.

The Big Question

When shown the transactions of the Isangi REDD+ Project, the former Tshopo Environment Coordinator until 2021, Félicien Malu, looks on in disbelief. "I had no idea they had been selling credits," he admits, although a project report highlights that project managers communicate frequently with him and other authorities. The administrator of the Isangi territory, Joseph Mimbenga, denies that they hold monthly consultations with him, as the document states: "It's false and untrue!" According to Mimbenga, the initiative assures him that it has never sold carbon credits.

Carbon credits belong to the Congolese state, and private operators must request authorization to sell them and report their transactions. The idea is that authorities and civil society organizations at all levels can monitor REDD+ projects in detail.

From the interviews conducted for this report, it is clear that no one person or institution in the DRC has an overview of who is selling what and what, if any, benefits they are getting. Even the country's Ministry of Finance inspectors are at a loss about the taxation of carbon projects.

So how do public bodies like the provinces, which lack the most basic knowledge and resources, know how much money they should be getting, and when, from REDD+ projects? "That's the big question," says national REDD+ coordinator Hassan Assani, whose own service used to operate from a prefabricated structure under a mango tree in Kinshasa. "At the moment, it largely depends on the goodwill of the projects."

This media outlet asked the owners of the Isangi REDD+ project how they report carbon credit sales. In email responses, executive director Brandon Blattner said they had submitted carbon credit transactions to the National REDD+ Registry in March 2020. But the DRC's National REDD+ Coordination claims to have no such data. "Our file on this project is empty," the agency confirms. "Perhaps they have spoken to other authorities."

The Isangi REDD+ project defends that they communicate with "government stakeholders" and meet with them at the provincial level. They do not provide further details. It added that it has not yet recorded annual net benefits and therefore has not triggered benefit sharing with the Executive, although it does claim to be complying with agreements with communities.

"I Call it the Wild West"

Upon taking office in April 2021, Environment Minister Ève Bazaïba pledged to crack down on corruption. She also announced her intention to create a regulatory authority for carbon markets to facilitate transparency and tax collection. The announcement by Bazaïba, known locally as "the Iron Lady," coincided with President Tshisekedi's call for a 20-fold increase in the price of carbon credits to protect the world's second largest tropical forest.

One year later, regulatory loopholes, weak governance and lack of transparency continue to leave a door open to potential abuses by political-administrative officials and investors, including through tax evasion.

"Opportunistic companies and public officials can easily take advantage of Congolese ignorance about carbon markets," argues a REDD+ expert at the Ministry of Finance, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals. "Carbon credits are different from timber: you can't see them being cut down and taken out of the forest. And, in any case, some people are untouchable."

Few investors have been working in the DRC for more years than those in the Blattner family. One of them is Elwyn Blattner, who prospered by buying land cheaply and acquiring bankrupt colonial businesses after Mobutu Sese Seko's rise to power in 1965, he told The New York Times in 1989. By the time he was 33, Elwyn already controlled more than 15 million hectares in the DRC, an area larger than Greece. "I call this the Wild West," he added, speaking unknowingly for future generations of investors in the country. "If you're willing to take a risk, there's an open horizon out there."

This research was conducted with the support of the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network.

Updated on March 23rd: After the publication of this story, the outlets were contacted by the Isangi REDD+ project owners, who said they meet with the Isangi Territory Administrator regularly. They also stated that they officially started the process with the National REDD+ Coordination body in March 2022.

- View this story on Mongabay