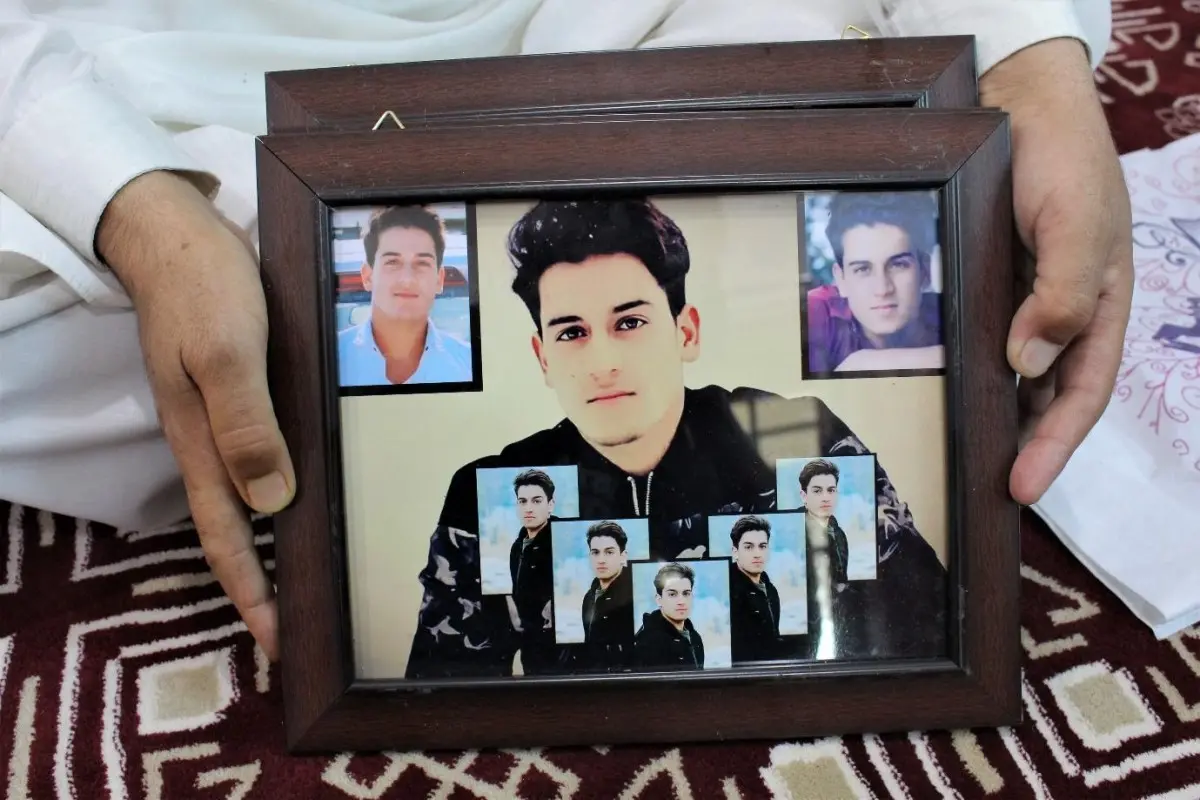

One sunny morning, we entered the modest home of Abdul Rashid Wani. Wani is a farmer from the Pulwama district in southern Kashmir. The wiry, middle-aged man directed us to his damp living room and began frantically puffing away at his jajeer (Kashmiri hookah). Then he began narrating the story of his son, Junaid Rashid.

A former college student, 20-year-old Rashid was killed in a gunfight with the armed forces last year in the neighbouring Shopian district. Around a month prior, Rashid had joined one of the many militant groups active in the conflict-ridden Kashmir region.

“Nobody knows why or how he joined the militants,” Wani told us, his eyes welling up while his wife, Rashid’s mother, silently brought in a tray of milk tea and biscuits. “Through appeals in the media, we tried our best to persuade him to return home,” he added. Soon after these appeals, Wani had received a phone call from government authorities informing him that his son had been killed and that his body would be buried in Handwara.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Located in northern Kashmir, Handwara is a day’s drive from Wani’s home. “I briefly saw Junaid’s body in a police station in Srinagar and thereafter, it was buried in Handwara,” Wani said, adding with a deep sigh that he himself had never mustered up the courage to visit his son’s grave.

Since April of last year, the government has stopped handing over the bodies of armed militants to their families and has, instead, been burying them in remote locations, citing COVID-19 concerns. In 2020, around 140 militants were buried in such locations, mostly in northern Kashmir. In 2021, the number of such burials crossed 100.

The funeral processions of these slain militants used to be observed in their native villages and towns; their bodies used to be interred in neighbourhood graveyards. However, as these funerals also drew in large crowds, the security establishment saw them as sites of radicalisation.

According to a 2018 study commissioned by the police department in Kashmir, half of all new militant recruits came from within a 10 kilometre radius of the residence of a killed militant. “It has been observed that, many a time, friends of killed militants manifest a tendency of pledging to join militancy on seeing the dead bodies and funerals of their friends,” the study, cited by the Indian Express, revealed.

In this context, being able to successfully put a stop to militant funerals has widely been seen as a strategic success. While citing COVID concerns, a top-ranking police official, in an interview, said that the burial of militants in isolated locations “stopped glamourising terrorists and avoided potential law and order problems,” calling the action “historic”.

According to another report by the Observer Research Foundation, an influential New Delhi thinktank, the funerals, which were occasionally attended by active militants, brought civilians in contact with them and “such an interaction is one of the first important steps in facilitating (militant) recruitment.”

At first glance, the home of one Mushtaq Ahmad Wani in Pulwama exhibits the affluence of content middle-class families; the ones who go on regular picnics, pay their children’s college tuition from their savings and gift them the latest smartphones. However, the death of Mushtaq’s 16-year-old son, Ather, has left his family full of questions.

Described as “hardcore associates of terrorists” in a police statement, Ather and two others were killed in December, 2020 after they threw a grenade at and fired upon a group of army soldiers. Ather’s family, however, disputes this account and maintains that he was only a schoolchild who had gone out with his friends. “I fail to understand how Ather, in the space of a few hours, was deemed a combatant when there was not even a single adverse police report lodged against him?” Mushtaq asked.

On the night of his death, Ather’s body was swiftly interred in Sonmarg in the presence of his father and uncle. Located in Northern Kashmir, Sonmarg, a hill station, is a five-hour-drive from Mushtaq’s home in Pulwama. “I was only able to see Ather’s face with a cell phone flashlight before lowering him into the grave,” Mushtaq remembered.

Even a year or so after Ather’s burial, Mushtaq is hopeful of interring his son’s remains at home, having already dug a grave for his son in their local graveyard. “Half of my soul is buried in Sonmarg,” Mushtaq lamented. “I am ready to bear all costs of exhuming Ather and burying him here.”

All the families that we talked to expressed concerns about the remoteness of these graveyards where the bodies are being buried.

“We have to borrow a car from our neighbour and spend an entire day to reach his grave,” said the father of Majid Iqbal Bhat, who was killed in a firefight with military in July. A native of the Shopian district, Bhat, a father of two toddlers, is buried more than 100 kilometres away in Handwara. “Especially in deep winters, because of the snow and shorter days, we are unable to travel to this remote graveyard,” Bhat’s father added.

Bhat’s mother, Naseema Bano, was distraught that her son was buried so far away. “One, of course, has to visit the grave even if we have to borrow money for the travel but I can still re-bury him in the local graveyard,” she said. “What if the remains of our sons are taken away at the middle of the night? We would not even know,” she added.

Travelling to these faraway districts also adds to the economic burdens of these families, some of whom said that they cannot afford private vehicles and the associated costs.

“If the government buries them locally, in the same district, it would be much more convenient for us,” said Shameema Akhtar, mother of Arshid Ahmad Dar, a 17-year-old militant who was killed in a gunfight last year.

Her voice sinking and desperately trying to hold back her grief, Akhtar told us that, before he joined the militants, Dar was the family’s only hope for a stable economic future. “My husband, Arshid’s father, cannot even do menial jobs because of a myriad of health issues. Recently, we could not even afford my daughter’s school fees, let alone travelling faraway frequently,” she said, as military jets whizzed above.

Many families also spoke of the meticulous surveillance they are subject to on their visits to these remote graveyards. “Our phones are confiscated before entering the graveyard and, sometimes, we are accompanied by police personnel,” Dar’s sister said.

The family of Rouf Ahmad Mir, a militant who was killed in Pulwama in August, 2020, also spoke about this graveyard surveillance. “The graves are numbered methodically and no insignias or epitaphs mark them,” said one of Mir’s family members.

After the government started (systematically) burying militants’ bodies far away from their hometowns, the militant groups also confiscated at least one body of an army soldier. Belonging to Shakir Manzoor, a 24-year-old rifleman in the Territorial Army division, was kidnapped by militants in August, 2020 while travelling in his car in the neighbouring Kulgam district. Shakir’s torn clothes were later found in an orchard nearby. In an audio clip released on social media – the veracity of which could not be independently verified – militants admitted to killing the young soldier and deliberately burying his body in secret.

After 13 months, Manzoor’s semi-decomposed body was recently found in Kulgam. “The entire village frantically searched for Shakir during these months,” Manzoor Ahmad Wagay, Shakir's father, told us as a constant stream of mourners poured into the family home.

“We dug through several kilometres of orchards and fields in search of Shakir,” Wagay, a farmer by profession, said. Revealing that he had even sought the help of pirs (faith healers) to locate his son’s remains, Manzoor said that he never had a doubt that Shakir’s body would be found. “My prayers were finally answered,” he added, while expressing a mix of grief and contentment. “We finally buried him in the ancestral graveyard.”

Siddiqa Ahmad and Aabida Ahmed are journalists based in India who have reported extensively in Indian-controlled Kashmir. They are using pseudonyms to protect their personal safety.